Why Progressivity in Tax Policy Is Not A Simple Matter

Posted: November 16, 2021 Filed under: Uncategorized Comments Off on Why Progressivity in Tax Policy Is Not A Simple MatterPolicymakers and even policy analysts often consider the progressivity of specific proposals independently from the broader systems in which they operate. Consequently, they often leave the public with a misleading impression of how those proposals affect various income groups.

Here are four examples of how specific programs might appear to be regressive yet may not be when looked at more broadly:

Does making the child tax credit available to middle-income parents make it less progressive than if it benefits only low-income households?

Like the dependent exemption that preceded it, but was eliminated in 2017, the child tax credit (CTC) in part aims to provide government support for child rearing for all but the highest income households. The CTC recognizes that a family’s ability to pay tax declines as its size grows, almost no matter its income level. The earned income tax credit (EITC), on the other hand, has a very different goal. It aims to subsidize low-paid workers and it phases out at much lower income levels.

In isolation, increasing the more-targeted EITC looks more progressive than distributing the same additional dollars more widely through the CTC. Yet, the goal of legislators should center on the overall progressivity, efficiency, and fairness of the tax system, not each individual part. That includes distributing the total tax burden across families in a way that recognizes differences in their ability to pay, including the effects of family size. One can collect the same amount of tax from those, say, making more than $200,000 with or without a child credit by changing the relative distribution of taxes for households at that income level. Yet failure to adjust for family size would discriminate against households with children in favor of those without.

Was discouraging more low- and middle-income taxpayers from claiming the charitable deduction regressive?

By expanding a standard deduction that could be taken in lieu of itemized deductions, the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) discouraged most households from claiming the charitable deduction. After all, the standard deduction was more valuable for many families. Also, the higher standard deduction also benefitted lower-income families who didn’t itemize. Accordingly, those changes tended to be progressive, though by many measures the overall TCJA was not.

That doesn’t mean that limiting the charitable deduction to fewer than 10 percent of households represents good policy. Indeed, a charitable tax deduction for a small number of high-income households is politically unsustainable and discourages a more generous society. But, while it could be considered bad charitable and tax policy to limit a charitable deduction mainly to a few higher-income households, the way it was done was not necessarily regressive.

Should tax reform remove special exemptions for certain low-income people such as the elderly or the unemployed?

In its 1984 study leading to 1986 tax reform, Treasury urged Congress to repeal tax exemptions and deductions specifically for the elderly and the unemployed because they discriminated against other low-income households, including some who were worse off. Considered by themselves, these changes would have been regressive. Yet, Treasury and the Congress then targeted additional tax benefits to low-income families generally, thus adding to overall progressivity of the tax system.

Are state taxes regressive?

State taxes overall tend to impose higher average tax rates on lower income households than on those with higher incomes. Many state sales taxes, for instance, are assessed at a flat rate, while the consumption of taxed items comprise a much larger share of the income of lower-income households.

These taxes are regressive by a traditional measure that assesses whether the average rate of tax, or share of income paid in tax, falls—as income rises. But that can be misleading since it ignores the amount of tax people pay. Meanwhile, we often say spending is regressive if it grants larger amounts to those with higher incomes—for example, a larger educational grant for a higher-income student than for a low-income one would be considered regressive. But these are inconsistent measures, one looking at rates or shares and the other at amounts. One can’t determine the overall progressivity of a taxes and spending together when using inconsistent measures.

It turns out that much state spending such as funding for K-12 education tends to provide roughly equal benefits. And some programs, such as Medicaid, provide higher amounts of benefits to lower income families. Meanwhile, even the most regressive levy still usually requires higher income households to pay greater amounts of tax.

Thus, a measure of combined progressivity across tax and spending programs, defined by whether there is a net redistribution from those with more to those with less, suggests that higher taxes, even if regressive by the standard tax definition, typically create a progressive redistribution of income because of the additional spending they finance.

In sum, measuring progressivity one program at a time often misrepresents its full impact. It can lead to a variety of inefficiencies, as well as injustices among those who should be treated equally. Looking across multiple tax and spending programs almost always offers a superior way both to examine and design policy.

This column originally appeared on TaxVox on October 20, 2021.

