How Government Tax And Transfer Policy Promotes Wealth Inequality

Posted: February 8, 2019 Filed under: Columns, Income and Wealth, Taxes and Budget Comments Off on How Government Tax And Transfer Policy Promotes Wealth InequalityFederal tax and spending policies are worsening the problem of economic inequality. But the tax breaks that overwhelmingly benefit the wealthy are only part of the challenge. The increasing diversion of government spending toward income supports and away from opportunity-building programs also is undermining social comity and, ironically, locking in wealth inequality.

Many flawed tax policies are rooted in the ability of affluent households to delay or even avoid tax on the returns from their wealth. By putting off the sale of assets, wealth holders can avoid tax on capital gains that are accrued but not realized. At death, deferred and unrecognized capital gains are exempted from income tax altogether because heirs reset the basis of the assets to their value on the date of death.

While individuals and corporations recognize taxable gains only when they sell assets, they may immediately deduct interest and other expenses. This tax arbitrage makes possible everything from tax shelters to the low taxation of the earnings of multinational companies.

Recent changes in the law have further eroded taxes on wealth. Once, the US taxed capital income at higher rates than labor income, today it does the reverse. For instance, the 2017 tax law sharply lowered the top corporate rate from 35 percent to 21 percent, but trimmed the top individual statutory rate on labor earnings only from 39.6 percent to 37 percent.

In theory, low- and middle-income taxpayers could use these wealth building tools as well. But the data suggest that the path to wealth accumulation eludes most of them, partly because they save only a small share of their income. Even those who do save $100,000 or $200,000 in home equity or in a retirement account earning, say, 5 percent per year may never reap more than $1,000 or so in tax savings annually.

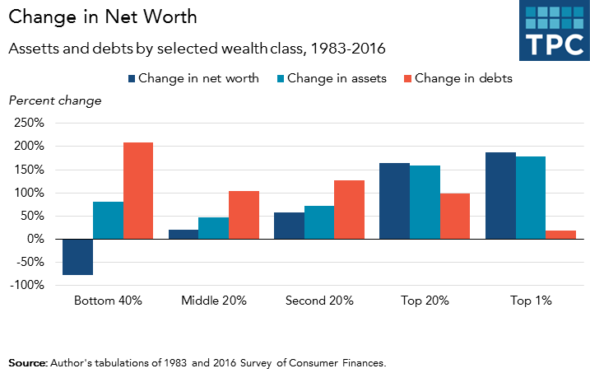

To understand what has been happening to the relative position of the non-wealthy, we need to dig a little into the numbers. Economics professor Edward Wolff of New York University discovered that in 2016 the poorest two-fifths of households had, on average, accumulated less than $3,000 and the middle fifth only $101,000. Trends in debt tell part of the story. From 1983 to 2016, debt grew faster than gross assets for most households–except for those near the top of the wealth pyramid.

It’s not that the government doesn’t aid those with less means. But almost government transfers support consumption, and only indirectly promote opportunity.

Consider the extent to which the largest of these programs, Social Security, has encouraged people to retire while they could still work.

Because of longer life expectancy and, until recently, earlier retirement, a typical American now lives in retirement for 13 more years than when Social Security first started paying benefits in 1940.That’s a lot fewer years of earning and saving, and a lot more years of receiving benefits and drawing down whatever personal wealth they hold.

Annual federal, state, and local government spending from all sources, including tax subsidies, now totals more than $60,000 per household—about $35,000 in direct support for individuals.Yet, increasingly, less and less of it comes in the form of investment or help when people are young. Thus, assuming modest growth in the economy and those supports over time, a typical child born today can expect to receive about $2 million in direct assistance from government. In the meantime, however, government has (a) scheduled smaller shares of national income to assist people when young and in prime ages for learning and developing their human capital, (b) reduced support for their higher education in ways that has now led to $1.4 trillion of student debt being borne by young adults without a corresponding increase in their earning power, and (c) offered little to bolster the productivity of workers.

Any number of programs could have a place in encouraging economic mobility, among them beefed-up access to job training and apprenticeships for non-college goers; wage subsidies that reward work; subsidies for first-time homebuyers in lieu of subsidies for borrowing; a mortgage policy aimed more at wealth building; and promotion of a few thousand dollars of liquid assets in lieu of high-cost borrowing as a source of emergency funds — you get the point. However, in one recent study, I found that federal initiatives to promote opportunity—many in the tax code—have never been a large fraction of government spending or tax programs and are scheduled to decline as a share of GDP.

