How Government Tax And Transfer Policy Promotes Wealth Inequality

Posted: February 8, 2019 Filed under: Columns, Income and Wealth, Taxes and Budget Comments Off on How Government Tax And Transfer Policy Promotes Wealth InequalityFederal tax and spending policies are worsening the problem of economic inequality. But the tax breaks that overwhelmingly benefit the wealthy are only part of the challenge. The increasing diversion of government spending toward income supports and away from opportunity-building programs also is undermining social comity and, ironically, locking in wealth inequality.

Many flawed tax policies are rooted in the ability of affluent households to delay or even avoid tax on the returns from their wealth. By putting off the sale of assets, wealth holders can avoid tax on capital gains that are accrued but not realized. At death, deferred and unrecognized capital gains are exempted from income tax altogether because heirs reset the basis of the assets to their value on the date of death.

While individuals and corporations recognize taxable gains only when they sell assets, they may immediately deduct interest and other expenses. This tax arbitrage makes possible everything from tax shelters to the low taxation of the earnings of multinational companies.

Recent changes in the law have further eroded taxes on wealth. Once, the US taxed capital income at higher rates than labor income, today it does the reverse. For instance, the 2017 tax law sharply lowered the top corporate rate from 35 percent to 21 percent, but trimmed the top individual statutory rate on labor earnings only from 39.6 percent to 37 percent.

In theory, low- and middle-income taxpayers could use these wealth building tools as well. But the data suggest that the path to wealth accumulation eludes most of them, partly because they save only a small share of their income. Even those who do save $100,000 or $200,000 in home equity or in a retirement account earning, say, 5 percent per year may never reap more than $1,000 or so in tax savings annually.

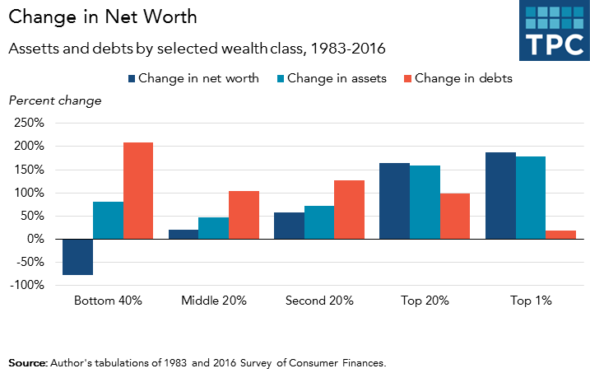

To understand what has been happening to the relative position of the non-wealthy, we need to dig a little into the numbers. Economics professor Edward Wolff of New York University discovered that in 2016 the poorest two-fifths of households had, on average, accumulated less than $3,000 and the middle fifth only $101,000. Trends in debt tell part of the story. From 1983 to 2016, debt grew faster than gross assets for most households–except for those near the top of the wealth pyramid.

It’s not that the government doesn’t aid those with less means. But almost government transfers support consumption, and only indirectly promote opportunity.

Consider the extent to which the largest of these programs, Social Security, has encouraged people to retire while they could still work.

Because of longer life expectancy and, until recently, earlier retirement, a typical American now lives in retirement for 13 more years than when Social Security first started paying benefits in 1940.That’s a lot fewer years of earning and saving, and a lot more years of receiving benefits and drawing down whatever personal wealth they hold.

Annual federal, state, and local government spending from all sources, including tax subsidies, now totals more than $60,000 per household—about $35,000 in direct support for individuals.Yet, increasingly, less and less of it comes in the form of investment or help when people are young. Thus, assuming modest growth in the economy and those supports over time, a typical child born today can expect to receive about $2 million in direct assistance from government. In the meantime, however, government has (a) scheduled smaller shares of national income to assist people when young and in prime ages for learning and developing their human capital, (b) reduced support for their higher education in ways that has now led to $1.4 trillion of student debt being borne by young adults without a corresponding increase in their earning power, and (c) offered little to bolster the productivity of workers.

Any number of programs could have a place in encouraging economic mobility, among them beefed-up access to job training and apprenticeships for non-college goers; wage subsidies that reward work; subsidies for first-time homebuyers in lieu of subsidies for borrowing; a mortgage policy aimed more at wealth building; and promotion of a few thousand dollars of liquid assets in lieu of high-cost borrowing as a source of emergency funds — you get the point. However, in one recent study, I found that federal initiatives to promote opportunity—many in the tax code—have never been a large fraction of government spending or tax programs and are scheduled to decline as a share of GDP.

It would be naïve to assume that fixing any of this will be easy. Republicans seem committed to reducing (not increasing) taxes on the wealthy, while Democrats reflexively support redistribution to those less well off, even when their proposals reduce incentives to save and work. But until we fix both sides of this equation, don’t expect government policy to succeed in distributing wealth more equally. After all, simply leveling wealth from the top still will leave the large number of households holding zero wealth with zero percent of all societal wealth.

This blog also appears on TaxVox. A longer version of this blog can be found in The Milken Institute Review, 21 (1): 16-27.

Come The Flood, Who Should Pay To Help?

Posted: September 6, 2017 Filed under: Columns, Income and Wealth, Taxes and Budget 1 Comment »This post originally appeared on TaxVox.

Hurricane Harvey’s historic flooding has brought out the best in many people. They have put their lives in danger to save strangers, shared their food, and offered their homes. Citizens across the country are contributing to the United Way, Red Cross, community foundations, and churches. Race, creed, and social status seem to make little difference, and the political issues that divide us suddenly seem petty, almost separated from the real world in which we live, suffer, or thrive.

