Governing After Over-Promising

Posted: October 18, 2012 Filed under: Aging, Columns, Health and Health Policy, Taxes and Budget 4 Comments »For almost anyone following closely our presidential candidates’ statements, it is absolutely clear that each pledges more than he can deliver. As a result, we must vote for the candidate who can better govern after over-promising.

Consider especially the big three items driving upward the budget deficits: growth in health costs, growth in retirement costs, and the tax cuts that keep passing our bills and related interest costs onto future generations. One simply can’t balance the long-term budget without dealing with these three. Yet both Obama and Romney remain largely silent about what we might have to give up in these arenas for years to come.

Social Security reform? “We can easily tweak the Social Security program while protecting current beneficiaries, ensuring that it’s there for future generations,” President Obama says. “[I am not] proposing any changes for any current retirees or near retirees, either to Social Security or Medicare,” Governor Romney proclaimed at the first presidential debate.

Medicare? The president fights to retain long-run hopes for “well over $1 trillion” in cost savings that he thinks are in Obamacare. But the Congressional Budget Office says that Obamacare raises health costs overall and that any long-run savings are just that, long-run, as well as uncertain. Romney would replace Obamacare and restore additional Medicare-directed spending. CBO numbers say that simply abandoning Obamacare would add to the deficit since the bill also includes tax increases and other measures that more than offset the health cost increases.

As for premium support or vouchers versus traditional Medicare, the candidates do engage in a debate, but generally over changes that would be phased in at some time long distant from when they need to tackle the deficit. Taxes? Romney proclaims that his reform would reduce revenues or at best be revenue neutral: “We are not going to have high-income people pay less of the tax burden than they pay today. […] I do want to bring taxes down for middle-income people.” He would also cut tax rates by 20 percent and “keep revenue up by limiting deductions and exemptions,” or perhaps he would do less, if those limits don’t supply enough revenues. Obama, in turn, holds with his promise from the last campaign for no tax increases for anyone making less than $250,000. Analysis after analysis shows that keeping this promise would entail only modest progress on the deficit.

Discretionary spending? Although not one of the big three drivers of our budgetary problems, both candidates would pare it dramatically as a share of GDP, but their campaigns only emphasize what they would protect. Obama would invest in education, and Romney now likes Pell grants, though he would give Big Bird some liposuction. Romney says he would somehow maintain a higher defense budget than Obama.

These candidates are not the first to try to tell us how much they will do for us or at least how they will absolve us—particularly the woe begotten middle class—from sharing in any future budgetary fix. Their complication, even compared with previous presidential elections, is that their new promises stack onto an extraordinary and unprecedented number of unsustainable promises already put into law. I understand why they are scared to death to tell us what reforms might really be required; we voters often jump on the honest candidate and, hence, bear some responsibility for what we get. But that means that in deciding for whom to vote, we must speculate on just which pledges either candidate would violate.

Should we prefer the candidate more willing to declare “oops” once elected?

Do we vote for the one whose future contradictions we believe will be less likely to affect our favorite interests?

Do we favor the politician more adept at dissimulating his past statements?

Consider many of the recent budget agreements and systemic reforms that required us to give up something. Reagan abandoned his opposition to removing tax breaks both in the budget agreements and the major tax reform legislation he signed. He also reversed his previously successful efforts to provide zero and often negative tax rates on some investments. Clinton abandoned his pledge for a tax cut soon after being elected. George H.W. Bush famously abandoned his “no new taxes” pledge. And while poor H.W.’s dissimulation efforts were unsuccessful, conservative and liberal pundits still place Reagan and Clinton high in their respective pantheons.

The president is the only elected official who represents all the American people. The office demands a higher order of integrity and just plain arithmetic discipline than does the role of candidate. In the end, therefore, we probably pick whomever we think better recognizes that the switch from candidate to president is more of a leap than a transition.

Should State Pension Plans Play Wall Street With Employees’ Money?

Posted: August 1, 2012 Filed under: Aging, Income and Wealth, Shorts, Taxes and Budget 2 Comments »In a recent examination of state pension plans, my colleagues and I discovered that states are increasingly tempted to solve their underfunded pension plan problems by acting a bit like Wall Street: hoping to make money out of the deposits they hold in a fiduciary capacity for their employees.

