Extending the Charitable Deduction Deadline to Tax Day

Posted: March 19, 2013 Filed under: Nonprofits and Philanthropy, Shorts, Taxes and Budget 2 Comments »Extending the charitable deduction deadline is a move with precedent: the government has used it to encourage giving following a natural disaster. President Barak Obama signed a provision allowing charitable donations toward the Haiti earthquake made from January 11 to March 1, 2010, to be deducted on 2009 tax returns. President George W. Bush signed a similar law allowing donations for tsunami relief made through January 31, 2005, to be deducted in 2004.

These provisions aim to increase giving at a time when need is critical. In reality, such temporary laws have limited effect because many do not know about these one-off incentives.

Consider instead the marketing possibilities of more permanent incentives to allow charitable deductions made by April 15, aka tax day, to be applied to the previous year’s tax returns.

By making what has frequently been a temporary measure into a permanent law, you eliminate the problem of trying to publicize brief windows of opportunity. Instead, people would come to expect that at filing time they would consider how much they would save by giving to charity.

Evidence suggests that, as in other facets of life, people are prone to making their decisions concerning giving at the last minute. The Online Giving Study finds that 22 percent of online donations are made on the last two days of the December, the last possible moment to claim a tax deduction for that year. Presumably this effect could be magnified if taxpayers were able to add to their charitable giving up until the last two days before they filed their tax returns.

Think of what such tax software companies as TurboTax or H&R Block could do by showing taxpayers directly how donating an extra $100 or $1,000 to any charity would lower their taxable income. The companies could even process the donation immediately through a credit card. If such a measure were enacted, I predict some foundations and charitable-sector collaborative organizations would immediately engage software tax preparation companies, other tax preparers, banks, and online giving organizations to figure out the best way to market this opportunity to the public.

This incentive would be by far among the most effective that Congress has ever provided in almost any arena, including existing charitable incentives. Why? Essentially, the revenue loss to the government is only 30 cents or so (the tax saving) for every additional dollar of charity generated. If people don’t give more, there are no losses, outside some slight timing differences. This is triple or more the estimated effectiveness of charitable giving incentives overall.

Marketing experts immediately grasp windows of opportunity. Back-to-school sales take place in September when families are thinking about school, grocery store advertisements near the weekend when more people do their shopping, Caribbean cruises in the winter when people are cold. The very best time to advertise charitable tax saving is when people file their tax returns.

This change would also add an element of certainty. Not knowing their income and tax rates for the existing year until it is over, people can only guess at the tax effect of any contribution they make to charity. When filing taxes, they can calculate exactly how much tax an additional donation would save.

A permanent law would also encourage all areas of giving instead of only the specific causes picked by Congress. Such targeted opportunities don’t necessarily increase people’s total donations: people are more likely to switch which charity they give to, not give more overall, when Congress highlights a particular charity.

In exploring this option for a number of years, I can find only one significant concern: the increased complication that is always induced by offering people choices (the actual tax-saving calculation, as noted, is actually simpler for many). Would people, for instance, mistakenly report their contributions twice, once for the past year and once for the current year? Would charities have trouble handling an extra checkbox in which taxpayers indicate in what year the contribution was intended?

If one is really interested in making the incentive better, this complication obstacle is easy to overcome. There are options here.

One would be to improve information reporting to IRS on charitable gifts. Only gifts for which charities give formal statements to individuals and the IRS itself could be made eligible. Noncash gifts might be limited in this case to those for which a formal valuation is provided to the taxpayers or, at least initially, excluded altogether. The information reports might only apply to those contributions over $250 for which charities are already required to provide statements to individuals. If charities don’t want to participate, they don’t have to.

Another, lesser bargain would be to experiment first only with online contributions for which software companies could send a report to the individual, charity, and IRS alike (this could include online checks for those banks and other institutions, not just credit card companies, who would be willing to participate). Other compromises along these lines are possible, and some of them on net are likely to improve compliance because of the integrated information system—a win-win strategy.

In separate testimony, I have offered a number of ways that this type of proposal could be incorporated into broader tax and budget reform so charitable giving is increased without any loss in revenues to the government.

With the United States still locked in a recession and the government cutting back its own efforts, what better time is there to encourage greater charitable giving?

