Beyond Wayfair, Can Nations and States Cooperate in Collecting Taxes?

Posted: July 9, 2018 Filed under: Uncategorized Comments Off on Beyond Wayfair, Can Nations and States Cooperate in Collecting Taxes?This column first appeared on TaxVox.

The brilliant Tax Notes columnist Marty Sullivan once summarized one of the great dilemmas in taxation: “It’s simply impossible to put a precise geographical subscript around ‘where’ taxes should be collected.” He mainly had in mind locating the source of capital income, but geography again reared its head recently when the Supreme Court’s South Dakota v. Wayfair, Inc. decision tackled the question of when states can require online retailers to collect sales taxes.

In both cases, it is difficult, if not impossible, for taxing jurisdictions to resolve these issues on their own. But they create important opportunities for these authorities to work together to develop solutions that are fair to taxpayers while assuring that government collects tax that is legitimately owed.

The issues are not easy to resolve. Countries struggle to sort out where a firm’s income is earned when its headquarters, production, marketing, research, and patents can be located anywhere in the world, when its sales routinely cross borders, and when some goods and services can be transferred or sold multiple times as intermediate products along the way toward a final sale.

This environment even affects charities, many of which routinely violate state and national laws simply by maintaining websites that can receive donations from anywhere but have not registered in every jurisdiction that might require it.

The Supreme Court’s Wayfair decision added to these boundary disputes. The Court ruled that states can obligate an on-line retailer to collect and remit sales taxes even if that firm’s website and physical facilities (such as manufacturing and headquarters sites) reside outside their jurisdiction.

Senator Heidi Heitkamp (D-ND) at a recent Tax Policy Center (TPC) event, as well as my colleague, Howard Gleckman, have noted how, for decades, Congress has failed to enact federal legislation to smooth out the administrative nightmares that online and catalog sales can create. But neither have the 50 states been able to agree on a coherent collections model.

However, there are examples of progress both internationally and among the US states.

My TPC colleagues Richard Auxier and Kim Rueben have detailed the various state efforts to use a streamlined sales tax agreement to address common measurement and registration issues caused by the evolution of on-line sales taxes.

Internationally, the OECD and G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) project laid out fifteen actions that nations can employ to increase transparency and adopt common standards for treating issues such as interest income, transfer pricing, and controlled foreign corporations.

So far, most of these multilateral efforts have been voluntary. Governments could be more aggressive in developing common practices if legislation or treaties made them mandatory. That big step is often opposed by those who benefit from the status quo, either through existing legislative favoritism or their ability to evade/avoid the laws. Yet pressure to resolve these issues continues to grow.

For example, the federal government could pre-empt some state actions by adopting a nationwide retail tax that it shares with the states according to a fixed formula. For many years, the federal government granted a credit against federal estate tax of up to 100 percent for payments of a state estate tax that included certain features. That gave states a significant incentive to adopt a common estate tax base since failing to do so effectively meant turning revenue over to the federal government.

Similarly, the European Union aims for a standardized tax base for the value-added tax, though its member countries may still set their own rates and are allowed some flexibility in defining their tax base.

In the face of growing complexity, even businesses are embracing common standards, at least up to a point. For instance, brick-and mortar retail firms have complained about their competitive disadvantage when on-line sellers do not collect tax for selling the same goods and services. In a sense, these firms are arguing for a common tax base to apply to both physical and on-line or mail-order sales.

Many firms’ finance and accounting officers complain about having to comply with a wide range of rules for defining income or sales tax bases among multiple jurisdictions. A multinational firm, for instance, may have to file income, sales, and value-added tax reports in thousands of jurisdictions. Even without foreign sales, a US firm may file hundreds of tax returns in the 50 states and numerous cities and counties. To address these concerns, third-party providers and software firms have jumped into this market by selling products to ease the burden on taxpayers and governments alike.

The evolution of the modern economy is only increasing pressure on taxing jurisdictions to cooperate and for federal systems to adopt laws or treaties that encourage or even require such cooperation among sub-national governments. Such efforts extend to registration, filing requirements, reporting, transparency, and definition of tax bases, and, sometimes, minimum tax rates.

These efforts always will be incomplete and ongoing, given legitimate pressures for tax competition and jurisdictional independence. But South Dakota v Wayfair, Inc. is an important step along this meandering path toward sometimes-workable conformity.

Why Government Budget Estimates Are Often Wrong

Posted: June 6, 2018 Filed under: Uncategorized Comments Off on Why Government Budget Estimates Are Often WrongThis column first appeared on TaxVox.

