Tax Reform Isn’t Just About Revenue but Health Insurance, Housing, and More

Posted: July 21, 2017 Filed under: Columns, Health and Health Policy, Taxes and Budget 1 Comment »This post originally appeared on TaxVox.

Taxes aren’t just about raising money for government. Policymakers engaging in tax reform must recognize how their decisions can disrupt markets for a wide range of economic activity, including healthcare, housing, and charitable giving. Some of those behavioral reactions may be secondary and unintended, but they can’t be ignored.

The Tax Policy Center has described some of the potential impacts of President Trump’s tax ideas on charitable giving and in the way businesses organize themselves. But it’s worth looking at two other examples—health insurance and homeownership—to see how tax changes can affect economic behavior. In both examples, tax reform can improve efficiency and equity, but only if it is well designed.

Employer-provided Health Insurance.

In a recent press conference, Treasury Secretary Steven Mnunchin and Director of the National Economic Council Gary Cohn implied that Trump’s tax plan could limit existing tax breaks for employer-sponsored health insurance (ESI). It would be one of a long list of tax preferences that Administration may target.

But any significant cut in subsidies for ESI could lead employers to reduce or even eliminate health insurance as part of employee compensation. The effects of such a decision could be substantial and most likely change the way people get health insurance. Tax reform must be designed with regard to its effects on subsidies offered through the Affordable Care Act or the House’s recently passed replacement.

For many years, health policy experts have suggested replacing the ESI exclusion with a tax credit. But the ACA and the House bill, and their related costs, largely depend upon retaining the ESI exclusion while adding subsides for those who buy outside the employer market.

The ACA’s exchange subsidy is larger for many employees than the value of their exclusion. Thus, employers already have some incentive to drop ESI coverage, send employees to an exchange, and share the net savings. Yet, so far, few have done so in part due to uncertainty about the future of the ACA and the reluctance of managers to give up their existing coverage. It is not clear how employers would respond to tax reform under the ACA or the House’s credits, which are less generous but in some cases more flexible.

Tax Subsidies for Housing

Although Cohn insists that “homeownership would be protected” under Trump’s tax plan, the Administration is considering several proposals that would significantly reduce incentives to buy housing.

Here are just three examples: Lowering tax rates would make the mortgage interest deduction less valuable. Eliminating property tax deductions as part of a repeal of the state and local tax deduction could raise taxes for homeowners who itemize. And doubling the standard deduction would significantly reduce the number of taxpayers taking deductions for mortgage interest.

In this new world, renters would increase in numbers and the number of homeowners would decline.

Like the exclusion for employer-provided health insurance, the tax subsidies for homeownership are both inefficient and inequitable. They provide an incentive mainly to those who need it least because the benefits are concentrated among those with higher incomes.

While it might make sense as a matter of tax policy to give middle-income individuals a higher standard deduction in lieu of the opportunity to itemize expenses, does it make sense as a matter of housing policy to leave a mortgage interest deduction concentrated on a select few taxpayers, largely with incomes well above average? And to what extent should equity owners, who still maintain an incentive to own homes, as opposed to taking out their equity and putting it into a saving account, be favored relative to borrowers? After all, younger and wealth-constrained, households are the ones most in need of borrowed funds to own their first homes, and they already have a far smaller share of total societal wealth than they did a generation ago

Providing some alternative incentive, such as to new homeowners, might help address some of these housing policy issues.

My concerns are not intended to throw cold water on tax reform. But they are a warning about the importance of doing it right.

Tax subsidies for health insurance and homeownership do need reform, but policymakers must ask themselves whether their new tax system creates the right set of incentives for the right people and integrates well with spending programs aimed at the some of the same objectives. They must also be sure to adjust as necessary to avoid undesirable behavioral responses. If they don’t, they may weaken or even destroy the benefits of reform.

Replacing the Individual Mandate to Buy Health Insurance: A First Step to Compromise

Posted: July 14, 2017 Filed under: Columns, Health and Health Policy 1 Comment »This post originally appeared in TaxVox.