How Existing Budgetary Commitments Could Affect President Biden’s Domestic Policy Goals

Posted: May 13, 2021 Filed under: Uncategorized Comments Off on How Existing Budgetary Commitments Could Affect President Biden’s Domestic Policy GoalsThe COVID-19 pandemic and accompanying recession laid bare many of the needs of working families and children, as well as federal, state, and local governments’ historic inattention to public health needs and preventative health care. In 2020, Congress responded by enacting approximately $3.5 trillion in economic relief bills. So far this year, it has approved another $1.9 trillion of relief through the American Rescue Plan. And President Biden has proposed two new initiatives that, combined, would cost roughly an additional $4 trillion.

Yet, all these efforts may still fail to achieve any long-term shift in the federal government’s domestic priorities. That’s partly because most of that relief was temporary, just as is much of 2021 spending either enacted or proposed.

To examine the potential long-term limits of these types of changes, our new report compares the budget projections in CBO’s February 2021 update, assuming a forthcoming end to the pandemic and recession, to its pre-pandemic January 2020 projections. While the February 2021 report does not include 2021 changes recently enacted or proposed, it does show the combination of the COVID-19 economy, low- and middle-income tax cuts (including economic relief payments), and significant new spending drove the federal budget deficit to more than $3 trillion in 2020, its highest level as a share of GDP since World War II.

In our report, we focus on inflation-adjusted (real) changes in revenues and spending in 2030 compared to 2019. Crucially, most of these changes were built into the law pre-pandemic and unchanged during the past year, so considering only new legislation would miss most of what is happening to the budget over time.

Most new revenues are driven by economic growth rather than legislated tax increases. Even in absence of any new legislated tax increases, CBO projects real revenues will rise by about 31 percent, or $1.067 trillion, in 2030, as compared to 2019, largely due to a growing economy. There is almost no difference between CBO’s pre- and post-pandemic projections for 2030 revenues.

Spending would increase by $1.424 trillion in 2030 relative to 2019 under the February 2021 projections, only slightly less than the increase CBO projected in January 2020. Most of this substantial spending growth, such as the automatic increases in annual Social Security benefits, was locked in years ago. By allowing most spending growth to occur automatically, today’s Congress passively cedes much of the power of the purse to past Congresses.

Spending growth is focused on retirement benefits and health care. Again, excluding new 2021 legislation but including the 2020 pandemic spending, more than one-third of total growth in annual spending in 2030 as compared to 2019 would be due to Social Security. Medicare would absorb about 32 percent, higher interest on the debt, 13 percent, and Medicaid and other health care subsidies, 12 percent.

By comparison, other spending growth would be relatively modest, declining substantially in relative importance. For example, other mandatory spending would decline by about $9 billion in real terms, while nondefense discretionary spending would increase by $93 billion. Defense spending during this period would rise by roughly $48 billion.

Overall Social Security, health, and interest on the debt would comprise 90 percent of the total growth in spending and about 120 percent of the revenue growth, again a very similar percentage to what was predicted pre-pandemic.

We will include 2021 legislation in further analysis when more data on the president’s latest proposals are available. One factor likely will become far more important in that analysis: While interest rates fell enough in 2020 to offset an increase in projected interest costs that usually accompanies deficit increases, the financial markets are starting to project higher long-term interest rates. So new additions to debt likely will show up more readily in higher interest costs.

Much of the new spending proposed by President Biden in his American Jobs Plan and American Family Plan is less targeted to the pandemic and more to longer-term needs of working families and children. Still, much is proposed only for a few years, with revenue increases stretched out over longer periods of time.

Even if Congress enacts these changes, President Biden’s inability so far to address the rising unfunded increases in retirement and health costs, along with higher interest costs, leave him still facing huge headwinds pushing back against any significant and permanent shift in priorities.

This column originally appeared on TaxVox on May 13, 2021.

Could Better Government Have Lowered Pandemic Deaths by 100,000 or Reduced Costs by a Trillion Dollars?

Posted: March 1, 2021 Filed under: Uncategorized Comments Off on Could Better Government Have Lowered Pandemic Deaths by 100,000 or Reduced Costs by a Trillion Dollars?It never is easy for government to respond to crises, especially one as big and far-reaching as the COVID-19 pandemic. Yet, a better policymaking process might have saved tens of thousands of lives and massive amounts of money.

