A Debt Straightjacket or a Misdiagnosed Disease?

Posted: July 7, 2017 Filed under: Economic Growth and Productivity, Taxes and Budget 1 Comment »Noting rising public and private debt across the developed world, International Economy magazine recently asked a group of economists, including me, “Has the world been fitted with a debt straightjacket?” Below is the response I gave. You can see the full range of responses given by others here (PDF).

—

A straightjacket, yes, but debt defines its features poorly. Debt is merely one symptom of a disease that has vastly restricted the ability of developed nations to respond to new needs, emergencies, opportunities, and voter interests. The disease: the extraordinary degree to which past policymakers have attempted to control the future—building automatic growth or growing public expectations into existing spending and tax subsidy programs while refusing to collect the corresponding revenues required to pay for them.

In Dead Men Ruling I show how this leads to a “decline in fiscal democracy”—the sense by officials and voters alike that they have lost control over their fiscal destiny. Though the degree and nature of the problem varies by type of government and culture, research so far in the U.S. and Germany, two countries with greater fiscal space than most other developed countries, confirms this historic shift.

We must understand how we got here if we ever expect to get a cure, since defining the problem by the debt symptom has led mainly to periodic deficit cutting that leaves the same long-term bind, frustrating voters and officials alike while increasing the appeal of anarchists and populists.

For most of history, nations with even modest economic growth wore no long-term fiscal straightjacket. Even with the debt levels left at the end of World War II, economic growth led to rising revenues, while most spending grew only through newly legislated programs or features added to programs. Typically existing programs were expected to decline in cost, e.g., as a defense need was met or construction was completed. Until recent decades budget offices did no long-term projection, but if they had, they would have revealed massive future surpluses over time even when a current year revealed an excessive deficit. Year-after-year profligacy was still a danger, but it wasn’t built into what in the U.S. is referred to as “current law.”

Today, rising spending expectations are built into the law through features such as retirement benefits that rise with wages, expectations that health care spending will automatically pay for new innovations, and failure to adjust for declining birth rates and the corresponding hit on spending, employment and revenues. At the same time, officials fail to raise the revenues required to meet, much less fund, those laws or voter expectations.

A rising debt level relative to GDP is merely one symptom. Reduced ability to respond to the next recession or emergency is another, while the increasing share of government spending on consumption and interest crimps programs oriented toward work, investment, saving, human capital formation, and mobility.

Politically the chief budget job of elected officials turns from give-aways to avoid growing surpluses to take-aways that renege on what the public believes is promised to them. Economic populists, fiscal hawks and doves alike, don’t help when their fights over short-run austerity ignore the fundamental long-term disease.

The bottom line: flexibility, not merely sustainable debt, is required for any institution—business, household, or government—to thrive.

The California Secure Choice Retirement Savings Program: Why pension reform turns inefficiently to the states

Posted: December 5, 2016 Filed under: Economic Growth and Productivity, Taxes and Budget 2 Comments »This post originally appeared on TaxVox.

By: C. Eugene Steuerle and Pamela Perun

Starting as soon as it can be made operational, perhaps in 2018, as many as 7 million private-sector California workers who currently have no access to a job-based retirement plan will be automatically enrolled in a state-managed savings program. The California Secure Choice Retirement Savings program will start with employee contributions of 3 percent of earnings, though the state board managing the initiative could increase the contribution rate to as much as 8 percent. While workers will be auto-enrolled, they can opt out of the plan.

The new law is an important step toward securing better retirement coverage for those who require it most. Too many people reach old age with far too little saving to meet their long-term needs.

While an interesting idea ,the plan, however, faces limits that would be better served through federal reform. For instance, companies that operate across state borders don’t want to be bogged down with 50 different sets of state regulations. In addition, federal law currently grants employee deposits fewer tax breaks than are enjoyed by employer contributions. Only federal law changes can deal with those challenges.

However, changes to federal law that reduce tax revenues may be blocked by the constraints of the federal budget process.

Here’s the rub. At the federal level, any pension reform that might succeed in securing significantly more retirement saving will be scored as losing revenue to the federal government. Big revenues. And no major tax reform or tax cut in recent years, as well as President-elect Donald Trump’s campaign tax plan, has made pension reform a priority.

