Did the Financially Insecure Secure Donald Trump’s Victory?

Posted: December 21, 2016 Filed under: Income and Wealth, Job Market and Labor Force 1 Comment »

In a classic case of Monday-morning (or Wednesday-morning) quarterbacking, many of us tend to seek one simple explanation for why Donald Trump won the recent presidential election. New analysis from some of my colleagues at the Urban Institute shows that the real reasons are more complex and transcend sound bites.

As part of our Opportunity and Ownership Initiative, Diana Elliott and Emma Kalish have assessed ongoing election narratives with some on-the-ground facts and an interactive map. They compare county-by-county elections results with various financial and demographic characteristics of voters. Interestingly, Diana and Emma conclude that financial insecurity did not drive voting preferences.

In fact, Hillary Clinton won just 4 of the 55 counties (or county equivalents) whose residents had the highest average credit scores (720 and above). High credit scores imply bills paid promptly and the type of financial stability that comes with paying off a mortgage over time. Clinton did win the 11 counties with the lowest scores.

Race and education were strong factors: generally speaking, white consumers were more likely to vote for Trump, those with bachelors’ degrees or higher to vote for Clinton.

These results provide information not only about voting patterns but about whether different policy initiatives would help those who feel ignored or left out by government, another part of the post-election debate. Further research might also reveal whether Trump appealed to people living in regions that had suffered some decline in security or population, even if voters’ relative financial standing in November 2016 was average or better.

If you access the interactive map yourself, you can do your own analysis of many interesting—and sometimes surprising—factors and see results for particular counties and regions.

The California Secure Choice Retirement Savings Program: Why pension reform turns inefficiently to the states

Posted: December 5, 2016 Filed under: Economic Growth and Productivity, Taxes and Budget 2 Comments »This post originally appeared on TaxVox.

By: C. Eugene Steuerle and Pamela Perun

Starting as soon as it can be made operational, perhaps in 2018, as many as 7 million private-sector California workers who currently have no access to a job-based retirement plan will be automatically enrolled in a state-managed savings program. The California Secure Choice Retirement Savings program will start with employee contributions of 3 percent of earnings, though the state board managing the initiative could increase the contribution rate to as much as 8 percent. While workers will be auto-enrolled, they can opt out of the plan.

The new law is an important step toward securing better retirement coverage for those who require it most. Too many people reach old age with far too little saving to meet their long-term needs.

While an interesting idea ,the plan, however, faces limits that would be better served through federal reform. For instance, companies that operate across state borders don’t want to be bogged down with 50 different sets of state regulations. In addition, federal law currently grants employee deposits fewer tax breaks than are enjoyed by employer contributions. Only federal law changes can deal with those challenges.

However, changes to federal law that reduce tax revenues may be blocked by the constraints of the federal budget process.

Here’s the rub. At the federal level, any pension reform that might succeed in securing significantly more retirement saving will be scored as losing revenue to the federal government. Big revenues. And no major tax reform or tax cut in recent years, as well as President-elect Donald Trump’s campaign tax plan, has made pension reform a priority.

Suppose, for instance, that a national reform increases net contributions to traditional retirement plans by $80 billion, or one percent of the $8 trillion of wages and salaries that workers earned in 2016. If those savers reduce their tax on new deposits by 15 percent, revenues would decline by $12 billion in the first year and by more than $100 billion over a decade, even after accounting for taxable withdrawals.

Even if we see big new tax cuts in a Donald Trump presidency, that’s a lot of money. However, state legislators do not face the same budget process constraints as federal lawmakers. They are indifferent to the effects of state law on federal revenues, and the impact of a big tax-advantaged savings plan on state revenues are relatively modest given lower state income tax rates. Hence, for now, all incentives point toward the states acting independently, inconsistently, and inefficiently in tackling our nation’s larger retirement security problems.

There are alternatives. We have proposed an alternative strategy through a federal plan that would greatly simplify current law while broadly encouraging both employer and employee contributions.