While the media focus on big political fights, the key to policy success—especially in a crisis—is having a process where expertise, and not politics, drives the first draft of options for solution.

Who, then, should our elected officials place in charge of that first draft? To start, they should be people highly trained in how to address the problem at hand. In the Executive Branch, ideally public health issues surrounding a pandemic would be managed by career staff at the Centers for Disease Control or the Food & Drug Administration, while staff at the Treasury Department or the Office of Management and Budget would respond to the economic fallout.

In Congress, legislative options would be developed first by its nonpartisan staffs in offices such as the Government Accountability Office, the Joint Committee on Taxation, or the Congressional Budget Office, though some committees unfortunately lack separate nonpartisan staff and would need to turn more immediately to Democratic and Republican committee staff. Besides subject matter expertise, these staffers should apply their knowledge in an objective, analytical fashion, saving the political compromises for lawmakers themselves.

One complication is the increased blurring of boundaries between politics and expertise. Many political appointees in agencies and on congressional staffs are expected to support a political party or boss rather than to provide objective analysis. Meanwhile, almost all civil servants are trained to perform disinterested analysis but must “stay in their lane.” Thus, they usually are not allowed, asked or even organized to design options, much less those that cut across policy realms, such as health and the economy. Those limitations often force the best of them to leave. in absence of broader organizational reform, therefore, how to organize for the next emergency will continue to be constrained more than necessary. Regardless, no organizational structure is perfect; the most crucial first step is to find the right people to work on that first draft.

Don’t get me wrong. Experts should not usurp the role of elected officials, who must take those options and balance them against legitimate—and often contradictory—concerns. But starting out on the right foot significantly increases the probability of success.

Elected officials, in turn, should maintain their proper roles of defining broad objectives, assessing what is politically feasible, and making final decisions. But they should not usurp roles for which they are inadequately trained any more than they should run the labs attempting to come up with new vaccines.

Pity the poor civil servants, layered deep in government behind thousands of political appointees in the Executive Branch and Congress, who know how to make life marginally better for the nation. They have vital information, but it just can’t navigate the political and bureaucratic maze.

The system’s failure helps explain while, more than a year after the onset of the pandemic, we still struggle with inadequate availability of tests, limited vaccine production, a struggling vaccine distribution process, uncoordinated research on drug treatments, and an ongoing failure to provide everyone with the best possible masks. Maybe better decisions would have reduced deaths only by 4 percent in each of these areas, but added together, that’s 100,000 lives as of late February.

The same process failure plays out in the design of our big pandemic relief bills. As usual, Congress is battling over a top-line number: Should the current measure total $1.9 trillion as proposed by President Biden or some smaller amount. Yet, too little attention is given to how to spend that money most efficiently.

Many ideas for better targeting relief to those who most need it and to spur a faster economic recovery are out there, such as those that highlight direct purchases over simple transfer payments, especially transfers likely to be saved, or making use of pandemic relief with higher multiplier effects. But Congress largely is ignoring them.

In sum, had policymakers focused on effective first drafts of options to address the current pandemic, they might easily have saved 100,000 lives and $1 trillion. Process reforms may sound boring, but without them we will face another round of policy failures when the next crisis comes along.

This column originally appeared on TaxVox on March 1, 2021.

How Much Has the Pandemic Affected President-elect Biden’s Opportunity to Chart a New Course?

Posted: January 26, 2021 Filed under: Uncategorized Comments Off on How Much Has the Pandemic Affected President-elect Biden’s Opportunity to Chart a New Course?Largely as a consequence of the pandemic, trillions of dollars have been flowing out of the Treasury’s coffers. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects the federal budget deficit for 2020 alone will exceed $3 trillion, three times higher than pre-pandemic estimates. Meanwhile, President-elect Joe Biden has suggested that trillions of dollars more should be spent to deal with the pandemic and then to address many of the nation’s social needs that will continue to exist beyond the current economic slowdown.