It would be naïve to assume that fixing any of this will be easy. Republicans seem committed to reducing (not increasing) taxes on the wealthy, while Democrats reflexively support redistribution to those less well off, even when their proposals reduce incentives to save and work. But until we fix both sides of this equation, don’t expect government policy to succeed in distributing wealth more equally. After all, simply leveling wealth from the top still will leave the large number of households holding zero wealth with zero percent of all societal wealth.

This blog also appears on TaxVox. A longer version of this blog can be found in The Milken Institute Review, 21 (1): 16-27.

Challenges & Opportunities for Charities after the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act

Posted: May 21, 2018 Filed under: Nonprofits and Philanthropy, Taxes and Budget Comments Off on Challenges & Opportunities for Charities after the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs ActEugene Steuerle, Richard Fisher Chair at the Urban Institute and co-founder of the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center gave this presentation at the ABA Tax Meetings Exempt Organizations Committee luncheon in May 2018. A full transcript is available at taxpolicycenter.org.

“A pessimist sees the difficulty in every opportunity; an optimist sees the opportunity in every difficulty.”

I’d like to refine this idea, probably incorrectly attributed to Winston Churchill, with the wisdom of my teachers, by distinguishing among luck, serendipity, and misfortune. To me, luck—good or bad— results from random factors beyond our control. Serendipity reflects the good things more likely to happen when we put ourselves along a path with a higher-than-average probability of success, while misfortune happens, often unnecessarily, when we bet against a house that has stacked the odds in its favor.

I realize that the lexicographers may not fully agree with my definitions.

Chauncey M. Depew told the story that Noah’s wife one day was caught kissing the cook.

“‘Noah,’ she exclaimed, ‘I’m surprised!’

“‘Madam,’ he replied, ‘you have not studied carefully our glorious language. It is I who am surprised. You are astounded.’”

Are charities on a serendipitous path, where a virtuous cycle of improvement is more likely, or a path with greater odds of a vicious cycle of misfortune? I suggest that the treatment of charities in last year’s tax reform may reflect a path if not misfortunate at least less serendipitous than possible.

In any case, I want to spend most of this talk discussing why the current tax law is unsustainable and sets in motion forces for further reform. I then set out a bold but difficult agenda worth pursuing as we venture down that still-to-be-determined path.

READ MORE AT TAXPOLICYCENTER.ORG

How Late-in-Life Dads Like Donald Trump Are Eligible for a Social Security Bonus

Posted: April 9, 2018 Filed under: Aging, Taxes and Budget Comments Off on How Late-in-Life Dads Like Donald Trump Are Eligible for a Social Security Bonus

This article, coauthored with Allan Sloan, first appeared in ProPublica and The Washington Post.

Would you believe that President Donald Trump is eligible for an extra Social Security benefit of around $15,000 a year because of his 11-year-old son, Barron Trump? Well, you should believe it, because it’s true.

How can this be? Because under Social Security’s rules, anyone like Trump who is old enough to get retirement benefits and still has a child under 18 can get this supplement — without having paid an extra dime in Social Security taxes for it.

The White House declined to tell us whether Trump is taking Social Security benefits, which by our estimate would range from about $47,100 a year (including the Barron bucks) if he began taking them at age 66, to $58,300 if he began at 70, the age at which benefits reach their maximum.

Of course, if Trump, 71, had released his income tax returns the way his predecessors since Richard Nixon did, we would know if he’s taking Social Security and how much he’s getting. There’s no reason, however, to think that he isn’t taking the benefits to which he’s entitled.

Meanwhile, Trump’s new budget proposes to reduce items like food stamps and housing vouchers for low-income people. It doesn’t ask either the rich or the middle class to make sacrifices on the tax or spending side. And it doesn’t touch the extra Social Security benefit for which Trump and about 680,000 other people are eligible.

The average Social Security retiree receives about $16,900 in annual benefits. Does it strike you as bizarre that someone in Trump’s position gets a bonus benefit nearly equal to that?

Does it seem unfair that by contrast to Trump, most male workers — and for biological reasons, an even greater portion of female workers — can’t get child benefits because their kids are at least 18 and out of high school when the workers begin drawing Social Security retirement benefits in their 60s and 70s?

Trump is eligible for the Late-in-Life-Baby Bonus, as we’ve named it, because the people who designed Social Security decided in 1939, about five years into the program, that dependents and spouses needed extra support. They didn’t think much (if at all) about future expansion in the number of retirees, primarily male, who would have young kids.