When a state plan has inadequate funding to pay promised benefits, someone eventually has to cover the difference. It could be taxpayers, those in the plan, or those who will be in the plan.

Because current and future taxpayers are already on the hook for a lot of past bills that have been left to them, states have tried to reduce their potential burden. Because existing state employees, especially those near retirement, have made plans for the benefits they have been promised, they have been asked to give up only a little. In many cases, their additional cost is confined to higher employee contributions for the remaining years of their careers only. Since the other two groups have been spared much of this burden, new employees have been asked to pay significantly more in both higher lifetime contributions and lower lifetime benefits than existing employees.

In our examination of one example, a reformed New Jersey plan, it turns out that many or most newly hired employees are unlikely to get lifetime benefits from the plan that are any higher than what they could earn with a modest interest rate—say, 2 or 3 percent—on their own contributions. Only those who work for the state for a very long time, such as 25-year-olds who stay between 30 and 40 years, get more.

The plan, however, assumes actuarially that the state will still earn a return of 8¼ percent on those employee contributions. In effect, the state hopes to make money out of their employee contributions just like a bank or Wall Street does: by leveraging up deposits, borrowing at one rate, and earning money at a higher rate.

A number of economists, actuaries, and accountants (see, for instance, Joshua Rauh and Robert Novy-Marx, Andrew Biggs, and, most recently, the Government Accounting Standards Board) have questioned the assumption of such a high rate of return.

We raise a further issue. Whatever the appropriate rate, how much should a state depend upon future employees to be net contributors to a pension plan, rather than net beneficiaries from it?

State Pension Reform: Is There a Better Way?

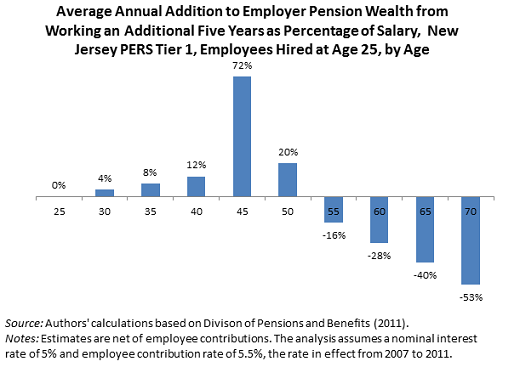

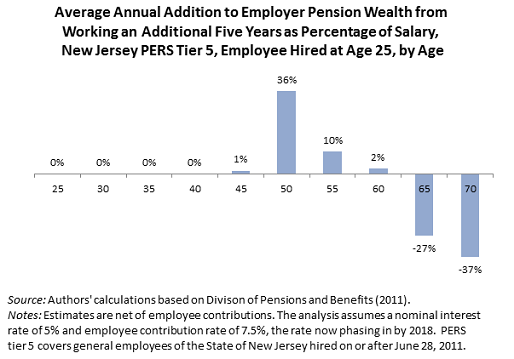

Posted: July 26, 2012 Filed under: Aging, Income and Wealth, Race, Ethnicity, and Gender, Shorts 1 Comment »Are the benefits of state pension plans allocated efficiently and fairly, and do they attract the best workers for the amount of money spent? Consider the graphs below for the state of New Jersey, which are somewhat typical of state pension plans in many other states. They show the annual pension wealth increments provided by the state for working for the state for five additional year for typical tier-1 (pre-reform) and tier 5 (post-reform) employees hired at age 25. Younger workers used to get very little, now they get nothing. Middle age workers get locked into the employment, regardless of how well it fits their skills or the needs of the state at that point. And older workers get very negative benefits, though at later ages than in the pre-reform era. For further details, see a paper (and two briefs) I published with Richard W. Johnson and Caleb Quakenbush, entitled “Are Pension Reforms Helping States Attract and Retain the Best Workers?”

The Pointless Debate Over the Social Security Trust Fund

Posted: March 24, 2011 Filed under: Aging, Columns, Income and Wealth, Taxes and Budget Leave a comment »Once again, policy-watchers and policymakers are fired up over whether Social Security needs to be fixed anytime soon. Some resort to pretty arcane debates over the trust fund to make their point. Won’t it take years to exhaust the trust fund? Are the bonds in the trust fund real? Is the trust fund a fiction? Was the trust fund raided? You know, it scarcely matters. All these debates are over a tiny sliver of the Social Security System—not over where the real action is.