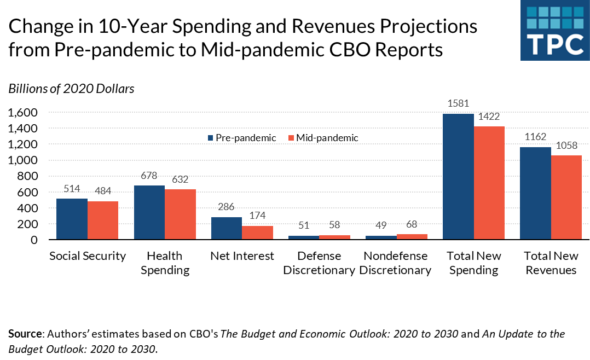

To determine how the longer-term budgetary effects of the pandemic have been playing out so far, and how similar pandemic-related expenditures might also affect the long-term direction of government spending, we compare the CBO’s September 2020, mid-pandemic, projections of real dollar changes in 2030 versus 2019 under current law to what CBO projected pre-pandemic in January 2020.

For the most part, we see fairly modest differences in budget forecasts of where increases in future spending would occur. Almost all of the pandemic-related boosts in spending are temporary, and the long-term trends remain dominated by the growth patterns that Congress and previous presidents had already built into the law, not by long-term societal needs and inequities highlighted by the pandemic.

The one exception is for interest costs. They still rise significantly under the September 2020 projections, but by about $100 billion less than in January 2020, largely reflecting CBO’s forecast of a lower interest rate environment due to Federal Reserve policy and the effect on saving and investment of a world-wide economic slowdown.

Comparing the mid-pandemic to the pre-pandemic forecast, lower interest rates would more than offset the additional interest costs associated with higher levels of debt, resulting in overall lower federal debt service as late as 2030. To be clear, lower interest costs due to a world-wide slump and slower projected economic growth are not good news.

Until recently, a growing economy would provide enough revenue to give a president significant leeway to chart new paths for spending. Such opportunity will likely elude President-elect Biden, however. When 2030 is compared to 2019, Social Security, health, and interest on the debt alone are projected to comprise 91 percent of the total real spending growth of about $1.4 trillion.

These three sources of additional costs would absorb 122 percent of the total revenue growth of about $1.1 trillion, assuming current law would remain unchanged after September 2020. Already this 122 percent figure is an understatement of what is likely to occur over the coming decade, as the new, largely temporary COVID-19 relief adopted in late December, along with the relief likely to be enacted in early 2021, will add to longer-term interest costs, assuming rates don’t fall further. Moreover, President-elect Biden made campaign promises to increase taxes only for those with very high incomes. That implies that, unlike CBO’s measure of current law, he could feel compelled to accept a lower “current law” revenue base by extending the middle-class individual income tax cuts included in the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) that are scheduled to expire after 2025.

Under January pre-pandemic projections, Social Security, health, and interest on the debt would constitute a very similar 94 percent of the total growth in spending and 127 of the total growth in revenues.

Although annual deficits by 2030 are large and growing, they remain close to the pre-pandemic projections. Of course, the accumulated debt will be much larger than formerly predicted. Thus, so far, the long-term impact of the pandemic and the nation’s responses to it reinforce and accelerate pre-existing budgetary trends, both in terms of overall spending projections and ever-larger gap between revenue and those expenditures.

President-elect Biden’s first priority will be to address the pandemic and the short-term economy, thus further increasing government spending. The open question: Once the pandemic is controlled, how will Congress and the incoming President adjust long-term spending and tax policy? Higher debt levels alone may make it harder for the President to shift the nation’s fiscal path. Yet, absent significant reductions in the built-in growth rates in health and retirement programs, a substantial increase in revenues, or both, our current fiscal trajectory will increasingly hamstring the nation’s ability to address other priorities.

This column originally appeared on TaxVox on January 19, 2021.

My Simple New Year’s Wish for 2021: Less Nastiness

Posted: January 19, 2021 Filed under: Uncategorized Comments Off on My Simple New Year’s Wish for 2021: Less NastinessAt New Year’s I usually try to pass on a note of hope that goes beyond the policy issues I usually address. This year I’ve had a lot of trouble coming up with a message, watching as a rising tide of nastiness has been sucking the life out of the very soul of our nation. The attack on the Capitol represents a culmination of President Trump’s attempt to weaponize nastiness; hopefully, it’s also the nadir of the dysfunctional government we’ve come to expect. But, as one of my wise friends, Frances Michalkewitz explained, a culture of nastiness has been expanding for some time now. The challenge for us is what can we do about it. I don’t have all or even most of the answers, but here are some thoughts.