The Trump Administration and congressional Republicans remain stalemated over how to “repeal and replace” the 2010 Affordable Care Act (ACA). One major problem: The House approach in the American Health Care Act (AHCA) is highly unlikely to pass Congress when it increases the number of uninsured by 23 million, as estimated by the Congressional Budget Office. Real reform needs a better set of building blocks. Here I address one of those building blocks: how to replace the ACA’s individual mandate in a way that satisfies both Democratic goals for coverage and Republican concerns that government shouldn’t mandate what citizens must buy. What is the alternative? Simply make some existing government benefits, particularly tax benefits, conditional upon buying health insurance.

Such a step could also be made at least as progressive as the ACA’s mandate, which would please Democrats. And it would replace the use of a whole new penalty tax structure surrounding the ACA’s mandate, a step that should please Republicans.

Fair and efficient reform of ACA requires recognizing the logic behind individual responsibility to purchase insurance, an idea long favored by many researchers and public officials across the ideological spectrum. If government is going to support those in need, whether through Medicaid, uncompensated care, or, under some new government subsidy, how should it treat those who don’t buy health insurance even if they have the financial resources to do so? Equal justice suggests that a household making, say, $50,000 but effectively paying $10,000 to buy insurance—for instance, through lower cash compensation when receiving employer-provided insurance—shouldn’t have to subsidize other households with the same income but who don’t buy insurance.

That problem arises whenever government safety nets protect those who don’t insure against future needs but becomes particularly acute in health care when, as both Democrats and Republicans have now accepted, health insurance companies cannot exclude people with “pre-existing” conditions. Without some individual responsibility requirement, what is there to prevent people from going without insurance until they turn ill?

Democrats want to keep some requirement for individual responsibility to maintain the ACA’s coverage expansion. But why can’t Republicans find an acceptable alternative?

It’s simple math. Since adding millions to the roles of the uninsured seems politically unacceptable, the alternatives are to increase government benefits and the taxes needed to support them, or impose an even higher unfunded mandate on providers to care for the uninsured. Some commentators already believe that enactment of a House-like bill would eventually result in a universal system like Medicare for all, an unsatisfactory outcome for Republicans.

We are left with this: The federal government now spends about three-tenths of its entire non-interest budget on health care, and the share is increasing rapidly. In this expensive healthcare world, government supports should be targeted toward those who need help the most.

While the ACA’s mandate moves in the direction of establishing equal treatment of those with equal ability to buy insurance, it levies a penalty for most people that is far lower than the cost of insurance. According to a calculator provided by the Tax Policy Center, the 2016 penalty was $991 for a single person making $50,000 or $2,085 for a family of four. By contrast, the IRS indicates that an average “bronze” premium insurance policy would cost several times more: for an individual, about $2,700, and for a family of four, $10,700.

Making purchase of health insurance a condition for receiving other government benefits removes the philosophical and, for some, constitutional hang-up over whether government should mandate that we buy something. Instead, Congress could simply make health insurance a condition for opting to take some other benefits such as standard deduction, itemized deductions, or child credit. If we can get some more permanent agreement on some individual responsibility payment, the IRS can start to adjust withholding by employers for employees who don’t have employer insurance or declare otherwise that they have insurance. This would reduce end-of-the-year problems in collecting money from people who may not have any easy way to pay a penalty.

While some also suggest allowing insurance companies to charge higher premiums for those who buy insurance only when they get sick, that penalty is likely to be either too low to be effective or too high to be affordable by those who only seek insurance once sick.

In sum, any replacement structure for the ACA requires solid building blocks. Repealing and replacing the individual mandate with a conditional limit on the receipt of other government tax benefits offers one possibly bipartisan way to expand coverage, save government costs, and improve tax administration. To it, of course, must be added a subsidy system for those with too little income to afford insurance. The combination can be made as progressive or more progressive than the ACA. As noted, however, inattention to a requirement for individual responsibility will in the long run probably only add to the load that must be supported by the building block of government subsidies.