Creative Ways Around a Blunt Sequester

Posted: February 27, 2013 Filed under: Columns, Income and Wealth, Taxes and Budget 5 Comments »I would like to offer two simple plans, one for Republicans and one for Democrats, to avoid a blunt, across-the-board sequester with no realistic assessment of priorities. Each plan gives both parties something they want without abandoning their core principles. Each also strengthens the party making the proposal by putting the other one on the spot if it fails to move toward a moderate compromise.

First, Republicans. They should offer to empower the president, within fairly broad limits, to reallocate the direct spending cuts required by sequester and include entitlements in the offer. Yes, they would cede some power over a relatively moderate share of total spending, but they would retain their primary goal: forcing Democrats to tackle the spending side of the budget.

Next, Democrats. They should replace their demand that the sequester include tax increases with a simpler demand that the rich pay a fair share of any burden. Yes, they would give up their requirement of balancing tax increases with spending cuts, but they would retain their more basic goal: maintaining or enhancing progressivity.

To understand why these strategies would work, we have to go back to the root causes of the impasse. Both parties are fiercely fighting to compel the other one to ask the middle class for the inevitable—to give up something, at least long term, to restore reasonable balance to the budget. Each party considers it political suicide to take the lead itself. Just think back to the presidential campaign, when each candidate indicated support for Medicare cuts, only to be viciously attacked by the other.

At the same time, both parties feel trapped and confused by years of mutual dissembling about subsidies that are put into the tax code.

Given that the American Tax Relief Act increased tax rates just last month, neither party is suggesting higher taxes. The debate now is over the tax base. Republican, Democratic, and independent economists all agree that subsidies in the tax code can be made to look just like direct spending. Therefore, any reasonable debate should be over whether all subsidies and spending programs work well and are worth every dime they cost, or whether they should be reformed—not on which side of the ledger they sit.

For Republicans, the subtext is that direct spending also needs to be tackled, and much of that direct spending lies in so-called mandatory or entitlement spending, which occurs automatically with no new vote required by Congress. The push to enact yet more “tax increases,” just after tax rate were raised, they consider unfair and imbalanced.

For Democrats, the subtext is that the rich have made out quite well in recent decades, so they should bear a significant portion of any deficit reduction. Excluding tax subsidies, which tend to be a bit more top-heavy and favor taxpayers with above-average incomes, they consider unfair and imbalanced.

As I noted, to an economist of any stripe, deciding which programs to fix according to the label we place on them—direct spending or tax subsidy—is silly. But this logic belies a long history where both Democrats and Republicans were quite happy increasing tax subsidies since they could then claim smaller government (through lower taxes) when they were actually increasing the scope of government activity (through more interference, along with deficits or higher tax rates to support the subsidies). Now that we have to cut back on automatic growth in direct spending, or tax subsidies, or (most likely) both, it’s harder to change the terms of the debate.

In truth, Republicans should be just as happy cutting back on tax subsidies as on direct spending, as both mean less government interference in the economy. By the same token, Democrats should be just as happy with direct spending cuts as with cuts in tax subsidies. Since Democrats, too, end up with smaller government either way, they should focus on progressivity, not the more semantic debate over cuts in tax subsidies versus direct subsidies.

That’s where my compromise proposals come in. If Republicans would simply empower the president to reallocate the spending cuts, then the bluntness of the sequester would be eliminated. Yes, they would be giving up some power, but come on, they control only one house of Congress. Look how they came out of the last debate, with only tax rate increases and a bloody nose to boot. Forcing the president to choose also enables Republicans to run later on how they would have chosen better. And if the president really cares about progressivity, he should want to extend those cuts to entitlements, many of which also provide more benefits to the rich than the poor.

As for Democrats, why not aim their sights at their real target: progressivity? If the Republicans would allocate spending cuts as progressively as the Democrats could ever expect tax base increases to come out, then they, too, will have achieved their principal objective. Moreover, if Republicans couldn’t balance the burden of deficit reduction with spending cuts alone, they would be forced to admit that they have to go to the tax code to search for additional options, including tax subsidies.

A similar type of compromise might also be used to change the timing of the sequester, an issue beyond the scope of this brief column.

Simply put, to move beyond budgetary impasses, each party must figure out what it can give up to get what it really wants, while putting the other party on the spot for not responding to a reasonable offer of compromise. Neither of my suggestions is perfect, by any means, but I think either one or both could remove the bluntness of the sequestration.