The Late-in-Life-Baby Bonus goes to about 1.1 percent of Social Security retirees and costs about $5.5 billion a year. That’s a mere speck in Social Security’s $960 billion annual outlay.

Yet the Late-in-Life-Baby Bonus is a dramatic — and symbolic — example of hidden problems that plague Social Security, problems that few non-wonks recognize and that reform proposals have largely ignored.

Those problems are why the two of us — Allan Sloan, a journalist who has written about Social Security for years; and C. Eugene Steuerle, an economist who has written extensively about Social Security, co-founded the non-partisan Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center and is the author of “Dead Men Ruling: How to Restore Fiscal Freedom and Rescue Our Future” — combined forces to write this article.

We want to show you how we can help Social Security start heading in the right direction before its trust fund is tapped out, at which point a crisis atmosphere will prevail and rational conversation will disappear.

Calling for Social Security fixes isn’t new, of course, but the calls usually focus primarily on fixing the increasing gap between the taxes Social Security collects and the benefits it pays.

For us, however, the Late-in-Life-Baby Bonus is an example of why reform should not only restore fiscal balance but should also make the system more equitable and efficient, more geared to modern needs and conditions, and more attuned to how providing ever-more years of benefits to future retirees puts at risk government programs that help them and their children during their working years.

If all that mattered were numbers, we could easily provide better protections against poverty with no loss in benefits for today’s retirees, while providing higher average benefits for future retirees. But that works only if the political will is there to update Social Security’s operations and benefit structure. After all, a system designed in the 1930s isn’t necessarily what we’ll need in the 2030s.

And make no mistake about how important Social Security is. Millions of retirees depend heavily on it. According to a recent Census working paper, about half of Social Security retirees receive at least half their income from Social Security — and about 18 percent get at least 90 percent of their income from it. Add in Medicare benefits, and retirees’ reliance on programs funded by the Social Security tax are even higher.

Given the virtual elimination of pension benefits for new private-sector employees and the increasing erosion in pensions for new public-sector employees, Social Security will likely be needed even more in the future than it is today.

Simply throwing more money at Social Security isn’t the way to solve its imbalances, much less deal with the Late-in-Life-Baby Bonus and some of the other bizarre things we’ll show you.

Money-tossing would just continue the pattern of recent decades that provides an ever increasing proportion of national income and government revenue to us when we’re old (largely through Social Security and Medicare), and an ever smaller proportion when we’re younger (anything from educational assistance to transportation spending). This shortchanges the workers of today and tomorrow who will be called upon to fork over taxes to cover the costs of Social Security and other government programs for their elders.

We began with the Late-in-Life-Baby Bonus because giving people like Trump — a wealthy man with a young child from a third marriage — an extra benefit unavailable to 99 percent of retirees is a dramatic example of how problems embedded in Social Security cause inequities and problems that few people other than Social Security experts know about.

Think that we’re overreacting to a minor quirk? We aren’t. Here are some additional aspects of Social Security that we think violate standards of equal justice and common sense:

There’s the Single Parent Shortchange, whereby many single parents — largely mothers with below-average earnings — pay Social Security taxes to cover spousal and survivor benefits for other people even though the solo parents can’t receive them. Sure, many people contribute toward benefits they will never see, especially if they die before retirement age. But the Single Shortchange strikes us as horribly unfair. Single parents are among the lowest income payers of Social Security taxes. Why should they subsidize other folks’ never-working spouses in a way that gives the biggest benefits to the best-off people?

Then there’s the Agatha Christie Benefit: Some divorced people get a bonus from Social Security only if their former spouse dies. And the Serial Spouse Bonus: If someone has had, say, three spouses, each might get the same full spousal and survivor benefits available to the one lifetime spouse of another worker — provided that each marriage lasted at least 10 years. If a marriage lasts nine years and 364 days, the spouse gets zippo.

The Equal Earner Penalty means that a couple with two people each earning $40,000 gets about $100,000 less in lifetime benefits than a couple with one spouse earning $80,000 and the other earning nothing. This happens even though both couples and their employers pay identical Social Security taxes.

Many if not most of these inequities would be illegal in private retirement plans.

Fixing the Late-in-Life-Baby Bonus and the other inequities we mentioned (as well as plenty that we omitted) is more about remedying injustice than cutting costs; giving some people more benefits and others less would pretty much offset each other.