Of course, it makes some sense to let states operate as laboratories of democracy. However, the more successful this California effort and similar ones being considered in Illinois, Oregon, and Connecticut, the greater the need for the type of coordination that only the federal government can provide. Until we get our federal budget into some sort of order, however, federal reform likely will continue to be stifled. Catch 22, once again.

Photo courtesy of Randy Bayne/via Flickr Creative Commons.

Six bipartisan opportunities for president-elect Trump

Posted: November 21, 2016 Filed under: Shorts 1 Comment »This post originally appeared on TaxVox.

I have never believed that candidates should lay out detailed policy agendas in their campaigns. While broad outlines are helpful, the specifics are too complex for the stump and often unappealing to voters. So to move beyond campaign promises that seldom add up for any candidate, here is how President-elect Trump could move forward in six policy areas even while facing extraordinary budget constraints. Each issue has a framing that gives it a better chance of garnering bipartisan support.

Workers. Many workers made it clear in this election that they feel forgotten by government. While the left and right disagree over how well our government promotes opportunity for workers, they generally agree it could do better. Trump tapped into workers’ frustrations but hasn’t yet identified how to significantly help them. How about this as a start? Simply ask agencies to assess the extent to which their programs could better promote work, even when that is not their primary mission. This applies to a wide range of programs, from wage, housing, health, and food supports to how well the military helps veterans get a job.

Budget Reform. Even if some adviser tells the President-elect that there is magic money to be had through extraordinary economic growth, tackling budget shortfalls will soon become unavoidable. Never before have so many promises been made for the future, both for unsustainable rates of spending growth and lower taxes. Indeed, all future revenue growth and then some have already been committed for health, retirement, and the interest costs alone. Engaging in more giveaways only exacerbates this problem. One way to cut the Gordian knot and convince the public to buy into longer-run budget goals is to show how interest savings generated by long-run fiscal prudence eventually allows both more program spending and lower taxes than do big deficits.

International Tax Reform. If the US is going to collect tax revenue from US-based multinationals, it will need to get a handle on this issue. It makes no sense administratively to tax these firms based on the geographical location of headquarters, researchers, patents, borrowing, or salespeople. The solution involves taxing corporations less but individual shareholders more, while still engaging corporations to withhold those taxes. Any reform must limit the firms’ ability to shift income and deductions to the most tax-advantageous locations.

Individual Tax Reform. Trump could accomplish some individual tax reform by focusing less on reducing the existing $1 trillion-plus level of tax subsidies and more on limiting their automatically-increasing growth rates. He could use the revenue to either reform the tax code or better target the subsidies. For example, he could redesign housing-related tax preferences so they truly promote homeownership.

Health Reform. Conservative and progressive health experts agree that the Affordable Care Act suffers from at least two problems: It did not sufficiently tackle the issue of rising medical costs, and many people remain uninsured. Trump could generate more bipartisan support if he aims to reform the system to cover more people while generating enough cost saving to make that goal attainable in a fiscally sustainable way.

Retirement and Social Security. President-elect Trump promised to not cut Social Security benefits while Secretary Clinton said she would raise them. But raised or cut relative to what? An average-income millennial couple is scheduled to receive about $2 million in Social Security and Medicare benefits versus $1 million for a typical couple retiring today. Younger people, who often expect no Social Security benefits, seem willing to accept changes that would slow the program’s rate of growth. That’s an opening for Trump to sell the reform as a long-term effort that opens up the budget to some of their needs, such as reducing student debt, while still protecting the current elderly. For many elderly, benefits can even be enhanced through private pension reform to increase individual retirement savings and enhancing Social Security benefits for low-income retirees.

Paraphrasing Herb Stein, who was President Nixon’s chief economic adviser, “what can’t continue won’t.” And that’s true with the nation’s unsustainable fiscal path. Eventually, we will need to take the types of steps that I’ve outlined. With some creative thinking about how to newly frame important issues, President Trump could advance some real possibilities of reform despite a season of ugly campaigning.