How the Fight over Symbols Prevents Health, Trade, Immigration and Tax Reform

Posted: April 25, 2017 Filed under: Columns, Health and Health Policy, Taxes and Budget 2 Comments »This post originally appeared on TaxVox.

President Trump came into office promising to repeal the Affordable Care Act, abandon key multinational trade agreements, build a wall and send immigrants home, and reform the tax code. Many Democrats have sworn to oppose him at every turn. On the first three items, he has already faced obstacles or stalemate and even temporarily left the battleground. But are these debates really about substantive reform that improves people’s lives? Or mainly over capturing symbols that appeal to each party’s base? Those goals aren’t the same.

Reform defies easy party or ideological labels because it often focuses not on bigger or smaller government but fixing poorly-functioning operations, establishing greater equity among households, or adapting to new circumstances. With health, immigration, trade, and tax policy the need for constant real improvement conflicts with important, but often-counterproductive, fights over political symbolism.

Health Reform. When the Affordable Care Act (ACA or Obamacare) passed the Senate, backers knew it had flaws. They hoped to fix them later in the legislative process, but the death of Sen. Ted Kennedy cost Democrats their filibuster-proof majority in the Senate and made the fixes or amendments requiring a new Senate vote virtually impossible. As a result, the healthcare community and households continue to grapple with an imperfect environment: Gains from expanded insurance coverage have been offset by slower than expected take-up rates, especially among young adults, for ACA marketplace policies, ongoing uncertainty about Medicaid expansions, and failure to come to grips with the full impact of health cost growth, often outside of Obamacare, on the federal budget.

Congress and President Trump have a chance to repair those problems, but both parties find themselves in a box. Republicans can’t accept any reforms that allow Democrats to claim “Obamacare” is being preserved, while many Democrats can’t swallow changes that acknowledge the ACA’s failures.

Trade Reform. Trade is another case where political symbolism impedes needed change. No doubt, our trading partners at times violate the spirit and even treaty letter of “fair” trade (so does the US), but trade agreements are the very vehicle for limiting such violations. Rather than repairing these understandings, political symbolism demands they be torn up or abandoned. Thus, instead of reviving and revising the Transpacific Partnership, which might have enhanced US trade in Asia, the Trump Administration has scrapped it.

Any successful trade agreement must strengthen rather than weaken international commerce if it is to promote economic growth without raising consumer prices. But trade debates occur on treacherous political ground. Any shift in trade, no matter how good or bad, almost inevitably reduces demand for some US-made products and hurts the workers producing those goods, thereby creating a new group of populists who will cry “foul” that the President and Congress have once again abandoned workers.

Immigration Reform. People suffering from persecution, hunger, or lack of human rights will try to escape those horrors and find new opportunity. So it has always been and will always be. Borders are porous enough that there are tens of millions of immigrants, legal and illegal, in the United States and much of Europe. Meanwhile, immigrants grow as a share of developed nations’ total populations, partly due to relatively low-birthrates in the existing populations. We can reduce opportunities for legal entry, step up border patrols, build walls, and send even more people back to their prior country of residence. But none of those actions really address the basic economic and social forces at play, while temporary symbolic political victories leave millions of families fearful of breakup, reduce domestic output by immigrant workers, and hurt America’s image as the home of freedom for people around the globe.

Tax Reform. In taxation, the symbolic fights almost always center on the size of government and progressivity. Yet many of the tax code’s real problems are that it is inefficient, complex, and treats those with equal incomes unequally and inequitably. The Tax Reform Act of 1986 neatly focused on the latter issues by making no significant change in either revenues or progressivity. But even in its early stages, the debate over a 2017 tax reform has already been muddled by a cacophony of mutually inconsistent goals: Reduce tax rates for multinational corporations and cut taxes for the middle class while not increasing the deficit or raising anyone’s taxes.