Suppose, for instance, that a national reform increases net contributions to traditional retirement plans by $80 billion, or one percent of the $8 trillion of wages and salaries that workers earned in 2016. If those savers reduce their tax on new deposits by 15 percent, revenues would decline by $12 billion in the first year and by more than $100 billion over a decade, even after accounting for taxable withdrawals.

Even if we see big new tax cuts in a Donald Trump presidency, that’s a lot of money. However, state legislators do not face the same budget process constraints as federal lawmakers. They are indifferent to the effects of state law on federal revenues, and the impact of a big tax-advantaged savings plan on state revenues are relatively modest given lower state income tax rates. Hence, for now, all incentives point toward the states acting independently, inconsistently, and inefficiently in tackling our nation’s larger retirement security problems.

There are alternatives. We have proposed an alternative strategy through a federal plan that would greatly simplify current law while broadly encouraging both employer and employee contributions.

Of course, it makes some sense to let states operate as laboratories of democracy. However, the more successful this California effort and similar ones being considered in Illinois, Oregon, and Connecticut, the greater the need for the type of coordination that only the federal government can provide. Until we get our federal budget into some sort of order, however, federal reform likely will continue to be stifled. Catch 22, once again.

Photo courtesy of Randy Bayne/via Flickr Creative Commons.

Social Security must be fair for everyone, not just retirees

Posted: October 11, 2016 Filed under: Aging, Economic Growth and Productivity 6 Comments »A version of this post originally appeared on The Washington Post.

+What should the next president do to make Social Security more sustainable?

No one should assess Social Security policy in isolation. What is fair in Social Security must relate to what is fair for the national budget as a whole.

Congressional Budget Office projections indicate that by 2026 we’ll be 21 percent richer, and that tax revenues will rise at a slightly higher rate. That means we stand before an ocean of opportunity. But of the expected $850 billion in additional real revenues, about 150 percent (or about $1.3 trillion) is committed entirely to increasingly expensive payments to Social Security, health care and interest on the debt. And as a result of these commitments, almost anything that represents investment — in our children, infrastructure or the basic functions of government — takes it on the chin.

[The problem with Social Security lies in its history]

Even as revenues grow, the number of workers available to pay for Social Security benefits is falling rapidly, meaning that either benefits must be cut, taxes increased, or both. Every delay puts more of the cost on the young.

Social Security maintains a design built around an economy and family structure of the past. People aged 65 now live about six years longer and retire even earlier than they did in 1940 when the system first paid benefits. That means families like Clinton’s, Trump’s and mine will be getting hundreds of thousands of dollars more in lifetime benefits than they would have when the system was first created, while many future elderly will still be left in poverty.

So what must be done? Slow down and reorient the growth in benefits scheduled for future retirees. A typical couple retiring today gets more than $1 million in lifetime Social Security and Medicare benefits; millennials are unrealistically scheduled to get $2 million. That growth can be slowed without being stopped and shifted more toward those who are truly old with low- to moderate-incomes. While Social Security’s long-recognized shortfalls inevitably mean someone must pay, those with above-median incomes are the ones with the money.

Still, no Social Security benefits need to be cut for those currently retired. To do better for those elderly with median or lower lifetime incomes, we should raise minimum benefits and give credit for raising children. We should also fix absurd rules around spousal and survivor benefits and other sources of inequity.

[Social Security needs to return to its anti-poverty roots]

The current system discourages work in late-middle age, something that is no longer easily affordable and which reduces economic growth, personal income and tax revenues. Congress should reduce Social Security’s natural disincentives for work both by adjusting the retirement age as we live longer and saving a larger share of lifetime benefits for later ages, when health needs rise and work is less possible. As lifespan increases, Social Security now promises a typical newly retired couple aged 62 an average of more than 28 years of benefits (today, one of them is likely to make it to 90 years of age). That’s more than enough; there are greater societal needs than the desire for more retirement years.

Finally, the tax issue. While some broadening of the Social Security tax base is possible, government needs to concentrate on raising revenue for high priorities apart from Social Security: our growing national debt, and vital investments such as education, infrastructure and support for working families. Campaigns are about giveaways, but true reform requires looking at what must be done and how, whether we want to or not.

Photo courtesy of The Social Security Administration, Public Domain.

