Mr. Speaker: Redefine Your Role

Posted: October 22, 2015 Filed under: Columns, Taxes and Budget Leave a comment »On October 22 Paul Ryan announced he “will gladly serve” as Speaker of the House if he can unify the Republicans around his vision for the party and the Speaker’s role within it. He faces an uphill battle: Mo Brooks of the House Freedom Caucus has already voiced his concern at Ryan’s reluctance “to do the speaker job as it’s been done in the past.”

But what if the job, not the person filling it, has become the problem? What if the expectations now placed on any Speaker of the House are so unreasonable that no one can meet them? What if the procedures of both the House and the Senate simply cannot meet modern legislative needs? Then we had best not place our hopes on the right person meeting wrong expectations.

Instead, to succeed, the next Speaker of the House must radically redefine that role and how the House conducts business. Ryan himself has stated that “we need to update our House rules…and ensure that we don’t experience constant leadership challenges and crisis.”

At least since the time of Newt Gingrich, an extraordinary amount of the House’s power has been concentrated in the Speaker’s office (although I sense that John Boehner struggled to simultaneously maintain that power and disperse it). Consider some consequences of this convergence:

- Acrimony. The antipathy that accompanies all concentrations of power has spread not just between political parties, but within them as well. One of Republican Congressman Mark Meadows’ chief complaints about John Boehner was that the Speaker had attempted “to consolidate power and centralize decisionmaking.”

- Attention to party rather than nation. In recent years, the House has attempted to confine enactments to items that receive broad consensus among members of the majority party. But the US Congress cannot operate like the British House of Commons, where party leaders become prime ministers. Our Constitution separates the country’s executive and legislative functions, slowing down reforms both good and bad. Although we can’t imitate most British parliamentary procedures, I do think the British tradition of the Speaker resigning his or her party position to serve all House members is worth looking into.

- Inefficient policymaking. Congressional committees are much weaker than they were 20 years ago. At one time the Ways and Means Committee was the most powerful in the House, and its chair was often as powerful as the Speaker. Working closely with the Senate Finance Committee, Ways and Means often took on the unpopular task of identifying how to increase taxes or cut the entitlement spending under its jurisdiction so the nation’s balance sheets maintained some semblance of order. However, once much of the committee’s power was relegated to a Speaker whose job revolved around keeping members of his party happy, necessary economic choices and the compromises that need to be ironed out in a small group— often including members of the other party—couldn’t be developed or sustained. In turn, the complicated, technical, details of policymaking—whether over a tax cut or a health care expansion—often got messed up when put under the purview of people with limited expertise on the particular laws being reformed.

In sum, a Speaker can’t serve either nation or party well when so much power is concentrated in one office, the acrimony surrounding such concentration rises so high, too many party obligations weaken the Speaker’s ability to focus on legislative obligations, and the assumption that the primary role of the Speaker is to promote partisan politics weakens the ability of the House to make tough choices and creatively draft detailed legislation.

Of course, the Speaker cannot reform his own role in isolation from other roles and rules within the House. As already noted, more legislative power can be returned to committees, and party politics can be relegated to party whips or other officers with no obligations to the House as a whole. Here I agree with many Freedom Caucus members, who claim they want to empower committees, but I disagree that this means that a small group within a majority party should be more likely to get its way. The job of the committee chair, just like the job of the Speaker, is to create legislation that will form enough consensus to pass the House, the Senate, and the presidential veto pen.

The House, led by the Speaker, must also start to tackle other obstacles to legislation. Here are three to start. First, political staffs should be reduced in size and nonpartisan staffs increased. The House budget and tax-writing committees can look to the Congressional Budget Office or Joint Committee on Taxation for objective analyses of legislative proposals; other committees lack independent reality-checkers. Second, the congressional budget process is long overdue for overhaul. As a former head of the Budget Committee, Paul Ryan should be all over this one. Third, the wasteful replication of hearings on the same subject matter across House committee jurisdictions should be curtailed.

There’s no guarantee that any particular reform will suddenly make the House more productive. But continuing under current expectations and processes almost assuredly insures that both the House and the Speaker will fail to meet their fundamental constitutional responsibilities to legislate for the nation.

