Three Largely Ignored Tax Policy Issues When Taxing The Wealthy

Posted: January 10, 2020 Filed under: Uncategorized Comments Off on Three Largely Ignored Tax Policy Issues When Taxing The WealthyThe current debate over wealth taxes mostly focuses on whether the very rich are undertaxed, but gives little attention to the most efficient and fairest ways to tax them and capital income more generally. Here are three specific questions that any well-designed effort aimed at raising taxes on the wealthy should answer:

- How do the changes address double taxation?

- Is there any reason why gains unrealized by time of death should be subject to income tax, as under current law, only for heirs of decedents who die with money in retirement accounts?

- When is the best time to tax wealth and/or returns from capital?

Double Tax Issues

The wealthy already may be taxed through corporate income taxes, individual income taxes, and estate taxes. Few believe these taxes combine efficiently to raise revenue or that the burdens are distributed fairly. Some individuals are subject to all of these taxes on their capital income, some none. These double tax issues could become magnified should a new wealth tax simply be grafted onto the existing tax structure.

Consider how the corporate tax can combine with the individual income tax (both statutory income tax rates and a “net investment income tax”) to create a double tax. For now, I’m ignoring the estate tax. A new wealth tax can create a triple tax for the stock owner of a corporation that recognizes its income currently and then pays the remaining income (after corporate income tax) out as dividends. Suppose the return on capital is 6 percent, then a 2 percent wealth tax is roughly equivalent to a 33 percent income tax rate on that capital income. However, that wealth tax can combine with a 21 percent corporate income tax rate and a potential individual income tax rate of 23.8 percent (the 20 percent tax on qualified dividends plus the 3.8 percent net investment income tax). After taking into account interactions, the total tax rate on that return is still over 70 percent, well above the current nearly 40 percent potential combined corporate and individual income tax rates.

By contrast, the partnership owner of real estate who uses interest and other costs to completely offset rent revenues, while earning a 6 percent net return entirely in the form of capital gains on the property, owes no corporate or individual income tax currently, and simply pays the 2 percent wealth tax, for a combined tax rate of 33 percent on the income generated by this property.

Double taxes (or triple taxes) aren’t new by any means. What to do about them depends upon the purpose of those taxes. But at very high levels of assessment, where the effective income tax rate can approach or exceed 100 percent, this issue becomes a lot more important. And, as far as I can tell, almost none of the proponents of a wealth tax have dealt with or even discussed it.

Taxation of Gains Accrued at Death

Among the issues that arise in assessing higher taxes on the wealthy is whether Congress should continue to forgive income taxes on gains accrued but not yet taxed by time of death because the underlying assets have not been sold. Both the holder of a regular IRA account and the owner of corporate stock with accrued capital gains have income earned during their lifetime but not yet taxed by time of death. Yet only the latter gets permanent forgiveness of the tax, because the heir’s basis in the asset is “stepped up” to the value at the time of the original owner’s death. In contrast, heirs of an IRA or other retirement account must over their lifetimes pay tax on all gains accrued by their deceased benefactors. (In fact, Congress just passed a new law requiring heirs to recognize income and pay income tax over ten years on inherited retirement accounts.) Now I recognize that the two cases are not exactly equivalent when IRA owners get an extra tax break by deferral of taxes on their wages (because the contribution to a traditional IRA is deductible). But I suggest that the same holds for many wealthy taxpayers for whom the returns to wealth often derive from returns to labor and entrepreneurship for which tax was also deferred. Why not create greater parity between households with IRAs and more wealthy households who accrue their untaxed capital income outside of retirement accounts?

Timing of Taxation on Returns from Wealth

Regardless of the level of tax assessed on the wealthy, when to tax them raises very important efficiency issues. See my earlier two-part discussion here and here. Among the concerns that carry over to wealth taxation, successful entrepreneurs become wealthy mainly by earning a very high rate of return on their business assets and human capital, then saving most of those returns within the business. Because the societal returns to most great entrepreneurial ideas dissipate as the new idea ages, and the skills of the entrepreneurs often don’t pass onto their children, rich heirs tend to generate lower rates of return for society, not just themselves, than their entrepreneurial forebears. Thus, it may be better for society to collect tax on the accumulated unrealized gains at death rather than taxing them during life and reducing the entrepreneur’s wealth accumulation. As Winston Churchill once stated, “The process of creation of new wealth is beneficial to the whole community. The process of squatting on old wealth though valuable is a far less lively agent.”