The system needs to be overhauled not simply to become more fair by giving less to the Trumps of the world and more to the less fortunate among us, but because Social Security, created in the 1930s, was largely constructed around a world in which married women were expected to stay at home. People also had shorter lifespans then and retired later, so that today retirees receive benefits for 12 more years on average than retirees in the system’s earlier days.

Back in 1965, there were about four workers for every person drawing benefits. Currently the ratio is in the low threes. Now, the decline in birth rates is hitting with a bang as baby boomers retire en masse, with the ratio expected to fall to about 2.2 in 2035. Each baby boomer retirement leads to an increase in takers and a decrease in makers.

Not dealing with this decline in workers-to-beneficiaries — a good chunk of which is caused by Social Security treating people as young as 62 as “old” — has broad implications for the revenues available for all government services, not just Social Security, as well as for the growth rate of our economy.

Even as fewer workers support more retirees, the average value of Social Security retirement benefits continues to rise. Look at the increasing “present value” of Social Security benefits for a two-income 65-year-old couple earning the average wage each year and expecting to live for an average lifespan.

In 1960, such a couple needed to have on hand $269,000 (in 2015 dollars) in an interest-bearing account to cover the cost of their lifetime benefits. Today, it’s about $625,000. In 2030, it will be about $731,000. And in 2055, when a Millennial age 30 this year turns 67, the full retirement age under current law, the present value of scheduled benefits hits seven digits: $1,029,000. Include Medicare, and benefits are about $1 million for today’s couple, rising to $2 million for the millennial couple.

These benefit-value increases are caused by a combination of longer lives for retirees and Social Security formulas that increase benefits as wages rise.

These numbers matter because Social Security isn’t like an Individual Retirement Account or a pension plan that sets money aside for you today for use when you retire. It’s mainly an intergenerational transfer system: Today’s workers pay Social Security taxes to cover their parents, who previously paid to cover their parents, who paid to cover their parents. That’s the way the system has worked since its founding in 1935. Social Security taxes paid by current workers and their employers get sent to beneficiaries, not stashed somewhere awaiting current workers reaching retirement age.

The system does have a trust fund that in the early 1980s was about to run out of money. A crisis loomed. As a result, after a report by the Greenspan Commission, Congress in 1983 enacted reforms that included gradually raising the normal retirement age (but not the early retirement age) and subjecting some Social Security retirement benefits to federal income tax.

This led to temporary surpluses while baby boomers were in their peak earning years. But now that boomers are retiring rapidly, Social Security’s tax revenues are falling farther and farther behind benefits being paid out.

The trust fund is projected to run dry in about 15 years. Meanwhile, every year without reform adds to the share of the burden required of the young, who already are scheduled to have lower returns on their Social Security contributions than older workers.

Do you think that if someone offered millennials a choice, they would want to face huge student debt, declining government investment in their children and higher future taxes (which are inevitable as deficits mount) — in exchange for a more generous retirement than today’s retirees get? Or would they prefer a system that treats them and their children better when they’re younger?

We’re both way past millennial age — but we know which we would prefer.

Now, we’ll show you how we can tweak Social Security to address the problems we’ve discussed without cutting benefits for current retirees or denying future retirees average benefits higher than current retirees get.

It’s about math. Social Security pays out far more than would be required to provide well-above-poverty-level benefits to all elderly recipients. Future growth in the economy will help tax revenues and benefits rise, which would give us room to modify the payout formulas and deal with problems that this iconic program isn’t addressing.

Those problems include poverty and near-poverty for millions of retirees, particularly the very old. That problem is greater for people who retired at 62 rather than waiting for their full retirement age, a move that locks them into lower payments for the rest of their lifetimes.

How can we orient the system more progressively to the needs of modern society, provide a stronger base of protection for all workers, and slow the growth rate of benefits to bring the system into better balance? To shore up Social Security permanently, it’ll be necessary to slow down the overall growth in benefits, encourage more years of work and end the pattern of people having ever-longer retirements as lifespans increase and Social Security doesn’t adapt its rules. At some point, it will also require a revenue (i.e., tax) increase, too.

Here, in simplified form, are some suggestions for making Social Security more modern and more fair.

- Change the benefit structure. Reduce the level of benefits that retirees get in their 60s and early 70s but give them higher-than-now benefits in their mid-to-late 70s and beyond. That would shift resources to retirees’ elder years when they have greater needs, including a higher probability of having to pay for long-term care.