As long as lawmakers fight mainly over symbols rather than substance, they are unlikely to achieve many real improvements in policy. And tax reform will follow along the path down which health, immigration, and trade reform already seem headed.

Health costs, not Obamacare, dominate the future of federal spending

Posted: July 1, 2016 Filed under: Health and Health Policy 1 Comment »A version of this post originally appeared on Health Affairs.

From all the political discussion about health care, you’d think that government health policy lives or dies by what happens to the Affordable Care Act, or Obamacare. One side offers almost nothing apart from saying Obamacare must (somehow) be abandoned. The other side tells us that health costs, partly thanks to Obamacare, might be under control. Neither side faces up to the continuing dominance of health costs in projections of future federal spending.

Meanwhile, a recent study suggests yet again that spending much more on health care may do little to improve mortality and opportunity for the disadvantaged.

Like most debates that become political, the discussion tends to be numberless. Numbers aren’t always popular for those whose facts must fit their storylines, as opposed to those whose storylines evolve from the facts.

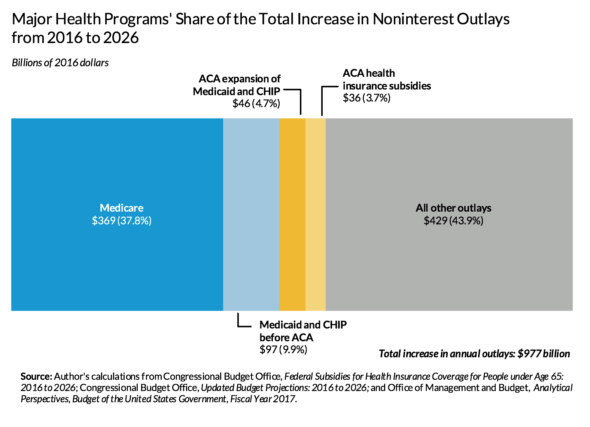

So what do the numbers tell us? Figure 1 shows that health care spending composes most of all projected increases in noninterest outlays of the federal government, but that Obamacare for those under age 65 is only a moderate cause of this growth.

Note: Because I focus on health costs, not on how we pay for them, calculations exclude payments made by taxpayers to support these programs, such as Medicare Part B premiums that budget analysts sometimes net from gross outlay payments. Allocation of costs or changes in costs over time because of Obamacare may exclude potential secondary impacts, such as a shift out of employer-provided health care or a change in Medicaid costs for people over age 64.

The health spending problem is still with us

Despite slower health spending growth, we have not solved our health spending problem. In 2026, the federal government is expected to spend (and subsidize through the employer coverage tax exclusion) at least $693 billion (in 2016 dollars) more than today for major health insurance programs. If we exclude the tax subsidies (as the exhibit does), this sum decreases, but only to $548 billion.

Excluding interest on debt, federal outlays for major health programs (excluding tax subsidies, which aren’t counted in outlays) eat up around 29 percent of today’s total federal outlays but about twice as much—56 percent—of the growth in total outlays between now and 2026 (figure 1).

Turning to the economy more broadly, for every additional dollar of real gross domestic product per capita expected 10 years from now, 20 cents will go toward supporting the rise in federal health insurance programs costs. And even these numbers significantly understate growth in total health costs by leaving out state and local health costs, other federal costs such as health research, and private spending on health care. Adding these other costs would indicate that health care continues to eat up a very large fraction of economic growth. Much of the confusion here about whether “health cost growth has slowed” occurs because lower economic growth tends to reduce the growth rate of all spending items, including health care, but not necessarily the share of growth absorbed by health care.

The relatively minor role of Obamacare

Obamacare has very little to do with any of this. If we include growth in tax subsidies for health insurance, Obamacare programs for those younger than 65, including Medicaid expansion and new health insurance subsidies in the Marketplace, entail only about 8 percent of the federal government’s cost for major health programs and 12 percent of the projected increase in annual cost within a decade. And even those additional Obamacare costs are offset partly by cuts established in the Affordable Care Act.