Education Presidents And Governors: Ain’t Gonna Happen

Posted: February 20, 2013 Filed under: Children, Columns, Taxes and Budget 24 Comments »In last week’s State of the Union speech, President Obama put great emphasis on expanding early childhood education. He’s not alone in recognizing the vital role of education as the launching pad for 21st century growth. George W. Bush wanted to be known as the “education president,” and so did his father, George H.W. Bush.

Many governors have similar aspirations. Jerry Brown, for instance, has gotten headlines for his efforts to restore the California university system to its former high status. State support for higher education has fallen dramatically there, particularly as a share of the budget and of Californians’ incomes but also in real terms. Brown even supported a tax increase to try to reverse this trend.

While I strongly support these types of effort, right now pro-education governors and the president are fighting a losing battle. Their new initiatives merely slow down their retreat against a health cost juggernaut.

California isn’t much different from many other states. The college bound and their parents witness this declining state support in the form of ever-rising costs and student debt. Less recognized is the fall in academic rankings of the nation’s leading public universities, such as many of the formerly extolled California universities and my own alma mater, the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

State support of education hasn’t just declined at postsecondary schools. In recent years, legislators have assigned K–12 education smaller shares of state budgets as well. During the recession, teachers were laid off and not replaced in many states. Efforts to expand early childhood education have also stalled, although the president’s initiative may give it some temporary momentum.

Federal spending policies only reinforce the longer-term anti-education trend. An annual Urban Institute study on the children’s budget suggests future continual declines in total federal support for education as long as current policies and laws hold up.

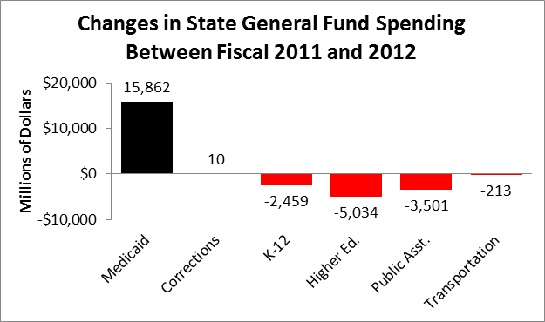

Education spending will continue to decline as long as health costs keep rising rapidly and eating up so much of the additional government revenues that accompany economic growth. The figure below, prepared by National Governors Association (NGA) Executive Director Dan Crippen and presented by his deputy, Barry Anderson, at a recent National Academy of Social Insurance conference, tells much of the state story: health costs essentially squeeze out almost everything else.

Fiscal 2011 data based on enacted budgets; fiscal 2012 data based on governor’s proposed budgets

Source: National Association of State Budget Officers, as presented by Dan Crippen, National Governors Association

These rising health costs don’t just place a squeeze on government budgets; they also are one source of the paltry growth in median household cash income over recent decades.

Within states, health costs show up primarily in the Medicaid budget. As the NGA numbers demonstrate, recent federal health reform did little and is expected to do little to control these state costs, despite large, mainly federally financed subsidies for expanding the number of people eligible for benefits.

With populations aging, state and federal governments now also face demographic pressures to increase their health budgets. Large shares of the Medicaid budget go for long-term and similar support for the elderly and the disabled. This budgetary threat also extends to revenues as larger shares of the population retire, earn less, and pay fewer taxes.

The next time someone tells you that we should wait another ten years to control health costs because we’ll be so much smarter and less partisan then, remind him or her that this procrastinating implicitly advocates further zeroing out state and federal spending on education—and the children’s budget more generally. Presidents and governors will never succeed with their education initiatives until they stop the health cost juggernaut in its tracks.

Video on the Ways and Means Committee’s Hearing on Tax Reform and Charities

Posted: February 15, 2013 Filed under: Nonprofits and Philanthropy, Shorts, Taxes and Budget Leave a comment »See a 2-part video of testimony and discussions before the Ways and Means Committee on “Tax Reform and Charities.” To get a sense of Ways and Means members’ views on the related policy issues, the first panel, with the following presentations, in order: myself; Kevin Murphy, Chair, Board of Directors of the Council on Foundations; David Wills, President of the National Christian Foundation; Brian Gallagher, President & CEO of United Way Worldwide; Roger Colinvaux, Professor of Catholic University DC Law School and adviser for the Tax Policy and Charities project at the Urban Institute; Eugene Tempel, Dean of the Indiana University School of Philanthropy; Jan Masaoka, CEO of California Association of Nonprofits. Copies of all testimonies can be found online.