You might think that I pose an unfair challenge. Like children growing up in the same family with an abusive father, we can easily divide into two camps: those who seek to appease and become more dependent on the abuser, and those who live in continual anger at both him and those who live in denial of what he has wrought. Both approaches threaten to take us further down dark alleys and extenuate the pain. Our psychological health and that of those around us requires more: an ability to turn outward, avoid letting the negativity eat away at us, follow a moral compass, and strengthen our bonds with other parts of humanity. That, indeed, may be unfair, but it’s the best opportunity we have to deal with whatever grievance we feel.

We certainly can stop voting for nasty people. If we can’t be independent and switch political parties, at least punish the nasty people in the primaries. I’ve been amazed over my career at how much individuals, even when they switch jobs, location, or family, largely behave as they did before. We can’t let those who have shown themselves to be nasty sway us with their campaign promises; we must also look to their records and how they have acted toward others in the past.

While voting is a way to change the political dynamic, it often requires limited effort. To further make an impact, we also must try to tend with cultural forces that aren’t amenable to government regulation.

We can spend less time with media that uses nastiness or promotes a sense of superiority among its audience as a way to entertain us, boost ratings, and garner attention or profits. While there is no doubt that modern media plays a vital role in expanding the culture of nastiness, we are the ones who provide the incentives for it to be that way. When we spend more time watching nasty people or reading their Twitter feeds, whether with their real or fake personalities (as on reality TV), we effectively pay for them entertain us with their nastiness. Let’s take away their paychecks or, for some, the positive reinforcement that fuels their nasty and often nihilistic behavior.

Language needs attention as well. Whenever we make any claim about any group, whether Black or White, Republican or Democrat, male or female, police or social worker, we tend to speak in generalizations. It’s an unavoidable limitation of language that we generalize to simplify and summarize, but no one in any group is average, so that adjectives or summary conclusions applied to a group are almost certainly incorrect for some members of that group. That resentment follows shouldn’t be surprising. This is a much larger subject; the point here is to recognize how any generalization will be received by its members.

As Gabby Giffords recently explained, there’s no magic recovery in store for us as a nation. Of course, fight for justice. But much of our power, particularly over culture, lies within what we do, not what we try to force others to do. We need to remember what our parents and grandparents taught us about seeking, as Lincoln so eloquently expressed it, the better angels of our nature. Random acts of kindness, more donations to charity, welcoming for everyone, getting to know and befriend those different from us, and challenging ourselves to learn new things. When it comes to culture, the good more displaces than defeats the bad.

Less nastiness. That’s my New Year’s resolution for myself and my hope for you. Let’s win this battle.

Congress Could Fix the ACA’s Individual Mandate Without Waiting for the Supreme Court

Posted: December 18, 2020 Filed under: Uncategorized Comments Off on Congress Could Fix the ACA’s Individual Mandate Without Waiting for the Supreme CourtIn the coming months, the US Supreme Court will rule for the third time on the constitutionality of the individual mandate that is a central element to the 2010 Affordable Care Act (ACA). This case was brought by several Republican state attorneys general, who argued that because Congress effectively eliminated the tax-based mandate, the entire law is an unconstitutional intrusion into states’ rights.

Yet every party to this conflict—the Court, Republicans, and Democrats—has twisted itself into knots by failing to understand how a modest penalty for not obtaining insurance can adhere to both Republican support for individual responsibility and Democratic efforts to expand health insurance without violating the Constitution. Congress easily could clear this up by changing the nature of the tax penalty.

Keep in mind that the ACA’s mandate was never a true mandate but rather a modest tax on those who choose to not get insurance. When the ACA was enacted, the penalty tax, or fee, was equal to 2.5 percent of household income up to a maximum of $695 per adult. In the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), Congress set the penalty tax to zero.