Government budget and tax analysts who estimate future federal revenues and spending are among the most talented people I know. They probably are a lot more accurate at what they do than typical academics or business consultants. However, their estimates frequently understate the true long-term costs of tax cuts or spending.

When estimators miss on the low side, it is often because they are trying to project costs of those government programs and tax subsidies that are both permanent or “mandated,” absent new legislation, and essentially open-ended.

Unlike programs where the government appropriates a fixed amount of money each year, the costs of mandated programs don’t need to be appropriated to be spent. Meanwhile, open-ended programs leave important determinants of cost, such as demand or price or definitions about who or what qualifies for the program, to decisions made by beneficiaries or service providers. When the two elements are combined, Congress effectively cedes long-term control of the costs to private individuals acting in their own, not necessarily the public’s, interest.

Estimation is simpler for mandatory programs or permanent tax benefits that are not open-ended. For example, estimators know that the cost of the child tax credit will equal the amount of the credit times the number of eligible children. Similarly, Social Security retirement benefits might grow rapidly but can be estimated with fair accuracy because they are set by formulas based on lifetime earnings that provide only limited discretion to recipients.

That is not so for Medicare, where beneficiaries and providers have often been allowed to appropriate resources to themselves. Consumers demand more access to healthcare treatment even as providers—who mostly are compensated based on volume—happily increase the supply of those treatments. Because there is little effective market discipline, health care provided by government creates a perfect fiscal storm. For example, suppose a drug company markets a new drug under government patent protection; it then sets a price; consumers demand the drug to address the ailment it treats; and—often—Medicare pays.

A similar phenomenon occurs with the open-ended tax subsidy for capital income, which is taxed at lower rates than ordinary income. Since ordinary income is taxed at a top rate of 37 percent while long-term capital gains are taxed at a top rate of 23.8 percent, taxpayers have an enormous incentive to recharacterize their income to benefit from the lower rate. The classic recent example: Hedge funds that have converted a share of their managers’ labor compensation income into lower-taxed long term capital gains income (carried interest).

Over the years, Congress and the IRS have played a game of whack-a-shelter with respect to preferential tax rates for capital income. Smart lawyers find a new way to turn ordinary income into lower-taxed capital gains, government (through either legislation or regulation) shuts it down, and then taxpayers and their advisors find another approach. That process makes it impossible to estimate government revenues for the long-run since estimators are supposed to assume the permanence of what is an inherently unstable law.

Forecasting capital gains revenue is even more difficult because investors can choose when to realize gains and, thus, pay the tax. As a result, gains can be earned over decades but are not taxed (and this generate no revenue) unless “realized” through an asset sale.

In a classic article, Nobel prize winning economist Joseph Stiglitz explained how individuals could take advantage of these arbitrage opportunities to reduce the taxes they pay. Given their voluntary nature, a large share of gains is never taxed because they are held until death—when their assumed cost in the hands of the heir is “stepped-up” to the market price at the time the person making the bequest passes away.

The newest example of an open-ended tax shelter is the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act’s 20 percent individual income tax deduction for income from pass-through businesses such as partnerships and sole proprietorships. It blows a hole in the government fisc so large than a Mack truck could be driven through it—as long as the operator is a sole proprietor. Congress attempted to limit the benefit to some types of earners and some types of businesses, but tax lawyers are busily finding ways to convert excluded businesses into qualified ones, and wage earners into independent business owners.

The structure of these types of laws makes estimating difficult enough. But two other factors make forecasting even more challenging.

The first is that the compounding of cost growth may take place years in the future and congressional scorekeeping conventions generally limit projections to the first 10 years, the so-called “budget window.” Underestimating a growth rate by a couple percent per year, for instance, compounds to a very large number over time.

The second is that estimators may be reluctant to project very large costs in the absence of empirical evidence. For example, the 20 percent tax deduction for pass-through income is new, and there is little information upon which to predict the magnitude of gaming that will occur. The revenue estimator doubtlessly will assume some gaming, but may not be imaginative and daring enough to forecast without much data a large multiplier for what lawyers or providers, in absence of further whack-a-shelter legislation, will invent for their clients.

Much is wrong with a system that allows enactment of open-ended mandatory spending programs and tax preferences. Until we repair that system, it is worth remembering there is a built-in bias towards underestimating their long-term costs.