STUDENT DEBT: THE MACRO QUESTION

Posted: October 5, 2016 Filed under: Economic Growth and Productivity 5 Comments »The 2016 presidential election has made student debt a national issue. Two just-released books, one by Sandy Baum and one by Beth Akers and Matt Chingos, have done a great job of identifying the real problems with student debt, while debunking much of the rhetoric that tends to identify wrong problems and come up with wrong solutions. I highly recommend the books, though I am hardly unbiased since Matt and Sandy are colleagues of mine.

By focusing on the real risks associated with the current system, the authors emphasize that we must pay attention to who acquires the debt and who benefits from it. For instance, future doctors and lawyers with high returns to postgraduate education acquire some of the highest levels of student debt. Akers and Chingos emphasize that over 40 percent of student debt is held by those in the top 20 percent of the income stratum. Thus, simply eliminating student debt would help the highest income borrowers most.

Sandy Baum focuses on designing proposals that would prevent so many at-risk students from borrowing for programs unlikely to serve them well. She especially discredits proposals that provide the most assistance to those who are actually in the best position to repay their loans. One example of how all this plays out was shown earlier by some other colleagues: blacks as a group, who are less likely to come out of college with a degree, end up with higher average student debt than whites.

Here I wish to address a more macro question: whether this shift toward higher student debt represents just one more way that government has disinvested in the economy. As students accumulated $1.3 trillion in debt, did government make an equivalent increase in investment in what economists often call “human capital”? Or did government simply shift additional burdens onto these students with few or no significant gains in educational achievement nationwide? Or something in between?

When we look at budgets as a whole, both federal and state, it’s quite clear how resources are being shifted. Average tax rates are about where they have been, maybe a touch higher. Taxpayers may have gotten a break for a while as rates went down a bit and then back up a bit, but that’s not the main story. Both federal and state budgets have adopted huge spending increases for retirement and health care. States have also put a lot more into prisons, while the feds have put much more toward interest costs, though offered a reprieve—if one can call it that—by a weak worldwide economy that has led to low interest rates.

Clearly, a smaller share of revenues and incomes goes for education—not just higher education, but primary and secondary education as well. Almost anything that might qualify as investment, such as infrastructure, has also seen a downturn.

Taking the budget as a whole, therefore, it’s hard to avoid the conclusion that the net effect of federal and state policies, of which student loans become merely one example, has been a disinvestment in the economy as a whole.

This raises an additional issue for those assessing programs by comparing benefits to costs. In the case of student loans, if more borrowing on average increases human capital by more than the value of the loans, we would say it was worthwhile for individuals to take out those loans. Correspondingly, if we were replacing a system with less education and no loans with one that on net created more assets than debt, we would likely conclude that the shift was worthwhile societally, not just individually. However, starting from a society that had financed education more directly, the student loan policy may be a failure.

Put another way, the starting point matters. In this arena and others we usually want government to increase net investment, as well as improving the allocation of funds so as to garner the highest returns on the investment, and we need to figure out the effect across the entire balance sheet of assets and liabilities. The individual perspective compares the personal increase in assets with the personal increase in borrowing and asks whether enough people come out ahead that society is better off. But if the additional loans don’t finance an increase in education societally, whether because some students don’t attain degrees or others don’t acquire any more education than they would have undertaken anyway, then we must ask what we got for our money.

If this debt policy additionally discourages risk taking and marriage after education, then all this debt may even reduce investment over time in education, businesses, and homes combined. Unfortunately, I think this has been the most likely outcome of recent policy. Even the creative reforms that Baum, Akers, and Chingos recommend won’t restore those past losses, though they may help minimize them in the future.

Whatever your take on this issue, this presidential campaign makes clear that higher education reform very likely will be on the national agenda in the next year or two. The Baum and Akers-Chingos studies should be required reading for anyone undertaking that reform.

Photo courtesy of Andrew Bossi-Flickr.

Reducing Wealth Inequality Requires Holding Risky Assets

Posted: September 29, 2016 Filed under: Economic Growth and Productivity, Income and Wealth 5 Comments »How do people build wealth? How do low-wealth families climb the economic ladder? It’s simple. They save. They get decent or even above-average returns on their savings. And they reinvest those returns over time. Unless policymakers and advocates face up to these simple propositions, policy efforts to reduce wealth inequality will go for naught.