Disgruntled minorities will always seek whatever power the existing structure grants them. The next Speaker can only meet his huge challenges by boldly changing the rules of the game he is called to officiate.

Millennials: Today’s Underserved, Tomorrow’s Social Security and Medicare Bi-millionaires?

Posted: September 16, 2015 Filed under: Aging, Columns, Health and Health Policy, Income and Wealth 2 Comments »When America’s Social Security system was first established in 1935, the public was deeply concerned about the fate of our elderly, who were then on average poorer than the rest of the population, less capable of working, more likely to work in physically demanding jobs, and less likely to live close to two decades past age 65. Today’s concept of Social Security was actually only one part of an act aimed at meeting the needs of the poor, old, needy, and unemployed of all ages.

In the early decades through the 1960s, Congress expanded old-age supports largely to cover important gaps such as spouses and survivors, disability, health insurance and inflationary erosion of benefits. Today, however, Social Security grows based on past laws that preordain increases in old-age support, largely independent of how the needs of the elderly and nonelderly have evolved or will evolve.

In a newly released study, Caleb Quakenbush and I find that a typical couple retiring today is scheduled to receive about $1 million in cash and health benefits; many millennials will receive $2 million or more. In effect, we’ve now scheduled many young adults to be future Social Security and Medicare bi-millionaires. And the growth continues; the succeeding generation, born early in the 21st century and sometimes referred to as the homeland generation or generation Z, is scheduled for significantly higher benefits. Add to these amounts additional Medicaid expenditures that also go to many elderly if in a nursing home for any extended period of time. (These figures are “discounted”—that is, they show what amount would be required in a saving account, at age 65, earning real interest, to provide an equivalent level of support.)

In fact, a very high proportion of all growth in federal government spending over the next several decades is currently scheduled for Social Security and Medicare. Almost all other spending, whether for children or defense, infrastructure, or the basic functions of government, already is held constant or in decline in absolute terms, and sometimes in a tailspin relative to the size of the economy and the federal government. Only other forms of health care and retirement support, interest costs, and tax subsidies are on the rise.

Such developments are hardly sustainable. Simple math tells us that they will continue to impose costs that the millennials and younger generations are already experiencing: cuts in other benefits for them and their children, higher taxes, and reduced government services when they are in school, working, or middle-aged.

Next time you read a headline on growth in student debt, the falling real value of the child credit, declines in federal spending on education and infrastructure support, or fewer soldiers and sailors, keep in mind that these stories all follow as a consequence of where past Congresses have directed almost all government growth. Of course, governments almost always spend more as an economy and the tax base expand, whether the size of government relative to the economy grows, stays constant, or declines. But past governments traditionally allowed future legislators and voters to choose what to do with those additional revenues; they weren’t stuck with leaving that decision to prior legislators.

How did we get here? As Congresses and presidents added to Social Security over the years, it became more generous. Health insurance was expanded to cover hospitals and doctors, then more recently under President George W. Bush, drug benefits. Cash benefits were raised through various enactments under Republican and Democratic presidents alike.

One big culprit is the retirement age, which, by remaining stable on the basis of chronological age, does not remain stable on the basis of years of support, which increase as people live longer. A typical couple retiring at the earliest retirement age now receives benefits for close to three decades, which is roughly the expected lifespan of the longer living of the two. Spend $25,000 (discounted) per year on each person, but then do it for 20 years or so per person, and you come up with a figure like $1 million for a couple.

Since the 1970s, real annual benefits have also been growing automatically as wages rise. In fact, the combination of “wage indexing” and failure to adjust for life expectancy schedules Social Security to rise forever faster than the economy.

Then, of course, there are the health care costs. People are getting more years of medical support as they live longer. Plus, the federal government has never effectively tackled the increasing costs that result almost inevitably in a system where you and I can bargain with our doctors over whatever everybody else should pay to support our next procedure or drug.

By the way, none of these calculations account for the decline in the birth rate and its effect on the number of workers available to support such benefit growth. Roughly speaking, the taxes available to support any system decline by about one-third when the ratio of workers to retirees falls from 3:1 to 2:1.