Measuring the “Charitability” of Hospitals: Putting Meat on the Bones of the Grassley-Hatch Request

Posted: May 25, 2018 Filed under: Uncategorized Comments Off on Measuring the “Charitability” of Hospitals: Putting Meat on the Bones of the Grassley-Hatch RequestOn February 15, 2018, Senators Chuck Grassley (R-Iowa) and Orrin Hatch (R-Utah) requested specific information from the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) on its oversight activities of nonprofit hospitals. Skeptical about whether some or many nonprofit hospitals actually operate as charities, they sought evidence that they provide “community benefits.”

To provide evidence well beyond what the IRS considers, I suggest that they and the hospitals themselves adopt a tool I developed to help assess whether a charity fully utilizes the charitable resources available to it. It turns out that a hospital can qualify for tax exemption and provide community benefits while operating more as a partnership serving its doctors, staff, and managers than as a charity. The main value of this tool, however, is not for a top-down assessment by an understaffed IRS wading through a measurement swamp, but for self-assessment of charitable operations by truly mission-driven hospitals.

This measurement tool is simply a variation on the accountant’s most powerful tools: the income statement and the balance sheet. Using this tool goes beyond the traditional balancing of cash flows in and cash flows out, or of assets with liabilities, to what I call the uses and sources of those “resources” gathered to pursue the charitable activities of the hospital. Of course, it can be used by almost all charities, not just hospitals.

READ MORE AT TAXPOLICYCENTER.ORG

Challenges & Opportunities for Charities after the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act

Posted: May 21, 2018 Filed under: Nonprofits and Philanthropy, Taxes and Budget Comments Off on Challenges & Opportunities for Charities after the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs ActEugene Steuerle, Richard Fisher Chair at the Urban Institute and co-founder of the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center gave this presentation at the ABA Tax Meetings Exempt Organizations Committee luncheon in May 2018. A full transcript is available at taxpolicycenter.org.

“A pessimist sees the difficulty in every opportunity; an optimist sees the opportunity in every difficulty.”

I’d like to refine this idea, probably incorrectly attributed to Winston Churchill, with the wisdom of my teachers, by distinguishing among luck, serendipity, and misfortune. To me, luck—good or bad— results from random factors beyond our control. Serendipity reflects the good things more likely to happen when we put ourselves along a path with a higher-than-average probability of success, while misfortune happens, often unnecessarily, when we bet against a house that has stacked the odds in its favor.

I realize that the lexicographers may not fully agree with my definitions.

Chauncey M. Depew told the story that Noah’s wife one day was caught kissing the cook.

“‘Noah,’ she exclaimed, ‘I’m surprised!’

“‘Madam,’ he replied, ‘you have not studied carefully our glorious language. It is I who am surprised. You are astounded.’”

Are charities on a serendipitous path, where a virtuous cycle of improvement is more likely, or a path with greater odds of a vicious cycle of misfortune? I suggest that the treatment of charities in last year’s tax reform may reflect a path if not misfortunate at least less serendipitous than possible.

In any case, I want to spend most of this talk discussing why the current tax law is unsustainable and sets in motion forces for further reform. I then set out a bold but difficult agenda worth pursuing as we venture down that still-to-be-determined path.

READ MORE AT TAXPOLICYCENTER.ORG

How Recent Tax Reform Sounds a Clarion Call for Real Reform of Homeownership Policy

Posted: May 10, 2018 Filed under: Uncategorized Comments Off on How Recent Tax Reform Sounds a Clarion Call for Real Reform of Homeownership PolicyThis column first appeared on TaxVox.

By roughly doubling the standard deduction and limiting the deduction from federal taxable income of state and local taxes (SALT), the Tax Cut and Jobs Act of 2017 (TCJA) significantly reduced the tax benefits of homeownership, especially for middle-income households. Not only does it cap the deductibility of state and local taxes, including local property taxes, it also substantially reduces the number of taxpayers who will itemize deductions at all, including those who pay mortgage interest.

As a result, it raises important questions about the future viability of tax subsidies that primarily benefit higher-income taxpayers who own expensive, highly-leveraged homes. These changes made homeownership tax subsidies even more upside-down than pre-TCJA tax law and provide a tax incentive to further concentrate the distribution of private wealth.