Over many years I have had the privilege of working with groups concerned with wealth inequality and promoting asset growth. One of them, the Corporation for Enterprise Development, has been holding its biennial Assets Learning Conference, engaging over one thousand professionals. I cofounded and work with the Urban Institute’s Opportunity and Ownership initiative, which researches wealth inequality. Because of their concern for the well-being of low-income, low-wealth households, these engaged individuals often try to figure out ways that government can simultaneously support and protect more vulnerable populations. One consequence, though, is a hope and sometimes belief that asset-building policies can increase wealth without reducing consumption and can generate higher returns without requiring risk taking.

But saving by definition means forgoing consumption. Even if government provides the money, it forces individuals to save rather than immediately spend that money.

This fact creates a controversy among progressive advocates. A dollar spent on wealth building means a dollar not spent on food, health care, or other transfers for immediate needs.

Finance 101 further teaches that higher returns on saving come from investment in riskier assets. The expected return on stock is higher than the return on bonds, and the expected return on bonds is higher than the return on savings accounts and Treasury bills. Over several decades the after-inflation investment return on corporate stock has averaged close to 6 percent, whereas the return on five-year government bonds sits at around 2 percent. The expected return on many saving and checking accounts is close to zero. Compounded over time, average stock market investors will see their money multiply about eight times after 36 years; average medium-term bond investors will see theirs double. Savers using only checking and saving accounts, meanwhile, will see little if any growth.

Over short periods, however, stocks have the highest risk of the assets just mentioned, while savings accounts have the least. Over very long periods, the risks reverse. Investing in the stock market is like flipping a coin bent enough that betting on heads on average nets a good return, but there’s a high probability of a loss with a few flips. As the number of flips increase, the odds of having more heads than tails get better and better. John Bogle, founder of Vanguard, said it like this: “The data make clear that, if risk is the chance of failing to earn a real return over the long term, bonds have carried a higher risk than stock.”

It’s possible to buy stock and insure against losses relative to, say, a short-term bond. But the insurance will cost the difference in returns plus additional transactions costs. Thus, attempts to provide low- and moderate-wealth households both higher returns and low risk tend to fail.

Just look at the household assets reported on wealth surveys. Wealthy households hold the vast majority of their wealth in stock and small business assets and real estate either directly or through retirement accounts. They make much of their money not just by saving more initially, but by allowing the saving on higher-return assets to compound. Low-wealth households, meanwhile, own few or no high-return assets, tend to hold more debt relative to their incomes, and often pay higher interest on that debt.

Timing matters, too, especially when it comes to large, infrequent purchases like buying a home. Mortgages became widely available to lower-income households in the early 2000s, when home prices were at a peak, but less available after the Great Recession, when prices were lower and owners were getting capital gains in many regions. As Bob Lerman, Sisi Zhang, and I have pointed out, this created a “buy-high, sell-low” mortgage policy that devastates low-wealth households, including the young.

The policy implications are clear. Simply taxing the rich more or distributing more to low-wealth households will do little to narrow wealth inequality. Transfer programs rarely encourage wealth-holding and may even exacerbate private wealth inequality by imposing asset tests and by favoring renting over homeownership.

None of this means that the rich shouldn’t pay higher taxes or that transfer programs don’t protect vulnerable families or even provide a type of “asset” in the form of income and risk protection. That’s another subject. The subject here is the distribution of private wealth and the power it brings.

Advocates and lawmakers trying to counter wealth inequality, therefore, must find ways to get low-wealth savers into longer-term assets like stock and real estate, mainly through retirement plans and homeownership. Small business ownership also matters. And, subsidies provided by government must encourage long holding periods—that is, saving over time, not short-term deposits. Deposits followed quickly by withdrawals or loans don’t increase saving. Nor do proposals that subsidize borrowing encourage homeownership, since, by encouraging more borrowing, they often reduce net home equity.

Of course, many low-wealth households are not ideal investors in riskier assets. But there are risks and there are risks. Remember that Social Security and Medicare—and, to some extent, traditional pension plans—already require nonelderly adults, whatever their other needs, to “save” some income today to prevent inadequate income in old age.

Successful investment requires forgoing consumption, taking risks, and adopting a long-term view. Those attempting to address wealth inequality must either recognize these fundamental facts—and the related costs involved—or fail in their mission.

Photo by 401(K) 2012 via Flickr Creative Commons.

