Why Most Tax Extenders Should Not Be Permanent

Posted: April 3, 2014 Filed under: Columns, Taxes and Budget 1 Comment »This post originally appeared on TaxVox.

What to do about the tax extenders—or, as my colleague Donald Marron calls them, the “tax expirers”? Restoring the current crop (most of which expired on December 31) for 10 years would add about $900 billion to the deficit. House Ways & Means Committee Chair Dave Camp (R-MI) and Senate Finance Committee Chair Ron Wyden (D-OR) have pledged to address these extenders, though in very different ways.

Camp would take them on one by one this year, making some permanent and killing others. Wyden (and senior panel Republican Orrin Hatch of Utah) would restore nearly all of them but only through 2015.

Clearly, as my colleague Howard Gleckman suggests, we need to rigorously examine the merits of each one. But after paring out those we don’t want, should we make the rest permanent as Camp and many lawyers and accountants favor? Or should we keep them on temporarily?

Making them permanent would reduce complexity and uncertainty. But keeping them temporary would allow Congress to regularly review them on their merits. I believe that, with a few exceptions, most should not be made permanent. However, I’d extend most of them for a more than a year at a time according to the purpose they are meant to serve.

Why not make them permanent? As Professor George Yin of the University of Virginia School of Law has argued, most of these provisions really look more like spending than taxes. We must distinguish, therefore, between those items that legitimately adjust the income tax base, and those that, like direct expenditures, subsidize particular activities or persons, or respond to a temporary need.

In my forthcoming book, Dead Men Ruling, I lay out the many complications that arise when elected officials make too many subsidies permanent. Over many decades, lawmakers have effectively destroyed the very flexibility government needs to adapt to new needs and demands over time. Making the extenders permanent would tie even tighter the fiscal straightjacket we have placed on ourselves.

Fiscal reform demands retrenchment, not expansion, of the extraordinary power of permanent programs to drive up our debt and override the ability of today’s and tomorrow’s voters to make their own political choices.

Now onto a more complicated but related issue. The way Congress handles tax subsidies such as extenders should be treated similarly to the way it handles direct spending subsidies. But doing this requires addressing some tricky budget accounting problems.

Direct expenditures can be divided into two categories: mandatory spending, often called entitlements, and discretionary spending. Discretionary spending, in turn, has multiyear and single-year spending programs. Both must be appropriated occasionally. To simplify, let’s call permanent tax subsidies “tax entitlements” and tax extenders “tax appropriations.”

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) treats direct entitlements and tax entitlements similarly, projecting them perpetually into the future. If legislation enacted decades ago requires those entitlements to grow, CBO will treat that growth as part of the baseline of what the public is promised by “current law.”

But CBO does not treat direct appropriations and tax appropriations similarly. It assumes that direct appropriations will be extended either according to the program rules in effect (as in the case of most multi-year appropriations) or in aggregate (as in the case of most annual expenditures). In contrast, CBO assumes that tax extenders or tax appropriations expire at the end of each year. Continuing temporary tax extenders would be scored as adding significantly to the deficit, whereas extending many or most appropriations at current levels would not.

These inconsistent budget accounting rules mean we need to rethink how Congress treats temporary tax subsidies. If they are not going to be made into permanent tax entitlements, then, as far as practical, they should be treated closer to multiyear or annual tax appropriations. Multiyear often makes more sense for planning purposes. Of course, subsidies that are truly meant to be temporary, such as anti-recession relief, should be treated as if they end at a fixed date. The net result would be that when most “tax appropriations” other than those clearly meant to be temporary meet the end of some arbitrary extension period, CBO would no longer project their future costs at zero.

However one slices it, Congress needs to avoid making permanent or converting into entitlements even more subsidy programs, whether hidden in the tax code or not. At the same time, it must address its inconsistent budget accounting rules for direct appropriations and those extenders that are really little more than appropriations made by the tax-writing committees.

A Camp-ground for Tax Reform

Posted: March 6, 2014 Filed under: Columns, Taxes and Budget 3 Comments »This post originally appeared on TaxVox, the Tax Policy Center blog.