We’ve traveled a long distance from 1935’s legislation and its goal of addressing the needs of people of all ages.

Reforming Disability Policy: Tough Choices Required

Posted: August 14, 2015 Filed under: Columns, Income and Wealth, Taxes and Budget Leave a comment »Setting disability policy is tough. Very tough. It’s tough empirically to measure and distinguish among degrees of disability or need. It’s tough legally and administratively to draw boundaries without excluding some sympathetic person or giving an inappropriate level of benefits to someone whose needs can’t fully be assessed. It’s tough economically to transfer resources to people with disabilities without setting up perverse incentives that separate them from the workplace and their fellow workers. It’s tough socially because the needs are so great.

Disability policy has gotten increased attention recently because the Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) trust fund is unable to pay our current benefits through 2016. But reform should involve more than money. By defining eligibility for benefits partly by the inability to work, SSDI and other federal disability policies effectively discourage recipients from trying to support themselves. If they work, they lose their benefits. This needs to be fixed. But how?

In a recent conference sponsored by the McCrery-Pomeroy SSDI Solutions Initiative (disclosure: I helped organize the initiative and still serve as advisor), no one advocated reducing benefits to bring SSDI back into balance. Nor did anyone suggest merely raising taxes.

Most speakers talked about the need to modernize US disability policy—in particular, to offer opportunities for people who want to work, can work at some level, or can keep working if they receive help when they first develop a health problem or impairment. Speakers recognized that work is therapeutic and that disability policy should account for the factors that can affect someone’s disability differentially across his or her lifetime, such as the episodic nature of many mental illnesses and the kinds of rehabilitation that can prove helpful to different people at different times.

Disability policy is exactly the same as other policy in one respect: it contains a fairly precise, even if implicit, calculus of what and whom will and won’t be funded. So, any reform to the policy must address the balance sheet.

The President and Congress seem ready to punt on dealing with SSDI, effectively covering shortfalls by transferring money from Social Security Old Age Insurance (OAI). Despite the pretense, such a move is not costless. Today’s taxpayers and beneficiaries won’t need to pay for the growing costs of SSDI, but future taxpayers and beneficiaries—of SSDI or other federal programs—will inherit even higher SSDI or OAI deficits, along with their compounding interest costs. Meanwhile, today’s catalyst for reform is neutralized.

As I listened to the McCrery-Pomeroy conference speakers propose adding work incentives and supports to SSDI (a suggestion I lean favorably toward, despite many design issues), it struck me that the proponents were implicitly suggesting that there is a better way to spend the next SSDI dollars than simply expanding the current program. If those proponents genuinely believe that work incentives and supports are the right way to direct additional dollars, then they also imply that we ought to look at how Congress already has scheduled additional dollars to be spent.

Some advocates may try to claim that we shouldn’t make such marginal budget comparisons. When I co-wrote a book on programs for children with disabilities, my fellow authors and I were criticized in one review for noting simply that the principle of progressivity requires figuring out who needs support the most. Such a critique ignores that we have to make choices, so we may as well do them as best we can. No one, proponent or opponent of current or any reformed law, can get around the simple fact that dollars spent one way cannot be spent another.

Let me put this in terms of the politics. Politicians never want to identify losers because then we voters crucify them. They want to operate on the give-away side of the budget: spending increases and tax cuts. So how can we give politicians some protection to reform disability policy if you and I know that putting relatively more money into work supports changes the nature of SSDI and prevents some other use of the money?

Here’s one way: emphasize the long-term dynamic that reform in a growing economy makes possible. Counting everything from health care to education to disability policy, our social welfare budget now spends about $35,000 annually per household. As the economy grows over time, the number is going to increase—perhaps to $70,000 if the economy doubles in another few decades. We don’t need to cut back on disability programs absolutely in order to allocate a share of those new marginal dollars to different approaches. We simply need to focus the growth of those future budgets.