Restoring More Discretion to the Federal Budget

Posted: September 15, 2016 Filed under: Aging, Economic Growth and Productivity, Taxes and Budget 1 Comment »By: C. Eugene Steuerle and Rudolph G. Penner

The nation must change how it makes budget decisions. Permanent entitlement and tax subsidy programs, particularly those that grow automatically, dominate federal spending. Their growth, often set in motion by lawmakers long since dead or retired, is not scrutinized with the same attention as the discretionary programs Congress must vote on each year to be maintained, as well as grow. The result? A predetermined, inflexible federal budget that does not reflect our country’s needs.

Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid, the three largest entitlement programs, accounted for $1.9 trillion, or about half, of federal spending in 2015. More important, they will absorb more than all the increase in tax revenues our growing economy will provide over the next decade and beyond. This astounding growth, combined with political unwillingness to collect enough taxes to pay for current government spending, translates to accelerating increases in budget deficits and national debt.

Congress can take steps to draw more attention to long-term sustainability when making budget choices. One possible reason such growth remains unchecked is that much of the budget process currently focuses at most on total spending and revenues over the next 10 years. This leads to game-playing when policymakers decide to increase government largess: Costs can be hidden outside the budget window, or costly “pay-fors” can be postponed for a later Congress to deal with.

Reforms focused on a 10-year window are similarly myopic and inadequate. To protect existing beneficiaries when enacting reform, typically only a small portion of the deficit reduction shows up in the first decade; the most impact is made on future beneficiaries, not current ones. A longer time horizon also makes reforms more palatable politically; it shifts the focus from threatening today’s retirees to allowing younger households to garner greater resources during their working years in exchange for less relative growth in government retirement benefits.

Better presentations of the budget priorities set by the president and Congress is crucial for reform. Current budget documents do not give a very clear picture of how much growth in spending is predetermined versus newly legislated. Nor do they reflect the relationship among real growth in taxes, tax subsidies, and spending programs.

What would such an improved portrayal show? Near-term problems in how our money is spent, not just long-term ones related to growing debt. Today’s current law, as estimated by the Congressional Budget Office, implies $1.281 trillion more inflation-adjusted dollars will be spent in 2026 than in 2016: $845 billion from revenue increases and $436 billion from deficit increases. Of these dollars, 33 percent will be devoted to Social Security and 37 percent to health programs, mostly Medicare and Medicaid. A further 27 percent will be devoted to larger interest costs related to debt increases.

What does this leave for everything else? Essentially nothing. About 1 percent of the $1.281 trillion would be spent for defense and 4 percent for other mandatory spending, most of which is for non-health entitlements. Domestic programs that must be funded every year will be cut slightly in real dollars while declining substantially as a share of national income. Only much larger deficits at an unsustainable level prevent further hits on these programs.

Entitlements should be reviewed more frequently, and periodic votes of Congress should determine most of their growth. Permanent tax subsidies need similar scrutiny and limits placed on their automatic growth. In good times, tax rates must be high enough to avoid pushing today’s costs onto tomorrow.

Automatic triggers that activate if economic and demographic developments turn out worse than expected are one way to slow benefit growth or increase revenues. Sweden, Canada, Japan, and Germany use triggers in their Social Security programs; U.S. policymakers can learn from them. Of course, triggers work best when they reinforce sustainable programs. If required adjustments are too politically painful, Congress will simply override them, as it did for many years with updates to physician payment rates in Medicare.

We must grant future voters and those they elect more flexibility to allocate budget resources. Improving the way Congress budgets can enable government to better respond to changing needs, set new national priorities, and get off a disastrous fiscal path.

— C. Eugene Steuerle is an Institute fellow and the Richard B. Fisher chair at the Urban Institute. Rudolph G. Penner is an Institute fellow at the Urban Institute. They are the coauthors of “Options to Restore More Discretion to the Federal Budget,” a joint publication by the Mercatus Center at George Mason University and the Urban Institute.

A version of this post originally appeared on Economics21.

Photo by 401(K) 2012 via Flickr Creative Commons.