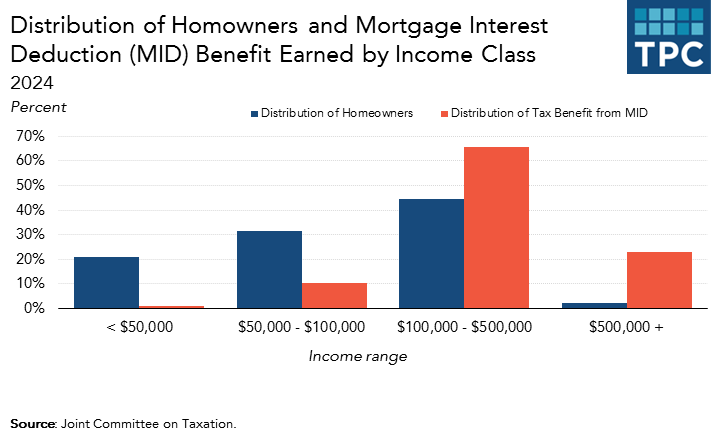

The Congressional Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) recently released projections on the future distribution of some of the tax benefits of homeownership. Out of 77 million projected homeowners in 2024, only about one-fifth will make $50,000 or less. Yet, they’ll comprise about half of all households, homeowners and nonhomeowners alike. These taxpayers with annual incomes under $50,000 will get only about 1 percent (or less than $400 million out of $40 billion) of the overall tax subsidy for home mortgage interest deductions. Meanwhile, households with more than $100,000 of income will garner almost 90 percent of the subsidy.

These estimates for the mortgage interest deductions understate the total value of tax benefits from homeownership. Property tax deductions are also skewed to the rich and the upper-middle class. At the same time, it is more beneficial to build up home equity largely tax-free than to pay income tax on the returns from money kept in a savings account. This additional incentive also benefits the haves more than the have-nots because it is proportional to the amount of equity a homeowner possesses. So those with a large amount of home equity are far better off than new, usually younger, homeowners who rely heavily on borrowing to purchase a home.

There is something of a paradox to the new tax law, however. The increase in the standard deduction, and the caps on deductions for home mortgage interest and state and local tax payments are all steps that make the overall tax system more progressive. And the reduction in tax incentives probably put a small brake on inflation in the value of housing, making it a bit more affordable for both renters and homeowners.

Still, as a matter of homeownership policy, the result is that only a little over one tenth of taxpayers—those who will still itemize after the TCJA—will have the opportunity to benefit from most tax subsidies for homeownership. And that will require advocates for extending ownership incentives to more low- and middle-income groups to make the case not simply for better distributing existing tax subsidies but for maintaining any at all. As the increase in the standard deduction shows, there are a lot of ways of promoting progressivity that do not entail subsidizing homeownership.

The case for homeownership subsidies in the tax code and elsewhere rests mainly on the following two grounds: (1) homeownership is a way of promoting better citizenship and more stable communities; and (2) homeownership helps improve wealth accumulation by nudging many who might not otherwise save to do so by paying off mortgages and making capital improvements on their houses.

The saving argument is one that does apply mainly to low- and moderate income households. Homeownership is the primary source of saving for these households, even more important than private retirement saving. If one cares about the uneven distribution of wealth, and related issues of financing retirement for moderate-income households, then encouraging wealth accumulation through housing may be an appealing strategy.

The bottom line: When it comes to homeownership, the TCJA has left the nation with an upside-down tax incentive that applies to only about one-tenth of all households—nearly all of them with high incomes.

Such a design doesn’t pass the laugh test for political sustainability. The new tax law’s crazy remnant of a homeownership tax subsidy should encourage policymakers to rethink housing policy, including tax benefits and direct spending programs for both renters and owners. Given the structure of the TCJA’s tax subsidies, the bar is relatively low for policymakers to find an improvement.

How Late-in-Life Dads Like Donald Trump Are Eligible for a Social Security Bonus

Posted: April 9, 2018 Filed under: Aging, Taxes and Budget Comments Off on How Late-in-Life Dads Like Donald Trump Are Eligible for a Social Security Bonus

This article, coauthored with Allan Sloan, first appeared in ProPublica and The Washington Post.

Would you believe that President Donald Trump is eligible for an extra Social Security benefit of around $15,000 a year because of his 11-year-old son, Barron Trump? Well, you should believe it, because it’s true.

How can this be? Because under Social Security’s rules, anyone like Trump who is old enough to get retirement benefits and still has a child under 18 can get this supplement — without having paid an extra dime in Social Security taxes for it.

The White House declined to tell us whether Trump is taking Social Security benefits, which by our estimate would range from about $47,100 a year (including the Barron bucks) if he began taking them at age 66, to $58,300 if he began at 70, the age at which benefits reach their maximum.