SSDI and OASI grow automatically over time because benefits are indexed for real growth in the economy over and above inflation. No legislator determines that today’s additional expenditures should be directed one way or another; it’s in a formula set decades ago. Why not consider reducing that automatic growth to finance more subsidies and supports for people who want to keep working? What about capping growth—at least for those getting maximum benefits? What about re-allocating some of the federal health budget, where so many of the dollars are captured by providers rather than consumers, to help pay for work supports?

Or what about cutting back on those features of SSDI that add to the anti-work incentives? For example, what about paring the ability to increase your benefits by about 30 percent if you retire at age 62 on disability insurance instead of old age insurance, at least for people at higher incomes? Or at least not increasing that disability insurance bump, as now happens automatically when the full retirement age increases?

We can shift toward a more modern disability insurance system, but only when we face up honestly to the trade-offs implicit or explicit in every system. We will never move disability policy away from its antiwork emphasis if we’re not willing simultaneously to address the way we put additional resources into the current prevailing system. And, as best I see it, that is just what a scared Congress and president are about to do.

Why Health Cost Growth Increases after Estimators Say it’s Slowing: Observer Effects and Feedback Loops

Posted: August 3, 2015 Filed under: Columns, Health and Health Policy 2 Comments »“Health cost growth has slowed down, we think. So let’s increase health costs.” This is the federal government’s apparent response to some recent sanguine estimates about the future of health cost growth. We might call this response a policy version of the “observer effect,” where the mere observation of reality changes that reality. In this case, the observation that health care costs may be increasing more slowly than expected creates a political reality in which fewer efforts are exerted to keep costs under control.

Projections based on past historical trends are fraught with danger. The influence of government policy sits near the top of that danger list. Since federal and state spending plus tax subsidies now cover about 60 percent of the health care budget, government legislation decides much of what the nation will pay for health care. Speaking technically, policy is endogenous to—or influential on—the past trends we measure.

Logically, then, future legislation too has a powerful effect on the direction of health costs. But possible policy changes are an unsteady foundation for cost projections. Government agencies like the Congressional Budget Office try to get around this dilemma by treating policy as exogenous to—or not influencing—cost projections. That way, those agencies can display the implications of current laws, even when those laws imply a growth in cost that is unsustainable.

But health researchers, the public, or elected officials who conclude that past trends will simply continue often fail to account for how policy decisions feed health costs and vice versa. US health care insurance, including that provided or subsidized by government, still offers fairly open-ended access, allowing consumers to spend more and providers to earn more at others’ expense. If policymakers interpret slower cost growth to mean they need fewer new cost-reducing measures and can even rescind some old ones, then as a consequence health costs are going to rise faster.

It now seems clear that Congress and the Obama administration have responded to these new estimates by taking a more lackadaisical attitude toward controlling costs. Two pieces of evidence:

- Congress has long squabbled over how to deal with legislation that tried to make the growth in Medicare costs sustainable by cutting payment rates to doctors for certain procedures. Past efforts led to “doc fixes” that held off such cuts for a while and let them accumulate. All was not lost: according to the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, these annual forestalling actions involved significant other health cost cuts to pay for each fix. In 2015, however, Congress threw in the towel: it abandoned the old requirements on doctors while providing limited real offsets.

- Many Republicans and some Democrats now oppose a tax imposed under Obamacare that requires insurance companies to pay a tax on high-cost insurance plans (plans whose value exceeds $27,500 a year for a family and $10,200 a year for an individual in 2018). Admittedly an imperfect device, the tax did address both conservative and liberal concerns, backed by solid research, that offering a tax subsidy for costs above a cap mainly led to higher health care costs while doing little to expand coverage. Abandoning the high-cost plan tax would effectively increase health costs even more.

Harder to substantiate are cost-controlling initiatives that are abandoned or never undertaken. For instance, President Obama has removed some of the health saving initiatives that used to be in his budget—such as limits on state gaming of Medicaid matching rates—presumably because he thought these initiatives were unlikely to get through Congress, or he had enough health care fights on hand. How much have payment advisory commissions felt that they could let up on new suggestions to reduce prices? In general, how does a perceived reprieve from pressure lead any of these actors to kick the can down the road to their successors or at least until after the next election? Paul Hughes-Cromwick of the Altarum Institute also asks whether something similar doesn’t go on in the private sector: for example, would specialty drug makers price new entries so aggressively (e.g., Sovaldi for Hepatitis-C or even Jublia for toenail fungus) if we weren’t simultaneously coming off historically low spending growth?