Answering the three questions raised at the beginning of this post can help channel efforts to raise—or for that matter, lower—taxes on the wealthy more efficiently and equitably.

This column first appeared on TaxVox on January 8, 2020.

On Giving And Getting In This And All Our Holy Seasons

Posted: December 31, 2019 Filed under: Uncategorized Comments Off on On Giving And Getting In This And All Our Holy SeasonsI must confess my misgivings about much that surrounds Christmas, Hanukkah, Kwanzaa and other celebrations near the Winter Solstice. I certainly applaud and am rejuvenated by the spiritual preparation, gathering of family and friends, and joy in a season that extends from Thanksgiving through the New Year. Most of all, hope rises as our souls reflect on how powers far beyond our own mortal beings have made us not only beloved, but capable of holiness. As one song reminds us, “the weary world rejoices, for yonder breaks a new and glorious morn.”

But has the soul really “felt its worth?” Or has it been overwhelmed by the commercialism that has increasingly dominated the season, from the first Black Friday offerings that begin on Thanksgiving evening? Is that what our prayers of thanks that day have come to? A curious order surrounds those first days of this extended season: first, Black Friday, then Cyber Monday, then Giving Tuesday—the last fairly new, and certainly last chronologically and monetarily in the pecking order. Getting comes before giving.

As wonderful as the outreach efforts of our churches and synagogues can be in this holy season, and our mosques and temples in their own seasons of hope, in some ways getting before giving still applies even there. No matter how rich our place of worship and its members, the collections throughout the year almost always go first and first and foremost to our internal needs, our club membership, and, then and only on occasion to needs other than our own. The first collection is for us, the second—if it occurs—for them. The poor box usually sits at the back of the church. Twice during my life, I offered two different churches a guarantee that money for their internal needs would not go wanting or decline for a couple of years if they would experiment with putting the needs of others on a par with our own. Good people, the members of the church councils couldn’t figure out how to reset priorities that much; they found few or no models to follow.

While our religions teach us that all seasons are holy, the data don’t support that recognition. No matter how much richer we become than previous generations, we in the U.S. don’t give away more than about 2 percent of our income; most other nations give even less. Similarly, when my co-authors and I look at data on giving by those with significant amounts of wealth, none—not even those with more than $100 million of wealth—gives away more than half of 1 percent of its wealth each year, though some do become more generous at time of death, when the hearse lacks a luggage rack.

Why such reluctance to give up some significant share of our wealth no matter how much we have? I have become convinced that doing so threatens our options in life in ways that modest giving out of income usually does not. We can get a warm glow feeling by participating in giving rituals, as during the holiday season, but very few of those rituals ask us to change our basic way of living.

Since this column regularly centers on public policy, I can’t help but relate this imbalance between getting and giving to our political debates. World War II left in its aftermath appreciation for sacrifice, perhaps symbolized most by John Kennedy inaugural claim in 1961 to “pay any price, bear any burden, meet any hardship” for the cause of liberty. Even by then, however, we had begun our long slide downward from the peak Marshall plan years, when we contributed about four percent of our national income for foreign aid, to a level today only about one-eighth that size, measured relative to our income.

More than a Trumpian phenomenon, politics in the modern age has long centered on what we get. Candidates tell us that we represent suffering, oppressed, citizens who must be favored with more benefits or fewer taxes. Occasionally we might have to pay a bit more to get a lot more, but usually not even that will be required. Anyway, fortunately, money grows on fiscal trees or within fertile Federal Reserve vaults. Mainly, however, we don’t get enough because of, you know, them. Some claim our society’s problems derive from immigrants from “shithole countries” or billionaires in “wine caves,” and others who align themselves against us by joining with liberals or conservatives intent upon destroying our democracy. So, when bad things happen, “they,” not “we,” bear no responsibility for their happening, much less for fixing them.

As voters, we know that any politician who lays out any sense of shared responsibility for giving, not just getting, cannot get elected. Salvation for true believers in one political party or another lies simply in blaming those outside our self-righteous clan. The rest of us simply hold our noses and try to figure out which candidates might do the right thing despite their campaign rhetoric.

Still, life stirs beneath the frozen ground, and soon new growth offers wonders and opportunities never before seen. My prayer is that we and our neighbors become twice blest, as givers and receivers, as we find new ways to give and build on that new life in all our holy seasons to come.