Of course, if Trump, 71, had released his income tax returns the way his predecessors since Richard Nixon did, we would know if he’s taking Social Security and how much he’s getting. There’s no reason, however, to think that he isn’t taking the benefits to which he’s entitled.

Meanwhile, Trump’s new budget proposes to reduce items like food stamps and housing vouchers for low-income people. It doesn’t ask either the rich or the middle class to make sacrifices on the tax or spending side. And it doesn’t touch the extra Social Security benefit for which Trump and about 680,000 other people are eligible.

The average Social Security retiree receives about $16,900 in annual benefits. Does it strike you as bizarre that someone in Trump’s position gets a bonus benefit nearly equal to that?

Does it seem unfair that by contrast to Trump, most male workers — and for biological reasons, an even greater portion of female workers — can’t get child benefits because their kids are at least 18 and out of high school when the workers begin drawing Social Security retirement benefits in their 60s and 70s?

Trump is eligible for the Late-in-Life-Baby Bonus, as we’ve named it, because the people who designed Social Security decided in 1939, about five years into the program, that dependents and spouses needed extra support. They didn’t think much (if at all) about future expansion in the number of retirees, primarily male, who would have young kids.

The Late-in-Life-Baby Bonus goes to about 1.1 percent of Social Security retirees and costs about $5.5 billion a year. That’s a mere speck in Social Security’s $960 billion annual outlay.

Yet the Late-in-Life-Baby Bonus is a dramatic — and symbolic — example of hidden problems that plague Social Security, problems that few non-wonks recognize and that reform proposals have largely ignored.

Those problems are why the two of us — Allan Sloan, a journalist who has written about Social Security for years; and C. Eugene Steuerle, an economist who has written extensively about Social Security, co-founded the non-partisan Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center and is the author of “Dead Men Ruling: How to Restore Fiscal Freedom and Rescue Our Future” — combined forces to write this article.

We want to show you how we can help Social Security start heading in the right direction before its trust fund is tapped out, at which point a crisis atmosphere will prevail and rational conversation will disappear.

Calling for Social Security fixes isn’t new, of course, but the calls usually focus primarily on fixing the increasing gap between the taxes Social Security collects and the benefits it pays.

For us, however, the Late-in-Life-Baby Bonus is an example of why reform should not only restore fiscal balance but should also make the system more equitable and efficient, more geared to modern needs and conditions, and more attuned to how providing ever-more years of benefits to future retirees puts at risk government programs that help them and their children during their working years.

If all that mattered were numbers, we could easily provide better protections against poverty with no loss in benefits for today’s retirees, while providing higher average benefits for future retirees. But that works only if the political will is there to update Social Security’s operations and benefit structure. After all, a system designed in the 1930s isn’t necessarily what we’ll need in the 2030s.

And make no mistake about how important Social Security is. Millions of retirees depend heavily on it. According to a recent Census working paper, about half of Social Security retirees receive at least half their income from Social Security — and about 18 percent get at least 90 percent of their income from it. Add in Medicare benefits, and retirees’ reliance on programs funded by the Social Security tax are even higher.

Given the virtual elimination of pension benefits for new private-sector employees and the increasing erosion in pensions for new public-sector employees, Social Security will likely be needed even more in the future than it is today.

Simply throwing more money at Social Security isn’t the way to solve its imbalances, much less deal with the Late-in-Life-Baby Bonus and some of the other bizarre things we’ll show you.

Money-tossing would just continue the pattern of recent decades that provides an ever increasing proportion of national income and government revenue to us when we’re old (largely through Social Security and Medicare), and an ever smaller proportion when we’re younger (anything from educational assistance to transportation spending). This shortchanges the workers of today and tomorrow who will be called upon to fork over taxes to cover the costs of Social Security and other government programs for their elders.

We began with the Late-in-Life-Baby Bonus because giving people like Trump — a wealthy man with a young child from a third marriage — an extra benefit unavailable to 99 percent of retirees is a dramatic example of how problems embedded in Social Security cause inequities and problems that few people other than Social Security experts know about.