My advice to estimators: include a feedback loop to demonstrate how your estimates affect the behavior of those making decisions on the basis of your estimates. Your projections of lower health cost growth may end up increasing health costs.

Combined Tax Rates and Creating a 21st Century Social Welfare Budget

Posted: June 26, 2015 Filed under: Children, Columns, Income and Wealth, Taxes and Budget 1 Comment »In testimony yesterday before a joint hearing of two House subcommittees, I urged Congress to modernize the nation’s social welfare programs to focus on early childhood, quality teachers, more effective work subsidies, and improved neighborhoods. One way lawmakers can shift their gaze is by considering the effects of combined marginal tax rates that often rise steeply as people increase their income and lose their eligibility for benefits.

While some talk about how we live in an age of austerity, we are in fact in a period of extraordinary opportunity. On a per-household basis, our income is higher than before the Great Recession and 60 percent higher than when Ronald Reagan was elected President in 1980.

A forward-looking social welfare budget should not be defined by the needs of a society from decades past. Two examples of how our priorities have shifted: Republicans and Democrats didn’t always agree on the merits of Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) or the Earned Income Tax Credit, yet they agreed on the need to shift from welfare to wage subsidies. Ditto for moving from public housing toward housing vouchers.

I sense that both the American public and its elected representatives are united in wanting to create a 21st century social welfare budget. That budget, I believe, should and will place greater focus on opportunity, mobility, work, and investment in human, real, and financial capital.

However, for the most part, our focus has been elsewhere. As I show in my recent book Dead Men Ruling, we live at a time when our elected officials are trapped by the promises of their predecessors. New agendas mean reneging on past promises. Even modest economic growth provides new opportunities, but the nation operates on a budget constrained by choices made by dead and retired elected officials who continue to rule.

For instance, the Congressional Budget Office and others project government will increase spending and tax subsidies by more than $1 trillion annually by 2025, yet they already absorb more than all future additional revenues—the traditional source of flexibility in budget making.

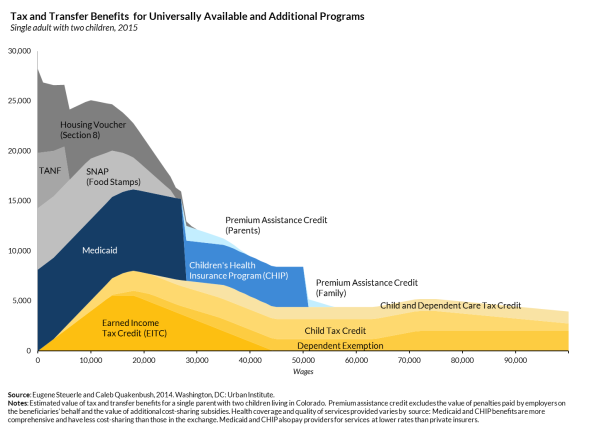

I am concerned about the potential negative effects of these programs on work, wealth accumulation, and marriage of combined marginal tax rate imposed mainly on lower-income households. To see how multiple programs combine to reduce the reward to work and marriage, look at this graph.

For households with children, combined marginal tax rates from direct taxes and the phasing out of benefits from universally available programs like EITC, SNAP, and government-subsidized health insurance average about 60 percent as they move from about $15,000 to $55,000 of income. This is what happens when a head of household moves toward full-time work, takes a second job, or marries another worker.

Beneficiaries of additional housing and welfare support face marginal rates that average closer to 75 percent. Add out of pocket costs for transportation, consumption taxes, and child care, and the gains from work fall even more. Sometimes there are no gains at all.

While there is widespread disagreement on the size of these disincentive effects on work and marriage, there is little doubt that they exist. One solution: Focus future resources on increasing opportunity for young households. Make combined tax rates more explicit and make work a stronger requirement for receiving some benefits.

This post originally appeared on TaxVox.