In contrast, growth in Medicare makes up half or more of all federal major health program spending and of the projected increases; the tax break for employer-provided insurance and the Medicaid program for those eligible before Obamacare also entail significantly higher costs than does Obamacare.

Moving forward

We have a long way to go in reforming health care and health care costs. Such reform must tackle all elements of what I have labeled our four-tranche system of federal subsidies: Medicare, Medicaid, employment-based subsidies, and the exchange subsidies established in Obamacare. We must also remember that the goal of reform is not simply to reduce costs but to shift resources to where public gains are expected to be higher, including preventing health problems before they arise.

Copyright ©2015 Health Affairs by Project HOPE – The People-to-People Health Foundation, Inc.

My Christmas Wish List: I Want to Be a Drug Company

Posted: December 3, 2015 Filed under: Columns, Health and Health Policy, Taxes and Budget 3 Comments »When I was a kid, I asked Santa to bring me a bike or a baseball glove. As an adult, I mainly wished for good health and good cheer for myself and my loved ones. This year, I have a particular request that I hope the man in the red suit can grant: I want to be a drug company.

I want the government to give me a monopoly over what I produce. I want to be able to set almost any price for my products.

I want the government to pay for whatever tens of millions of government-subsidized customers buy from me. I also want the government to pay those who sell my product or spend their time advising and prescribing my product for others.

I want to be paid for years and decades for producing the same thing to meet some chronic need, even if it would be better to produce things that heal or cure. I want to be paid for things that sometimes turn out to be worthless, and to avoid the possibility of my customers haggling over prices or suing me because they don’t pay for those things directly.

I want Congress to give me the power to appropriate money to myself and give up some of the power reserved in the Constitution for itself.

But I’m not done.

I want the government to let me avoid paying tax on the income I earn from the money it pays me. I want to be able to live in the United States and claim citizenship for tax purposes abroad in some low–tax rate country. I want to defer taxes on my income, then have the government forgive that tax debt. And I want congressional representatives who for years—even decades—have been more interested in fighting among themselves than in doing anything about this type of arrangement.

Why not? A recent news flurry surrounds Pfizer’s announcement that it will now become a foreign company so it can avoid US corporate tax and grab money set aside abroad for US tax liabilities. But that’s only the tail on a long list of favors granted it and other drug companies.

I write a lot. Imagine if I put my work under copyright, then lobbied to have a law passed that creates millions of subsidized customers who can have my work for free because I’m billing the government. Of course, I should be allowed to set almost any price for what the government pays on behalf of those customers. And the government could promise to book and magazine sellers that their profits would rise automatically with sales of my writings. Meanwhile, I’ve been around long enough that I’ve got a good share of my income deferred from tax until I draw down my 401(k) accounts, so I should be allowed to rent a shack somewhere abroad, claim a foreign residence, and avoid ever paying tax on that income, even while I live in the States.

Now, don’t blame me if I respond naturally to all those incentives. Or lobby Congress to maintain them. And don’t blame me if I end up producing things less worthwhile than what I could produce. Hey, it’s a free country.

How about you? Maybe together we can invent a company for workers and could be granted power to charge anything we want for providing that work to a large set of government-subsidized customers. We shouldn’t have to pay tax, given all we are doing for the economy. We could get some deep-thinking consulting firms to prove that this would probably solve any future unemployment problem.

What do you say, Santa? For goodness sake, you know I’ve been good, and I’m not pouting. With this wish, I’m just asking for what your competitor, Congress, gave the drug company next door.

Millennials: Today’s Underserved, Tomorrow’s Social Security and Medicare Bi-millionaires?

Posted: September 16, 2015 Filed under: Aging, Columns, Health and Health Policy, Income and Wealth 2 Comments »When America’s Social Security system was first established in 1935, the public was deeply concerned about the fate of our elderly, who were then on average poorer than the rest of the population, less capable of working, more likely to work in physically demanding jobs, and less likely to live close to two decades past age 65. Today’s concept of Social Security was actually only one part of an act aimed at meeting the needs of the poor, old, needy, and unemployed of all ages.