Photo courtesy of Gage Skidmore/via Flickr Creative Commons.

Both Clinton and Trump would reduce tax incentives for charitable giving

Posted: November 7, 2016 Filed under: Nonprofits and Philanthropy 8 Comments »By: Joseph Rosenberg, C. Eugene Steuerle, Chenxi Lu, and Philip Stallworth. This post originally appeared on TaxVox.

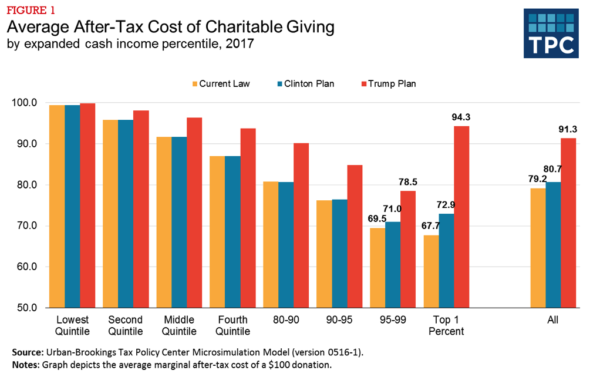

Both Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump have proposed income* tax changes that would result in less charitable giving. While the effects are indirect, the Tax Policy Center estimates that Trump’s plan would reduce individual giving by 4.5 percent to 9 percent, or between $13.5 billion and $26.1 billion in 2017, while Clinton’s plan would reduce giving by between 2 percent and 4 percent, or $6 billion to $11.7 billion.

The actual reduction in charitable gifts would depend mainly upon how responsive givers would be to smaller tax incentives. However, higher-income taxpayers would be affected the most. Lower-income households would not likely reduce giving since most do not itemize deductions today and would not under either the Trump or Clinton plans.

Figure 1 summarizes the increase in the cost (reduction in incentive) of giving under the two plans. The Clinton plan only affects the cost of giving for those in the top 5 percent, while Trump’s plan raises the cost of giving for those at all income levels.

Start with Trump, who would reduce the tax benefits of charitable giving in three ways:

First, by reducing marginal tax rates he’d increase the after-tax cost of charitable giving. If you give away $100, you don’t pay tax on that $100 of income, so the after-tax cost of the donation for someone in today’s 39.6 percent top tax bracket is only about $60—the $100 gift minus $39.60 in tax savings. But by reducing the top rate to 33 percent, Trump would raise the after-tax cost of that $100 gift to $67.

Second, by raising the standard deduction to $15,000 ($30,000 for couples), Trump would sharply reduce the number of taxpayers who itemize. People who stop itemizing can no longer deduct their charitable contributions and thus lose the tax break. In 2017, 27 million of the 45 million who now itemize would opt for the standard deduction, a decline of 60 percent.

Finally, Trump would cap itemized deductions at $100,000 for singles and $200,000 for joint filers. IRS data indicate that in 2014 taxpayers with over $1 million in adjusted gross income (AGI) deducted an average of $165,000 for charitable contributions and another $260,000 for state and local taxes. Since the state and local tax deduction alone would exceed Trump’s proposed cap on itemized deduction, many high-income taxpayers would lose their tax incentive to give to charity.

While all these changes might discourage charitable giving, Trump’s generous tax cuts would also leave taxpayers more money to give to charity. This would particularly be true for very high income households: In 2017, tax cuts for people in the top 1 percent would average more than $200,000.

Clinton’s plan would do little to change the giving incentives of taxpayers for the bottom 95 percent of the income distribution. She’d slightly increase incentives for low- and middle-income taxpayers to give to charity by boosting their after-tax incomes.