How to Pay Zero Taxes on Income of Millions of Dollars

Posted: June 24, 2015 Filed under: Columns, Taxes and Budget Leave a comment »Remember when people complained that hedge fund managers and private equity firm owners paid a lower tax rate than many workers? Or when Warren Buffett said he shouldn’t pay a lower rate than his secretary? In those cases, investors were benefiting from low capital gains rates, but at least they paid some tax.

Now, thanks to Roth accounts, a special form of retirement savings, investors and even their children pay close to zero tax on huge sums of income. While this scheme can create significant future government budget shortfalls, my attention here is on how our tax code favors those who understand how to play this Roth-account game.

You got a hint of what might be possible when Governor Romney disclosed that he had over $100 million in his individual retirement account. However, this money was in a traditional IRA, taxable upon distribution, not a Roth IRA, where once a modest tax is paid up front, then all future income from the account escapes tax. Thus, Romney missed out on some of the tax benefits available to Roth holders.

The Taxpayer Relief Act of 1997 first made such accounts possible. At about that time, I warned in Tax Notes Magazine about how some investors could use Roths to avoid almost all tax on significant amounts of income. But I didn’t have a smoking gun, since I was anticipating future accruals on this then-new option. Tax professionals who put high-return hedge fund or private equity return assets into a Roth for wealthy clients have no incentive to disclose the details of these deals.

But a recent article by Richard Rubin and Margaret Collins for Bloomberg describes a redesigned retirement plan of Renaissance Technologies that allows employees to put retirement monies into Medallion, a hedge fund that historically has produced extraordinary high returns. My colleague, Steven Rosenthal, examines the tax implications and questions the future role of the Labor and Treasury Departments in these developments.

But you don’t need to work for a private equity firm or hedge fund to benefit. Let’s start with the tax sheltering opportunity available to almost anyone willing to invest far into the future and who earns no more than the normal long-term rate of return on stocks.

Suppose a 25 year-old taxpayer puts $10,000 in Roth accounts, perhaps helped out by parents. Once he pays a small upfront tax on the contributions, the tax on these accounts is now totally prepaid. He will never owe another dime. If stocks provide a traditional historic return of, say, 9 percent per year, the portfolio would grow to $483,000 by age 70, the age at which people must withdraw from traditional retirement accounts but not Roths. Make a few such deposits, and soon millions of dollars of income can escape tax.

But 9 percent represents an average return, chicken feed compared to the successful private equity investor, inventor, entrepreneur, or small business person. If they are insiders or somehow know, they might well know that they are likely to generate 15 percent per year over time. Others might also generate this higher return because of invention, luck, or simply leveraging up their returns. If the investment returns 15 percent annually, a $10,000 deposit held for 45 years grows to $5.4 million by age 70.

Perhaps you think the example of a 25-year old depositing money until age 70 is exaggerated. But it understates the more extreme cases. A Roth IRA can be held much longer than 45 years, e.g., a 35 year old living to 90 can leave the money to his kids who must withdraw the money only gradually after the parent’s death, so in this case complete tax exemption would last 55 years, and partial exemption would extend outward toward a century.

Think what this does for the fairness of a tax system. People who turn out to make millions of dollars of income on their investments will often pay no more tax (up front or down the road) than people who make little or nothing on their saving. To be clear, I’m saying dollars of tax, not rate of tax, would often be the same. The unsuccessful will be taxed the same as the successful, violating the whole notion of proportionality, much less progressivity, in taxation. I can think of almost no other tax provision, whether in an income or consumption tax, that goes so far in violating the notion that those who either make more money or consume more can afford to pay more tax.

This post originally appeared on TaxVox.

Empowering the Next President—and the Next Congress

Posted: June 3, 2015 Filed under: Columns, Economic Growth and Productivity Leave a comment »“This is a trade-promotion authority not just for President Obama but for the next president as well.”

That is how Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell explains his support for granting the president expedited authority to negotiate trade deals and fast-track through Congress a vote those deals. The authority would apply not only to an agreement negotiated by President Obama with several Pacific partners, but to agreements made through mid-2018 and potentially through mid-2021.