Long before the ACA, I suggested that the simplest way to enforce a mandate is to make some federal tax benefit—say, a higher standard deduction, separate or enhanced Child Tax Credit—dependent upon having health insurance. Or, in contrast to a $695 penalty on those without health insurance, simply adding a $695 deduction for those with health insurance.

Paul Van de Water of the Center for Budget and Policy Priorities and I outlined the administrative benefits of this idea here. Since eligibility for almost every government tax benefit already is based on taxpayers engaging in certain behavior, such a step likely would make the debate over when a mandate is a tax, a tax a mandate, and at what rate does one convert into the other, disappear.

Instead, the political system has tied itself into knots over the current mandate. The Court gets further into metaphysics, Republicans indirectly argue for larger government, and Democrats fail to pursue a simple legislative solution that could expand health coverage.

Let’s start with the Court. You may remember that Chief Justice Roberts opined in 2011 that Congress could not force people to purchase health insurance but could tax those who fail to do so.

When Congress set the individual mandate penalty rate at zero as part of the TCJA, it eliminated the requirement in practice, but it did not repeal the ACA, or even the tax. The Court now must decide whether a zero-rate mandate is no longer a tax but still an unconstitutional mandate. This will test whether the Court wants to engage in a debate more metaphysical than the type Roberts accused economists of, such as the lack of distinction between a tax and a mandate. During oral arguments earlier this month Roberts seemed to decline, telling lawyers for the states that want the law reversed that it is “not our job” to legislate repeal of the Act.

The semantic, legal distinction between taxes and mandates never made much sense. Our Constitution clearly allows Congress to tax all of us to fund benefits for only some of us. What is the logic of saying that Congress can impose an income tax to pay for, say, low-income housing assistance or farm subsidies for a relative few, but can’t use a tax to encourage people to obtain insurance?

For their part, the attorneys general who want the ACA thrown out effectively have been arguing for bigger government. When it comes to health care costs, either we pay ourselves or someone else pays for us. Thus, if Republicans gut incentives for people to insure themselves, they encourage the substitute—more government subsidies and regulation.

When you take into account Medicare, Medicaid, tax subsidies, and insurance for government employees, government already covers about 65 percent of total healthcare costs. The desire for more individual responsibility was a key reason why Mitt Romney, then the Republican governor of Massachusetts, first enacted a mandate as part of his insurance reform.

A mandate also is important if government is going to require insurance companies to sell to all comers, with no underwriting for pre-existing health conditions. Without some government-imposed nudge, many people would not insure themselves until they got sick, increasing the burden on providers and government and raising insurance premiums to unsustainable levels. Indeed, Republicans have already raised the cost of ACA exchange subsidies since, by gutting the mandate, they encourage more healthy people not to purchase insurance until they get sick.

Regardless of these efficiency issues, it’s simply unfair when people who buy insurance have to cover the costs of those who have equal ability to purchase insurance, but do not.

Let’s not let Democrats off the hook. They were unwilling to tie insurance coverage to other government benefits because they didn’t like the appearance, even if the claw back of net benefits led to exactly the same result as the penalty they imposed.

Instead of wallowing in this pointless debate over taxes versus mandates, policymakers should be focusing on the real health issues facing the nation. Legislators could make the Supreme Court case forever moot by adopting a practical solution consistent with both conservative and progressive principles. Because ACA reform has been proposed by President-elect Biden, this issue could come before Congress soon. Despite all the ruckus over the mandate, this is actually an area where Republicans could find common ground with Democrats.

This column originally appeared on TaxVox on December 14, 2020.

What Trump’s Tax Returns Reveal About Wealth Inequality And Slower Economic Growth

Posted: October 20, 2020 Filed under: Uncategorized Comments Off on What Trump’s Tax Returns Reveal About Wealth Inequality And Slower Economic GrowthThe New York Times account of President Trump’s tax returns reveal far more than his personal ability to avoid taxes. They show how the tax law can make it easy for the very wealthy to avoid taxation. And they reveal more than deficiencies in the tax law. Bankruptcy laws allow wealthy investors to shift losses to others even while they retain gains elsewhere, bank lending practices favor the rich, and for the last three decades monetary has subsidized highly-leveraged wealthy investors by driving borrowing costs ever lower and creating a huge wealth bubble that has saved even the most inefficient of investors.