By proposing a far-reaching and detailed rewrite of the Revenue Code, House Ways and Means Committee Chair Dave Camp (R-MI) did something very few elected officials have done in recent years: He stuck out his neck and proposed radical reform. The initial press response has focused on politics and concluded that neither Republicans nor Democrats will be able to take on the special interests, that there is too much partisan gridlock, and that the plan is going nowhere.

But such responses largely ignore the history of successful reforms and forget that some policymakers do care about policy. If the goal is to conquer a mountain, someone has to start by building a common basecamp.

Almost any major systemic reform that does more than give away money creates losers. Someone always has to pay for whatever new use of resources the reform seeks—in this case, tax rate reduction and a leaner code with fewer complications. But politicians hate identifying losers. We voters punish them for their candor, which is why they nearly always increase deficits to achieve their goals and leave it to a future Congress to identify the losers who pay the bill.

With his full-blown tax reform proposal, Chairman Camp decided to lead and proposed repealing many popular tax breaks. There’s a lot I like and some things I don’t like in his proposal, but the simple fact is that a well-designed comprehensive alternative to current law can change the burden of proof. Change a few items, and each interest group argues that it was unfairly picked on. Put forward an alternative that takes on almost all preferences, and each interest then needs to justify why it deserves special treatment not accorded others.

The prospect for any reform is nil if no leaders do what Camp did and step up to the plate. The process is not one of instant epiphany. Rather it slowly builds support. Those who first propose change may increase the odds of success from 5 percent to 10 percent. Others who follow further improve those odds. If we reject out of hand all ideas that start with less than a 50 percent chance of success, we’d probably never reform anything.

It often takes modest support by others to move the process forward. In 1985, President Reagan and House Ways & Means Committee chair Dan Rostenkowski started the legislative process that yielded the Tax Reform Act of 1986 by simply agreeing not to criticize each other while the measure went through committee. Like Speaker Boehner today, Speaker O’Neill wasn’t enthusiastic about reform then, but Rostenkowski was able to proceed anyway.

In 1985, Rostenkowski knew he could pass a Democratic bill. But he knew it would go next to the GOP-controlled Senate Finance Committee. Each party would have a turn and a final agreement would come from a bipartisan conference committee. If House GOP leaders let Camp mark-up his bill now, Democrats would have their turn, at least this year, in the Senate. At least so far, both President Obama and senior Ways & Means Democrat Sandy Levin (D-MI) have avoided any major criticism of Camp’s plan, but one wonders if Democrats aren’t going to forego an opportunity, once again joining Republicans in deciding in advance that nothing substantial can be done, so it won’t.

Leadership is seldom about achieving results that can be predicted with certainly. More often it requires using your clout to change the process or reframe the debate in ways more likely to serve the public. It’s certainly about more than protecting your party’s incumbents in the next election regardless of the policy consequences.

When I served as economic coordinator and original organizer of the 1984 Treasury study that led to the ’86 Act, it was a time when books declared major tax reform the “impossible dream.” Sound familiar? In the face of that dispiriting commentary, I tried to encourage the Treasury staff with what I call the “hopper theory” of democracy: the more good things you put in the hopper, the more good things are likely to come out. By this reckoning, Chairman Camp has already won.

Can the Modern Politician Call Us to “Place Our Collective Shoulder to the Wheel”?

Posted: February 5, 2014 Filed under: Columns 4 Comments »Whom do we remember as our greatest presidents? Often, the ones who call us to act on a higher plane, to be more than we have been. Some leaders stand out in every list: Washington, who led us through a treacherous beginning; Lincoln, who saved the nation; and FDR, who led us against perhaps the most evil axis of nations in history. But let’s add others: Truman, with his leadership on the Marshall Plan and postwar communist containment; and Jefferson, with the purchase of the Louisiana Territory.

Similarly, when we think about which rhetoric inspires us, we don’t usually quote the language used to back the latest farm bill or tax break. Ever undergo the emotional transition at the Lincoln memorial from feeling touristy and tepid outside this behemoth boulder building, to turning teary as you read the second inaugural address? You may not have noticed, but one line in that address mentions a new government program:

Let us strive on to finish the work we are in, to bind up the nation’s wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan, to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations.

Did you find it? Look again at how it’s worded. Lincoln didn’t promise that he would do something for widows and orphans; he called us to add that task to the many sacrifices we still needed to make.

