Millennials: Today’s Underserved, Tomorrow’s Social Security and Medicare Bi-millionaires?

Posted: September 16, 2015 Filed under: Aging, Columns, Health and Health Policy, Income and Wealth 2 Comments »When America’s Social Security system was first established in 1935, the public was deeply concerned about the fate of our elderly, who were then on average poorer than the rest of the population, less capable of working, more likely to work in physically demanding jobs, and less likely to live close to two decades past age 65. Today’s concept of Social Security was actually only one part of an act aimed at meeting the needs of the poor, old, needy, and unemployed of all ages.

In the early decades through the 1960s, Congress expanded old-age supports largely to cover important gaps such as spouses and survivors, disability, health insurance and inflationary erosion of benefits. Today, however, Social Security grows based on past laws that preordain increases in old-age support, largely independent of how the needs of the elderly and nonelderly have evolved or will evolve.

In a newly released study, Caleb Quakenbush and I find that a typical couple retiring today is scheduled to receive about $1 million in cash and health benefits; many millennials will receive $2 million or more. In effect, we’ve now scheduled many young adults to be future Social Security and Medicare bi-millionaires. And the growth continues; the succeeding generation, born early in the 21st century and sometimes referred to as the homeland generation or generation Z, is scheduled for significantly higher benefits. Add to these amounts additional Medicaid expenditures that also go to many elderly if in a nursing home for any extended period of time. (These figures are “discounted”—that is, they show what amount would be required in a saving account, at age 65, earning real interest, to provide an equivalent level of support.)

In fact, a very high proportion of all growth in federal government spending over the next several decades is currently scheduled for Social Security and Medicare. Almost all other spending, whether for children or defense, infrastructure, or the basic functions of government, already is held constant or in decline in absolute terms, and sometimes in a tailspin relative to the size of the economy and the federal government. Only other forms of health care and retirement support, interest costs, and tax subsidies are on the rise.

Such developments are hardly sustainable. Simple math tells us that they will continue to impose costs that the millennials and younger generations are already experiencing: cuts in other benefits for them and their children, higher taxes, and reduced government services when they are in school, working, or middle-aged.

Next time you read a headline on growth in student debt, the falling real value of the child credit, declines in federal spending on education and infrastructure support, or fewer soldiers and sailors, keep in mind that these stories all follow as a consequence of where past Congresses have directed almost all government growth. Of course, governments almost always spend more as an economy and the tax base expand, whether the size of government relative to the economy grows, stays constant, or declines. But past governments traditionally allowed future legislators and voters to choose what to do with those additional revenues; they weren’t stuck with leaving that decision to prior legislators.

How did we get here? As Congresses and presidents added to Social Security over the years, it became more generous. Health insurance was expanded to cover hospitals and doctors, then more recently under President George W. Bush, drug benefits. Cash benefits were raised through various enactments under Republican and Democratic presidents alike.

One big culprit is the retirement age, which, by remaining stable on the basis of chronological age, does not remain stable on the basis of years of support, which increase as people live longer. A typical couple retiring at the earliest retirement age now receives benefits for close to three decades, which is roughly the expected lifespan of the longer living of the two. Spend $25,000 (discounted) per year on each person, but then do it for 20 years or so per person, and you come up with a figure like $1 million for a couple.

Since the 1970s, real annual benefits have also been growing automatically as wages rise. In fact, the combination of “wage indexing” and failure to adjust for life expectancy schedules Social Security to rise forever faster than the economy.

Then, of course, there are the health care costs. People are getting more years of medical support as they live longer. Plus, the federal government has never effectively tackled the increasing costs that result almost inevitably in a system where you and I can bargain with our doctors over whatever everybody else should pay to support our next procedure or drug.

By the way, none of these calculations account for the decline in the birth rate and its effect on the number of workers available to support such benefit growth. Roughly speaking, the taxes available to support any system decline by about one-third when the ratio of workers to retirees falls from 3:1 to 2:1.

We’ve traveled a long distance from 1935’s legislation and its goal of addressing the needs of people of all ages.