Think that we’re overreacting to a minor quirk? We aren’t. Here are some additional aspects of Social Security that we think violate standards of equal justice and common sense:

There’s the Single Parent Shortchange, whereby many single parents — largely mothers with below-average earnings — pay Social Security taxes to cover spousal and survivor benefits for other people even though the solo parents can’t receive them. Sure, many people contribute toward benefits they will never see, especially if they die before retirement age. But the Single Shortchange strikes us as horribly unfair. Single parents are among the lowest income payers of Social Security taxes. Why should they subsidize other folks’ never-working spouses in a way that gives the biggest benefits to the best-off people?

Then there’s the Agatha Christie Benefit: Some divorced people get a bonus from Social Security only if their former spouse dies. And the Serial Spouse Bonus: If someone has had, say, three spouses, each might get the same full spousal and survivor benefits available to the one lifetime spouse of another worker — provided that each marriage lasted at least 10 years. If a marriage lasts nine years and 364 days, the spouse gets zippo.

The Equal Earner Penalty means that a couple with two people each earning $40,000 gets about $100,000 less in lifetime benefits than a couple with one spouse earning $80,000 and the other earning nothing. This happens even though both couples and their employers pay identical Social Security taxes.

Many if not most of these inequities would be illegal in private retirement plans.

Fixing the Late-in-Life-Baby Bonus and the other inequities we mentioned (as well as plenty that we omitted) is more about remedying injustice than cutting costs; giving some people more benefits and others less would pretty much offset each other.

The system needs to be overhauled not simply to become more fair by giving less to the Trumps of the world and more to the less fortunate among us, but because Social Security, created in the 1930s, was largely constructed around a world in which married women were expected to stay at home. People also had shorter lifespans then and retired later, so that today retirees receive benefits for 12 more years on average than retirees in the system’s earlier days.

Back in 1965, there were about four workers for every person drawing benefits. Currently the ratio is in the low threes. Now, the decline in birth rates is hitting with a bang as baby boomers retire en masse, with the ratio expected to fall to about 2.2 in 2035. Each baby boomer retirement leads to an increase in takers and a decrease in makers.

Not dealing with this decline in workers-to-beneficiaries — a good chunk of which is caused by Social Security treating people as young as 62 as “old” — has broad implications for the revenues available for all government services, not just Social Security, as well as for the growth rate of our economy.

Even as fewer workers support more retirees, the average value of Social Security retirement benefits continues to rise. Look at the increasing “present value” of Social Security benefits for a two-income 65-year-old couple earning the average wage each year and expecting to live for an average lifespan.

In 1960, such a couple needed to have on hand $269,000 (in 2015 dollars) in an interest-bearing account to cover the cost of their lifetime benefits. Today, it’s about $625,000. In 2030, it will be about $731,000. And in 2055, when a Millennial age 30 this year turns 67, the full retirement age under current law, the present value of scheduled benefits hits seven digits: $1,029,000. Include Medicare, and benefits are about $1 million for today’s couple, rising to $2 million for the millennial couple.

These benefit-value increases are caused by a combination of longer lives for retirees and Social Security formulas that increase benefits as wages rise.

These numbers matter because Social Security isn’t like an Individual Retirement Account or a pension plan that sets money aside for you today for use when you retire. It’s mainly an intergenerational transfer system: Today’s workers pay Social Security taxes to cover their parents, who previously paid to cover their parents, who paid to cover their parents. That’s the way the system has worked since its founding in 1935. Social Security taxes paid by current workers and their employers get sent to beneficiaries, not stashed somewhere awaiting current workers reaching retirement age.

The system does have a trust fund that in the early 1980s was about to run out of money. A crisis loomed. As a result, after a report by the Greenspan Commission, Congress in 1983 enacted reforms that included gradually raising the normal retirement age (but not the early retirement age) and subjecting some Social Security retirement benefits to federal income tax.

This led to temporary surpluses while baby boomers were in their peak earning years. But now that boomers are retiring rapidly, Social Security’s tax revenues are falling farther and farther behind benefits being paid out.

The trust fund is projected to run dry in about 15 years. Meanwhile, every year without reform adds to the share of the burden required of the young, who already are scheduled to have lower returns on their Social Security contributions than older workers.

Do you think that if someone offered millennials a choice, they would want to face huge student debt, declining government investment in their children and higher future taxes (which are inevitable as deficits mount) — in exchange for a more generous retirement than today’s retirees get? Or would they prefer a system that treats them and their children better when they’re younger?

We’re both way past millennial age — but we know which we would prefer.

Now, we’ll show you how we can tweak Social Security to address the problems we’ve discussed without cutting benefits for current retirees or denying future retirees average benefits higher than current retirees get.