- Raise the minimum benefit. Have a strong minimum benefit for most elderly that’s indexed to wage growth, which typically exceeds inflation. This would raise benefits for one-third to one-half of the elderly in a way that will essentially remove them from poverty.

- Trim benefit growth for those at the top. Offset at least part of the cost of higher minimum benefits by paying the highest-paid recipients less in the future than they would get under the current formula. Slow the rise in benefits for future retirees with way-above-average lifetime earnings by indexing their benefits to inflation rather than to wage growth.

- Index the retirement age. Having people work for additional years helps pay for higher levels of both lifetime and annual benefits. So if people on average are living a year longer, they should have to work a year longer. Those additional income and Social Security taxes would help support both Social Security and national needs that are higher priority than paying additional retirement years. Gradually phase out the early-retirement age that leads many healthy couples to retire on Social Security for close to three decades for the spouse who lives longer.

- Make spousal and survivor benefits more fair. Modify these benefits so that they provide higher benefits for those with greater needs rather than giving the richest bonuses to the richest spouses even when they contributed less in taxes than lower-income spouses. Otherwise, use rules similar to what private pensions use, so that benefits are shared fairly for the time of marriage together.

And one final thing: Bye-bye Late-in-Life-Baby Bonus. Stop paying retirees extra for children under 18. Continue the young-child bonus for widows or widowers below retirement age, and for people on disability.

Eliminating that bonanza for older parents would be a symbolic first step. And who can say? Perhaps now that lots more people (including possibly Trump himself) know that the Late-in-Life-Baby Bonus exists, our leaders might just be embarrassed enough to realize that the sooner Social Security is adapted to modern needs and circumstances, the better.

If this results in starting to fix Social Security the right way, the Late-in-Life-Baby Bonus will have delivered a big-time bonus of its own. The beneficiaries would be our future retirees, our workers and our country as a whole.

Why Tax Reform Flounders: The Case Of Doubling The Standard Deduction

Posted: November 2, 2017 Filed under: Taxes and Budget 3 Comments »This post originally appeared on TaxVox.

Do you want to know why tax reform is so hard? Consider one seemingly simple idea that has been floated by President Trump and congressional Republicans in their Unified Framework: roughly doubling the standard deduction. The closer you look at this proposal, the more you see how complicated it is.

Is doubling the standard deduction a good idea? Well, maybe. By granting more taxpayers a larger reduction in taxable income without making them itemize a list of specific deductible expenses, boosting the standard deduction can substantially simplify the tax filing process. It would also reduce taxes for some middle-income households. But…

It costs money. The Framework would partially offset the expense by eliminating the personal exemption. But…

Exchanging a larger standard deduction for repeal of the personal exemption raises the relative burden of taxes on households with children. But…

The Framework attempts to offset the elimination of personal exemption with a bigger child credit. That might help reduce some of the higher taxes caused by repealing the personal exemption. But…

These adjustments cost revenue and so would reduce the amount of rate reduction that Congress can pay for. And…

The share of households (including nonfilers) that itemize with the larger proposed standard deduction would be reduced, perhaps to as little as 5 percent, depending upon what happens to specific deductions. But…

If Congress reduces the number of itemizers, it would also reduce the number of people who’d take deductions for charitable giving, home mortgage interest, and state and local taxes paid. That, in turn, has charities, homebuilders, and state and local government officials worried. And…

Retaining tax incentives only for the highest income households makes zero sense for provisions meant to encourage families to own homes or give to charity. But…

Congress could create alternative subsidies for charitable donors, homebuilders, and state and local governments. But…

That could cost more foregone revenue and reduce the size of any tax rate reduction that could be paid for. And, whoops…

So far, we’ve pretty much forgotten about the poor and moderate-income taxpayers who would benefit little or not at all by an increase in the standard deduction. But…

To help them requires yet more money and reduces the amount of rate reduction that can be financed in a tax reform package. And, thus,

Each decision on each individual change not only causes new interactions affecting the amount of revenue other provisions in a bill would gain or lose, but…

It alters the distribution of winners and losers among individuals and industries that also must be addressed. And…

These are only some of the effects of one simple reform Now, think of what Congress and the President must tackle in a bill that revises the taxation of capital and labor, multinational corporations and partnerships, pensions and insurance. And…

You will get some inkling of why, as the president might say, “nobody knew” tax reform would be so hard.

Come The Flood, Who Should Pay To Help?