Reforming Disability Policy: Tough Choices Required

Posted: August 14, 2015 Filed under: Columns, Income and Wealth, Taxes and Budget Leave a comment »Setting disability policy is tough. Very tough. It’s tough empirically to measure and distinguish among degrees of disability or need. It’s tough legally and administratively to draw boundaries without excluding some sympathetic person or giving an inappropriate level of benefits to someone whose needs can’t fully be assessed. It’s tough economically to transfer resources to people with disabilities without setting up perverse incentives that separate them from the workplace and their fellow workers. It’s tough socially because the needs are so great.

Disability policy has gotten increased attention recently because the Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) trust fund is unable to pay our current benefits through 2016. But reform should involve more than money. By defining eligibility for benefits partly by the inability to work, SSDI and other federal disability policies effectively discourage recipients from trying to support themselves. If they work, they lose their benefits. This needs to be fixed. But how?

In a recent conference sponsored by the McCrery-Pomeroy SSDI Solutions Initiative (disclosure: I helped organize the initiative and still serve as advisor), no one advocated reducing benefits to bring SSDI back into balance. Nor did anyone suggest merely raising taxes.

Most speakers talked about the need to modernize US disability policy—in particular, to offer opportunities for people who want to work, can work at some level, or can keep working if they receive help when they first develop a health problem or impairment. Speakers recognized that work is therapeutic and that disability policy should account for the factors that can affect someone’s disability differentially across his or her lifetime, such as the episodic nature of many mental illnesses and the kinds of rehabilitation that can prove helpful to different people at different times.

Disability policy is exactly the same as other policy in one respect: it contains a fairly precise, even if implicit, calculus of what and whom will and won’t be funded. So, any reform to the policy must address the balance sheet.

The President and Congress seem ready to punt on dealing with SSDI, effectively covering shortfalls by transferring money from Social Security Old Age Insurance (OAI). Despite the pretense, such a move is not costless. Today’s taxpayers and beneficiaries won’t need to pay for the growing costs of SSDI, but future taxpayers and beneficiaries—of SSDI or other federal programs—will inherit even higher SSDI or OAI deficits, along with their compounding interest costs. Meanwhile, today’s catalyst for reform is neutralized.

As I listened to the McCrery-Pomeroy conference speakers propose adding work incentives and supports to SSDI (a suggestion I lean favorably toward, despite many design issues), it struck me that the proponents were implicitly suggesting that there is a better way to spend the next SSDI dollars than simply expanding the current program. If those proponents genuinely believe that work incentives and supports are the right way to direct additional dollars, then they also imply that we ought to look at how Congress already has scheduled additional dollars to be spent.

Some advocates may try to claim that we shouldn’t make such marginal budget comparisons. When I co-wrote a book on programs for children with disabilities, my fellow authors and I were criticized in one review for noting simply that the principle of progressivity requires figuring out who needs support the most. Such a critique ignores that we have to make choices, so we may as well do them as best we can. No one, proponent or opponent of current or any reformed law, can get around the simple fact that dollars spent one way cannot be spent another.

Let me put this in terms of the politics. Politicians never want to identify losers because then we voters crucify them. They want to operate on the give-away side of the budget: spending increases and tax cuts. So how can we give politicians some protection to reform disability policy if you and I know that putting relatively more money into work supports changes the nature of SSDI and prevents some other use of the money?

Here’s one way: emphasize the long-term dynamic that reform in a growing economy makes possible. Counting everything from health care to education to disability policy, our social welfare budget now spends about $35,000 annually per household. As the economy grows over time, the number is going to increase—perhaps to $70,000 if the economy doubles in another few decades. We don’t need to cut back on disability programs absolutely in order to allocate a share of those new marginal dollars to different approaches. We simply need to focus the growth of those future budgets.

SSDI and OASI grow automatically over time because benefits are indexed for real growth in the economy over and above inflation. No legislator determines that today’s additional expenditures should be directed one way or another; it’s in a formula set decades ago. Why not consider reducing that automatic growth to finance more subsidies and supports for people who want to keep working? What about capping growth—at least for those getting maximum benefits? What about re-allocating some of the federal health budget, where so many of the dollars are captured by providers rather than consumers, to help pay for work supports?