Paul Volcker Taught Us How Tax And Monetary Policy Can Work Together To Enhance Growth

Posted: December 17, 2019 Filed under: Uncategorized Comments Off on Paul Volcker Taught Us How Tax And Monetary Policy Can Work Together To Enhance GrowthThe recent passing of former Federal Reserve Chair Paul Volcker serves as an important reminder of his critical role in ending stagflation in the late 1970s and early 1980s. But while most attention is being paid to how his aggressive efforts to raise interest rates broke the back of accelerating inflation, Volcker’s interest rate hikes served another key purpose: by restoring positive costs for borrowing, they helped channel funds away from investments that produced low or even negative economic returns to society. In most of the 1980s and 1990s, as inflation fell and Congress reduced marginal tax rates, the economy began a period of significant productivity growth.

Volcker’s experience serves as an important reminder that monetary and fiscal or tax policy can do more than provide stimulus and at times help avoid recession. These policies often subsidize investors who use borrowed dollars and may distort investment incentives. In particular, monetary policy can lower borrowing costs (and lower interest rates can disadvantage savers), while tax policy can encourage leverage and discourage equity investment by allowing borrowers to deduct from their income more than the real cost of interest payments.

Here’s a simple example of how monetary and tax policy work in combination: Imagine a world where the interest rate is equal to the inflation rate. The real or inflation-adjusted interest cost for borrowing is then zero, yet the borrower gets to deduct full nominal interest costs, so the after-tax real cost of borrowing would be negative. (Technically, net after-tax, after-inflation borrowing costs become negative when the interest rate is less than the inflation rate divided by one minus the tax rate.)

Such was the case in the late 1970s and early 1980s, when top corporate income tax rates and top individual tax rates on capital income were about 50 percent and annual inflation exceeded 10 percent. Approximately speaking, if a corporation borrowed at 20-percent nominal interest rate and took a tax deduction at a 50 percent tax rate and adjusted for inflation, its real after-tax interest rate would be below zero. Since interest rates faced by actual corporate borrowers were often well below 20 percent, tax shelters of all sorts proliferated. Investments in unproductive capital became profitable. Stagnation then accompanied high inflation during those years, as I described in a book on the topic. Whatever cash flow problems Volcker’s interest rate policies temporarily caused to businesses and individuals, they also forced investors to rethink investments in tax shelters and to make productive investments that would earn positive real private returns.

What about today? Even though inflation remains low, businesses still get a tax subsidy for borrowing. If the annual inflation rate is 2 percent and a corporation’s borrowing cost is 4 percent, for instance, the corporation still can deduct twice its real interest costs. But in this example, corporate income tax rates would have to be above 50 percent for the real after-tax borrowing cost for the firm to be negative. However, in some foreign countries, nominal interest rates have turned negative, while in the U.S. the federal funds rate—the cost of borrowing by banks—is much closer to zero, after inflation. This means that some borrowers already may be facing negative real interest rates.

As for today’s tax policy, whatever its defects, the Tax Cut and Jobs Act (TCJA) sharply cut corporate income tax rates and effectively reduced the tax subsidy for corporate borrowing.

This feature strengthens monetary policy. If inflation accelerates in the future, the Fed won’t need to increase interest rates as much to dampen that inflation because the real after-tax cost of borrowing will remain positive. Volcker’s interest rate adjustments, for instance, could have been smaller and achieved much the same results had tax rates then been lower in the late 1970s.

That doesn’t mean that the U.S. has completely removed distortions created by our tax and financial systems. Under TCJA, borrowing by noncorporate businesses remains more subsidized than for corporations (because top individual income tax rates are higher than the corporate income tax rate). This means that the noncorporate share of business borrowing is likely to rise as the corporate share falls, all other things being equal.

Of course, high corporate tax rates and low real interest rates are not the only ways that government policies encourage excessive borrowing. Bankruptcy law protects individuals and business owners from bearing the full costs of their mistakes, not only for all assets they own, but often for each individual business. Banking laws, deposit guarantees, and implicit promises to limit bank failures further protect banks and their borrowers, while encouraging leverage. In combination with today’s low interest rates, these various policies help create negative expected real interest costs for many borrowers.

Thus, while some of these policies may encourage investment and capital formation and help the economy grow, over the long run they still can fuel excess leverage, consolidation of industries, tax sheltering, and (still) too big-to-fail banks.