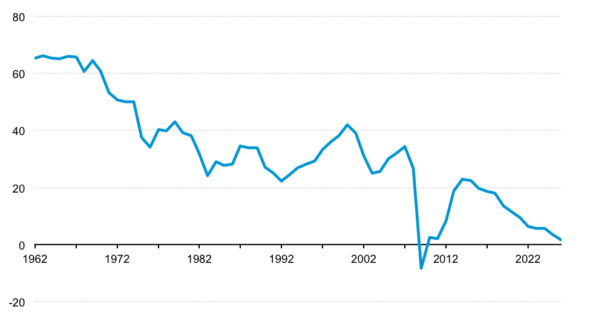

The Federal Government on Autopilot: Mandatory Spending and the Entitlement Crisis

Posted: July 8, 2016 Filed under: Economic Growth and Productivity 1 Comment »Yesterday, I testified before a House Judiciary Committee Task Force on the risks of having so much of government on auto-pilot. Through permanent, automatic, and growing mandatory programs and tax subsidies, past lawmakers have pre-committed the majority of new revenues that the government is scheduled to collect. As a result, today’s lawmakers have little ability to revise priorities to keep up with a rapidly changing world. Here is a lightly edited version of my oral testimony. My full written testimony is here.

Let me begin by noting that we live at a time of extraordinary possibility, but you wouldn’t believe it by looking at the headlines. We have never before been so rich, even if many needs remain unaddressed, and many do not share in that growth.

Yet, partly because we are ruled over by dead men (and, yes, they were largely men), we stand with our backs to an ocean of possibilities that lay at our feet. I try to show this by two means. First, a decline in what I call fiscal democracy—the discretion left to current voters and policymakers to determine how government should evolve. This index measures how much of our current revenues are pre-committed to programs that require no vote by Congress or, in technical terms, to mandatory spending programs. This index is politically neutral: fiscal democracy is reduced through both increases in mandatory spending and reductions in taxes.

By this measure, in 2009 for the first time in US history, every dollar of revenue was pre-committed before the new Congress walked through the doors of the Capitol.

Steuerle-Roeper Index of Fiscal Democracy

Percentage of federal receipts remaining after mandatory and interest spending

Source: C. Eugene Steuerle and Caleb Quakenbush, 2016 calculations based on data from OMB FY2017 Historical Tables and CBO Updated Budget Projections: 2016 to 2026.

Notes: Projections assume current law.

The second piece of evidence comes from simply comparing two budgets: first, a traditional budget such as prevailed over most of this nation’s history, where spending is largely discretionary, and, second, a modern budget, where growth in spending and tax subsidies are committed to rise automatically faster than revenues. Congress and the president end up in a never-ending game of Whack-A-Mole or, should I say, Whack-Some-Dough. No wonder there are still budget problems after deficit-reducing actions in 1982, 1983, 1984, 1987, 1990, 1993, 1997, 2005, 2011, 2013, and 2015, among others.

[The Need for Discretion]

Consider the consequences. It’s not just the economic problems of rising debt and inability to respond adequately to the next recession or emergency. It’s also the political requirement imposed on you as legislators to renege on promises to the public and then facing its wrath in elections.

Yet, through inability to work together, both parties lose their agendas, getting government that is both fat and ineffective at meeting public needs.

For example, out of a scheduled increase of close to $12,000 annually per household scheduled in additional spending and tax subsidies by 2026, almost nothing goes for programs for all that encourage the development of earnings, wealth, human and social capital. And kids also get essentially nothing—NOTHING!

Restoring fiscal democracy requires nothing more or less than restoring greater discretion to the budget. Democrats must be willing to limit the share of spending on automatic pilot, and Republicans must do likewise for tax subsidies, while agreeing to collect enough revenues to pay our bills. And both the president and the Congress need to be held responsible for ALL changes in the budget, whether newly enacted or passively allowed to continue.

Restoring discretion does not simply mean paring program growth or raising taxes, but opening the door to modernizing programs to better meet public needs, including providing greater opportunity for all.

I am not naïve about the difficulty of reversing a multi-decade decline in fiscal democracy. Yet until we restore greater discretion to the budget, the frustration and anger faced by political parties and the public here and around the developed world will continue, deriving in no small part from a budget process that has shifted national debates from what we can do to what we can’t—that is, from letting dead men rule.

A version of this post originally appeared on TaxVox.

Empowering the Next President—and the Next Congress

Posted: June 3, 2015 Filed under: Columns, Economic Growth and Productivity Leave a comment »“This is a trade-promotion authority not just for President Obama but for the next president as well.”

That is how Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell explains his support for granting the president expedited authority to negotiate trade deals and fast-track through Congress a vote those deals. The authority would apply not only to an agreement negotiated by President Obama with several Pacific partners, but to agreements made through mid-2018 and potentially through mid-2021.