Or what about cutting back on those features of SSDI that add to the anti-work incentives? For example, what about paring the ability to increase your benefits by about 30 percent if you retire at age 62 on disability insurance instead of old age insurance, at least for people at higher incomes? Or at least not increasing that disability insurance bump, as now happens automatically when the full retirement age increases?

We can shift toward a more modern disability insurance system, but only when we face up honestly to the trade-offs implicit or explicit in every system. We will never move disability policy away from its antiwork emphasis if we’re not willing simultaneously to address the way we put additional resources into the current prevailing system. And, as best I see it, that is just what a scared Congress and president are about to do.

Combined Tax Rates and Creating a 21st Century Social Welfare Budget

Posted: June 26, 2015 Filed under: Children, Columns, Income and Wealth, Taxes and Budget 1 Comment »In testimony yesterday before a joint hearing of two House subcommittees, I urged Congress to modernize the nation’s social welfare programs to focus on early childhood, quality teachers, more effective work subsidies, and improved neighborhoods. One way lawmakers can shift their gaze is by considering the effects of combined marginal tax rates that often rise steeply as people increase their income and lose their eligibility for benefits.

While some talk about how we live in an age of austerity, we are in fact in a period of extraordinary opportunity. On a per-household basis, our income is higher than before the Great Recession and 60 percent higher than when Ronald Reagan was elected President in 1980.

A forward-looking social welfare budget should not be defined by the needs of a society from decades past. Two examples of how our priorities have shifted: Republicans and Democrats didn’t always agree on the merits of Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) or the Earned Income Tax Credit, yet they agreed on the need to shift from welfare to wage subsidies. Ditto for moving from public housing toward housing vouchers.

I sense that both the American public and its elected representatives are united in wanting to create a 21st century social welfare budget. That budget, I believe, should and will place greater focus on opportunity, mobility, work, and investment in human, real, and financial capital.

However, for the most part, our focus has been elsewhere. As I show in my recent book Dead Men Ruling, we live at a time when our elected officials are trapped by the promises of their predecessors. New agendas mean reneging on past promises. Even modest economic growth provides new opportunities, but the nation operates on a budget constrained by choices made by dead and retired elected officials who continue to rule.

For instance, the Congressional Budget Office and others project government will increase spending and tax subsidies by more than $1 trillion annually by 2025, yet they already absorb more than all future additional revenues—the traditional source of flexibility in budget making.

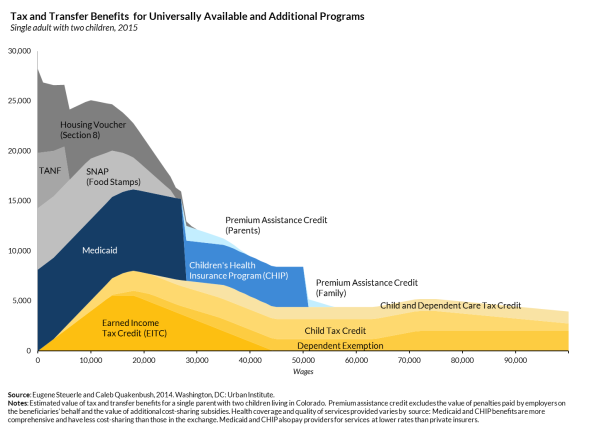

I am concerned about the potential negative effects of these programs on work, wealth accumulation, and marriage of combined marginal tax rate imposed mainly on lower-income households. To see how multiple programs combine to reduce the reward to work and marriage, look at this graph.

For households with children, combined marginal tax rates from direct taxes and the phasing out of benefits from universally available programs like EITC, SNAP, and government-subsidized health insurance average about 60 percent as they move from about $15,000 to $55,000 of income. This is what happens when a head of household moves toward full-time work, takes a second job, or marries another worker.

Beneficiaries of additional housing and welfare support face marginal rates that average closer to 75 percent. Add out of pocket costs for transportation, consumption taxes, and child care, and the gains from work fall even more. Sometimes there are no gains at all.

While there is widespread disagreement on the size of these disincentive effects on work and marriage, there is little doubt that they exist. One solution: Focus future resources on increasing opportunity for young households. Make combined tax rates more explicit and make work a stronger requirement for receiving some benefits.