Now consider President Obama’s State of the Union address. I don’t mean to pick on it, as it largely followed the format to which for several decades we have become accustomed. Its emotional high point wasn’t when he listed all his proposals but, at the end, when he extolled the sacrifices of Army Ranger Cory Remsburg.

Men and women like Cory remind us that America has never come easy. Our freedom, our democracy, has never been easy. Sometimes we stumble; we make mistakes; we get frustrated or discouraged. But for more than two hundred years, we have put those things aside and placed our collective shoulder to the wheel of progress—to create and build and expand the possibilities of individual achievement; to free other nations from tyranny and fear; to promote justice, and fairness, and equality under the law, so that the words set to paper by our founders are made real for every citizen.

Remsburg, by the way, was on this tenth tour of duty in Afghanistan and Iraq, when his life underwent dramatic upheaval.

Now consider what the president and his Republican counterparts, in their follow-up addresses, ask of us. For the most part, to accept more goodies: more benefits or fewer taxes somehow paid for by someone else. Fortunately, they tell us, we don’t have to put our shoulder to the wheel of progress; we only need to move aside others who block it from rolling forward.

Therein lies a great tragedy of politics and one of the greatest threats to the functioning of democratic government: politicians’ need to tell us about all the great things they will do for us, usually combined with their plodding efforts to tell us that the source of our nation’s problems is those who don’t agree with us. And the great focus they place on “I,” as in I—not you, not we—am going to make all these good things happen. Try to find “I” in Lincoln’s great addresses.

Yes, I recognize that few politicians can win elections without playing this game. Still, I don’t find myself inspired by the tax cuts or extra government benefits I might receive. I’m not moved by the call for others to sacrifice for me. I’m not motivated to do more for posterity by contemplating what you should be doing.

I’m not suggesting that sacrifice has merit in and of itself. When we make such efforts, we do so because we expect that society will benefit in the long run. But not now, when we must give up our time or energy or resources at building that better world. And not necessarily us.

One of the most popular Old Testament verses, sung and read repeatedly in churches and synagogues, comes from the most quoted of all of the Hebrew prophets:

Then I heard the voice of the Lord saying, “Whom shall I send? And who will go for us?” And I said, “Here am I. Send me!” (Isaiah 6:8).

Even if we continually vote out of office any politician who asks us to sacrifice something to make the world a bit better off, we still want to be called. We want collectively to put our shoulder to the wheel. Thanks, Cory. I hope I have half the courage in dealing with these mundane issues that you display in dealing with life and death.

Finding an Opportune Way to Expand the Earned Income Tax Credit

Posted: January 30, 2014 Filed under: Columns, Income and Wealth, Job Market and Labor Force, Taxes and Budget 5 Comments »President Obama announced only one major new proposal during last night’s State of the Union address. Here’s what he said:

I agree with Republicans like Senator Rubio that it [the EITC] doesn’t do enough for single workers who don’t have kids. So let’s work together to strengthen the credit, reward work, and help more Americans get ahead.

Having worked on the EITC and other wage subsidies for a long time (and having introduced them at a crucial stage of tax reform efforts in the 1980s), I say it’s about time they were back on the table. Particularly since the onset of the Great Recession, policy discussions around helping those with lower incomes have focused on unemployment insurance, food stamps, and government-subsidized health insurance. Employment needs to move toward the front of our public policy agenda.

As necessary as these other social safety net programs might be—and am not trying to assess their merit here—they generally do not encourage people to stay in the workforce. Like the welfare of old, before the onset of reform of what then was Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC), they provide the greatest benefit to those who do not work at all. While it’s debatable whether a simple EITC expansion increases total labor supply, there is almost no doubt that per dollar of cost it increases employment more than many other social welfare provisions.

Employment has been a vexing and growing challenge for the American economy. The share of all adults who work—also called the employment rate— was declining even before the Great Recession, particularly among the young and the near-elderly. Indeed, a declining employment rate represents a far bigger and longer-term issue than unemployment, since the NON-employment rate includes both those who are unemployed and those who drop out of or never join the labor force.

Concern over employment makes wage subsidies fertile ground for bipartisan consensus, if—and this is a big “if” in these partisan times—both sides can claim victory from the deal.