It’s about math. Social Security pays out far more than would be required to provide well-above-poverty-level benefits to all elderly recipients. Future growth in the economy will help tax revenues and benefits rise, which would give us room to modify the payout formulas and deal with problems that this iconic program isn’t addressing.

Those problems include poverty and near-poverty for millions of retirees, particularly the very old. That problem is greater for people who retired at 62 rather than waiting for their full retirement age, a move that locks them into lower payments for the rest of their lifetimes.

How can we orient the system more progressively to the needs of modern society, provide a stronger base of protection for all workers, and slow the growth rate of benefits to bring the system into better balance? To shore up Social Security permanently, it’ll be necessary to slow down the overall growth in benefits, encourage more years of work and end the pattern of people having ever-longer retirements as lifespans increase and Social Security doesn’t adapt its rules. At some point, it will also require a revenue (i.e., tax) increase, too.

Here, in simplified form, are some suggestions for making Social Security more modern and more fair.

- Change the benefit structure. Reduce the level of benefits that retirees get in their 60s and early 70s but give them higher-than-now benefits in their mid-to-late 70s and beyond. That would shift resources to retirees’ elder years when they have greater needs, including a higher probability of having to pay for long-term care.

- Raise the minimum benefit. Have a strong minimum benefit for most elderly that’s indexed to wage growth, which typically exceeds inflation. This would raise benefits for one-third to one-half of the elderly in a way that will essentially remove them from poverty.

- Trim benefit growth for those at the top. Offset at least part of the cost of higher minimum benefits by paying the highest-paid recipients less in the future than they would get under the current formula. Slow the rise in benefits for future retirees with way-above-average lifetime earnings by indexing their benefits to inflation rather than to wage growth.

- Index the retirement age. Having people work for additional years helps pay for higher levels of both lifetime and annual benefits. So if people on average are living a year longer, they should have to work a year longer. Those additional income and Social Security taxes would help support both Social Security and national needs that are higher priority than paying additional retirement years. Gradually phase out the early-retirement age that leads many healthy couples to retire on Social Security for close to three decades for the spouse who lives longer.

- Make spousal and survivor benefits more fair. Modify these benefits so that they provide higher benefits for those with greater needs rather than giving the richest bonuses to the richest spouses even when they contributed less in taxes than lower-income spouses. Otherwise, use rules similar to what private pensions use, so that benefits are shared fairly for the time of marriage together.

And one final thing: Bye-bye Late-in-Life-Baby Bonus. Stop paying retirees extra for children under 18. Continue the young-child bonus for widows or widowers below retirement age, and for people on disability.

Eliminating that bonanza for older parents would be a symbolic first step. And who can say? Perhaps now that lots more people (including possibly Trump himself) know that the Late-in-Life-Baby Bonus exists, our leaders might just be embarrassed enough to realize that the sooner Social Security is adapted to modern needs and circumstances, the better.

If this results in starting to fix Social Security the right way, the Late-in-Life-Baby Bonus will have delivered a big-time bonus of its own. The beneficiaries would be our future retirees, our workers and our country as a whole.

Donald Lubick: Public Servant

Posted: April 7, 2018 Filed under: Uncategorized Comments Off on Donald Lubick: Public ServantThis column first appeared on TaxVox.

The Tax Policy Center is hosting its third annual Symposium in honor of Donald C. Lubick on Monday, April 9 at the Brookings Insitution. Given the chaos that defines tax policy these days, it seems like a good time to explain why we both honor Don and desperately need more leaders like him.

Don served presidents Kennedy, Johnson, Carter, and Clinton, and served on President-elect Obama’s transition team in 2008. That’s public service over more than four decades. He also worked to improve tax policy from Buffalo, NY to Eastern Europe.

A protégé of the legendary Stanley Surrey, Don is guided by basic principles of tax policy: efficiency, simplicity, and the concept of horizontal equity–idea that that equals should be treated equally under the law.

Even though he started out as a Republican, he also believed in progressivity. Yes, Don was once a Republican. His great friend Stu Eizenstat told me that the Kennedy Administration almost didn’t hire Don. The White House asked Stan Surrey why it should give an important tax policy job to a registered Republican. The answer, of course, was that Don was talented about tax policy and that he would serve Democratic Administrations as well as any other.

The principles that are so important to Don do not always lead to exact conclusions about what policy is best, but they create important boundaries that frame policymaking.

As one of Don’s students at Treasury, I learned that while politics requires compromises, the first draft of policy should hew to those principled boundaries.