McConnell recognizes, at least in this case, that a president must have enough room to perform his executive duties. The Constitution provides the president with particular powers, including the negotiation of treaties. It makes no more sense for 535 members of Congress to negotiate treaties than it does for them to micromanage other tasks that should be left to the country’s chief executive.

I would like to extend McConnell’s thought beyond treaty making. Now is the ideal time to empower both the president and Congress to better perform their assigned functions: the president to execute and Congress to legislate.

Why? First—and obviously to even the casual observer—both branches of government have been weakened extraordinarily over recent decades by the politicization of every action and the growing influence of interest groups. Many impasses in both legislation and administration arise when one party thinks that it can diminish the other by imposing roadblocks. This thought is neither new nor unique to government; when an organization’s decisionmaking boundaries are ill defined and its members cross those boundaries to seek additional power, the organization often becomes dysfunctional.

Second, less than two years away from a presidential election with an uncertain outcome, elected officials more likely recognize, as Senator McConnell does, that maintaining roadblocks deters one’s own party’s likelihood of future success as much as that of one’s opponents.

Third, the last years of a presidency seldom focus on the changes that new power brings a political party. Yet it need not be a lame-duck period. It offers the opportunity to turn to those process reforms usually neglected when the political debate centers on bigger or smaller, rather than more effective, government. President, cabinet secretary, congressional leader, and committee chair alike should be examining their power and reorganizing both internally and across jurisdictions—or, quite bluntly, they are not doing their jobs.

Behind closed doors, almost every elected official will admit that many government systems are broken. Examples abound: Medicare continually out of balance, infrastructure and highways unfunded while bridges fall apart and trains crash, the inability to pass budgets or appropriations bills, a sequester requirement that must be overridden, and much more. These are process failures, not policy failures.

How might strengthening the hands of both the president and Congress improve the likelihood of solving such problems?

Medicare provides a good example. In the last presidential election, the candidates attacked each other for trying to constrain cost growth in what both knew was an unsustainable system. Governor Romney castigated the president for cutbacks that helped expand health insurance for the nonelderly, and the president attacked the governor for favoring a voucher-like approach put forward by then–House Budget Chair Paul Ryan.

In truth, all answers to the Medicare problem involve payment constraints. The program simply has to operate within a budget. Congress won’t create a budget for Medicare, but it won’t allow the president to use his executive power to do it either. Instead Congress passes the power of appropriating money onto our doctors and us as beneficiaries.

The fix is simpler than it seems. If the Democrats favor price controls for Medicare and the Republicans favor voucher-like approaches, then set up the general rules but let whoever attains executive power use it whenever spending starts to exceed a congressionally approved limit.

This method can work well in other arenas too. Congress can set guidelines for what it wants accomplished—certainly within a budget—but then it should allow the executive branch to fulfill those guidelines. If Congress over-constrains any particular function by demanding that more be done than allowed by the budget it sets, then the executive should be empowered to make changes necessary to restore balance. This is not rocket science, it is basic management theory.

In his acclaimed book The Rule of Nobody, Philip K. Howard similarly argues that the president must have executive powers restored, to be able to avoid wasteful duplication and unnecessary bureaucracy, to expedite important public works, to refuse to spend allocated funds when circumstances change and the expenditure becomes wasteful, and to reorganize executive agencies.

When Congress limits the president on executive matters, no matter how small, it isn’t empowering itself. Instead, it entangles itself in complex and contradictory legislation, attempting to appease every interest (no matter how small), while weakening itself as it spends less and less time tackling the big issues that it is elected to address.

All this does not let recent presidents off the hook. The constant expansion in political appointees and the centralization of power in the White House over several decades has led to even more roadblocks to progress. When every decision must go through several political layers, almost no good idea can filter through to the president. When so many public statements and decisions on millions of government actions must be fed through the White House, civil servants and even top political appointees can’t function well, and they often retreat to doing nothing risky and seldom attacking limitations or failures in their own programs. Among the further consequences, many excellent government officials retreat to the private sector. Who wants to work where you are not allowed to do your job?

Whether one agrees with the examples presented here matters less than recognizing the ripeness of this time for procedural reform. Senator McConnell is right. Let’s empower the next president—and the next Congress as well.