In contrast to Trump, Clinton would significantly raise taxes on high-income households. She’d impose a 4 percent surcharge on adjusted gross income (AGI) in excess of $5 million, increase capital gains rates based on holding periods, create a minimum tax of 30 percent of AGI phasing in between $1 and $2 million of incomes, and put a 28 percent limit on the value of tax benefits from deductions other than the charitable deduction. On net these not only decrease after-tax incomes, but also lead some current itemizers to take the standard deduction and thereby lose the charitable deduction. The proposal with the largest effective on giving incentives is the 30 percent minimum tax (i.e., the “Buffett Rule”), which would reduce the incentive for affected taxpayers.

Overall both candidates would reduce the tax incentives for giving to charity, probably not what either really intended.

*This analysis only includes changes in the federal income tax. Both Clinton and Trump have also proposed significant changes to the estate tax that would impact incentives to donate to charity and leave charitable bequests. Clinton’s proposal to lower the estate tax threshold and increase estate tax rates would increase giving incentives, while Trump’s proposal to eliminate the estate tax would reduce them.

The confusing debate over child tax credits and exemptions

Posted: October 31, 2016 Filed under: Children, Taxes and Budget 1 Comment »This post originally appeared on TaxVox.

In this year’s presidential campaign, Hillary Clinton’s proposal to double the child tax credit and Donald Trump’s plan replace the dependent exemption with a higher standard deduction have both helped focus attention on tax treatment of families.

Interestingly, both progressives and conservatives oppose extending preferences to children in middle and higher income families. Progressives prefer to “spend” the money on those with less income, and conservatives, especially supply-siders, believe the funds would be better used to reduce marginal tax rates.

But they confuse the two purposes of providing benefits to children. The first is a classic social welfare argument that revolves around spending to subsidize one thing (in this case, the needs of children) at the cost of higher taxes or lower subsidies for another. This is especially powerful when the benefit goes to those with the greatest needs: Concentrating a greater share of spending on lower-income people results in the greatest reduction in poverty.

But there is second goal of adjusting tax burdens for children—and it is based on a tradition that goes back at least to Aristotle: to treat equals equally under the law. Economists call it horizontal equity, but I prefer the term “equal justice.” In the tax system, this means taxing equally those with an equal ability to pay. And it should apply among all households, rich and poor alike.

This is especially important when you think about households with and without children. In almost all transfer and tax systems, benefits are adjusted for household size. For instance, the federal poverty level is about $12,000 for a one-person household and about $4,000 higher for each additional person, or about $24,000 for a four-person household. To put it another way, the guideline suggests that a $24,000 four-person family can live at the same poverty level of consumption as a $12,000 single person.

In the past, the tax system used the dependent exemption to provide equivalence for families with children. But the exemption waned in importance as per capita income rose much faster than the exemption, which for a long time was not indexed and even now is indexed only for inflation. As a result, the relative burden on households with children rose. After I revealed this in the early 1980s, President Reagan supported an increase the exemption. To believe that the current exemption of about $4,000 is the right number, one would have to believe that a couple with no children and $52,000 of income lived an equivalent lifestyle as one with $60,000 of income and two children.

More recently, Congress and presidents Bill Clinton and George W. Bush expanded the child credit in lieu of increasing the dependent exemption. That the credit has been made partially refundable and extends fairly high up the income scale implies that those expansions served both goals of spending on those in need and establishing tax parity among families of different sizes. The current exemption of about $4,000 is worth $1,000 to a family that pays a marginal tax rate of 25 percent, so the current credit of $1,000 plus the exemption grants that family about $2,000 per child in total benefits.

Whatever the right balance between the social welfare and equal justice approaches, most voters judge government on whether they think they are being treated fairly. But if children are both expensive to support and reduce a household’s ability to pay taxes, and if a welfare system separately provides supports for households with low incomes, then shouldn’t adjustment for children put explicitly in the tax system apply to most or all households? It is an interesting and important question and one for which at least politics has led elected officials to answer, “Yes.”

Photo courtesy of Ken Teegardin/via Flickr Creative Commons.