Consider the history the EITC. Almost every president since Richard Nixon has signed legislation establishing the EITC, expanding it, or making some provisions permanent. And it’s been bipartisan. The initial enactment and the largest increases all occurred under Republicans—Ford, Reagan, and George H.W. Bush, while the expansion during the Democratic Clinton administration was also quite significant.

Many who backed these legislative changes did not view the credit in isolation. They often favored it over some alternative—welfare for Senator Russell Long (the EITC’s first champion) and a minimum wage increase for President George H.W. Bush. Or they accepted the EITC as part of a broader tax or budget package. The EITC was never the subject of stand-alone legislative action.

That leads us to today, and what compromises might be supported by both political parties. I suggest two possibilities.

One, following our historical pattern, is to expand the EITC as an alternative to other efforts. At some point, recession-led unemployment insurance expansions will end. A bill to increase the minimum wage might go nowhere. Might an expanded wage subsidy be a compromise? A broader tax or budget bill always presents possibilities. The EITC offers one way to mitigate the net impact on lower-income populations, whether offsetting losses from new deficit reduction efforts, or ongoing cutbacks due to sequestration or dwindling appropriations.

The other is to tweak the EITC so it interacts better with other policy goals, such as reductions in marriage penalties—a cause often advocated by Republicans. The childless single workers identified by the president are not the only ones left out of any significant wage support. So also are many low-income married workers. Despite recent changes, the EITC still creates marriage penalties, particularly if a low-wage worker marries into a household already receiving the maximum credit. Such a low-wage worker often fares worse than a single person who gets nothing or almost nothing: once added to the household, the additional worker’s income can phase out his partner’s’ EITC benefits and reduce or eliminate any previous eligibility for other public benefits. Current government policy announces that it is more advantageous to stay unmarried.

Simply expand the current, very small, credit for childless single people, and marriage penalties would multiply in spades. I suggest including in any expansion low-wage workers who decide to marry or stay married, not only those single persons left out. Such an expansion would proceed largely along the same lines as the president’s, but also reduce marriage penalties .

In sum, the president’s best path to bipartisan support for the EITC is to stress more policies that favor employment, offer the expansion as a compromise from other efforts less favored by his opposition, and reduce marriage penalties.

What Should We Require From Large Businesses?

Posted: December 6, 2013 Filed under: Columns, Income and Wealth, Taxes and Budget 3 Comments »If we want successful companies to contribute to the economy fairly, what should we be asking them for? More corporate income tax? A higher minimum wage? Health insurance for employees? More profit-sharing for employees? Restricted-stock payments of highly paid executives, so they can’t succeed individually when they fail their workers and shareholders?

We’ve tried all these approaches, but at different times and in a discombobulated way.

The corporate income tax, which once raised far more revenue than the individual income tax, now applies mainly to multinational companies, which find ways to hide their income in low-tax countries. Domestic firms often avoid the tax altogether through partnerships or similar organizational structures.

The minimum wage has been allowed to erode substantially. I earned $1.25 an hour while in high school in the mid-1960s; if that amount had grown at the same rate as per capita personal income, high school kids and others would now be earning $20 instead of $7.25.

Health insurance mandates for many employers is our new form of minimum wage. The ACA’s $2,000-per-employee penalty for larger employers that do not provide insurance is essentially an additional “minimum wage” requirement of at least $10 an hour, either in the form of a penalty or health insurance.

Profit sharing was at one time touted as the way to instill better work habits and allow employees to share in a firm’s success. Many employees, however, put all their savings in that one investment and got stuck with huge losses when their firms declined.

A 1993 Tax Act limited to $1 million annually the amount of cash and similar compensation that could be paid to top executives and still get a corporate tax deduction. Post-reform, stock options flourished, as did a more uneven distribution of income within firms.

More recent proposals to reform the corporate income tax set minimum taxes on multinational companies, regardless of the country in which the income was earned; increase the minimum wage on all firms; bump up or reducing the mandate on larger employers to provide health insurance (by adjusting either what services the insurance must provide or the size of the penalty for not providing insurance); regulate companies to disclose how unequal their compensation packages are; and require executives, particularly in financial companies, to invest more in the stocks and bonds that couldn’t be sold immediately and would fall in value should their companies falter.