Bottom line: despite lower rates of inflation today, we need to take seriously the public finance lessons from the Volcker era. While recent corporate tax rate cuts will reduce subsidies for borrowing and have some significant positive impacts on corporate finance, the nation’s borrowing juggernaut will remain well fueled and continue to weaken future economic growth by encouraging investments with low or negative real private economic returns.

This column first appeared on TaxVox on December 16, 2019.

Government Trust Funds Are Selling America Short

Posted: December 12, 2019 Filed under: Uncategorized Comments Off on Government Trust Funds Are Selling America ShortFederal lawmakers have found many ways to shift the responsibility for today’s spending to tomorrow’s taxpayers. But among the most important is their habit of abandoning the fiscal discipline that should accompany government trust funds.

A new bill, the Bipartisan Trust Act, may focus new attention on this issue. Sponsored by Senators Mitt Romney (R-UT) and Joe Manchin (D-WV), Representatives Mike Gallagher (R-WI) and Ed Case (D-HI), and a bipartisan group of other members of Congress, the proposal would create commissions to recommend changes whenever a trust fund approaches insolvency and has insufficient assets to pay its bills.

The federal government operates a half-dozen major trust funds as well as a number of smaller ones. The biggest, of course, are for Medicare and Social Security, but it also operates trust funds to pay for highways, airports, military and federal civilian retirees, and unemployment insurance.

These funds implicitly obligate the government to serve as trustee for the taxes and payments collected specifically for those programs. But many trust funds chronically fall short of money and rely on the federal general fund to pay obligations.

Unlike privately established trust funds to support specific activities, where assets are accumulated to pay future obligations, programs such as Social Security and Medicare mainly operate through pay-as-you-go financing. The government immediately disburses almost all the dedicated taxes paid by current workers to recipients, generally from older generations; current workers receive benefits by depending upon succeeding generations to pay over the necessary taxes.

For decades, government has allowed the “trust fund” label to perpetuate the myth that the payroll taxes current workers pay are being held in reserve for their own Social Security and health benefits in retirement. While that is largely untrue, it does not exempt policymakers from their obligation to protect future generations by requiring that over time cumulative spending be covered by cumulative dedicated taxes.

When Franklin Roosevelt’s administration was drafting the Social Security bill in 1935, the president opposed an early version that would have left the fund in deficit by 1980. Sylvester Schieber and John Shoven, report on his objection, as recounted by his labor secretary Francis Perkins:

“This is the same old dole under another name. It is almost dishonest to build up an accumulated deficit for the Congress of the United States to meet in 1980. We can’t do that. We can’t sell the United States short in 1980 any more than in 1935.”

Unfortunately, Congress largely has abandoned this Rooseveltian degree of fiscal prudence.

Medicare may be the most striking example of this abandonment. Medicare Part A hospital insurance was funded through a piece of the Social Security payroll tax. But Congress did not want to raise taxes even more to fund Part B that covered doctors’ fees and other outpatient care. So, it funded Part B through general revenues, supplemented by premiums. A half-century later, it did the same thing for Part D drug insurance.

Yet, Congress still applied the label “trust funds” to these programs even though effectively they simply transferred general revenues to doctors, drug companies, and other health providers.

By doing so, Congress turned the public trust fund concept upside down.

Instead of limiting benefits to the amount of dedicated taxes collected on behalf of the program, Congress structured the programs to pay out open-ended benefits that generally rose with costs. Any shortfall would be taken from general funds, often financed through borrowing.

Meanwhile, even for Part A of Medicare and Social Security cash benefits, Congress historically set the tax rate too low to cover future liabilities even on an annual basis, leaving to future elected officials the responsibility to raise taxes or reduce benefits.

Then Congress played accounting games. As the Part A trust fund dwindled, Congress shifted some inpatient costs to Part B. When Social Security’s Disability Insurance trust fund was about to run out of money, Congress transferred funds from the Old Age and Survivors Insurance trust fund, leaving to a future Congress how to fill that program’s growing fiscal hole.

This takes us back to the Bipartisan Trust Act. If it becomes law, one can only hope that its reforms establish new standards for trust fund financing, at a minimum following Roosevelt’s dictum to not “sell the United States short” by requiring future taxpayers to pay even higher tax rates for obligations being incurred today.

This column first appeared on TaxVox on December 3, 2019.