What Trump’s and Buffett’s tax returns say about how the wealthy are taxed

Posted: October 19, 2016 Filed under: Taxes and Budget 3 Comments »This post originally appeared on TaxVox.

The individual income tax has never taxed the very wealthy much. Donald Trump may have claimed huge losses starting in the early 1990s, but, like other rich investors, he wouldn’t have paid much tax regardless. Despite paying some tax, Warren Buffett’s release of his 2015 tax return affirms that conclusion.

There are two major reasons: first, paying individual income taxes on capital income is largely discretionary, since investors don’t pay tax on their gains until they sell an asset. Second, taxpayers can easily leverage capital gains and other tax preferences by borrowing, deducting expenses, and taking losses at higher ordinary rates while their income is taxed at lower rates. Such tax arbitrage is, in part, what Trump did.

To be fair, some, like Buffett, live modestly relative to their means and still contribute most of what they earn to society through charity. Some pay hefty property and estate taxes and bear high regulatory burdens. And salaried professionals and others with high incomes from work, whether wealthy or not, may pay fairly high tax rates on their labor income. Still, there are many ways for the wealthy to avoid reporting high net income produced by their wealth.

The phenomenon is not new. In studies over 30 years ago, I concluded that only about one-third of net income from wealth or capital was reported on individual tax returns. Taxpayers are much more likely to report (and deduct) their expenses than their positive income. In related studies, I and others found that rich taxpayers reported 3 percent or less of their wealth as taxable income each year.

But your favorite billionaire did not get that way by earning low single-digit returns to his wealth. Buffett’s 2015 adjusted gross income (of $11.6 million) would be around one-fiftieth of 1 percent of his wealth, which in recent years has been estimated to be near to $65 billion. Yet, over the past 5 complete calendar years, Buffett’s main investment, Berkshire Hathaway, has returned an average of over 10 percent annually.

The wealthy effectively avoid paying taxes on those high returns either by never selling assets and thus never recognizing capital gains, deferring income long enough that the effective tax rate is much lower, or by timing asset sales so they offset losses, as Trump likely has been doing to use up his losses from 1995.

When you die, the accrued but unrealized gains generated over your lifetime are passed to your heirs completely untaxed, though estate tax can be paid by those who, unlike Buffett, don’t give most away to charity.

“Tax arbitrage,” the second technique, is simple in concept though complex in practice. It allows an investor to leverage special tax subsidies just as she’d arbitrage up any investment—in this case, to yield multiple tax breaks. If you buy a $10 million building with $1 million of your own money and borrow the other $9 million, you’d get 10 times the tax breaks of a person who puts up $1 million but, because she doesn’t borrow, buys only a $1 million building.

The law limits the extent to which most people can use deductions and losses from one investment to offset income from other efforts, but “active” investors are exempt from most of those restrictions. In real estate it is quite common for the active individual or partner to use the interest, depreciation, and other expenses from a new investment to generate net negative taxable income to offset positive income generated by other, often older, investments.

The main trick is simply to let enough income from all the investments accrue as capital gains. For example, take a set of properties that generate $1 million in rents and $500,000 in unrealized appreciation. If expenses are $1,200,000, net economic income would be $300,000 ($1,000,000 plus $500,000 minus $1,200,000); but net taxable income would be a negative $200,000 ($1,000,000 minus $1,200,000) since the unrealized appreciation is not taxable income.

Real estate owners enjoy other tax benefits as well. They can sell a property without declaring the capital gain by swapping the asset for another piece of real estate—a practice known as a “like-kind” exchange. Often, when a property changes hands it ends up being depreciated more than once.

At the end of the day, tweaks to the individual income tax system, including higher tax rates, are unlikely to increase dramatically the taxes paid by the very wealthy. Instead, policymakers need to think more broadly about how estate, property, corporate, and individual income taxes fit together and how to reduce the use of tax arbitrage to game the system.