See also our Tax Policy and Charities website for many related studies and data.

The first video begins after about 33 minutes of set up and administrative matters:

In addition, the Urban Institute will be hosting a conference on “The Charitable Deduction: A View from the Other Side of the Cliff” on Thursday, February 28, 2013. Registration is now open.

How Tax and Transfer Policies Affect Work Incentives

Posted: February 14, 2013 Filed under: Economic Growth and Productivity, Income and Wealth, Job Market and Labor Force, Shorts, Taxes and Budget 1 Comment »When the design of safety net programs is considered alongside that of our tax code, it is easy to see that our tax and transfer systems need to focus less on increasing consumption and more on promoting opportunity, work, saving, and education.

The government doesn’t affect work incentives just through direct taxes. Implicit taxes—that is, penalties for earning additional income—are everywhere, whether in TANF or SNAP, Medicaid or the new health exchange subsidy, PEP or Pease (reductions in tax allowances for personal exemptions and itemized deductions), Pell grants or student loans, child tax credits or earned income tax credits, unemployment compensation or workers compensation, or dozens of other programs. These implicit taxes combine with explicit taxes to create inefficient and often inequitable, certainly strange and anomalous, incentives for many households.

At some income levels, families face prohibitively high penalties for moving off assistance. Accepting a higher paying job could mean a steep cut in child care assistance for a single worker with children, for instance. For some, the rapid phaseout of benefits can offset or even more than offset additional take-home pay. Asset tests in means-tested programs create similar barriers to saving.

Not getting married is one way that people avoid some of these penalties or taxes and is the major tax shelter for low- and moderate-income households with children. Our tax and welfare system thus favors those who consider marriage an option—to be avoided when there are penalties and engaged when there are bonuses. The losers tend to be those who consider marriage a social or religious necessity.

The high rates and marriage penalties arising in these systems occur partly because of the piecemeal fashion in which they are considered. Efforts to design benefit packages more comprehensively could greatly improve both the incentives families face and the quality and choice of benefits they receive.

For more details, see my congressional testimony for today’s hearing on “Unintended Consequences: Is Government Effectively Addressing the Unemployment Crisis?” before the Committee on Oversight and Government Reform.

Tax Reform and Charitable Contributions

Posted: February 14, 2013 Filed under: Nonprofits and Philanthropy, Shorts, Taxes and Budget 1 Comment »The debate over the charitable deduction mistakenly pits those who acknowledge that the government needs to get its budget in order against those who recognize the extraordinary value of the charitable sector. The tax subsidy for charitable contributions should be treated like any other government program, examined regularly, and reformed to make it more effective. In fact, the charitable deduction can be designed to strengthen the charitable sector and increase charitable giving while costing the government the same or even less than it does now.

What’s the trick? Take the revenues spent with little or no effect on charitable giving, and reallocate some or all of them toward measures that would more effectively encourage giving.

For example, to increase giving Congress can do any or all of the following:

- allow deductions to be given until April 15 or the filing of a tax return;

- adopt the same deduction for non-itemizers and itemizers alike;

- consider proposals to ease limits on charitable contributions, such as allowing contributions to be made from individual retirement accounts (IRAs) and allowing lottery winnings to be given to charity without tax penalties;

- raise and simplify the various limits on charitable contributions that can be made as a percentage of income;

- reduce and dramatically simplify the excise tax on foundations; and

- change the foundation payout rule so it does not encourage pro-cyclical giving.

Congress can more than pay for these changes with little or no reduction in revenue if it would:

- place a floor under charitable contributions so only amounts above the floor are deductible (economists generally believe that some base amount of contributions would be given regardless of any incentive, thus floors have less effect on giving);

- provide an improved reporting system to taxpayers for charitable contributions;

- limit deductibility for in-kind gifts where compliance is a problem or the net amount to the charity is so low that the revenue cost to government is greater than the value of the gift made; and

- to help the public monitor the charitable sector, require electronic filing by most or all charities.

Budget and tax reform are now unavoidably intertwined. When it comes to the tax law concerning charitable contributions, we can do a lot to make our subsidy system more effective from both a fiscal and a charitable sector standpoint.