Posted: September 6, 2017 Filed under: Columns, Income and Wealth, Taxes and Budget 1 Comment »This post originally appeared on TaxVox.

Hurricane Harvey’s historic flooding has brought out the best in many people. They have put their lives in danger to save strangers, shared their food, and offered their homes. Citizens across the country are contributing to the United Way, Red Cross, community foundations, and churches. Race, creed, and social status seem to make little difference, and the political issues that divide us suddenly seem petty, almost separated from the real world in which we live, suffer, or thrive.

But because charities and individuals can do only so much, we have turned to government to act on our behalf. But even as we ask government to coordinate efforts and bear a large share of the cost of repair and rejuvenation, a question lingers: Who should pay for those costs? Or to ask another way, who should feel entitled to claim they are exempt from the social compact that says we should use our tax dollars to assist victims of an historic flood they could not predict or plan for? Once one broadens this question to include helping victims of poverty or poor health, or paying some share of the cost of our national defense, it lays bare the issue of who should pay taxes.

Join me, therefore, in speculating about who should be exempt from sharing in the tax burden for helping victims of Hurricane Harvey.

How about owners of capital? They claim they benefit society by building and holding onto wealth and promoting growth by investing that wealth. Though often exaggerated, their case has enough merit to support economic and legal arguments for converting the income tax to a tax on consumption. Indeed, our current tax system combines features of both and reflects the divisions over the role of savings and investment in enhancing our well-being.

Many owners of capital even claim they should pay “negative” tax rates, at least on returns from new investments through generous tax depreciation or expensing of debt-financed physical assets. Should the tax system exempt owners of capital who consume only modest portions of their income from helping to finance assistance for the victims of Harvey?

How about the poor? We exempt low-income households from income tax (though the poor often pay sales, excise, and payroll taxes), a choice that also has some merit. After all, how can one expect the poor to pay taxes when they can’t afford adequate food or housing? Of course, that issue is complicated because low-income people often receive more in government support than they pay in taxes.

How about the middle class? We’re running huge federal deficits today largely because no one wants to raise their taxes or cut their benefits. Democrats are willing to tax the rich and Republicans will take away benefits from the poor, but both parties appear to coddle the (very large) middle class. It is true that middle-income workers have seen little wage growth or upward mobility in recent years, but does that mean they should not do their part to help government cover the costs of floods or other public goods and services that otherwise would add to deficits?

How about the elderly? Yes, many are retired and on fixed incomes. But many are reasonably well off and enjoy a permanent tax exemption on income from sources such as Roth retirement accounts. Can we as a nation go back on that deal? How about those who die with large estates? They could have realized income by selling assets and consumed that wealth when alive. But if they did not, should they be subject to an estate tax upon death? How about companies that get special business tax breaks? Don’t they need tax help to ensure their competitiveness with firms in other countries?

And, finally, how about you and me? Why should we have to pay taxes when it appears almost nobody else does? But then there are those people suffering in the wake of Hurricane Harvey.

Tax Reform: Start with the Fundamentals

Posted: August 22, 2017 Filed under: Taxes and Budget 2 Comments »This post originally appeared on TaxVox.

For the umpteenth time, Congress and the Trump Administration are going back to the tax reform drawing board, just as they have had to do for health reform. These policymakers could help themselves by recognizing that you can’t go back to a place you’ve never been.

Many policymakers look to the Tax Reform Act of 1986 as a model for successful reform, but largely ignore its lessons. Here is one of the most important: the success of the ’86 act was built on a solid core—a set of fundamental principles accepted by conservatives and liberals alike. They included equal justice for those in equal circumstances, simplicity, and–to a large extent–efficiency.

Agreeing on that core made it possible for reformers of all stripes to first address issues of common concern before turning to more conflict-laden issues, such as the taxation of capital income. While the political process of passing the ’86 act bent those principles, it never broke them. And the result was the only comprehensive revenue-neutral reform in the hundred-year history of the income tax.

Don’t get me wrong, 2017 is not a replay of 1986. Heraclitus was right: you can’t step into the same stream twice. But you can learn from previous crossings.

To start, it’s a myth that there was more friendly cooperation in the mid-1980s. Indeed, political war raged both within and between political parties.

Democrats were smarting over their electoral losses while Republicans fought over whether President Reagan was “being Reagan” whenever he did something one faction disliked.