In the early decades through the 1960s, Congress expanded old-age supports largely to cover important gaps such as spouses and survivors, disability, health insurance and inflationary erosion of benefits. Today, however, Social Security grows based on past laws that preordain increases in old-age support, largely independent of how the needs of the elderly and nonelderly have evolved or will evolve.

In a newly released study, Caleb Quakenbush and I find that a typical couple retiring today is scheduled to receive about $1 million in cash and health benefits; many millennials will receive $2 million or more. In effect, we’ve now scheduled many young adults to be future Social Security and Medicare bi-millionaires. And the growth continues; the succeeding generation, born early in the 21st century and sometimes referred to as the homeland generation or generation Z, is scheduled for significantly higher benefits. Add to these amounts additional Medicaid expenditures that also go to many elderly if in a nursing home for any extended period of time. (These figures are “discounted”—that is, they show what amount would be required in a saving account, at age 65, earning real interest, to provide an equivalent level of support.)

In fact, a very high proportion of all growth in federal government spending over the next several decades is currently scheduled for Social Security and Medicare. Almost all other spending, whether for children or defense, infrastructure, or the basic functions of government, already is held constant or in decline in absolute terms, and sometimes in a tailspin relative to the size of the economy and the federal government. Only other forms of health care and retirement support, interest costs, and tax subsidies are on the rise.

Such developments are hardly sustainable. Simple math tells us that they will continue to impose costs that the millennials and younger generations are already experiencing: cuts in other benefits for them and their children, higher taxes, and reduced government services when they are in school, working, or middle-aged.

Next time you read a headline on growth in student debt, the falling real value of the child credit, declines in federal spending on education and infrastructure support, or fewer soldiers and sailors, keep in mind that these stories all follow as a consequence of where past Congresses have directed almost all government growth. Of course, governments almost always spend more as an economy and the tax base expand, whether the size of government relative to the economy grows, stays constant, or declines. But past governments traditionally allowed future legislators and voters to choose what to do with those additional revenues; they weren’t stuck with leaving that decision to prior legislators.

How did we get here? As Congresses and presidents added to Social Security over the years, it became more generous. Health insurance was expanded to cover hospitals and doctors, then more recently under President George W. Bush, drug benefits. Cash benefits were raised through various enactments under Republican and Democratic presidents alike.

One big culprit is the retirement age, which, by remaining stable on the basis of chronological age, does not remain stable on the basis of years of support, which increase as people live longer. A typical couple retiring at the earliest retirement age now receives benefits for close to three decades, which is roughly the expected lifespan of the longer living of the two. Spend $25,000 (discounted) per year on each person, but then do it for 20 years or so per person, and you come up with a figure like $1 million for a couple.

Since the 1970s, real annual benefits have also been growing automatically as wages rise. In fact, the combination of “wage indexing” and failure to adjust for life expectancy schedules Social Security to rise forever faster than the economy.

Then, of course, there are the health care costs. People are getting more years of medical support as they live longer. Plus, the federal government has never effectively tackled the increasing costs that result almost inevitably in a system where you and I can bargain with our doctors over whatever everybody else should pay to support our next procedure or drug.

By the way, none of these calculations account for the decline in the birth rate and its effect on the number of workers available to support such benefit growth. Roughly speaking, the taxes available to support any system decline by about one-third when the ratio of workers to retirees falls from 3:1 to 2:1.

We’ve traveled a long distance from 1935’s legislation and its goal of addressing the needs of people of all ages.

Why Health Cost Growth Increases after Estimators Say it’s Slowing: Observer Effects and Feedback Loops

Posted: August 3, 2015 Filed under: Columns, Health and Health Policy 2 Comments »“Health cost growth has slowed down, we think. So let’s increase health costs.” This is the federal government’s apparent response to some recent sanguine estimates about the future of health cost growth. We might call this response a policy version of the “observer effect,” where the mere observation of reality changes that reality. In this case, the observation that health care costs may be increasing more slowly than expected creates a political reality in which fewer efforts are exerted to keep costs under control.

