Growth in Income and Health Care Costs

Posted: June 4, 2013 Filed under: Columns, Economic Growth and Productivity, Health and Health Policy, Income and Wealth, Race, Ethnicity, and Gender 4 Comments »Worried about the stagnation of income among middle-income households? Or about the growth in health care costs? The two are not unrelated. In fact, middle-income families have witnessed far more growth than the change in their cash incomes suggest if we count the better health insurance most receive from employers or government. But is that all good news? Should ever-increasing shares of the income that Americans receive from government in retirement and other transfer payments go directly to hospitals and doctors as opposed to other needs of beneficiaries? Should workers receive ever-smaller shares of compensation in the form of cash?

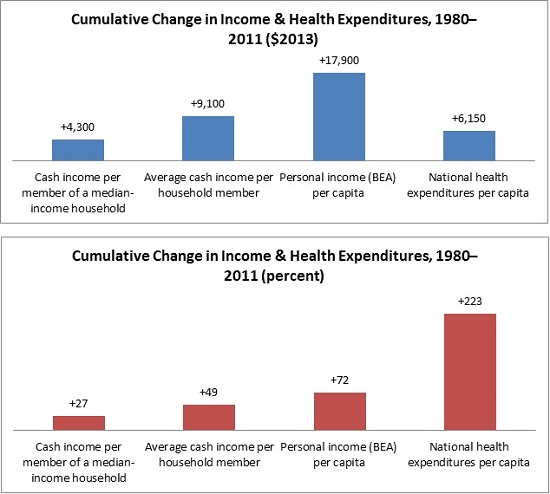

The stagnation of cash incomes in the middle of the income distribution now goes back over three decades. Consider the period from 1980 to 2011. Cash income per member of a median income household, which includes items like wages and interest and cash payments from government like Social Security, only grew by about $4,300 or 27 percent over that period, when adjusted for inflation. From 2000 to 2010, it was even negative. Yet according to data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis, per capita personal income—our most comprehensive measure of individual income—grew 72 percent from 1980 to 2011.

How do we reconcile these statistics? By disentangling the many pieces that go into each measure.

Growing income inequality certainly plays a big part in this story: much of the growth in either cash or total personal income was garnered by those with very high incomes. So the growth in average income, no matter how measured, is substantially higher than the growth for a typical or median person who shared much less than proportionately in those gains. But personal income also includes many items that simply don’t show up in the cash income measures. Among them is the provision of noncash government benefits, such as various forms of food assistance.

Health care plays no small role. In fact, real national health care expenditures per person grew by 223 percent or $6,150 from 1980 to 2011, much more than the growth in median cash income. If we assume that the median-income household member got about the average amount of health care and insurance, then we can see how little their increased cash income tells them or us about their higher standard of living.

Getting a bit more technical, there’s a danger of over-counting and under-counting health care costs here. Some of the median or typical person’s additional cash income went to extra health care expenses, so the additional amount he/she had left for all other purposes was even less than $4,300. However, individuals pay only a small share of their health care expenses; the vast majority is covered by government, employer, or other third-party payments. So, roughly speaking, typical or median individuals still got well more than half of their income growth in the form of health benefits.

The implications stretch well beyond middle-class stagnation. Employers face rising pressures to drop insurance so they can provide higher cash wages. For instance, providing a decent health insurance package to a family can be equivalent roughly to a doubling of employer costs for a worker paid minimum wage. The government, in turn, faces a different squeeze: as it allocates ever-larger shares of its social welfare budget for health care, it grants smaller shares to education, wage subsidies, child tax credits, and most other efforts. Additionally, the more expensive the health care the government provides to those who don’t work, the greater the incentives for them to retire earlier or remain unemployed.

In the end, the health care juggernaut leaves us with good news (that our incomes indeed are growing moderately faster than most headlines would have us believe) as well as bad news (that health care remains unmerciful in what it increasingly takes out of our budget).

In Bruce Bartlett’s last book (and his Economix article which pre-published his findings), he showed that if you include health care spending (which is tax subsidy supported) as public spending, the US is right in the middle of other OECD countries – although we spend less on family welfare and more on health. I suspect the only way around this is to allow employers to abandon third party coverage for employees and retirees and hire their own medical staffs and facilities directly – either as paid staff or as a feature in the facility in which they operate. While this won’t work for McDonalds, it will work for manufacturing and office work. Imagine if every building had a doctor employed as staff of either the employer or the building manager (as well as sick and well kids daycare). Sometimes demonetizing an activity is the best way to manage its costs – especially in a market, like health care, which tends toward monopoly pricing.

[…] Posted at The Government We Deserve on […]

[…] with higher incomes, we still pay a lot ourselves, only indirectly. In particular, we pay through lower cash wages when employers purchase health insurance, an important but often ignored aspect of the slow growth […]

[…] Posted at The Government We Deserve on […]