This post originally appeared on TaxVox.

Assessing “Wrongs,” Mainly on the Young, to Pay for “Rights”

Posted: March 26, 2015 Filed under: Aging, Columns, Income and Wealth, Taxes and Budget Leave a comment »What happens when the claim to some financial right from the government creates some financial “wrong” somewhere else?

That is, when the government’s balance sheets don’t balance, and there aren’t enough assets to pay for claims on them, someone must get short-changed. If that “someone” must accept unequal treatment under the law, has the right been matched by a “wrong?” These issues have now arisen for underfunded state pension plans, but they continue to apply in other arenas, such as the unequal assessment of property taxes in states like California. In these and other cases, the young often end up paying the piper.

Protecting rights has long been crucial to maintaining a democratic order. The United States has a long history of protecting citizens’ rights, embedded from the beginning of the nation in the Bill of Rights and, since then, in many legal and constitutional clauses. These aim largely to establish liberty and require equal treatment under the law. When it comes more narrowly to most disputes over private property and assets, there are no “unfunded” government promises; contestants simply dispute over who gets the private funds. The court effectively fills out the balance sheet when it resolves those private disputes. A higher inheritance to one party out of a known amount of estate assets, for example, means a lower amount for another. There’s no third party or unidentified taxpayer who must to contribute or add to the estate so all potential inheritors can walk away happy.

When it comes to financial “rights” established by law, the issue becomes more complicated. The latest cases getting much attention revolve around the rights of state and local public employees to the benefits promised by their pension plans, even when those plans do not have the assets to cover the claims. Some courts have determined that the promised benefits are inviolable under state constitutions, regardless of available assets; other courts have recently interpreted state laws differently, led by the bankruptcy and financial distress of state pension plans.

As another example, some states give longer-term homeowners rights to lower taxation rates than newer homeowners. Proposition 13 of the California Constitution requires that property taxes cannot be increased by more than a certain rate, effectively granting existing homeowners lower tax rates than new homeowners receiving the same services for their tax dollars.

So where does the money come from? Saying that it can be the future taxpayer still dodges the issue of whether the allocation of benefits and costs meets a standard of equal justice.

Thus, when people lay claim to nonexistent government assets, “rights” can’t be totally separated from the “accounting” system under which they are assessed. I’m not a lawyer, but I believe courts and legislators do not do their job completely if they don’t admit to and address the following questions in any disputes on such matters:

- How can we judge anyone’s right to some financial compensation, pension benefit, or lower tax rate without at least knowing where and how the balance sheet is or might be filled out?

- How does the claim to a right by one set of citizens affect the rights of other citizens?

Even when courts determine that any resulting injustice is constitutional or the prerogative of the legislature, they still should do their balance-sheet homework.

In some arenas, the courts have made clear that the lack of underlying funds limits the rights of people to some promised benefit. The United States Supreme Court has stated, for instance, that Social Security benefits can be changed regardless of past legislative promises. This system is largely pay-as-you-go: benefits for the elderly come almost entirely from the taxes of the nonelderly. Because promised cash benefits now increasingly exceed taxes scheduled to be collected, even the pay-as-you-go balance sheet has not been filled out: some past Congress promised that benefits would grow over time without figuring out who would pay for that growth. Legislators can rebalance those sheets constitutionally without violating the rights of a current or future beneficiary. Whether they do so fairly is another matter.

When the courts have leaned toward treating as unalterable the rights of some citizens to unfunded promises made in the past, however, they have directly or indirectly required some unequal treatment under the law, with the young often paying the piper.

Our Urban Institute study of pension reforms in many states reveals that efforts to protect existing but not new state pensions almost always requires the young to receive significantly lower rates of total compensation than older workers doing the same work. Worse yet, we have determined that to cover unfunded liabilities from the past, some states are adopting pension plans that grant NEGATIVE employer pension or retirement plan benefits to new workers, essentially by requiring them to contribute more to the plan than most can expect to get back in future benefits.

In the case of California’s limited property tax increases, new, younger homeowners are required to pay much higher taxes than wealthier, older, and longer-term homeowners.

