Why Economic Growth Isn’t Enough

Posted: May 12, 2010 Filed under: Columns, Economic Growth and Productivity, Taxes and Budget Leave a comment »Today’s budget problems aren’t America’s first. High debt levels accompanied our major wars, but they were quickly reduced soon after. “Deficits as far as the eye can see” in the mid-1980s were followed briefly by surpluses in the late 1990s. In all these cases, economic growth helped solve the problem. Today, that’s no longer possible.

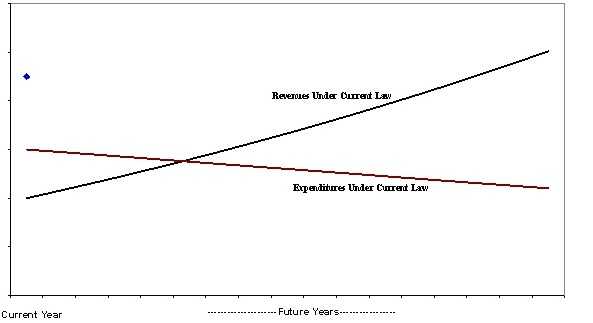

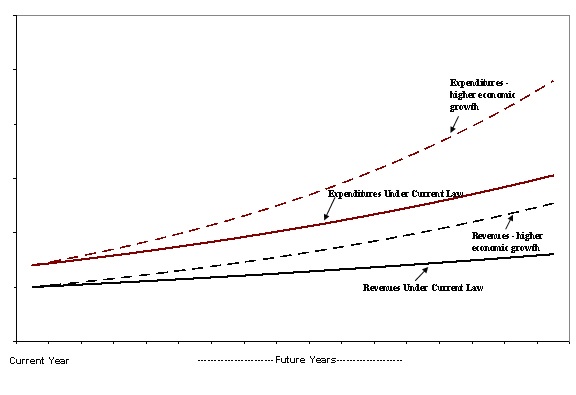

Failure to understand the causes of today’s historic impasse will stymie those budget reformers tempted to believe we can use the traditional pro-growth strategy to get our fiscal house in order. Most of history is on their side: in almost all past U.S. budgets—indeed, the budgets of most nations—revenues were scheduled to grow automatically along with the economy, and expenditures were scheduled to grow only if there was new legislation. Thus, revenues in some future year would always exceed that past expense, no matter how high any current deficit. But under the laws now dominating the budget, expenditures essentially are or will be growing faster than both revenues and the rest of the economy. In fact, we’re now locked into automatic expenditure hikes that will outstrip revenues under almost any conceivable rate of economic growth.

In the many budget policy reform discussions I’ve been part of, this disconnect from the past blocks understanding of our present fiscal situation. Thus, both liberals who want to maintain spending programs and conservatives seeking to keep taxes low seem to think—or, at least, want to think—that economic growth can once again solve our problems.

Just what is different now? Today, we are facing two fiscal problems, while before we had just one. In the past, fiscal imbalance was mainly a temporary, current issue only. Yes, Congresses would occasionally spend much more than they collected in taxes, sometimes heedlessly. But as long as revenues over time rose with economic growth and most spending was discretionary, push never came to shove as long as the next Congresses weren’t too profligate

In effect, during the nation’s first two centuries, all that was required to get the nation’s house in order was for future Congresses to limit new spending increases or tax cuts. Since future surpluses were always built into the established law at any one point in time, sound fiscal policy meant not turning those surpluses into unmanageably high deficits year after year.

Take the case of World War II, when our national debt ballooned. It’s usually cited as the great example of successful fiscal policy overcoming a depression. If in 1942 Congress had developed ten-year estimates of the deficit under “current law” on the books, the estimates would have shown massive surpluses. Spending was scheduled to drop dramatically in absolute terms and as a percentage of the economy or GDP once the war was over. Meanwhile, higher tax rates imposed to support war spending would stay in place until future Congresses saw fit to reduce them.

Jump ahead to today. Now, so much spending growth is built into law in permanent or mandatory programs that these programs essentially absorb all future revenues. Meanwhile, we’ve also cut taxes—widening the gap between available revenues and growing spending levels.

But why won’t even higher economic growth solve the problem? If spending growth were limited so it couldn’t exceed some fixed rate, then higher economic growth might increase the revenue growth rate enough to help restore balance. Unfortunately, spending growth is not set at a fixed rate. Instead, it generally is scheduled to grow faster when the economy grows faster.

Consider government retirement programs, such as Social Security. Most are wage indexed insofar as a 10 percent higher growth rate of wages doesn’t just raise taxes on those wages, it also raises the annual benefits of all future retirees by 10 percent. The same doesn’t hold for discretionary programs such as education, even though we might expect that teachers’ salaries would need to rise with economic growth. Instead, teachers’ raises must be appropriated every year. Meanwhile, in most retirement systems employees stop working at fixed ages, even though for decades Americans have been living longer. When spending rises with both wages and extra years of retirement benefits, extra economic growth just doesn’t provide much if any reprieve from fiscal imbalances.

Health care is a bit more complicated. Health costs tend to rise more than proportionately with incomes. If our incomes rise by 10 percent over the next few years, we tend to demand at least 10 percent more health care. With 20 percent income growth, we want even more than 20 percent increases in health goods and services. Of course, it’s not just a demand phenomenon. The higher economic growth may reflect improvements in health technology, along with its higher costs.

Today, so much of government spending is devoted to health and retirement programs that their growing costs tend to swamp gains we might achieve in holding down the ever-smaller portion of the budget devoted to discretionary spending. Some other programs add to the problem, since they, too, tend to grow with the economy: mortgage interest deductions as we demand more housing, subsidized pension contributions and other employee benefits as our wages go up.

Built-in automatic spending growth like I’ve just described means that balancing the budget today is far harder than simply putting the brakes on new tax cuts and spending increases. A do-little Congress can no longer save the day. Our elected officials are in a bind they hate: they must both say “No” to many new give-aways AND go back on unkeepable spending and tax promises made by past lawmakers…

The thumbnail version: seek economic growth, but don’t expect it to provide the budget slack it did when most spending was discretionary. Congress has already spent the revenues that economic growth will provide, so we need to weed our government’s garden as well as water it.

From Deficit to Surplus: How Budget Projections Used to Look under Current Law

How Budget Projections Look Today under Current Law: With and Without Additional Economic Growth