Projections based on past historical trends are fraught with danger. The influence of government policy sits near the top of that danger list. Since federal and state spending plus tax subsidies now cover about 60 percent of the health care budget, government legislation decides much of what the nation will pay for health care. Speaking technically, policy is endogenous to—or influential on—the past trends we measure.

Logically, then, future legislation too has a powerful effect on the direction of health costs. But possible policy changes are an unsteady foundation for cost projections. Government agencies like the Congressional Budget Office try to get around this dilemma by treating policy as exogenous to—or not influencing—cost projections. That way, those agencies can display the implications of current laws, even when those laws imply a growth in cost that is unsustainable.

But health researchers, the public, or elected officials who conclude that past trends will simply continue often fail to account for how policy decisions feed health costs and vice versa. US health care insurance, including that provided or subsidized by government, still offers fairly open-ended access, allowing consumers to spend more and providers to earn more at others’ expense. If policymakers interpret slower cost growth to mean they need fewer new cost-reducing measures and can even rescind some old ones, then as a consequence health costs are going to rise faster.

It now seems clear that Congress and the Obama administration have responded to these new estimates by taking a more lackadaisical attitude toward controlling costs. Two pieces of evidence:

- Congress has long squabbled over how to deal with legislation that tried to make the growth in Medicare costs sustainable by cutting payment rates to doctors for certain procedures. Past efforts led to “doc fixes” that held off such cuts for a while and let them accumulate. All was not lost: according to the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, these annual forestalling actions involved significant other health cost cuts to pay for each fix. In 2015, however, Congress threw in the towel: it abandoned the old requirements on doctors while providing limited real offsets.

- Many Republicans and some Democrats now oppose a tax imposed under Obamacare that requires insurance companies to pay a tax on high-cost insurance plans (plans whose value exceeds $27,500 a year for a family and $10,200 a year for an individual in 2018). Admittedly an imperfect device, the tax did address both conservative and liberal concerns, backed by solid research, that offering a tax subsidy for costs above a cap mainly led to higher health care costs while doing little to expand coverage. Abandoning the high-cost plan tax would effectively increase health costs even more.

Harder to substantiate are cost-controlling initiatives that are abandoned or never undertaken. For instance, President Obama has removed some of the health saving initiatives that used to be in his budget—such as limits on state gaming of Medicaid matching rates—presumably because he thought these initiatives were unlikely to get through Congress, or he had enough health care fights on hand. How much have payment advisory commissions felt that they could let up on new suggestions to reduce prices? In general, how does a perceived reprieve from pressure lead any of these actors to kick the can down the road to their successors or at least until after the next election? Paul Hughes-Cromwick of the Altarum Institute also asks whether something similar doesn’t go on in the private sector: for example, would specialty drug makers price new entries so aggressively (e.g., Sovaldi for Hepatitis-C or even Jublia for toenail fungus) if we weren’t simultaneously coming off historically low spending growth?

My advice to estimators: include a feedback loop to demonstrate how your estimates affect the behavior of those making decisions on the basis of your estimates. Your projections of lower health cost growth may end up increasing health costs.

A Better Alternative to Taxing Those Without Health Insurance

Posted: March 6, 2015 Filed under: Columns, Health and Health Policy, Taxes and Budget Leave a comment »Although the public debate on health insurance coverage centers on a thumbs-up, thumbs-down fight over the Accountable Care Act (ACA, also called Obamacare), our national system needs a lot of smaller fixes. Many items on this long list of fixes make sense under either a Republican alternative to Obamacare (like the one recently but only partially laid out by Representative Paul Ryan) or Democratic amendments to the existing plan. One example: rethinking the tax penalty on people who do not buy insurance, an issue receiving increased attention as the IRS assesses its first penalties. We can achieve the same end much more effectively by requiring households to purchase health insurance if they want to receive the other government benefits to which they are entitled. No separate tax is required.