In these cases, it seems fairly clear that the “rights” of existing state workers or homeowners leads to an assessment of “wrongs”—unequal taxation of unequal pay for equal work—on others, mainly the young, to fill out the balance sheets.

As I say, I’m not a lawyer, but I do know that 2 + 2 does not equal 3. When the courts say that you are entitled to $2 and I’m entitled to $2, they can eventually defy the laws of mathematics if only $3 is available. It’s not that the declining availability of pension benefits to many workers and rapidly rising taxes are problems to be ignored. It’s just that assessing wrongs or liabilities on unrelated parties to a dispute is unlikely to represent equal justice under the law or an efficient way to resolve public finance issues.

Addressing income inequality first requires knowing what we’re measuring

Posted: February 18, 2015 Filed under: Columns, Economic Growth and Productivity, Income and Wealth, Taxes and Budget 1 Comment »Politicians, researchers, and the media have given a good deal of attention recently to widening income inequality. Yet very few have paid attention to how—and how well—we measure income. Different measures of income show very different results on whether and how much inequality has risen. Without clarity, even honest and non-ideological public and private efforts to address inequality will fall short of their mark—and, in some cases, exacerbate inequality further.

How we typically measure income

Income measures tell different stories about opportunity and can be useful for different purposes. Some studies on income inequality measure income before government transfers and taxes—for instance, studies that compare workers’ earnings over time. Studies of the distribution of wealth or capital income, too, typically exclude any entitlement to government benefits. These “market” measures capture how much individuals have gained or lost in their returns from work and saving.

More comprehensive measures examine income after transfers and taxes. Transfers include Social Security, SNAP (formerly food stamps), cash welfare, and the earned income tax credit. Taxes include income and Social Security taxes. These measures best capture individuals’ net income and what living standards they can maintain, but not their financial independence or how much they are sharing directly in the rewards of the market.

Within both sets of measures (pre-tax, pre-transfer and post-tax, post-transfer), most studies still exclude a great deal. Health care often fails to be counted, even though increases in real health costs and benefits now take up about one-third of all per-capita income growth. Most of these health benefits come from government health plans (like Medicare and Medicaid) or employer-provided health insurance. Households pay directly for only a minor share of health costs, so they often don’t think about improved health care as a source of income growth.

How improving our definition of income—and using alternative measures—sharpens our view of income inequality

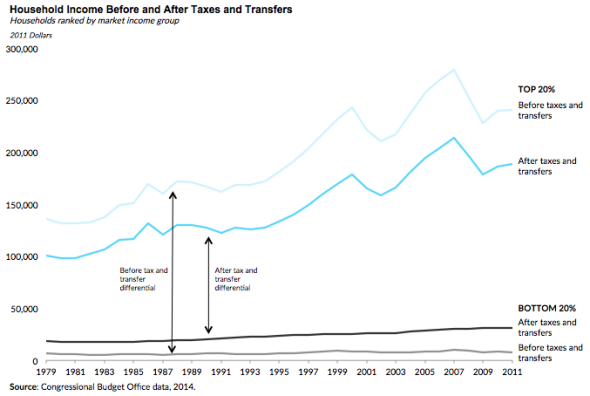

Starting with a more comprehensive measure of income, and then breaking out components, can improve our understanding of income inequality and its sources. As an example, let’s use some recent Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates, which provide perhaps the most comprehensive measure of household market incomes (consisting of labor, business, capital, and retirement income), then add the value of government transfers and subtract the value of federal taxes.

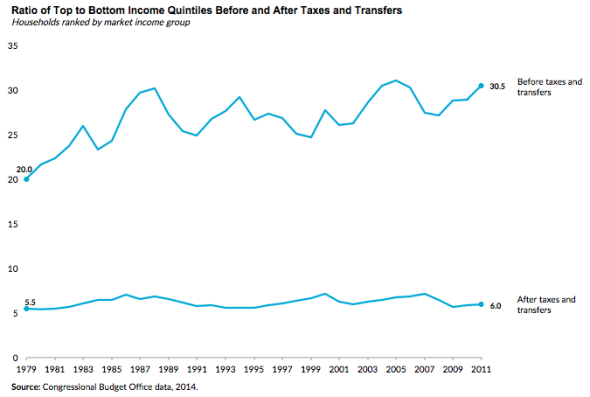

Between 1979 and 2011, the average market incomes—that is, incomes before taxes and transfers—of the richest 20 percent of the population (or the top income quintile) grew from 20 times to 30 times the incomes of the poorest 20 percent (the bottom income quintile).