How Norms and Laws Might Further Limit Executive Branch Influence Over Investigations

Posted: October 18, 2019 Filed under: Uncategorized Comments Off on How Norms and Laws Might Further Limit Executive Branch Influence Over InvestigationsRecent stories in the news raise important questions about the ability of government to impose constraints on abusive government investigations.

I’m not here to judge the credibility of the allegations that President Trump used his office to encourage foreign governments to investigate Joe Biden’s son or that a Treasury Department official interfered with audits of the President’s or Vice-President’s tax returns. Instead I want to turn to the history of the IRS to draw out important lessons in how issues such as these have been addressed in the past and then use that information as a base from which Congress can consider further guardrails to prevent future abuses. Among the possibilities are to further require, not simply offer protection for, whistle-blowing.

The first line of defense, of course, is the integrity of public officials themselves and the norms they help create. More than four decades ago, White House Counsel John Dean gave IRS Commissioner Jonnie Mac Walters a copy of President Richard Nixon’s “enemies list” that included about 200 Democrats whose tax returns he wanted audited. Walters and Treasury Secretary George Schultz agreed between themselves to throw the list into a safe and forget about it.

When Walter’s successor, Donald Alexander, discovered that a handful of IRS staffers had been assigned to investigate the returns of about 3,000 groups and 8,000 individuals, often because of their political views, he disbanded the group. Those of us who knew him are aware of how proud he was for standing up to the White House and protecting the integrity of the IRS.

Interestingly, it wasn’t until 1998 that Congress turned this normative prohibition into law. The Taxpayer Bill of Rights, part of a bill that restructured the IRS that largely came out of a Republican-led Senate, said this:

It shall be unlawful for any applicable person to request, directly or indirectly, any officer or employee of the Internal Revenue Service to conduct or terminate an audit or other investigation of any particular taxpayer with respect to the tax liability of the taxpayer.

Congress said applicable persons include the President, Vice President, and any employee of the White House and most Cabinet-level appointees.

The Taxpayer Bill of Rights made clear that Congress was concerned about protecting potential victims, not just punishing offenders. Each individual is entitled to equal justice under the law, and Congress determined that politically motivated investigations violated that justice standard. The Joint Committee on Taxation staff in their explanation of the law listed another reason: The concern that improper executive branch influence could have a “negative influence on taxpayers’ view of the tax system.”

The 1998 law not only prohibited this improper influence, it explicitly required disclosure:

Any officer or employee of the Internal Revenue Service receiving any request prohibited by subsection (a) shall report the receipt of such request to the Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration.

It says “shall.” Disclosure is not optional. Congress made it a crime for “any person or employee of the IRS receiving any request” to fail to report it, whether it was direct or indirect. No explicit quid pro quo necessary to get the Inspector General involved.

In the current context, the statute is clear: Anyone in the IRS, including the Commissioner, must report any improper attempt by high-level executive branch officials at interfering with audits of the president and vice-president or anyone else.

Thus, there are at least five bulwarks against inappropriate political interference with IRS investigations.

- Appointment of professionals and strong leaders who will protect the integrity of their offices;

- Social norms that most politicians would feel reluctant to violate;

- Penalties on those who interfere in the investigative process;

- A requirement that those receiving the unlawful request report it;

- Penalties on those who fail to report the request (to go along with the penalties on the requestor).

No law is perfect, and a president or other person could find their way around current law or protect others who abuse it. Still, norms and laws do constrain the quantity and extent of bad actions. So does a transparent disclosure system for revealing abuses. Even if some figure out how to violate legitimate boundaries, fences still can limit trespassing.

As citizens, and taxpayers, we all have rights to equal justice. Enforcing those rights often requires laws, as well as norms. The development of law protecting taxpayers against abuses of the IRS audit process may set an example for Congress to apply to elected officials, officers, and employees beyond the IRS and to investigations undertaken by other agencies.

This column first appeared on TaxVox on October 15, 2019

Multi-Trillion Dollar Fiscal and Monetary Gambles

Posted: September 3, 2019 Filed under: Uncategorized Comments Off on Multi-Trillion Dollar Fiscal and Monetary GamblesUnder pressure from President Trump and worried about a worldwide economic slowdown, the Federal Reserve recently cut short-term interest rates. By continuing to push rates down, the Fed may be doubling down on a $25 trillion gamble with future costs yet to be covered.

At the same time, the Trump Administration reportedly is considering tax cuts—that would add the deficit– to boost the economy in the short term. It too may be making another giant bet, with interest and debt repayments to be made by future taxpayers.