Within the Treasury Department, extreme supply-siders who held that tax cuts paid for themselves fought with those who favored cleaning up the tax code rather than simply giving away money through tax cuts. Even some reformers questioned whether they should spend time on a tax reform study commissioned by President Reagan, which was largely viewed as an attempt to avoid debating tax issues during the 1984 presidential campaign.

In early 1984 when I became the economic coordinator of Treasury’s tax reform study, people in the Office of Tax Analysis were struggling over how to start. Should we focus on consumption taxes or income taxes? Should the Administration consider an add-on value added tax to finance a smaller income tax? Should we aim for a modest bill or the more comprehensive plan the Administration eventually championed? Should we expand tax breaks for business investment or pare them down to finance lower rates?

Sound familiar?

As an initial step, I encouraged Treasury staff to divide the overall reform effort into about twenty modules, each covering dozens of specific tax code provisions. Almost everything was on the table: pensions; housing; health; treatment of marriage, children, and the elderly; tax shelters; capital gains; depreciation; and international taxation, to mention only a few. We prepared briefs for Treasury Secretary Donald Regan on how to reform each area, and asked him to keep an open mind about politically difficult choices at this early stage and leave compromises of the principled tax reform options to later political bargaining.

To establish a solid core of reforms, we first dealt with items that would be common among an ideal income or consumption tax, except for taxation of capital income. While we aimed for roughly the same level of progressivity for the overall tax system as the then-current tax code, we did not focus on the progressivity of each particular provision. We recommended killing an inefficient subsidy favoring low- or middle-income taxpayers since on average we could hold those households harmless by reducing their tax rates.

Today’s reformers would benefit by creating a similar core on which to build reform. For example, defenders of the status quo would have a harder time making their case if reformers can show that a new tax system would increase charitable giving, support home ownership, make education more accessible, or protect retirees without losing as much tax revenue as the current system.

Similarly, they could simplify multiple higher education subsidies, capital gains taxation, and various definitions of a “child.” They could reduce penalties on marriage and on some families with children. And they could curb tax-driven investments without constraining economic decisions.

Contrast this approach with the flailing so far, where elected officials began by proclaiming support for cutting taxes on corporations and then, by extension, partnerships and the middle class. At best that’s like announcing a low purchase price for both new luxury and middle-income condos before ever designing the building housing them. Lawmakers would have much more success by first carefully creating a solid foundation for tax reform and then building out the new reforms.

Tax Reform Isn’t Just About Revenue but Health Insurance, Housing, and More

Posted: July 21, 2017 Filed under: Columns, Health and Health Policy, Taxes and Budget 1 Comment »This post originally appeared on TaxVox.

Taxes aren’t just about raising money for government. Policymakers engaging in tax reform must recognize how their decisions can disrupt markets for a wide range of economic activity, including healthcare, housing, and charitable giving. Some of those behavioral reactions may be secondary and unintended, but they can’t be ignored.

The Tax Policy Center has described some of the potential impacts of President Trump’s tax ideas on charitable giving and in the way businesses organize themselves. But it’s worth looking at two other examples—health insurance and homeownership—to see how tax changes can affect economic behavior. In both examples, tax reform can improve efficiency and equity, but only if it is well designed.

Employer-provided Health Insurance.

In a recent press conference, Treasury Secretary Steven Mnunchin and Director of the National Economic Council Gary Cohn implied that Trump’s tax plan could limit existing tax breaks for employer-sponsored health insurance (ESI). It would be one of a long list of tax preferences that Administration may target.

But any significant cut in subsidies for ESI could lead employers to reduce or even eliminate health insurance as part of employee compensation. The effects of such a decision could be substantial and most likely change the way people get health insurance. Tax reform must be designed with regard to its effects on subsidies offered through the Affordable Care Act or the House’s recently passed replacement.

For many years, health policy experts have suggested replacing the ESI exclusion with a tax credit. But the ACA and the House bill, and their related costs, largely depend upon retaining the ESI exclusion while adding subsides for those who buy outside the employer market.

The ACA’s exchange subsidy is larger for many employees than the value of their exclusion. Thus, employers already have some incentive to drop ESI coverage, send employees to an exchange, and share the net savings. Yet, so far, few have done so in part due to uncertainty about the future of the ACA and the reluctance of managers to give up their existing coverage. It is not clear how employers would respond to tax reform under the ACA or the House’s credits, which are less generous but in some cases more flexible.

Tax Subsidies for Housing

Although Cohn insists that “homeownership would be protected” under Trump’s tax plan, the Administration is considering several proposals that would significantly reduce incentives to buy housing.