When examining income after taxes and transfers, however, the relationship between the top and bottom income quintiles is more stable. It starts at a ratio of about 5.5:1 in 1979 and increases very slightly to 6:1 by 2011.

We find somewhat similar trends when comparing the fourth quintile with the second quintile. After taxes and transfers, income ratios don’t change much over this period, though the market-based measures of income show increased inequality. Of course, the very top 1 percent still has gained significantly; in 2011 it had nearly 33 times the income of the bottom 20 percent, compared with about 19 times in 1979.

What’s still missing

Even the CBO measures, however, are far from comprehensive. They exclude many benefits that are harder to measure or distribute, such as the returns from homeownership and the value of public goods like highways, parks, and fire protection. As Steve Rose points out, even more elusive are the broadly shared gains in living standards brought by improved technology and new inventions.

Why getting it right matters

Though defining income may seem like merely a technical exercise, it has huge consequences. Inequality has always been a political football: all sides tend to quote statistics that support their policy stances while ignoring the statistics refuting them. Yet if we want good policy, we’ve got to be open to how well any particular policy might improve income equality by one measure or make it worse by another, often at the same time. This is not a new story: bad or misleading information almost inevitably leads to bad policy.

This column first appeared on MetroTrends.

America’s Can-Do New Year’s Resolution

Posted: January 6, 2015 Filed under: Columns, Economic Growth and Productivity, Income and Wealth Leave a comment »How about a national new year’s resolution for 2015? Here’s my suggestion: let’s resolve to restore our can-do spirit, sense of destiny, and vision of frontiers as challenges rather than barriers. Let’s remember that fear and pessimism multiply the negative impact of bad events, whereas optimism reinforces positive outcomes. Think of Louis Howe, who added “the only thing we have to fear is fear itself” to Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s first inaugural address, or Henry David Thoreau, who wrote that “nothing is so much to be feared as fear.”

Now, seven years after the start of the Great Recession, it’s a good time to reflect on just how lucky we are as a nation and on the vast ocean of possibilities that lie before us. If we don’t see those possibilities, we’ve simply turned our back to them—and forgotten how America became America in the first place. In Dead Men Ruling, I attack viciously both the notion that we live in a time of austerity and the politics that sells pessimism as a way of clutching onto our piece of the national pie.

No one knows the future, of course. But the evidence points strongly toward the potential of a people whose can-do spirit helped it establish the first and now longest-lasting modern democracy, conquer frontiers of land and space alike, enhance freedom at home and abroad, and lead in the industrial, technological, and information revolutions.

Though income tracks only some of our general gains in well-being, we’re hardly poor. Our GDP per household is about $145,000, and real income per person is more than 75 percent higher than when Ronald Reagan was first elected president. We are richer than before the Great Recession. And, even projections of slower growth imply that average household income will rise by around $24,000 within roughly a decade.

We have available goods and services of which kings and queens of old could not have dreamt: not just the very visible gains in ways of communicating and entertaining ourselves, but fresh fruit and vegetables year round, life expectancies and health care far beyond those of our parents and grandparents, and continually improving automobiles, shelter, clothing, travel options, plumbing, and building architecture. And much more to come.

Of course, it’s part of our human condition to focus on the next problems, the ones we haven’t solved. Such striving provides the very basis for continued growth. Your hard labors, your dedication and sacrifices, and your everyday efforts to care for older and younger living generations may not make news. But they do make the world go around.

Our mistake comes from paying attention to those in politics, the media, or our own community who turn our mutual problems into excuses for personal attacks or a sense of helplessness rather than calls for further joint and individual efforts. We know the temptations: for the media, if it bleeds, it leads; for the politician, if it smells, it sells; for the business, if it deceives, it succeeds. But there’s no reason that either they or we need fall prey to such tricks.