To understand why, keep in mind that what matters when government tries to spur economic growth is not the current rate of change in fiscal or monetary policy, but the change in the rate of change. For instance, the short-term economy grows (all else equal) when the Fed accelerates the pace of growth in the money supply or when Congress increases Treasury’s rate of borrowing by cutting taxes or increasing spending. Acceleration spurs growth, deceleration dampens it.

Suppose federal borrowing rises to 4 percent of national output. In a steady economy, merely keeping borrowing at 4 percent in future years adds no new stimulus. But raising the deficit to 5 percent of GDP, or more than $1 trillion today, would stimulate growth through a larger budget deficit relative to the size of the economy. To keep the wheel spinning, Congress needs to borrow ever greater amounts—increasing the rate of change in debt accumulation. In an actual downturn, that additional borrowing would be on top of the old rate of borrowing plus the new borrowing forced by the decline in revenues—which is why many economists fear that each new fiscal gamble in good times increasingly deters future fiscal responses to a recession.

The same goes for monetary policy. Though not the only factor involved, the extraordinarily low short-term interest rates the Fed has maintained over recent years has helped promote an increase in the rate of wealth accumulation. The measured wealth of households rose from a long-term average of less than 4 times GDP to well over 5 times GDP. While that ratio fell closer to its historical level in the Great Recession, it has since risen to an all-time high. That’s about a $25 trillion increase that, if history is a guide, could become a $25 trillion loss if the ratio of wealth relative to income merely reverts to its average.

All those additional budget deficits and increases in household wealth, in turn, spur consumption. For instance, a recent NBER working paper by Gabriel Chodorow-Reich, Plament T. Nenov, and Alp Simsek suggests that a $1 increase in corporate stock wealth increases annual consumer spending by 2.8 cents. Building on that estimate, conservatively suppose each dollar increase in all types of wealth boosts annual consumption by about 2 cents. That would mean that a $25 trillion wealth bubble would spur this year’s consumption by about $500 billion, or about 2.5 percentage points of GDP more than had wealth simply grown with income.

What do you do if you’re Congress and an economy operating at full employment starts to slow down a bit? To spur the economy, you need to increase budget deficits at an even faster rate than before. If you’re the Fed thinking about sustaining or increasing consumption based on the wealth effect, then you try to maintain or increase the wealth bubble by not allowing housing or stock prices to fall.

How does this end? Science tells us: Not well. For instance, imagine an insect species identifies a new food source. The insect population will multiply rapidly until the demand from its accelerating birth rate outstrips the supply of food and the insect population crashes.

The economist Herb Stein described this phenomenon as simply and clearly as possible: “If something cannot go on forever it will stop.”

Our fiscal situation may not be that dramatic, but large budget deficits can lead to economic stress, and eventually, a crash. That has been the fear historically, though the recent experience of easy money across the globe, very low interest rates, and associated wealth bubbles may have offered a reprieve of sorts. However, interest rates that turn negative on an after-inflation, after-tax basis can lead to unproductive investments, which, in turn, can slow real economic growth even without a crash.

The modern economy may protect us in some ways. For example, the flow of international trade may mitigate economic slowdowns in any one region. And a service economy may not face some of the tougher business cycles that threaten an industrial one. But none of these factors overcomes Stein’s Law: Fiscal and monetary policy cannot always operate on an accelerating basis. To maintain the flexibility to accelerate sometimes, they must decelerate at other times.

Right now, we’re living with a $25 trillion wealth gamble by the Fed and trillion-dollar deficit bets by the Congress and the President. We’ve yet to see how it all ends and how the bills will be paid. How safe do you feel that your winnings will cover your share of those bills?

This was originally posted on TaxVox on August 29, 2019.

How Much State Spending Is On Autopilot?

Posted: August 1, 2019 Filed under: Uncategorized Comments Off on How Much State Spending Is On Autopilot?This column was co-authored with Tracy Gordon and Megan Randall and was first published on Tax Vox.

In his 2005 State of the State address, California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger sounded like he was being chased by the new Terminator T1000: It is on automatic pilot.

It is accountable to no one. Where will it all stop? How will it stop unless we stop it?

He was not talking about a threatening cyborg but rather a school funding formula added to the California constitution by ballot initiative (Proposition 98) backed by teachers and other public school advocates.