Here are just three examples: Lowering tax rates would make the mortgage interest deduction less valuable. Eliminating property tax deductions as part of a repeal of the state and local tax deduction could raise taxes for homeowners who itemize. And doubling the standard deduction would significantly reduce the number of taxpayers taking deductions for mortgage interest.

In this new world, renters would increase in numbers and the number of homeowners would decline.

Like the exclusion for employer-provided health insurance, the tax subsidies for homeownership are both inefficient and inequitable. They provide an incentive mainly to those who need it least because the benefits are concentrated among those with higher incomes.

While it might make sense as a matter of tax policy to give middle-income individuals a higher standard deduction in lieu of the opportunity to itemize expenses, does it make sense as a matter of housing policy to leave a mortgage interest deduction concentrated on a select few taxpayers, largely with incomes well above average? And to what extent should equity owners, who still maintain an incentive to own homes, as opposed to taking out their equity and putting it into a saving account, be favored relative to borrowers? After all, younger and wealth-constrained, households are the ones most in need of borrowed funds to own their first homes, and they already have a far smaller share of total societal wealth than they did a generation ago

Providing some alternative incentive, such as to new homeowners, might help address some of these housing policy issues.

My concerns are not intended to throw cold water on tax reform. But they are a warning about the importance of doing it right.

Tax subsidies for health insurance and homeownership do need reform, but policymakers must ask themselves whether their new tax system creates the right set of incentives for the right people and integrates well with spending programs aimed at the some of the same objectives. They must also be sure to adjust as necessary to avoid undesirable behavioral responses. If they don’t, they may weaken or even destroy the benefits of reform.

A Debt Straightjacket or a Misdiagnosed Disease?

Posted: July 7, 2017 Filed under: Economic Growth and Productivity, Taxes and Budget 1 Comment »Noting rising public and private debt across the developed world, International Economy magazine recently asked a group of economists, including me, “Has the world been fitted with a debt straightjacket?” Below is the response I gave. You can see the full range of responses given by others here (PDF).

—

A straightjacket, yes, but debt defines its features poorly. Debt is merely one symptom of a disease that has vastly restricted the ability of developed nations to respond to new needs, emergencies, opportunities, and voter interests. The disease: the extraordinary degree to which past policymakers have attempted to control the future—building automatic growth or growing public expectations into existing spending and tax subsidy programs while refusing to collect the corresponding revenues required to pay for them.

In Dead Men Ruling I show how this leads to a “decline in fiscal democracy”—the sense by officials and voters alike that they have lost control over their fiscal destiny. Though the degree and nature of the problem varies by type of government and culture, research so far in the U.S. and Germany, two countries with greater fiscal space than most other developed countries, confirms this historic shift.

We must understand how we got here if we ever expect to get a cure, since defining the problem by the debt symptom has led mainly to periodic deficit cutting that leaves the same long-term bind, frustrating voters and officials alike while increasing the appeal of anarchists and populists.

For most of history, nations with even modest economic growth wore no long-term fiscal straightjacket. Even with the debt levels left at the end of World War II, economic growth led to rising revenues, while most spending grew only through newly legislated programs or features added to programs. Typically existing programs were expected to decline in cost, e.g., as a defense need was met or construction was completed. Until recent decades budget offices did no long-term projection, but if they had, they would have revealed massive future surpluses over time even when a current year revealed an excessive deficit. Year-after-year profligacy was still a danger, but it wasn’t built into what in the U.S. is referred to as “current law.”

Today, rising spending expectations are built into the law through features such as retirement benefits that rise with wages, expectations that health care spending will automatically pay for new innovations, and failure to adjust for declining birth rates and the corresponding hit on spending, employment and revenues. At the same time, officials fail to raise the revenues required to meet, much less fund, those laws or voter expectations.

A rising debt level relative to GDP is merely one symptom. Reduced ability to respond to the next recession or emergency is another, while the increasing share of government spending on consumption and interest crimps programs oriented toward work, investment, saving, human capital formation, and mobility.

Politically the chief budget job of elected officials turns from give-aways to avoid growing surpluses to take-aways that renege on what the public believes is promised to them. Economic populists, fiscal hawks and doves alike, don’t help when their fights over short-run austerity ignore the fundamental long-term disease.

The bottom line: flexibility, not merely sustainable debt, is required for any institution—business, household, or government—to thrive.