If some current debates aren’t as enlightened as they might be, we can still sense progress from where they might have been a generation ago. We don’t debate whether cops should discriminate against different groups—an issue my brother-in-law confronted while working for the FBI in Little Rock, Arkansas in 1957—but instead how to pay proper respect to each person, civilian and cop alike. We don’t debate whether people should have enough food to eat but whether graduate students should collect food stamps. We don’t debate whether to help the disabled but how to extend efforts toward the mentally ill, the autistic, and those who are too old to be treated in school settings. We don’t debate whether to protect the old but whether our old age programs emphasize too much middle-age retirement rather than the needs of the old. When we engage these debates, whether on the same or different sides, most of us concentrate on how to do better, how much government efforts help or hinder progress, and how to shift our resources toward more effective or productive efforts.

In the end, the case for progress rests not on some wild-eyed dream but on the simple notion that we stand on the backs of those who went before us. Available knowledge expands. It doesn’t recede—even if at times we let our minds recede through laziness, prejudice, and fear of the new, or we reinforce political institutions that protect their power or status by blocking advancement.

That’s where we Americans are especially lucky. The can-do spirit, the entrepreneurial urge, and the freedom to try new things have been among the greatest strengths of our people, who continually find new paths forward and ever-broader vistas.

So my optimism is easy to explain: I trust in you. Happy New Year.

If I Care About Economic Mobility, Should I Vote for MIT or… MIT?

Posted: September 3, 2014 Filed under: Columns, Income and Wealth Leave a comment »I’m pleased that politicians from both sides of the aisle are focusing on economic mobility. In life, the deck gets stacked fairly early and connections play a big role. In an open and democratic society like the United States, it’s not so much that a person can’t get a hit; it’s that one person steps up to the plate with three balls and no strikes, and the next with no balls and two strikes. The odds that the second person ends up with a higher batting average than the first after 10 times at bat is just about nil.

One reminder of how connections and early stacking of the deck reinforce each other came in the mail a few days ago: a chance to cast my vote for the officers of the American Economic Association (AEA). I’m supposed to select five people from nine candidates. The list shows some diversity along lines now somewhat demanded by society—that is, three women and one person of color. But, seven of the nine—and all six white males—have a connection with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, or MIT (five PhDs and two faculty), so I have to vote for three MIT-connected economists at a minimum. Harvard lost its usual spot; only five of the nine have a major connection, including three with bachelor’s degrees from there. In fact, only one of the nine does not have a Harvard or MIT connection—though she has taught at Princeton, which usually gets at least token representation in this annual vote.

I know many of these candidates and have great respect for them. But I doubt that most of them believe fully in the hierarchical system from which they are now beneficiaries.

A number of years ago I had two colleagues who had done all but dissertations (ABDs) in history at the University of Virginia, ranked as one of the better schools in the country for that subject. Both were told by an adviser it wasn’t worth the trouble to write their dissertations. Jobs teaching college history and requiring a PhD, they learned, were so rare that they were already doomed: they were from too low-ranked a high-ranked university.

The financial industry has an extensive old boy (and occasionally old girl) network with the Ivy League. One of my daughters went to Princeton; though a biology major, she was recruited to join Wall Street (she didn’t accept). A former research assistant I knew got an MBA from the University of Texas at Austin when it became well-known for its rigor. Despite doing quite well, he later complained that without the Ivy League connection he couldn’t even get interviews with Wall Street firms.

Richard Perez-Pena recently penned a piece for the New York Times detailing the lack of progress among elite colleges in enrolling low-income students (not yet a standard along which politically correct diversification levels are expected). For instance, studies out of the University of Michigan and Georgetown University find that at 82 schools rated most competitive by a Barrons profile, only 14 percent of the student population comes from the poorer half of the nation’s households.

Look at top appointees under this president and former ones. Many come from a very few colleges— particularly the ones with which the presidents are connected (Obama loves Harvard; his predecessor, Yale), or have parents who owned banks, or other crucial connections. Even in sports, which is relatively competitive, think of the quarterbacks (RGIII) or golfers (Tiger Woods) who got a start even before age 10 learning from a parent or other close contact. And do you really think that all the current Hollywood stars with famous actresses or actors as parents just came out of genetically superior material?