What does matter is that Social Security expenses are expected to rise by about 50 percent—from about 4.3 to 6.3 percentage points of GDP—from 2008 to 2030, and taxes aren’t. As the baby boomers retire, higher expenses and less tax revenue mean that the national deficit will rise year after year.

Let’s take a quick look at the history of Social Security expenses and income. As the figure readily shows, Social Security has always been roughly a pay-as-you-go system. There was a tiny buildup of the trust funds at the beginning when people paid into the system but beneficiaries had not become eligible. In most years, the trust fund’s purpose was simply to cover potential cash flow problems if a recession or other major economic event hit. Then, in the mid-1980s, there was a slight buildup again as the large cohort of baby boomers swelled the ranks of the working population. But never have these trust funds held enough money to cover more than a tiny fraction of Social Security’s obligations.

Those who say we can wait 20 years to address Social Security’s solvency even though the system will soon be spending over 30 percent more than it collects in taxes have turned a blind eye to current and growing deficits. They seem to think that (1) we can count on income tax payers to raise more taxes, or we can cut other spending, or we can borrow more and pay interest to the trust funds as they move toward decline; or that (2) we can draw down assets (say, by borrowing more from China to pay off bonds in the Social Security trust fund) without consequences.

This is the mindset of a household that has saved $50,000 for retirement but has $300,000 in credit card debt and keeps charging more every year without paying down the balance. The parents in such a household plan on retiring for decades, earning less, and spending down their meager retirement savings in a few years, so they’re counting on their kids to bail them out. The parents keep insisting that the assets in their “fund” were real. The kids think the retirement fund is an accounting fiction. The parents remind the kids that they’d be in a worse pickle if it weren’t for the parents’ retirement fund. You can see how fruitless this conversation is when the operative fact is that the household is in a big financial hole that the decline in income and increase in expenses will only deepen.

How about raiding the trust fund? Those railing against this financial sin say that the country would have been better off without running a lot of non-Social Security debt even while it was accruing a tiny pot of money temporarily in its trust fund. That’s true, but then whose taxes were lower and other government benefits higher as a result? Often, the same people who cry foul that the (tiny) trust fund was raided. By that bizarre logic, the parents in our hypothetical household could claim that the kids should support them in retirement because the parents had raided their retirement fund by running up credit card debt.

So where did all the Social Security tax dollars go? Basically, to previous generations of retirees. Money in, money out. Did people get something out of their tax dollars? Yes, they did—support for their parents. Having already received that benefit, they can’t really lay claim to the same money twice. They can make a case that their kids should support them, just as they supported their parents. But it’s not that simple: newly retiring generations have fewer kids to support them and live many more years as retirees—21 years on average— than their parents did.

Those who would put off this debate may not have time on their side either: the Social Security problem will be fully ripe by about 2030—not 75 years from now. That’s well within the lifespan of people retiring today, not to mention most workers. If only politicians could see that far ahead!

Are You Paying Your Fair Share for Medicare?

Posted: January 6, 2011 Filed under: Aging, Columns, Health and Health Policy, Taxes and Budget Leave a comment »What do you pay in Medicare taxes? And what Medicare benefits can you expect? This issue—potent now that the first baby boomers are turning 65—was highlighted recently by Ricardo Alonso-Zaldivar in a widely read Associated Press story.

It’s no secret that early generations of Social Security beneficiaries got more out of the system than they paid into it. Beneficiaries in the 1940s and 1950s paid very low Social Security taxes for only a few years, then retired and received benefits for the rest of their lives. Until recently, in fact, almost all generations of retirees fared rather well. After all, the combined employer and employee tax rate for Old Age, Survivors, and Disability insurance, or OASDI, was kept low relative to benefits that would later be received. That combined rate equaled only 3.0 percent of earnings in 1950 and 6.0 percent in 1960, and it didn’t rise to its still-inadequate level of 12.4 percent until the late 1980s. Since most of these revenues weren’t saved, the increased OASDI tax rate supported ever-rising transfers to beneficiaries.

The most recent waves of retirees getting Social Security can make a stronger case that they have paid for their benefits. The complication is that their Social Security taxes mainly supported their parents in retirement, and the only way they can do as well in a money-in-money-out (at times partially funded) system is to foist higher tax rates on their children.