Don surely didn’t win every battle. He failed to convince President Carter to veto the 1978 tax cut that included almost no reform. And Stu recounts that the only time Don ever read congressional testimony verbatim was when he was asked to defend some energy tax credits.

When I first worked with Don, Treasury’s Office of Tax Policy played a much larger role formulating policy for both the President and Congress than it does today. Few outside the office can fully know how they benefit from Don’s work building upon the culture, ethic, and practice of that vital office.

Unfortunately, as the legislative branch reasserted control over each stage of tax policy formulation, and the White House asserted ever more control over the Treasury, decisions became more politicized much earlier in the process, losing focus on those policy foundations that are so important to Don. As we saw last year, Congress has yet to figure out how write that all-important first draft in a way that will sustain a principled basis as that tax legislation moves toward enactment.

Reflecting on that trend, Don famously quips that each of his tours at Treasury was better than the next. He repeatedly answered the call to public service, at significant financial cost. And while in private practice, he forswore the allure of the giant law firm, choosing instead firms where teamwork was more valued. He leads through vision, creates an esprit de corps among those staff with whom he works, makes debates over tax policy exciting, and easily shares credit.

All of us at TPC are pleased to honor a person of such character, whose legacy will long influence how good tax policy is made and help us recognize when it is not.

Pete Peterson and Our Chaotic National Debates

Posted: April 4, 2018 Filed under: Uncategorized Comments Off on Pete Peterson and Our Chaotic National DebatesThis column originally appeared on TaxVox.

Each person’s death gives us a moment to pause and ask what lessons their lives offer for us. Here is a lesson from the life of Peter G. (Pete) Peterson, who died on March 20, 2018 at the age of 91: We could reduce our current political chaos by shifting more political resources toward efforts to find sensible, consensus solutions to policy challenges.

Pete Peterson played large on the national stage, in business, politics, and policy. In recent years, he focused much of his energy—and his money—on the Peter G. Peterson Foundation.

Pete’s particular concern was government budgets, which is the focus of his foundation. His long-standing push for fiscal prudence has been attacked by some on both left and right, but his concerns rested on two apolitical truths: Debt cannot keep rising faster than income, and the consequences of fiscal policy go beyond budget deficits to affect issues such as how we invest in our children. He sometimes called himself the last of the Rockefeller Republicans, taking on Democrats and Republicans alike.

I worked with Pete as Vice-President of his foundation. The Urban Institute and the Tax Policy Center, where I currently work, receive research grants from his foundation. So, I am not a disinterested party when it comes to either Pete or budget policy. But Pete’s life was an example of how to engage in national debates.

Today, these debates are often dominated by partisanship and what we might call “self-interest” groups. This aspect of politics—and political money– won’t go away, but it’s way out of proportion to how we should be spending our precious resources in engaging policy issues.

Unfortunately, instead of seeking devoting a fair share of resources toward creating a rational common ground, we get sucked into supporting an escalating arms race aimed at opposing those idiots on the other side.

The large national organizations that pursue their own particular agendas–whether the NRA, AARP, Chamber of Commerce, or AFL-CIO–may represent legitimate issues. But by scaring us into believing they are preserving our very lives and liberty, and that we should be offended at any reform that asks us to give up anything, they distort reality, raise more money, and attain even more influence and power.

It is the same with electoral politics. Noncompetitive legislative districts have long elected representatives who serve the median voter in their own party, but not the district as a whole. Interest groups have long figured out how to exploit that system to further divide and conquer.

The media feeds on and amplifies the frenzy. It seeks controversy, which is not the same as seeking truth. Like moths led to a flame, our media has become easily manipulated by those who recognize that controversy creates attention; attention produces fame; and fame enhances power.

So, what does Pete have to do with all of this? None of what I have noted about the use of power is new, but the way to prevent self-interest groups from dividing us for their own objectives is simple: unite. Stop being so outspent by those groups. Instead of lavishing donations on the arms race of such interest groups and the two major political parties, do what Pete did and focus resources on efforts to create that elusive common ground for rationale dialogue.

Pete had nothing against groups with very specific policy agendas. After all, he funded several. But those groups do not focus on convincing policymakers to shift resources from other special interests for their own benefit. Rather, they argue for budget and trade policy that they believe enhance the greater good. You don’t have to agree with Pete’s priorities to recognize that he was not attempting to promote any political party’s agenda, but to support those who could compromise civilly on common objectives. It is a lesson worth remembering.