Opportunity for All Isn’t Gonna Happen on This Path

Posted: May 17, 2016 Filed under: Columns, Income and Wealth, Taxes and Budget 1 Comment »Over the past 30 or 35 years, income and government spending per household have both about doubled, but working- and middle-class Americans have seen much less improvement in their earnings, wealth, education, and skills than they did in earlier decades. The international economy and the concentration of power within the top 1 percent are major factors, but it’s hard to believe that we can’t do a lot better with the $60,000 in federal and state spending and tax subsidies we spend annually per household, or the $2 million in health, retirement, education, and other direct supports scheduled for each child born today. My recent study finds that the US budget is moving increasingly away from promoting opportunity for all.

At the same time, Hillary Clinton, Donald Trump, and almost everyone running for office ascribe to the notion of America as a land of opportunity while telling supporters they are being denied the opportunities owed them. But it takes more than rhetoric to climb out of our current political pit.

In the study I draw three major conclusions:

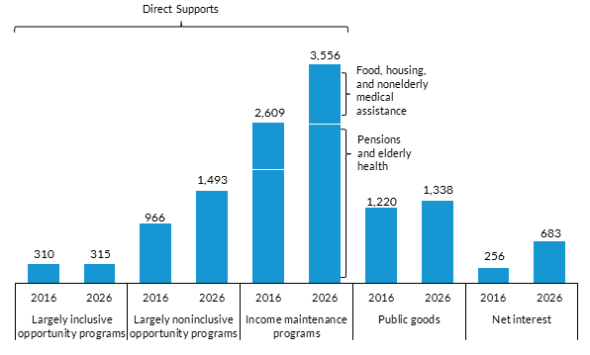

- First, the few programs that attempt to promote opportunity, such as work incentives and education, are scheduled to take a smaller share of available federal government resources. There is one major exception: large tax subsidies for housing and for employee benefits like retirement accounts continue to expand. However, by largely excluding low- to middle-income households, those programs show how today’s programs largely fail to promote opportunity for all. That is, they are not inclusive opportunity programs. Figure 1 summarizes these results.

- Second, if we wish to promote opportunity for all, we must carefully discern the outcomes pursued and judiciously measure how well programs achieve those outcomes. “Opportunity for all,” if left amorphous, lacks any prescriptive power, leads to claims that anything the government does or stops doing can promote opportunity, and, as long as the intended outcomes are unspecified, prevents assessing program performance. I suggest that opportunity for all is not simply an equity objective: it pursues outcomes centered on growth over time in earnings, employment, human and social capital, and wealth while it emphasizes inclusion, especially of low- and middle-income households. And I suggest that we can and should measure most programs by their performance on that opportunity standard, even if the primary standard by which they are judged—such as retirement, food security, or even defense—seems initially removed from that opportunity focus.

- Third, there’s tremendous budgetary potential for promoting opportunity whether the government increases or decreases relative to the economy. Realizing this potential doesn’t require moving backward on other fronts but shifting tracks, as from north to northeast, to also move forward on the opportunity front. The trick is to channel a larger share of the additional revenues provided by economic growth toward an opportunity agenda. Ten years from now annual federal spending and tax subsidies are scheduled to increase some $2 trillion (or roughly $15,000 per household), but essentially none of that growth goes to opportunity-for-all programs. Children receive almost nothing a decade hence, while interest on the debt rises significantly because we are unwilling to collect enough taxes to pay our bills as we go along.

When you look at these numbers, it seems clear that reorienting budget priorities could help provide opportunity in ways likely to promote equality in earnings and wealth. What is also clear, however, is that small ball is not going to get the job done when so much in the budget is moving in the direction of deform, not reform.

Figure 1

Total Outlays and Tax Expenditures for Major Budget Categories under Current Law

Billions of 2016 dollars

Source: Author’s tabulations of Congressional Budget Office data.

Notes: Public goods include such items as defense, infrastructure, and research and development that benefit the population broadly. Direct supports are programs and transfers that directly benefit households and communities, such as health care and education. Within direct supports, income maintenance programs such as Social Security, Medicare, and SNAP (formerly food stamps) protect a certain level of income and consumption, while opportunity programs aim to increase private earnings, wealth, and human capital over time. Largely inclusive opportunity programs benefit low- and middle-income groups, while noninclusive opportunity programs largely exclude them or provide them with fewer supports than upper-income groups.

Gene, Excellent article