But let’s leave Social Security aside for the moment to consider an even bigger problem of the same stripe. Past and current retirees, and most working-age adults, will never pay for all their Medicare benefits. The government’s Medicare costs now top 3 percentage points of GDP and are headed to above 6 percentage points of GDP by 2055. But Medicare taxes and escalating premiums cover ranges from about 51 to 58 percent over time. To pay for the rest, we borrow from China and elsewhere, and use up ever-larger shares of income tax revenues, leaving ever-smaller shares for other government functions. Bottom line: without reform, current workers would continue to shunt many of their future Medicare costs onto younger generations, just as their parents did with Social Security.

Medicare’s problems, of course, extend well beyond Social Security’s. True, both systems must grapple with longer life expectancies and lower birth rates—thus reducing the number of taxpayers relative to beneficiaries. But Medicare also suffers from excessive cost growth. Structured like much other health insurance, Medicare essentially lets us consumers deal with doctors over what someone else (in our government or private insurance system) will pay. For years, numbers that Medicare actuaries and many others have been crunching have pointed to the system’s unsustainability. Sadly, the lack of agreement on an alternative has led us and our elected representatives to blink when it comes to tackling this core structural problem.

Not only does this current structure lead to more borrowing from abroad, it saddles future generations with most of the costs of all those marvelous, expensive discoveries from which we hope to benefit in retirement.

A better type of hip replacement comes along. A new drug for congestive heart failure. A more effective treatment for prostate cancer. Sign me up! Yes, these are real advances, and who doesn’t want insurance to cover them? The trouble is, the older among us are not required to work longer or pay for more than a minor share of these extra benefits. Providers, in turn, have come to expect ever-larger shares of national income as a reward for science’s leaps.

Oh, and by the way, most of us have a backup insurance policy in Medicaid. Indeed, the majority of people who end up in nursing homes for long periods turn to Medicaid for support.

What about government’s “trust funds”? Alas, they were never meant to cover future costs, and they can’t. Most of the money comes in only to go right back out. For one shining moment after the 1983 reform, when baby boomers had not yet started leaving the workforce, a slight surplus materialized. But the surplus represented only a tiny fraction of future obligations and will soon disappear (for Social Security, see figure 3 in http://www.urban.org/url.cfm?ID=412095).

In Medicare, payments to doctors, for instance, have come mostly from income taxes or borrowed dollars. While payments to hospitals mainly came from the Medicare tax, even that system has been so underfinanced that significant deficits are expected in the future. Without reform, we’ll continue to ask China and younger taxpayers to pay for those shortfalls.

In many ways, the numbers on lifetime benefits and taxes represent nothing more than another view on why our entire budgetary system is out of whack. This is not an economic problem that leads to a political one, but a political problem that threatens undesirable economic consequences. Only political reform of how we make economic decisions—addressing inconsistent promises for low taxes and high benefits that people have come to expect—can move us away from a system where promised benefits supposedly rise forever faster than GDP and where future, not current, workers must be left to bear most of the costs and consequences.

Can Budget Offices Help Us Address Demographic Pressure?

Posted: September 20, 2010 Filed under: Aging, Columns, Income and Wealth, Taxes and Budget Leave a comment »As pressures mount on the nation’s long-term budget, the Congressional Budget Office now views the aging of the population as the main stressor and health care costs as a close second. Yet, CBO and the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) have traditionally offered only limited analysis and estimates on addressing these demographic concerns, often leaving them to the Social Security Administration, which focuses only on the Social Security piece of the budget puzzle.

Accordingly, when groups like the president’s budget commission meet, they get too few options on how government might adjust to the two distinct forces mistakenly put under a single “aging” banner: (1) longer lives and (2) fewer children (new workers) than previous generations. For better and often worse, reform groups frequently stack up reforms by their budget impact. But where there’s no estimate, there’s no political traction and, alas, no action.

If we want real budget reform, we need to get over this hurdle.

To start, we have to understand what puts it there in the first place. Put simply, we may soon see a fairly dramatic drop in the proportion of workers in the population and the taxes they pay, along with a commensurate increase in the number of people who depend on government for support. As baby boomers retire, this triple whammy on output, revenues, and spending intensifies.