Whether the president engaged in questionable or even illegal tax practices is only a small part of this story. But by focusing on his personal behavior, Congress may miss an opportunity to address the broader issues of fairness and equity and economic growth. Poor tax and economic policy can spur inefficient investment and concentrate opportunity on too few people.

One way the very rich avoid tax is through the discretionary nature of the individual income tax for investors. That is, the income from appreciated property (capital gains income) is not included in taxable income until the underlying asset is sold, a discretionary step taken by the investor. In the early 1980s I calculated that less than one-third of the net income from capital showed up on tax returns. Studies comparing income declared on individual income tax returns with wealth reported in estate tax returns implied that taxpayers reported a rate of return often hovering around 2 percent, when the value of stocks and other assets rose by an average of around 10 percent per year. Close to one-third of wealthy people in each of the years examined declared a return on their income tax returns of less than 1 percent on their wealth.

While owners of corporations often do indirectly pay corporate income tax, large real estate investors typically use pass-through business and have long been close to exempt from both corporate and individual taxation. In the heyday of the tax shelter era of the 1980s, when real estate investors were making money while shielding other income with huge losses, members of the Senate Finance Committee wondered aloud whether Treasury would collect more revenue if the tax law simply exempted the investments from tax.

Further, if property is held until death, no income tax ever is owed on any accrued but unrealized gains.

Meanwhile, while gains can be deferred or excluded from tax at death, property owners can immediately deduct almost all expenses on their tax returns.

Interest costs are among the most important of those deductible costs, and the nominal interest costs written off are often a multiple of the real costs of borrowing. For example, if annual inflation is 2 percent and annual borrowing costs are 4 percent, the taxpayer deducts twice the real expense of the borrowing. The most highly leveraged investors receive the most benefits.

Investors in real estate can also take advantage of “like-kind” exchanges that allow them to swap real estate properties with another owner and defer the recognition of any capital gains income from the investment.

In this “Heads-I-Win, Tails-You-Lose” world, owners can declare bankruptcy of one company that is performing poorly while maintaining ownership of others that may be thriving. Earn $5 million on an investment in one company, lose $6 million in another; declare company bankruptcy in the second case, and the owner can come out ahead, while others bear the cost.

Bank lending practices, such as the Deutsch Bank loans to Trump, provide a third source of protection. Employees and officers of large financial institutions can make big money even for bad investments. They can earn promotions and bonuses by boosting the institution’s cash flow, at least until everything blows up. And, of course, those bonuses and promotions usually can’t be recaptured.

Finally, by creating real interest rates on short term debt that are close to zero, monetary policy can make the real cost of borrowing also close to zero or even negative after the taxpayer deducts nominal interest costs in excess or real interest payments. As one result, the ratio of household wealth to income rose remarkably from the early 1990s to today, generating at least an additional $25 trillion of nominal wealth over and above a normal growth rate. Recent efforts by the Federal Reserve to buy up all sorts of debt to keep the financial system functioning has further protected wealthholders even in the midst of the current COVID-19 crisis.

Taken together, all these policies have contributed significantly to increases in wealth inequality while they protected even the most inefficient investors. Trump’s tax returns may be just the tip of the iceberg, only one piece of visible evidence on a set of economic policies that may continue to lead to years of sluggish growth.

This column originally appeared on TaxVox on October 19, 2020.

COVID-19-Related Policies Can Better Boost the Economy By Targeting Less To Savers

Posted: June 12, 2020 Filed under: Uncategorized Comments Off on COVID-19-Related Policies Can Better Boost the Economy By Targeting Less To SaversCongress has responded to the COVID-19 pandemic-induced economic slowdown by putting hundreds of billions of dollars directly into people’s pockets. Much of this came from the Economic Stimulus Payments ($1,200 per adult/$500 per child) administered by the IRS and expanded unemployment benefits. The evidence so far suggests that many households are saving much of that money, along with higher shares of their private income. And that suggests those payments are having weaker economic benefits than they otherwise could.