What drives all these proposals, I think, is the notion that large organizations only become that way by being successful and that they owe the public something in return for this success. At some point, almost all companies achieve their size by generating above-average profits and sales growth. The Wal-Marts and Apples and Mercks of today, the General Motors and U.S. Steels and Pennsylvania Railroads of yesterday, have or had more power and money than most. Did they get there only through the hard work and ingenuity of a few people who deserve most of the rewards? Or were they also lucky? The first out of the block? The beneficiaries of scale economies, where only a few companies would survive or the winner would take all? Did they get government help along the way, perhaps taking advantage of the basic research that served as a prelude to their development? Or the protections of a developed legal system, along with a bankruptcy law that limited their losses? If so, doesn’t that legitimize the discussion of how their gains might be shared, either with their own employees or the public?

If we truly want to create a 21st century agenda, I wonder if we could come up with better, more efficient, and fairer policies by asking the broader question than by piecemeal approaches. The corporate income tax, for instance, has been put forward by the chairs of the congressional tax-writing committees, as well as the president, as a ripe candidate for reform. Yet, however much I might favor such reform as a pure tax issue, it’s only a piece of these broader redistributional questions. Might it be better, for instance, to abandon the attempt to assess any extra layer of corporate income tax, and instead ask larger firms to take a greater role in accepting apprentices, hiring workers during a downturn, sharing profits with workers, providing minimum levels of compensation but not necessarily all in health insurance, and restricting the ability of their higher-paid managers to walk away with bundles even while their firms fail?

Obviously, the devil is in the details. But we should at least have the conversation.