The hit on government is most often discussed as a Social Security problem. That’s misleading. The real, far bigger problem is fewer people producing less output and generating far less income for themselves. In turn, these individuals start saving less, spending down their savings sooner. When it comes to government, they start paying less income tax and start relying more on programs like Supplemental Security Income (SSI) and Medicaid—close to half of the latter’s budget pays for long-term care. All these repercussions are in addition to any effect on Social Security taxes and benefits.

If policymakers could relieve some of this demographic pressure—particularly by avoiding some of the projected drop in employment rates among those in late middle age and older—then revenues rise without tax rate hikes, and those higher revenues support additional benefits at any tax rate. Such a win/win scenario should be easy for both Republicans and Democrats to embrace.

So what’s stopping them? For one, the ingrained habit of raising this issue strictly as a Social Security problem even though the Social Security Trust Fund balance doesn’t tell the whole story.

But there’s another, more complicated reason. Budget offices seldom project changes in national output and income from reforms. Politicians assert that their every proposal promotes growth by helping people, improving incentives, or reducing deficits. As Congress drafts and redrafts bills, estimators don’t have the ability—or the time—to rank every proposal by its impact on growth. Also, evaluating all legislation affecting the budget by very uncertain impacts on national income gives estimators too much power over issues that require a broader legislative debate.

In practice, there are exceptions. The Social Security actuaries do project some changes in long-term behavior when it affects Social Security. And unified budget projections (as opposed to cost projections of congressional bills) do incorporate some estimate of where the economy is headed.

Still, more generally, the budget impacts of a populace that works more and longer aren’t going to emerge from traditional budget and Social Security analyses. A recent CBO report on Social Security reform options that affect Trust Fund balances, for instance, didn’t touch on proposals to bump up the early retirement age or to backload benefits more to older ages. These proposals trade off fewer benefits in early retirement for more benefits in later retirement, but they generally don’t help the Social Security Trust Fund balances unless they increase work effort. Thus, once CBO excluded estimating behavioral shifts, as well as impacts on income tax revenues, it effectively excluded the proposals from the report. Such proposals, by the way, have another non-Trust Fund objective: improving protections for the frail by reorienting payments to when people are truly old.

As another example, a few years ago the CBO staff wisely decided to check out statements that budget problems were driven almost solely by health care cost growth. But even when the analysts provided credible measures of the relative budgetary effects of health cost growth, demographic shifts, and their interaction, they didn’t venture to estimate the impact on general revenues of any projected drop in share of the population employed.

Of course, estimating these impacts is no piece of cake. Budget offices lean toward conservative estimation on grounds that large behavioral shifts, however frequent or powerful, are hard to predict. That’s one reason budget offices have underestimated the cost of, say, Medicare as implemented or guarantees for Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. But budget analysts often underestimate upside potentials of legislative actions as well.

My work with Brendan Cushing-Daniels, for instance, suggests that the signal government sets by fixing Social Security retirement ages significantly affects the decision of when to retire—independently of whether there are any real economic gains from retiring at those ages or later (see http://www.urban.org/publications/412201.html). But think about trying to estimate the ultimate effect of changing those signals amid demographic shifts unlike any the developed world has ever seen. (I’m emboldened a bit here because one of my past predictions is proving correct: Social Security underestimated the work efforts of older workers once earlier retirement was not so easily supported by baby boomers and women entering the workforce in droves.)

Since budgeteers have to live with some uncertainty, one key to successful reform is not to depend so much on estimates being right, but to set in place triggers that keep a system in balance as behavioral patterns shift. If reform increases work, for instance, then fewer other benefit cuts or tax increases would go into effect.

Such reform options won’t even be considered as long as the budget offices can’t improve ways to analyze and estimate proposals addressing these demographic shifts. But with looming deficits threatening to hamstring growth, opportunity, and the safety net itself, there’s no longer much time to wait.

How Middle-Age Retirement Adds to Recession Woes

Posted: June 2, 2010 Filed under: Aging, Columns, Race, Ethnicity, and Gender Leave a comment »As the nation struggles to deal with both an unsustainable budget and an economy in need of growth, one really bad idea needs to be nipped in the bud. Expressed in various forms, the idea is that baby boomers’ retirement isn’t really a problem until the economy fully revives, that people in late middle age should quit to make room for younger workers, and that the multi-decade failure to adjust retirement ages for longer lives is a can we can keep kicking down the road. Let’s face it: our retirement system for middle-agers is hurting us financially right now.