McConnell recognizes, at least in this case, that a president must have enough room to perform his executive duties. The Constitution provides the president with particular powers, including the negotiation of treaties. It makes no more sense for 535 members of Congress to negotiate treaties than it does for them to micromanage other tasks that should be left to the country’s chief executive.

I would like to extend McConnell’s thought beyond treaty making. Now is the ideal time to empower both the president and Congress to better perform their assigned functions: the president to execute and Congress to legislate.

Why? First—and obviously to even the casual observer—both branches of government have been weakened extraordinarily over recent decades by the politicization of every action and the growing influence of interest groups. Many impasses in both legislation and administration arise when one party thinks that it can diminish the other by imposing roadblocks. This thought is neither new nor unique to government; when an organization’s decisionmaking boundaries are ill defined and its members cross those boundaries to seek additional power, the organization often becomes dysfunctional.

Second, less than two years away from a presidential election with an uncertain outcome, elected officials more likely recognize, as Senator McConnell does, that maintaining roadblocks deters one’s own party’s likelihood of future success as much as that of one’s opponents.

Third, the last years of a presidency seldom focus on the changes that new power brings a political party. Yet it need not be a lame-duck period. It offers the opportunity to turn to those process reforms usually neglected when the political debate centers on bigger or smaller, rather than more effective, government. President, cabinet secretary, congressional leader, and committee chair alike should be examining their power and reorganizing both internally and across jurisdictions—or, quite bluntly, they are not doing their jobs.

Behind closed doors, almost every elected official will admit that many government systems are broken. Examples abound: Medicare continually out of balance, infrastructure and highways unfunded while bridges fall apart and trains crash, the inability to pass budgets or appropriations bills, a sequester requirement that must be overridden, and much more. These are process failures, not policy failures.

How might strengthening the hands of both the president and Congress improve the likelihood of solving such problems?

Medicare provides a good example. In the last presidential election, the candidates attacked each other for trying to constrain cost growth in what both knew was an unsustainable system. Governor Romney castigated the president for cutbacks that helped expand health insurance for the nonelderly, and the president attacked the governor for favoring a voucher-like approach put forward by then–House Budget Chair Paul Ryan.

In truth, all answers to the Medicare problem involve payment constraints. The program simply has to operate within a budget. Congress won’t create a budget for Medicare, but it won’t allow the president to use his executive power to do it either. Instead Congress passes the power of appropriating money onto our doctors and us as beneficiaries.

The fix is simpler than it seems. If the Democrats favor price controls for Medicare and the Republicans favor voucher-like approaches, then set up the general rules but let whoever attains executive power use it whenever spending starts to exceed a congressionally approved limit.

This method can work well in other arenas too. Congress can set guidelines for what it wants accomplished—certainly within a budget—but then it should allow the executive branch to fulfill those guidelines. If Congress over-constrains any particular function by demanding that more be done than allowed by the budget it sets, then the executive should be empowered to make changes necessary to restore balance. This is not rocket science, it is basic management theory.

In his acclaimed book The Rule of Nobody, Philip K. Howard similarly argues that the president must have executive powers restored, to be able to avoid wasteful duplication and unnecessary bureaucracy, to expedite important public works, to refuse to spend allocated funds when circumstances change and the expenditure becomes wasteful, and to reorganize executive agencies.

When Congress limits the president on executive matters, no matter how small, it isn’t empowering itself. Instead, it entangles itself in complex and contradictory legislation, attempting to appease every interest (no matter how small), while weakening itself as it spends less and less time tackling the big issues that it is elected to address.

All this does not let recent presidents off the hook. The constant expansion in political appointees and the centralization of power in the White House over several decades has led to even more roadblocks to progress. When every decision must go through several political layers, almost no good idea can filter through to the president. When so many public statements and decisions on millions of government actions must be fed through the White House, civil servants and even top political appointees can’t function well, and they often retreat to doing nothing risky and seldom attacking limitations or failures in their own programs. Among the further consequences, many excellent government officials retreat to the private sector. Who wants to work where you are not allowed to do your job?

Whether one agrees with the examples presented here matters less than recognizing the ripeness of this time for procedural reform. Senator McConnell is right. Let’s empower the next president—and the next Congress as well.