For more details, see my congressional testimony for today’s hearing on “Tax Reform and Charitable Contributions” before the Committee on Ways and Means.

Desperately Needed: A Strong Treasury Department

Posted: February 13, 2013 Filed under: Columns, Taxes and Budget 2 Comments »Alexander Hamilton, the first Secretary of the Treasury, set the bar very high. The Senate is about to begin debate over President Obama’s nomination of Jack Lew to be Treasury Secretary. Lately, confirmation hearings have often focused on either the personal foibles of candidates or relatively evanescent policy disputes that are soon forgotten. But at a time when fiscal policy is so critical to the nation’s well-being, the Senate should not forget the critical role Treasury has played in forging that agenda.

The key question for the Senate: will Treasury continue to play that powerful role under Lew’s stewardship?

While Hamilton could be mercurial and even buffoonish in his monarchial tendencies and late military ambitions, he was extraordinarily visionary in molding institutions and organizations to meet the fiscal needs of the new nation. Whether writing Federalist Papers or engaging in the nation’s first Grand Bargain on the budget—to pay off Revolutionary War debt in exchange for the establishment of the capital in the District of Columbia—his prescient gaze stretched far into the future, finding limitless possibility for this great nation.

Perhaps nowhere is his legacy more embodied than in the Treasury Department that he helped create and nurture to handle the nation’s debt obligations, taxes, and its budget. That legacy has been threatened by a modern department weakened by the usurpation of its functions.

Remember that the president is the only elected official our founders explicitly tasked to represent the nation as a whole. We expect partisanship among members of Congress because they represent different constituencies, though today the influence of special interests transcends congressional boundaries. The Chamber of Commerce, AARP, National Rifle Association, and AFL-CIO each understand the levers of power, even to the point of knowing how to scare an entire legislature to inaction with a few million dollars of campaign contributions or “scare” leaflets to their membership. I’m not saying that these groups don’t have views worthy of consideration, but they do not—I repeat, do not—represent the “general welfare” that our Constitution explicitly mentions in its preamble and its taxing and spending clause.

The executive branch is no longer organized along a few simple lines such as treasury, state, defense (or war), and justice—departments dedicated to what might be considered general welfare functions. The branch is now dominated by departments dedicated to special constituencies or tasks that generate special interest pleading such as agriculture, commerce, labor, housing, health and human services, and education. In turn, the White House is full of individuals whose jobs revolve around placating these constituencies, as well as pollsters and political advisors whose jobs center more on sound bites than sound policy.

Interestingly, one of the earliest fights between our political parties was over whether the federal government should get involved in arenas like agriculture or education. While Hamilton, was on the side of those favoring those efforts, both sides agreed that if such spending took place, it should still favor the general interest and not favor any specific section of the country over another. Today, particular constituencies are the dominant beneficiaries of many of our spending and tax subsidy programs. Does anyone really think that subsidies for sugar growers or early retirees or owners of oil companies and expensive vacation homes serve the general welfare?

When it comes to spending, taxing, and budgeting in the modern era—especially when the government has made too many promises to too many people—the Treasury Department remains the only agency that can restore order by offering broad reform packages centered on the general welfare.

Other arms of government simply lack the tools to deal with today’s unique fiscal challenges. If we set aside those mainly focused on special constituencies or tasks, the options are limited. The White House can and should help the president agree to propose what should be built, but it doesn’t have the personnel to figure out its plumbing and engineering. The only two budget competitors might be the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) and the Office of Management and Budget (OMB). CBO serves the Congress and not the President, and it abstains from proposing policy, partly to protect its now-ascendant role as neutral scorekeeper. Neither CBO nor OMB puts together cross-cutting packages the way that Treasury has done, when allowed. They do provide laundry lists of options, but that tends to foreclose, say, adopting an efficiency improvement in one area and offsetting its potentially regressive effects in another. OMB, in turn, has few economists on staff and has little tradition in issuing reports.

Treasury also sits in the unique position of having to worry about the ways and means of paying for things. It alone must deal with what I call the “take-away” side of the budget ledger. Constantly confronting how to administer taxes or float bonds, it’s in its very blood to balance potential benefits with costs and reduce politicians’ incentive to operate on the “give-away” side of the budget by enacting tax cuts and spending increases for which future generations will have to pay.