Bad economics, this idea in its various guises also invites a less-than-full economic recovery. The Great Recession is starting to spark notions heard in the Great Depression, when older workers were also encouraged to retire. It didn’t do any good: employment rates stayed low for over a decade. It was a bad idea then, and it’s a bad idea now.

The economy-wide perspective differs from the firm-level perspective: when people work more, they generate income and spend that income on goods or services—increasing not just the supply of workers, but also the demand for other jobs. Yes, a worker who hangs onto a $50,000 job might prevent someone else from taking that exact job. But that worker then spends (or invests) $50,000 on goods and services that others must produce in other jobs.

Let’s put it another way. Suppose a firm in Detroit fires a younger worker, who makes unemployment claims, and an older worker, who decides to retire earlier than planned but still doesn’t get counted in the ranks of the unemployed. Is Detroit any better off because the older worker lost his job, even though, unlike the younger worker, he didn’t add to unemployment statistics? Of course not. They both add to Detroit’s recession woes. And they both add to the “nonemployment” rolls.

How much of an issue is the retirement of older workers? In the short run, it’s less important than job losses due to the collapse of the financial and housing markets. Longer run, however, it may be far more serious. If people simply retire at the same ages over the next 20 years as they do today, then the employment drop is equivalent to an increase in the unemployment rate of close to one-third of 1 percent every year. Two decades or so from now, the increase in nonemployment would have about the same effect as a 7 percentage point increase in the unemployment rate. And this increase would be permanent, not just a temporary, recession-led blip.

We don’t really have to wait 20 years for the bad economic news to register either. Contrast how we got out of other recessions in earlier decades. Government deficit-led demand alone didn’t do the trick. Counting both those employed and those looking for work, we also had a labor force increase of 29 percent in the 1970s, 18 percent in the 1980s, and 13 percent in the 1990s. This last decade is more of a mixed bag, mainly because of the recession, and for each of the two decades from 2010 to 2030, the Census is expecting increases of only about 7 percent. Even that projection assumes some increase in the proportion of older age groups that work. Despite many past recessions with large annual increases in unemployment, by the way, 2009 was the first year in almost six decades with negative labor force growth.

Additional labor force participants didn’t just increase the supply of workers; even when they started out with meager jobs, they boosted production and income and the demand for goods and services that helped pull the nation out of past recessions. With lower labor force growth today, there’s less of the extra demand that a large net increase in the workforce stokes.

Well, you might say, government can come to the rescue by making up for lost wages. To some extent, that’s true. But government help doesn’t stop unemployment or nonemployment from rising and taking a toll on the economy as a whole, even if that help lessens the decline in demand. In any case, nobody who does arithmetic pretends that government can run large enough deficits to continually make up for everyone’s lost income. Moreover, we’ve hit the point where efforts at deficit reduction are going to be decreasing—certainly not increasing—government demand.

How about the effect of the international economy? Doesn’t any multiplier or snowball effect—from one nonemployed person leading to another—weaken when demand can come from abroad, not just from home? True again. But, by the same token, any multiplier effect from government-created demand also shrinks. That said, the developed world shares both a slowdown in labor force growth and a recessionary slowdown in demand. In both cases, a mutual response is better than an individualized one.

My basic point is simple: when it comes to looking at recessions and the potential for renewed growth, look at the nonemployment rate, not just the unemployment rate. The first wave of baby boomers hit 62—the youngest you can get Social Security benefits—in 2008, and that downtick in labor force and employment came just as the recession began to hit. Boomer retirement may add only moderately to the nonemployment rate in any one recession year, but, unless moderated, its negative force will build steadily year after year for decades.

Encouraging work in late middle age alone won’t end the recession or clean up our fiscal mess. And many of those facing nonemployment, whether older or younger, have little control over the situation. But when our elected officials delay action—for instance, continuing to encourage retirement in late middle age and failing to start dismantling barriers to work at older ages—they hurt the economy recovery now, not just economic growth over the long term.