Progress for Every Child

Posted: May 7, 2015 Filed under: Children, Columns Leave a comment »The ultimate goal of educational policy must be progress for every child. Not standards. Not attainment of grade level proficiency. Not college readiness. But progress toward developing each young person’s potential to the fullest extent possible every year. Not only is this the right educational goal, but it is the only one that pulls parents, teachers, and administrators together politically in a shared vision of helping every child, disadvantaged and advantaged alike, to grow into smarter and more capable citizens. With rare exception, each student’s progress, no matter how high or low the base level of attainment, eventually benefits others in society.

While most teachers and parents adhere to that goal, they also care deeply about their own children and protégés, and many top-down requirements ignore that legitimate and natural impulse. When my children were in school, governments and school boards devoted additional resources to the “gifted and talented.” Others felt left out. Later, the focus shifted: the schools needed to do more for “special education” students, then those for whom English was a second language (ESL). Next efforts were made to pull more students into advanced placement AP courses, then to mainstream a larger share of students with different abilities. Later, standards became the focus du jour, culminating partly in 2001 in the No Child Left Behind (NCLB) law, and more recently in new fights over the “common core” level of achievement agreed to by state officials.

The reaction? I think it can be summed up well by the story of the school superintendent who in response to No Child Left Behind essentially told his principals to focus on that group, let’s say 20% of students, with the highest probability of being brought up to the standard. As for the other 80 percent of students, those above the standard and those more likely to never achieve it, well, they implicitly had to accept relatively fewer resources if relatively more were devoted to the 20%. A more extreme reaction came to light with the “racketeering” conviction of several Atlanta school teachers and officials for feeding students answers to standardized tests and changing test sheets.

These various reform efforts didn’t necessarily fail. They responded partly to past areas of neglect. But one can also see that if each program’s success depends mainly upon shifting attention and resources, and if there are narrowly circumscribed measures of success, then it’s quite possible to come full circle on these efforts, succeed modestly with the targeted population each time, and then at the end of the day advance not at all with any one of them as the targets rotate into and out of view. To me that partly explains why our school systems have fallen behind those of many other countries.

The literature on performance measures, successful organization, and statistics gives us many lessons that need to be heeded. Among those most relevant here: no organization succeeds unless it engages in a process of continual improvement. Those who are on the ground must buy into and have ownership of the process. Tests should occasionally shift to areas that haven’t been checked. For instance, if success in math comes about because extra time to it came out of fewer recesses, one had better check on whether active students become more out of control and if obesity is increasing. Finally, it’s all right to teach to a test if we know that the test incorporates much of what we want to succeed. A great example in the school systems are the advanced placement tests, where teachers often follow a fairly rigorous but also standard way to advance a selected group of students on a subject matter eventually to be tested.

Teaching to the test is bad enough when it discourages educators from teaching necessary skills that those tests neglect. But it is even worse when state governments, school boards, or school superintendents grade a school, or principal, or teacher primarily on the percentage of students reaching some minimum standard. Such judgments ignore both other sources of knowledge and the potential progress of many students above or below the standard.

Though No Child Left Behind may have failed on some fronts, it did help set in motion more rigorous efforts to track students over many years. These tracking systems often provide the types of data by which progress can be measured along several (but, of course, far from all) useful dimensions. The potential of these data for first empowering teachers and parents with multiple measures of each student’s progress, not just attainment, has yet to be realized.

Senators Lamar Alexander and Patty Murray, chair and ranking member of the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions, have recently released a bill known as the Every Child Achieves Act. The label at least suggests a focus on every child, rather than NCLB’s focus on a subset of students who are “behind.” Many experts call the bill a step in the right direction because it tries to maintain some accountability even while allowing states much greater flexibility in setting standards.

Still, whether the states advance our still-mediocre educational system—either on their own or with the help of federal incentives—remains to be seen. A crucial telling point will be whether enough schools and jurisdictions start to recognize how to better use measures of progress, not just attainment, and then aim to develop each and every student’s potential regardless of whether they fall well below, near to, or well above any particular attainment standard.