The history of the tax penalty

A system of near-universal insurance—where most people of the same age, regardless of their health conditions, can buy insurance at approximately the same price—needs a backup. This need became clear when health reform proposals were first introduced in 2009. Without a backup, individuals have a strong incentive to avoid buying insurance until they are sick, thus effectively getting someone else to pay for their health care. This incentive exists regardless of income level: even a wealthy person who buys health insurance only after becoming sick could hoist his bills on those with lesser incomes who pay for insurance year-round and every year.

The ACA’s partial response to this incentive is to tax those who fail to buy health insurance. The tax for failure in 2014 was either 1 percent of income or $95 per person; it rises to 2.5 percent of income or $695 (adjusted for inflation) after 2015. At the beginning of 2015, millions of people discovered that they owed this tax as they started filing their federal tax returns for 2014.

Practical considerations have always led toward some individual requirement to buy insurance, simply because there are limits on how much government can spend on subsidizing everyone. Our very expensive health care system now entails average health costs per household of about $24,000. The federal government would have to spend just about all its revenues trying to cover all those costs. A mandate to purchase insurance is a partial alternative to ever-more subsidies—as Governor Romney knew when he implemented a related mandate in Massachusetts. At one point, the mandate idea was favored by conservatives even more than liberals as a way to avoid an even more expensive government-controlled system, such as Medicare for all.

What might work better

The problem with the Obamacare tax penalty isn’t the idea; it’s the design. This problem, in various forms, occupied the federal courts needlessly. The central dilemma that pre-occupied an earlier Supreme Court decision was whether government could mandate that we had to buy some particular product (maybe not, it said, but, at least in Chief Justice Roberts’ opinion, it could impose a tax).

Another type of requirement avoids many past and current issues surrounding the Obamacare tax penalty. Simply deny to taxpayers other government benefits if they do not obtain insurance for themselves and their families. There has been no debate over whether government can—indeed, at some level administratively must—set conditions for determining who receives benefits.

This type of requirement could be implemented in various ways. The personal exemption or the child credit or home mortgage subsidies could be limited; some portion of low interest rates for student loans could be denied. This approach entails no new “tax” for not buying insurance; it simply adds to the conditions for receipt of other government benefits.

Designed well, the denial of any tax benefit could easily be reflected in withholding, so there are fewer end-of-year surprises. Employers, for instance, could adjust withholding for months in which employees did not declare insurance for themselves. As for the many poor receiving benefits like SNAP, most tend to be eligible for Medicaid, so the requirement than they sign up could be handled better by the related administrative offices that deal with them than by the IRS imposing some surprise penalty at the end of the year.

For both administrative and political reasons, this type of requirement can also be made stricter than the current extra tax. The IRS has always had trouble collecting money at the end of the year, and people react more negatively to an additional tax than to a requirement that they shouldn’t shift health costs onto others if they want to receive some other government benefit.

The road ahead

I doubt that any future government, Democratic or Republican, is going to deny people the ability to buy health insurance at a common community rate, even if they are sick or have failed to purchase health insurance previously. The world has already changed too much. Insurance companies have adapted, and so have hospitals. Before health reform, uninsured people could generate partial benefits or coverage by receiving treatment in emergency rooms (where such care is often required by law), and then not paying their bills. With some major exceptions, that practice has declined since the ACA was implemented. No one wants to go back to the old ways.

In a partisan world, of course, a fix of almost any type becomes difficult. Republicans are afraid to fix almost any aspect of Obamacare for fear it would involve a buy-in to the plan’s success; Democrats dread amending Obamacare because it might hint at some degree of failure. Watching the current Supreme Court battle, you sense that many enjoy the fight more than anything else. Still, this simple fix should be added to the list of reforms for consideration when and if we decide we want something better.