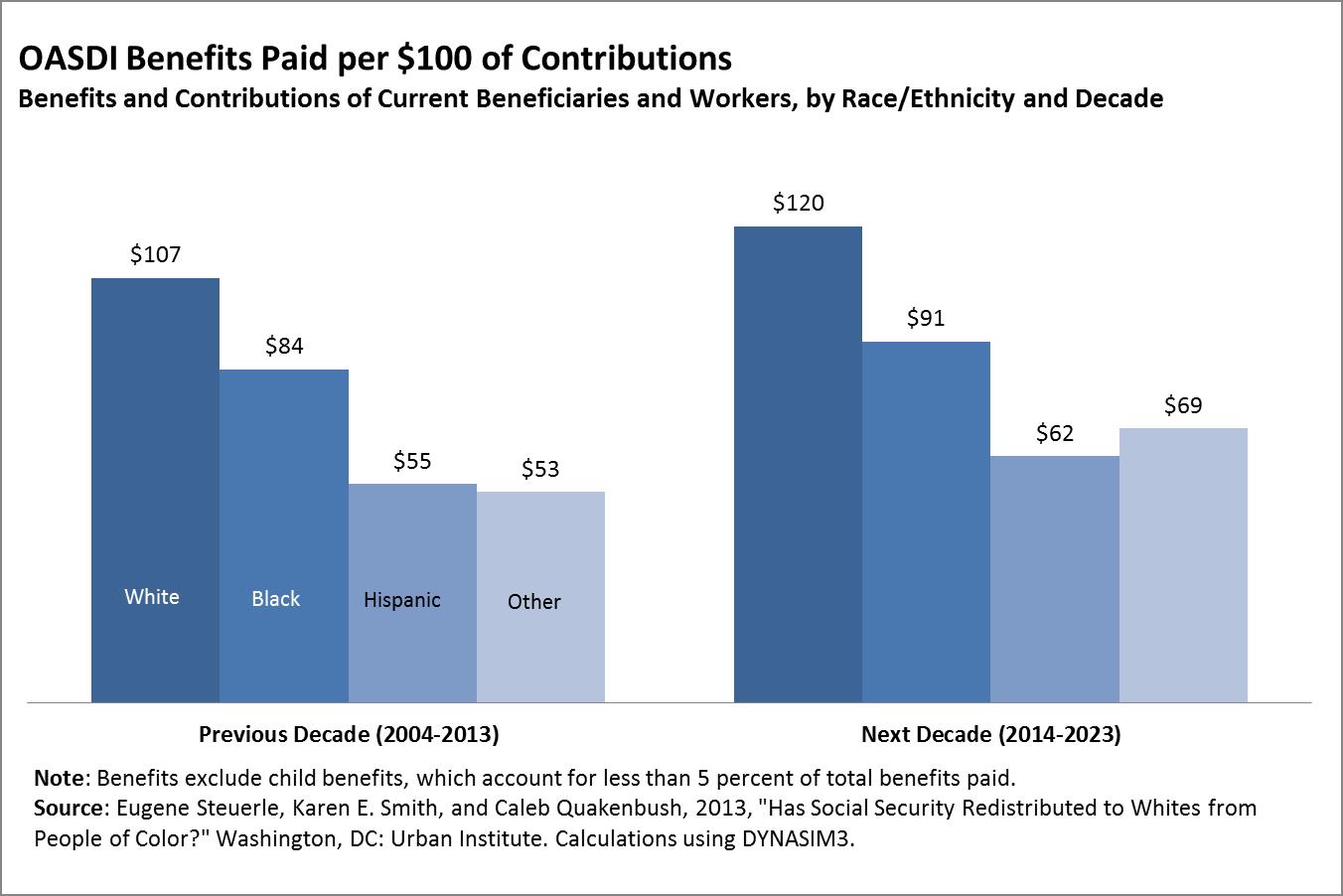

Has Social Security Redistributed to Whites from People of Color?

Posted: November 8, 2013 Filed under: Columns, Income and Wealth, Race, Ethnicity, and Gender 6 Comments »In a new brief, my colleagues and I examine how many features of Social Security combine to redistribute money among racial and ethnic groups over long periods of time, combining together generations. We find that the program as a whole, and especially its retirement portion, has likely redistributed from blacks, Hispanics, and other racial minorities to whites.

The major cause? When taxes are compared to benefits for each generation, the early generations of retirees got large windfalls, those retiring today come closer to breaking even, and tomorrow’s retirees on average will get back less than they pay in, assuming some modest interest rate could have been earned on their contributions or taxes. This phenomenon by itself wouldn’t cause interracial redistribution, but whites disproportionately occupy the high-return generations, while Hispanics, more recently immigrated groups, and blacks increasingly occupy the lower return generations.

The immigration part of the story is easy to understand. Hispanics and other recent immigrants weren’t around to receive the windfalls that came about as the system expanded over its early decades. Whenever Congress increased lifetime benefits for retirees and near-retirees, younger workers would be required to contribute for decades to support those higher benefits. Older workers would get those higher benefits with fewer years of additional contributions or, at times, none at all.

As for the redistribution from blacks, they disproportionately occupy the lower-return generations because of their larger family sizes. A simple analogy might be made with a two-family world where one couple has three kids and the second has one, but the kids all contribute the same $1,000 each to support the four parents, who all get the same benefit of $1,000 each. The larger family contributes $3,000 and gets back $2,000. The effect will be permanent unless some other redistributions over time offset this windfall gain for the smaller family.

Of course, these simple stories ignore Social Security’s other moving parts. Its progressive benefit formula, which I consider in many ways brilliant because it is based on lifetime rather than annual earnings, redistributes to those with lower lifetime earnings. At the same time, Social Security contains many regressive features. For instance, as a protection for old age it appropriately requires that payments be made in the form of annuities, but that ends up redistributing to those with higher incomes because they have higher-than-average life expectancies. Also, unlike private pensions where it would be illegal, single heads of household, often lower-income women, are required to contribute for spousal and survivor benefits they can’t receive.

Because of these various offsetting features, the retirement or old-age part of the system exhibits little net progressivity even before adding on this new multigenerational consequence of making each successive generation pay more for each dollar of benefit it receives.

When disability insurance is considered, it adds to significantly to progressivity in the sense of redistributing to those with lower incomes. From a broader perspective, of course, one can hardly consider it a plus that some racial and ethnic groups incur higher levels of disability, along with the huge losses of private income that Social Security does not replace.

The study does not contain policy prescriptions, though my own separate work has for very long time suggested the merits of substantively (not just symbolically) higher levels of minimum benefits and other progressive adjustments. Nor does the study contradict the success of Social Security in reducing poverty dramatically among the elderly, particularly in its early decades. It does suggest that as reform is being considered, we give serious attention to whether the system achieves its stated objectives, including the extent to which it really provides better protection for those individuals and classes who are less well off.