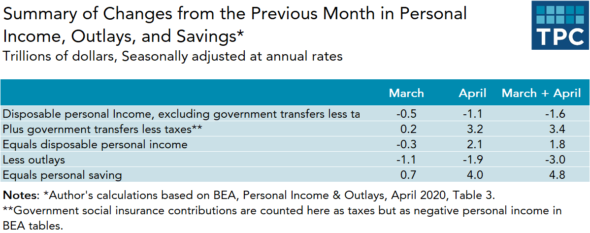

A recent report by the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), found that the saving rate of US households rose from about 8 percent in pre-pandemic February to 13 percent in March to 33 percent in April. Annualized, that would be equal to $4.7 trillion in increased savings, far more than the increase in net transfers made so far by government through the various COVID-19 relief bills.

Before taking into account changes in government transfers, disposable personal income (net of taxes and related social insurance contributions) fell across March and April by about $1.6 trillion (all numbers here are at a seasonally adjusted annual rate, so that, roughly speaking, a $100 billion decline in one month, if permanent over the year, would add up to an annual decline of $1.2 trillion). Thanks largely to delaying the income tax filing deadline from April 15 and those COVID-19 relief bills, government transfers less taxes rose by about $3.4 trillion over those two months. Despite the devastating losses in wage and other income suffered by millions, disposable personal income overall rose by about 13 percent or about $1.8 trillion (on an annual basis). Still, outlays (basically all forms of personal spending) fell at an annual rate of about $3 trillion, or nearly double the $1.6 trillion decline in disposable personal income before those net transfers.

There are many reasons why people were not spending in the pandemic months of March and April. At first, in March, people were afraid to travel, shop, or eat out. Then governments closed many businesses and imposed stay-at-home orders, leaving people without places to spend, and often without jobs. Those abnormal pressures weakened the normal recession-fighting ability of fiscal and monetary policy to boost consumer demand.

Even in a classical economic downturn, recovery often takes time simply because people become extra cautious with whatever money they have. Yale economist and Nobel laureate Robert Shiller recently noted how the tendency of some people to embrace austerity may have extended the length of the Great Depression. When people spend less, they save more, and with less spending on goods and services, the demand for workers to produce those goods and services falls as well.

Admittedly, the BEA numbers, which only cover income and items such as checks or refunds paid by the end of April, tell a very incomplete story. The stimulus funds delivered by rebate payments or unemployment benefits no doubt lessened the severity of the downturn. Many households did or eventually will spend their rebate payments and increased unemployment and other benefits, though for some it may take a while. Without a continuation of these transfers, the declines in personal income will soon exceed the net increase in transfers provided by government. The jury, therefore, is still out on just how well these recent congressional actions will stabilize the economy in the short term and stimulate demand over the medium term.

Still, the data raise important policy questions. My colleague Howard Gleckman has questioned the value of government distributing payments to almost everyone, not just those who are most in need. As he notes, many types of consumer spending (e.g., travel, entertainment) are just not available at the current time.

Low-income households and the unemployed probably will spend funds quickly, if for no other reason than to pay for rent, food, and utility bills. Many people, however, suffered little or no decrease in income and have reduced their consumption for reasons other than immediate financial shortfalls. Even after months pass, they are unlikely to take two cruises at the end of the year to make up for the one they gave up this spring. These households may simply deposit those government payments and save them for the longer-term.

Congress should study both the successes and failures of the early government payments to boost demand as it considers the next round. It needs to carefully consider how well each dollar of spending or tax reduction meets the two primary objectives of the day: caring for those who are hurting and stimulating the economy.

Here are four rules that should guide these deliberations:

- Government purchases likely stimulate the economy more than many forms of transfers and tax reductions;

- Almost any speed-up of test and vaccine production and delivery leads to faster economic recovery;

- Reinforcing a normal tendency for consumption rates to rise as income and wealth falls, government spending on households whose incomes have declined and whose bills are due will be more effective than providing windfalls for those who have not lost income and already are saving more than usual; and

- Not every cause, no matter how worthy for other purposes, deserves equal attention as a response to our current health and economic crises.

Using these four guideposts can ensure the effectiveness, efficiency, and equity of future federal responses to the current health and economic crisis.

This column originally appeared on TaxVox on June 8, 2020.