Photo courtesy of Stuart Isett/via Flickr Creative Commons.

Social Security must be fair for everyone, not just retirees

Posted: October 11, 2016 Filed under: Aging, Economic Growth and Productivity 6 Comments »A version of this post originally appeared on The Washington Post.

+What should the next president do to make Social Security more sustainable?

No one should assess Social Security policy in isolation. What is fair in Social Security must relate to what is fair for the national budget as a whole.

Congressional Budget Office projections indicate that by 2026 we’ll be 21 percent richer, and that tax revenues will rise at a slightly higher rate. That means we stand before an ocean of opportunity. But of the expected $850 billion in additional real revenues, about 150 percent (or about $1.3 trillion) is committed entirely to increasingly expensive payments to Social Security, health care and interest on the debt. And as a result of these commitments, almost anything that represents investment — in our children, infrastructure or the basic functions of government — takes it on the chin.

[The problem with Social Security lies in its history]

Even as revenues grow, the number of workers available to pay for Social Security benefits is falling rapidly, meaning that either benefits must be cut, taxes increased, or both. Every delay puts more of the cost on the young.

Social Security maintains a design built around an economy and family structure of the past. People aged 65 now live about six years longer and retire even earlier than they did in 1940 when the system first paid benefits. That means families like Clinton’s, Trump’s and mine will be getting hundreds of thousands of dollars more in lifetime benefits than they would have when the system was first created, while many future elderly will still be left in poverty.

So what must be done? Slow down and reorient the growth in benefits scheduled for future retirees. A typical couple retiring today gets more than $1 million in lifetime Social Security and Medicare benefits; millennials are unrealistically scheduled to get $2 million. That growth can be slowed without being stopped and shifted more toward those who are truly old with low- to moderate-incomes. While Social Security’s long-recognized shortfalls inevitably mean someone must pay, those with above-median incomes are the ones with the money.

Still, no Social Security benefits need to be cut for those currently retired. To do better for those elderly with median or lower lifetime incomes, we should raise minimum benefits and give credit for raising children. We should also fix absurd rules around spousal and survivor benefits and other sources of inequity.

[Social Security needs to return to its anti-poverty roots]

The current system discourages work in late-middle age, something that is no longer easily affordable and which reduces economic growth, personal income and tax revenues. Congress should reduce Social Security’s natural disincentives for work both by adjusting the retirement age as we live longer and saving a larger share of lifetime benefits for later ages, when health needs rise and work is less possible. As lifespan increases, Social Security now promises a typical newly retired couple aged 62 an average of more than 28 years of benefits (today, one of them is likely to make it to 90 years of age). That’s more than enough; there are greater societal needs than the desire for more retirement years.

Finally, the tax issue. While some broadening of the Social Security tax base is possible, government needs to concentrate on raising revenue for high priorities apart from Social Security: our growing national debt, and vital investments such as education, infrastructure and support for working families. Campaigns are about giveaways, but true reform requires looking at what must be done and how, whether we want to or not.

Photo courtesy of The Social Security Administration, Public Domain.

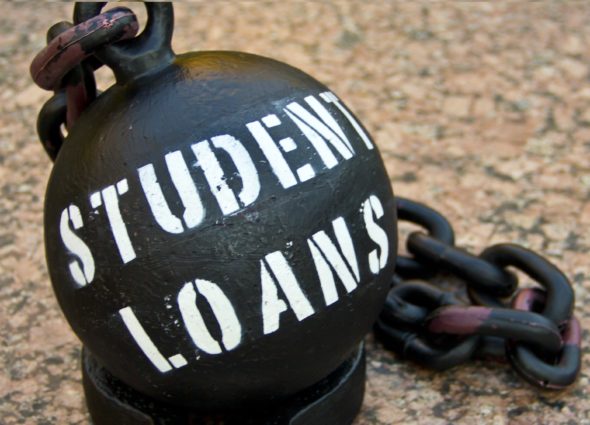

STUDENT DEBT: THE MACRO QUESTION

Posted: October 5, 2016 Filed under: Economic Growth and Productivity 5 Comments »The 2016 presidential election has made student debt a national issue. Two just-released books, one by Sandy Baum and one by Beth Akers and Matt Chingos, have done a great job of identifying the real problems with student debt, while debunking much of the rhetoric that tends to identify wrong problems and come up with wrong solutions. I highly recommend the books, though I am hardly unbiased since Matt and Sandy are colleagues of mine.