Both the left and right, I think it fair to say, have presumed that the system is far more progressive than it turns out to be—a more recent literature finding to which this study adds. Unfortunately, the Social Security debate, like so many we have today, tends to be argued on a thumbs-up or thumbs-down basis, rather than on how it might be better designed to meet society’s objectives.

Read more on Economix and Wonkblog.

Sixteen Days in January: A Story of the Next Shutdown

Posted: October 16, 2013 Filed under: Columns, Taxes and Budget 4 Comments »Dateline: January 2014. Federal government shuts down completely.

Day 1. Mall, Washington, DC. Park Police decide shutdown again requires barring access to war memorials and the grounds of the Washington, Lincoln, and Jefferson monuments. Veterans rise up in anger and push back barricades. “If you’re furloughed, how can you keep us from entering the parks?” asks Joe Laploski, an Iraqi veteran from New Rochelle, NY. Park Police assign unpaid legal interns to determine whether Park Police should arrest themselves for working.

Day 2. White House. In hastily called press conference, President Obama announces major plan to deal with the national emergency. Enforcement on malls will be sustained, lest someone fall in the Tidal Basin and sue the government. Government debt will thereby be reduced, since Park Police cost less than those future lawsuits, at least on an expected basis.

Day 3. Capitol. Lights go out. Speaker Boehner lost underground. Democrats offer to fund search party, but, invoking the Hastert rule (requiring agreement by a majority of the majority party to act) and unable to decide whether they want to find him, Tea Party refuses.

Day 4. Longworth House Office Building. Democrats send search party after Boehner anyway. Find flasks of aged whiskey hidden by the late former Ways and Means Committee Chair Wilbur Mills two levels below the committee room where he presided. Debate ensues over whether imbibing is an essential government function. Inspired by former Occupy Wall Street supporters, Democrats decide to represent the activity as unity with the “99 percent,” who normally can’t afford such expensive booze.

Day 5. Treasury Department. Electronic payments of billions of government checks and bills stop. Secretary Lew called to emergency meeting at the White House to determine how much blame to assign to Republicans.

Day 6. Oklahoma City. Local Tea Party members claim the IRS is targeting them, citing delayed refund checks as proof. Back in Washington, House Oversight and Government Reform Committee decides to hold hearings in the dark.

Day 7. Near Capitol. Republican staffers gather at a local bar to debate how to get work done during the impasse. Consider asking the guy in charge of the lights for help, until they discover that position no longer exists because of the sequester. Boehner still missing.

Day 8. White House. President Obama plans national address during primetime. He asks the Democratic Party to pay for the speechwriters. Local TV stations refuse to broadcast the president’s speech unless their invoices for airing “Army Strong” recruiting commercials are paid.

Day 9. Treasury Department. Secretary Lew tries to issue checks to TV stations. In a 5-4 decision, the Supreme Court bars him from doing so until he lays out the precise legal priority for billions of unpaid bills.

Day 10. Princeton, NJ. Despite the worldwide recession induced by the shutdown, foreigners still flock to outstanding US obligations, and interest rates on US government securities tumble instead of rise. In a New York Times op-ed, Paul Krugman argues that at this low rate we should borrow all we can—unless it would pay for a Republican tax cut.

Day 11. Treasury Department. In response to the House Oversight Committee’s hearings, Treasury’s Inspector General issues report that Republicans were indeed targeted, indicating as proof that their delayed refund checks were bigger on average than those for Democrats. However, no crime was committed, he asserts.

Day 12. White House. President issues a statement that IRS targeting of Republicans is inexcusable. Fires top IRS data processing personnel and replaces commissioner with top executive from Avon Products with an unblemished record in taxes and data processing because she has never worked in either field.

Day 13. Sacramento. Governor Brown announces that millions of Californians are now insured under Obamacare. He asks that no penalties be assessed on those getting thousands of dollars in excess benefits since recordkeeping was impossible. On Meet the Press, Senator Cruz expresses amazement that the shutdown he favored affects every government program but Obamacare.