One other part to solving our fiscal puzzle involves understanding the role of committees or assemblies of politicians. The role of these groups is to approve, not design, policy, and delegating that latter function to them neglects the role of the executive in both business and government. There was a reason fiscal policy shifted to a strong Treasury and away from the committees operating under the weak Articles of Confederation.

In assuming the executive role of Treasury Secretary, will Jack Lew follow Hamilton’s example by leaving a stronger Treasury as a legacy? Will he help move us down a viable path for getting out of our current fiscal mess? I suggest he is unlikely to succeed at one without accomplishing the other.

Who Is Insured or Not Insured by Government?

Posted: February 6, 2013 Filed under: Columns, Health and Health Policy, Taxes and Budget 3 Comments »One of the many dilemmas surrounding federal health care policies is that the government only partially insures most people when it subsidizes health care, but we want to pretend that once “insured” we are all entitled to the maximum health care available. This puts a lot of weight on the definition of “insurance” and creates misunderstandings about what the government does and does not do.

This issue came up in a column by Bruce Bartlett, who notes that Republicans may now oppose an individual mandate, but they do support (directly or indirectly) a mandate on hospitals to provide emergency care. Moreover, while ignoring their effective support of this mandate, and the effective taxes necessary to pay for it, Republicans maintain that the emergency-care mandate means that everyone has some amount of insurance coverage, however partial it may be.

This debate raises the question of what it means to be “insured.” No government plan covers everything. For those soon to have access to the exchange subsidy available through Obamacare, the “silver” and “bronze” plans that could be subsidized still cover only some costs. Medicaid, in turn, generally pays providers less than do other insurance plans; as one result, the more highly paid (and, often, more highly skilled) providers are less available. Similarly, Medicare does not cover all health services, including long-term care, and some doctors now refuse new Medicare patients, though that system’s payment rate is still higher than Medicaid’s.

You may argue that you want equal coverage—if some people get Cadillac coverage, everyone should. However, no elected official from either party seems willing to raise the taxes necessary to pay for such an expensive system. The reason is obvious: such health care would absorb all the revenue currently raised by the federal government and then some, leaving nothing for other government functions.

Even then, some people would step outside the system and buy a Mercedes policy, so inequality in health care would remain. Thus, the notion that everyone gets the same health insurance coverage, even in the most nationalized health system, is pure myth. But if people are not going to receive the Cadillac or Mercedes coverage from government that others obtain privately, how should Congress design policy with those multiple gaps in mind?

I don’t think there is any easy answer, but I do think that researchers and analysts should be more precise when reporting on “insurance” coverage. For example, the Congressional Budget Office produces counts of how many people would be insured under various options, but such estimates by themselves are misleading. Insured and not insured for what? For instance, if everyone received a simple (say, $5,000) voucher, with few restrictions other than that it must cover health care, almost everyone would buy at least a $5,000 insurance policy. On the other hand, if government dictated that the voucher had to be used to buy an expensive plan that many people couldn’t afford, then supplying a voucher would not produce fairly universal (yet partial) coverage.

Alternatively, one can’t assume that a highly regulated system will automatically provide whatever care is specified, since what it pays affects which providers participate in the system. The implicit assumption—and I am not judging it here—may be that many providers are so overpaid that cutbacks would have only limited effect on the care provided or the quality of the doctors and nurses who would accept a lower-paying career.

The ideal but difficult approach for researchers and budget offices, I think, is to note as best as possible what coverage is provided by regulation or subsidization of emergency rooms, Medicaid, Medicare, exchanges—indeed, of each government engagement in the health care economy. Note the expected gaps, whether in preventive care, higher-priced doctors, drugs, or other services. Finally, compare the extent to taxpayers and insured individuals avoid coverage gaps by paying higher taxes or more for their insurance.

In any case, a dichotomous count of who is “insured” or “not insured” is too simplistic. Almost any government health insurance policy is partial in care and cost. If Republicans want to claim that emergency room care is a type of insurance, then they should also acknowledge what is not insured through that mechanism and the implicit taxes on those who end up covering the emergency room cost. If Democrats want to claim that vouchers provide less insurance than a more regulated system, then they, too, should specify just what additional insurance they claim will be covered, at what cost to whom. Both parties should also make coverage comparisons for systems that are equally cost constrained.