By focusing on the real risks associated with the current system, the authors emphasize that we must pay attention to who acquires the debt and who benefits from it. For instance, future doctors and lawyers with high returns to postgraduate education acquire some of the highest levels of student debt. Akers and Chingos emphasize that over 40 percent of student debt is held by those in the top 20 percent of the income stratum. Thus, simply eliminating student debt would help the highest income borrowers most.

Sandy Baum focuses on designing proposals that would prevent so many at-risk students from borrowing for programs unlikely to serve them well. She especially discredits proposals that provide the most assistance to those who are actually in the best position to repay their loans. One example of how all this plays out was shown earlier by some other colleagues: blacks as a group, who are less likely to come out of college with a degree, end up with higher average student debt than whites.

Here I wish to address a more macro question: whether this shift toward higher student debt represents just one more way that government has disinvested in the economy. As students accumulated $1.3 trillion in debt, did government make an equivalent increase in investment in what economists often call “human capital”? Or did government simply shift additional burdens onto these students with few or no significant gains in educational achievement nationwide? Or something in between?

When we look at budgets as a whole, both federal and state, it’s quite clear how resources are being shifted. Average tax rates are about where they have been, maybe a touch higher. Taxpayers may have gotten a break for a while as rates went down a bit and then back up a bit, but that’s not the main story. Both federal and state budgets have adopted huge spending increases for retirement and health care. States have also put a lot more into prisons, while the feds have put much more toward interest costs, though offered a reprieve—if one can call it that—by a weak worldwide economy that has led to low interest rates.

Clearly, a smaller share of revenues and incomes goes for education—not just higher education, but primary and secondary education as well. Almost anything that might qualify as investment, such as infrastructure, has also seen a downturn.

Taking the budget as a whole, therefore, it’s hard to avoid the conclusion that the net effect of federal and state policies, of which student loans become merely one example, has been a disinvestment in the economy as a whole.

This raises an additional issue for those assessing programs by comparing benefits to costs. In the case of student loans, if more borrowing on average increases human capital by more than the value of the loans, we would say it was worthwhile for individuals to take out those loans. Correspondingly, if we were replacing a system with less education and no loans with one that on net created more assets than debt, we would likely conclude that the shift was worthwhile societally, not just individually. However, starting from a society that had financed education more directly, the student loan policy may be a failure.

Put another way, the starting point matters. In this arena and others we usually want government to increase net investment, as well as improving the allocation of funds so as to garner the highest returns on the investment, and we need to figure out the effect across the entire balance sheet of assets and liabilities. The individual perspective compares the personal increase in assets with the personal increase in borrowing and asks whether enough people come out ahead that society is better off. But if the additional loans don’t finance an increase in education societally, whether because some students don’t attain degrees or others don’t acquire any more education than they would have undertaken anyway, then we must ask what we got for our money.

If this debt policy additionally discourages risk taking and marriage after education, then all this debt may even reduce investment over time in education, businesses, and homes combined. Unfortunately, I think this has been the most likely outcome of recent policy. Even the creative reforms that Baum, Akers, and Chingos recommend won’t restore those past losses, though they may help minimize them in the future.

Whatever your take on this issue, this presidential campaign makes clear that higher education reform very likely will be on the national agenda in the next year or two. The Baum and Akers-Chingos studies should be required reading for anyone undertaking that reform.

Photo courtesy of Andrew Bossi-Flickr.