On the positive side, my reading of the data tells me that there’s a large undercurrent of demand for older workers, who have now become our largest store of underused human capital and potential. But activating that potential partly requires lowering the barriers and dams in the way. If I’m right, older workers can significantly boost economic output, increase government revenues, and add to their own incomes. Along the way, they can help us recover from recession—if we let them.

And Now Something for Our Most Recession-Weary Workers

Posted: April 1, 2010 Filed under: Aging, Columns, Income and Wealth, Job Market and Labor Force, Taxes and Budget Leave a comment »With economic recovery from the deep recession in view, a double-headed challenge remains. Reducing the deficit requires cutting back government spending, but we still need to promote employment and work, and that won’t come free. Given this administration’s progressive leanings, its attention to low- and moderate-income workers is surprisingly modest.

So how hard is it to spend less overall but more on lower-income workers? Presidents George H.W. Bush, Bill Clinton, and Ronald Reagan all expanded wage subsidies for some low-wage workers through the earned income tax credit (EITC) while and reforming taxes and significantly lowering the deficit.

Shifting policy toward low-income workers brings other benefits, too.

It increases employment more per dollar spent than many current subsidies that go to higher-income individuals and to those who do not work at all.

It helps reduce the long-term costs of added crime and depression borne of long spells of unemployment.

Done right, it can reduce the marriage penalties in many wage subsidies and welfare programs.

This administration and Congress have hoped that their biggest initiative—saving and subsidizing Wall Street and lowering borrowing costs—would trickle down benefits for everyone else. Maybe so, but more money for low-income workers can also trickle up. And it costs far less to subsidize a low-wage job than a high-wage job.

The biggest direct wage subsidy enacted so far has been the Making Work Pay tax credit. For most eligible working households, however, it’s just a $400 credit ($800 for married couples). It’s really not a jobs subsidy so much as an across-the-board tax cut to spur consumption.

The Obama administration’s latest ventures include such items as a $5,000 tax credit for small businesses for each new employee hired this year. Puny relative to the economy’s size, this incentive also gets mired in all sorts of definitional issues. What is a small business? (Your maid service? Your friendly billionaire’s 20th venture?) Who’s new? (Your kid? Someone already on your to-hire list?). Why discriminate against struggling businesses? And why not count the worker they would otherwise let go?

Wage subsidies for low- and moderate-income earners, by contrast, traditionally have fans on both the left and the right. More progressive than most other subsidies, they also offer an alternative to welfare and unemployment insurance, which can discourage work. Indeed, past EITC increases helped give low-income households a foothold that allowed President Clinton and the Republican Congress to reform and deemphasize welfare in 1996.

The Obama administration does support expanding EITC for families with three or more children a bit. And, arguably, its proposed extension of the child credit to include some very low earning households who generally don’t owe taxes subsidizes part-time or part-year work. Nonetheless, most moderate-income workers are excluded from these expansions, which send money mainly to one-parent households and only to households with children.

What’s the most sensible approach? For my money, it’s concentrating additional work support to the largest groups now left out: low-wage single workers and many married, two-earner, low-wage families. Especially key is an EITC-like subsidy for the low-wage worker based mainly on his or her earnings.

That way, we reach single people with no kids, including many of the males hardest hit during this recession and still ineligible for most government programs. And we reach many households who marry or contemplate marriage, only to realize that tying the knot means losing or jeopardizing thousands of dollars worth of EITC, Medicaid, welfare, and housing subsidies annually. Better to stay unmarried, even if living together.

And if we don’t take these steps? For starters, we ignore the fundamental policy lessons that leaving millions of productive people jobless has long-lasting costs. Unemployed people are more depressed, less entrepreneurial, more risk averse, more bored, more inclined toward substance abuse, and more likely (especially if they are young men) to turn to crime. Just as failing to create jobs for more Iraqis right after Saddam Hussein’s fall was a big foreign policy mistake because many turned to more violent pursuits, neglecting job creation now could be a colossal domestic policy mistake that plays out long after our economy is back on its feet.

Our national sense of fair play is at stake here too. The recession hurt low-income workers most, but they were largely left out of most stimulus programs.

Policy two-fers are often rare. But this policy shift is a five-fer that appeals to both liberal and conservative principles: reduced spending, greater progressivity, higher employment per dollar spent, reduced crime and depression, and fewer penalties for marriage. And with predictions of only slow employment growth ahead, the timing is right for confronting unemployment more strategically.