I could go on, and I’m sure there is not a reader among you who couldn’t expand the list. In fairness, I should add some of my own early and lucky links, such as attending St. Xavier in Louisville, KY, perhaps the top high school in the state, where my family had gone for generations.

Researchers today work long and hard at trying to figure out which policies could help create a more mobile society, one where of starting at the bottom still left decent odds of making it to the top, or where success didn’t get defined so intensely by early connections or the track on which one started. So far we haven’t been very successful, though there are clearly some government steps that can be made, such as creating more equal access to subsidies for saving. But much is still determined by how we organize ourselves socially outside of government and just what we expect from our institutions. And, in truth, a thriving society should want successful parents to teach their kids all that they can, so simplistic leveling policies can easily start to threaten both their freedom and the wider societal growth that their successful kids can generate.

Still, I think it clear that many of the ways we select and discriminate hurt our society and hinder many from achieving their potential. So do I vote for MIT, or for MIT, or not at all?

Why Delayed Social Security Reform Costs Us

Posted: July 29, 2014 Filed under: Aging, Children, Columns, Income and Wealth, Taxes and Budget 1 Comment »This morning, I testified before the House Ways and Means subcommittee on Social Security. Below is a lightly edited transcript of my spoken remarks. A full copy of my written testimony can be found here.

Contrary to the popular argument that we live in an age of austerity, we live in an age of extraordinary opportunity. Yet, as I argue in a new book, Dead Men Ruling, we block progress by refighting yesterday’s battles and trying to control too much an uncertain future. As one reflection, in 2009 every dollar of revenue had been committed before that Congress walked in the doors of the Capitol.

Looking to Social Security, after three quarters of a century of continual growth, it has largely succeeded in providing basic protections to most, though not all, older people. Now, as psychologist Laura Carstensen at the Stanford Center on Longevity suggests, we should be redesigning our institutions around the new possibilities that improved healthcare, reduced physical demands, and long lives provide. But the eternal automatic growth of Social Security is not conditioned on any assessment of society’s opportunities or needs. Not making best use of the talents of people of all ages. Not child poverty or educational failures or the incidence of Alzheimer’s or autism.

Let me focus on three problems caused by this past, rather than future, focus:

Unequal Justice

Social Security redistributes in many ways, both progressive and regressive. And in many ways, it fails to provide equal justice.

Among the most outrageous, working single parents, often abandoned mothers, are forced to pay for spousal and survivor benefits they cannot receive, often receiving at least $100,000 fewer lifetime benefits than some who don’t work, pay less Social Security tax, and raise no children.

Similarly, the system discriminates against two-earner couples, spouses who divorce before ten years of marriage, long-term workers, and those who beget or bear children before age 40.

Middle Age Retirement

People today retire for about a decade longer than they did when Social Security first started paying benefits. The biggest winners of this multi-decade policy have been people like the witnesses at this table and members of Congress, who, if married, now get at least $300,000 in additional lifetime benefits.

But there are other consequences: a decline in employment, the rate of growth of GDP and personal income, as well as lower Social Security benefits for the truly old.

Meanwhile, within a couple of decades, close to one-third of the adult population will be on Social Security for one-third or more of their adult lives. There is no financial system, public or private, that can provide so many years of retirement for such a large share of the population without severe repercussions for individuals’ well-being in retirement and the workers upon whose backs the system relies.

The Impact on the Young

Today, lifetime Social Security and Medicare benefits approximate $1 million for a couple with average incomes throughout their working lives, Rising by about $18,000 a year, benefits for a couple in 2030 a couple are scheduled to grow to about $1 1/3 million.

Meanwhile, the rate of return on contributions falls continually for each generation. Each year of delayed reform shifts more burdens to younger generations from older ones, with the largest impact on groups like blacks and Hispanics, in part because they comprise a larger share of those future generations with lower returns.

Summary

In summary, each year of delay in reforming Social Security:

- Continues a pattern of unequal justice under the law;

- Threatens the well-being of the truly old;

- Increases the share of benefits paid to the middle aged;

- Leads government to spend ever less on education and other investments;

- Contributes to higher nonemployment, lower personal income and revenues; and

- Increases the burden that is shifted to the young and to people of color.