Governors and lawmakers have long decried constitutional and statutory formulas, federal grant requirements, and court rulings that limit how they can spend money. But how much of a state’s spending is actually out of current governors’ and legislators’ control? How much have past budget decisions limited states’ “fiscal democracy”?

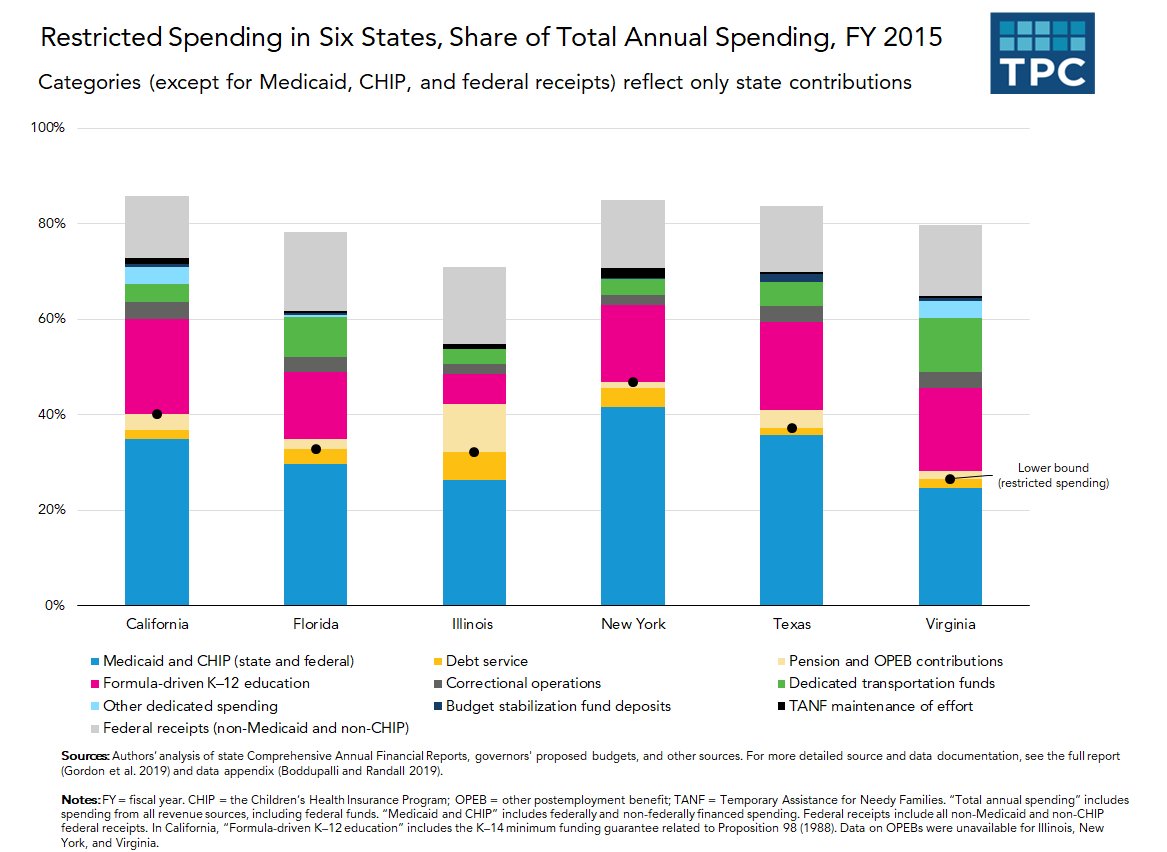

Focusing on six states (California, Florida, Illinois, New York, Texas, and Virginia), we estimated that anywhere from 25 to 90 percent of budgets may be predetermined. For example, at the high end of our estimates, 86 percent of California’s spending was potentially restricted in 2015. At the low end, only 40 percent of California spending was restricted in that year.

Why the big range? Because spending constraints fall along a continuum of flexibility, and there is no consistent definition of mandatory spending across states. The federal government explicitly defines “tax expenditures” and “mandatory spending” in law and reinforces these concepts through the annual budget process. But most states do not rigorously or transparently assess the long-term cost of those tax breaks and spending programs that are either fixed in size or grow automatically without policy changes.

All states treat debt service and Medicaid as required spending. But many are more flexible when it comes to how they treat spending subject to federal rules, state revenue earmarks, or court decisions. Still other spending may be tied to changes in caseloads and costs. For example, state contributions to public employee pension plans and the portion of K-12 education funding determined by a fixed formula may be considered restricted. But it depends on an individual state’s constitution and any court decisions that apply.