Day 14. White House. President Obama launches new peace initiative. He asks Hassan Rouhani of Iran and Bashar al-Assad of Syria to hire their own nuclear and chemical weapons inspectors, claiming that the U.S. shouldn’t have to pay to clean up other countries’ messes. President Putin offers to mediate and contribute Russian oil revenues.

Day 15. Capitol. Boehner found. Claims, like always, he knew exactly where he stood. Negotiates agreement with president on a continuing resolution to fund government until after congressional elections. Congress then shuts itself down until December 2014.

Day 16. Russell Senate Office Building. Before departing, Chairman Camp of the Ways and Means Committee and Chairman Baucus of the Senate Finance Committee issue a 6,700-page document with complex details on how to structure a major tax reform. Congressional leaders promise to take up issue immediately…in the next Congress.

Is it Unfair to Exclude the Poor from Government Subsidies?

Posted: September 20, 2013 Filed under: Columns, Income and Wealth 13 Comments »Advocates for many social policies—health care insurance, asset development for the poor, charitable deductions for those currently ineligible, child care subsidies, and countless others—often base their arguments on distributional grounds. Typically, lower-income households cannot avail themselves of these benefits or subsidies, and advocates deride the unfairness of it all.

We must be very careful when framing the issue this way. True, many incentives apply disproportionately and inappropriately to higher-income individuals. However, extending these incentives to those with lower incomes does not, by itself, create better policy or even increase fairness.

Put simply, if Congress grants additional incentives to low- and moderate-income households, it decides simultaneously to distribute more to them and to distribute it through a particular subsidy or incentive—and, in the case of incentives, that the benefit should go only to those who opt to use it. Each of these choices, not just any one of them, must be justified in its own right.

Take health insurance under the Affordable Care Act. This legislation offers some lower-income households subsidies of nearly $20,000 and some middle-income households subsidies of $10,000. These households must, however, use this subsidy to buy health insurance, not more education or food or transportation. Those who don’t buy health insurance get none of this subsidy, even if they are poor.

Another aspect of this legislation imposes a minimum burden on many employers who do not purchase health insurance of $2,000 per full-time worker. That’s equivalent to increasing the minimum wage by about $1.25 an hour for someone who works 1,600 hours a year. But, the mandate is to pay the government that money or give employees health insurance. The mandate cannot be met by bumping up the employee’s cash earnings by an equivalent amount.

In effect, we must distinguish between the distribution of benefits or taxes and their allocation or efficiency. Even if we conclude that it would be fairer to give more benefits to those with lower incomes, it does not follow that any benefit they receive is the best use of that money. If a housing ownership subsidy, a housing rental subsidy, and handing out money have the same overall distributional consequence and cost, we still need to decide which, if any, of these options is most effective use of that money.

To give another example, over many years Congress increased the standard deduction in the tax system in order to help lower- and middle-income taxpayers. The standard deduction was higher than what most households would get if they itemized available deductions—in 2013, a $12,200 standard deduction for a couple is far more valuable than $6,000 in mortgage interest and charitable deductions. Increasing the standard deduction increased progressivity, even while it reduced the share of homeownership and charitable deduction benefits received by those with lower incomes. One can hardly say these increases were “unfair.”

Proposals to provide various benefits or incentives to lower-income households, as opposed to simply giving them more money or providing other benefits, must rest on some grounds other than progressivity. Some work and saving policies that give a “hand up” rather than a “hand out” might provide better incentives for work and saving, with side benefits to the rest of society. More asset-development incentives at lower income levels might create more democratic ownership of wealth, enhance retirement security more optimally, or grant extra benefits to society when homeowners take better care of their living quarters than renters. Requirements to spend subsidies on health insurance may reduce the number of people able to game the system by seeking free care when they get sick and avoid any contribution to the cost of their health care. Many of these choices are not easily assessed quantitatively, but they are primarily efficiency arguments, not fairness arguments.

At the same time, we still want to look at the distribution of any benefit to see just who receives it and how any program allocates its monies. For instance, if homeownership creates positive gains for society, might it not be better to spend the same amount of money to encourage homeownership among all income classes than to spend disproportionate amounts on those buying second homes or McMansions? Looking at distributional results helps us make such judgments by assessing the actual rather than intended impact of the policy.