Then there’s politics. A consistent theme in our interviews with state budget officials was “everything is flexible, especially in a crisis.” But even if the law technically allows it, elected officials may be reluctant to take the heat for changing the rules, reducing built-in program growth, or raising taxes. For example, few elected officials want to be seen as cutting K-12 education, although failing to budget for forecasted enrollment and cost increases happens all the time.

In all, we discovered that governors and legislators must weave their way through a multifaceted and complex maze of restrictions, not just to adopt a budget and make appropriations, but also to set new priorities.

In the end, something’s got to give. Our results suggest that when so much of state budgets are fixed, programs such as poverty assistance or higher education get squeezed. State leaders also may be reluctant to undertake new initiatives, such as expanding pre-K education, that require either new money or shifting funds from more protected programs. State budget restrictions may beget more restrictions, as advocates push lawmakers to lock in spending or earmark revenues for their favored programs.

How can elected officials break this cycle? They could start with more disclosure. Public budgets should show by program the inflation-adjusted cost of maintaining existing services given projected caseload and price increases and project how that cost changes over time. Although state budget officials routinely assemble the information they need for such current services budgets, few prepare multiyear projections, use them as a baseline from which to assess new policies, and make them public.

Only by consistently examining budget commitments over time can governors, legislators, and voters understand how much flexibility state governments have to meet short- and long-term priorities, plan for the future, and, most importantly, respond to new challenges and opportunities.

The SECURE Act Falls Far Short Of Enhancing Retirement Security

Posted: July 9, 2019 Filed under: Uncategorized Comments Off on The SECURE Act Falls Far Short Of Enhancing Retirement SecurityThis column first appeared on TaxVox.

Congress seems about ready to pass a package of about 28 retirement and pension plan changes the House calls the SECURE (Setting Every Community Up for Retirement Enhancement) Act. This bill demonstrates bipartisanship, generally good policy, and a willingness to finance its tax cuts with some offsetting tax increases, features that have been in short supply in Congress.

Still, despite its title, the SECURE Act only modestly enhances retirement security. Congress has yet again failed to tackle broad–and badly needed–reforms.

The bill’s most costly provision increases from 70 to 72 the age at which individuals must start to take required minimum distributions (RMDs) from retirement accounts. This is a modest but worthy adjustment since people are living longer than in 1974 when many of the current RMD rules were written. By 2029, this change would cost about $900 million per year.

The bill’s second most-costly provision would make it easier for employers to organize retirement plans covering workers from multiple firms. This should make it easier for smaller firms to offer retirement benefits to their employees, expanding coverage somewhat.

The bill’s biggest revenue-raiser requires children and other beneficiaries to take distributions from their inherited retirement accounts more quickly, thus forcing them to pay taxes that they otherwise would defer. Curbing a tax break that does nothing to enhance the retirement security of deceased persons who did not spend all their pension wealth would generate about $2.5 billion by 2029.

Still, the bill accomplishes very little for the population as a whole.

First, the bill tinkers with several provisions of pension law, worth a few billion in tax subsidies but is likely to have little effect on overall retirement savings in the US. The total amount of tax benefits for pension and retirement savings was about $250 billion in 2018. By 2029, annual Social Security costs are projected to increase by about $500 billion relative to 2018 in inflation-adjusted 2018 dollars. And the total value of pension and retirement accounts of all types in the US is about $25 trillion.

Second, these changes do little to address a major disincentive for people to save through tax-advantaged accounts—their complexity. While some provisions of the SECURE Act do simplify the law, many of the changes would create additional savings options and add administrative costs to savers.

Third, many of these new provisions mainly increase tax benefits that already inure to the benefit of higher income people. Low- and moderate-income people, for instance, often have little retirement saving, and, if they do, they generally can’t wait until age 72 to draw upon them. Michael Doran, in a June 10 Tax Notes article, lays this criticism on almost all recent pension tax legislation.

For decades, Congress has been unable to deal with the great inequality in retirement assets, tax subsidies for retirement, and, more generally, wealth. The result is that most households go into retirement with limited assets to support many years of old age while some households accumulate large amounts in a tax-favored fashion. I hate to criticize the SECURE Act. After all, it does represent modest progress, something sorely lacking on so many legislative fronts. But in the end, it is another missed opportunity.