But because charities and individuals can do only so much, we have turned to government to act on our behalf. But even as we ask government to coordinate efforts and bear a large share of the cost of repair and rejuvenation, a question lingers: Who should pay for those costs? Or to ask another way, who should feel entitled to claim they are exempt from the social compact that says we should use our tax dollars to assist victims of an historic flood they could not predict or plan for? Once one broadens this question to include helping victims of poverty or poor health, or paying some share of the cost of our national defense, it lays bare the issue of who should pay taxes.

Join me, therefore, in speculating about who should be exempt from sharing in the tax burden for helping victims of Hurricane Harvey.

How about owners of capital? They claim they benefit society by building and holding onto wealth and promoting growth by investing that wealth. Though often exaggerated, their case has enough merit to support economic and legal arguments for converting the income tax to a tax on consumption. Indeed, our current tax system combines features of both and reflects the divisions over the role of savings and investment in enhancing our well-being.

Many owners of capital even claim they should pay “negative” tax rates, at least on returns from new investments through generous tax depreciation or expensing of debt-financed physical assets. Should the tax system exempt owners of capital who consume only modest portions of their income from helping to finance assistance for the victims of Harvey?

How about the poor? We exempt low-income households from income tax (though the poor often pay sales, excise, and payroll taxes), a choice that also has some merit. After all, how can one expect the poor to pay taxes when they can’t afford adequate food or housing? Of course, that issue is complicated because low-income people often receive more in government support than they pay in taxes.

How about the middle class? We’re running huge federal deficits today largely because no one wants to raise their taxes or cut their benefits. Democrats are willing to tax the rich and Republicans will take away benefits from the poor, but both parties appear to coddle the (very large) middle class. It is true that middle-income workers have seen little wage growth or upward mobility in recent years, but does that mean they should not do their part to help government cover the costs of floods or other public goods and services that otherwise would add to deficits?

How about the elderly? Yes, many are retired and on fixed incomes. But many are reasonably well off and enjoy a permanent tax exemption on income from sources such as Roth retirement accounts. Can we as a nation go back on that deal? How about those who die with large estates? They could have realized income by selling assets and consumed that wealth when alive. But if they did not, should they be subject to an estate tax upon death? How about companies that get special business tax breaks? Don’t they need tax help to ensure their competitiveness with firms in other countries?

And, finally, how about you and me? Why should we have to pay taxes when it appears almost nobody else does? But then there are those people suffering in the wake of Hurricane Harvey.

Did the Financially Insecure Secure Donald Trump’s Victory?

Posted: December 21, 2016 Filed under: Income and Wealth, Job Market and Labor Force 1 Comment »

In a classic case of Monday-morning (or Wednesday-morning) quarterbacking, many of us tend to seek one simple explanation for why Donald Trump won the recent presidential election. New analysis from some of my colleagues at the Urban Institute shows that the real reasons are more complex and transcend sound bites.

As part of our Opportunity and Ownership Initiative, Diana Elliott and Emma Kalish have assessed ongoing election narratives with some on-the-ground facts and an interactive map. They compare county-by-county elections results with various financial and demographic characteristics of voters. Interestingly, Diana and Emma conclude that financial insecurity did not drive voting preferences.

In fact, Hillary Clinton won just 4 of the 55 counties (or county equivalents) whose residents had the highest average credit scores (720 and above). High credit scores imply bills paid promptly and the type of financial stability that comes with paying off a mortgage over time. Clinton did win the 11 counties with the lowest scores.

Race and education were strong factors: generally speaking, white consumers were more likely to vote for Trump, those with bachelors’ degrees or higher to vote for Clinton.

These results provide information not only about voting patterns but about whether different policy initiatives would help those who feel ignored or left out by government, another part of the post-election debate. Further research might also reveal whether Trump appealed to people living in regions that had suffered some decline in security or population, even if voters’ relative financial standing in November 2016 was average or better.

If you access the interactive map yourself, you can do your own analysis of many interesting—and sometimes surprising—factors and see results for particular counties and regions.

Reducing Wealth Inequality Requires Holding Risky Assets

Posted: September 29, 2016 Filed under: Economic Growth and Productivity, Income and Wealth 5 Comments »How do people build wealth? How do low-wealth families climb the economic ladder? It’s simple. They save. They get decent or even above-average returns on their savings. And they reinvest those returns over time. Unless policymakers and advocates face up to these simple propositions, policy efforts to reduce wealth inequality will go for naught.

Over many years I have had the privilege of working with groups concerned with wealth inequality and promoting asset growth. One of them, the Corporation for Enterprise Development, has been holding its biennial Assets Learning Conference, engaging over one thousand professionals. I cofounded and work with the Urban Institute’s Opportunity and Ownership initiative, which researches wealth inequality. Because of their concern for the well-being of low-income, low-wealth households, these engaged individuals often try to figure out ways that government can simultaneously support and protect more vulnerable populations. One consequence, though, is a hope and sometimes belief that asset-building policies can increase wealth without reducing consumption and can generate higher returns without requiring risk taking.

But saving by definition means forgoing consumption. Even if government provides the money, it forces individuals to save rather than immediately spend that money.

This fact creates a controversy among progressive advocates. A dollar spent on wealth building means a dollar not spent on food, health care, or other transfers for immediate needs.

Finance 101 further teaches that higher returns on saving come from investment in riskier assets. The expected return on stock is higher than the return on bonds, and the expected return on bonds is higher than the return on savings accounts and Treasury bills. Over several decades the after-inflation investment return on corporate stock has averaged close to 6 percent, whereas the return on five-year government bonds sits at around 2 percent. The expected return on many saving and checking accounts is close to zero. Compounded over time, average stock market investors will see their money multiply about eight times after 36 years; average medium-term bond investors will see theirs double. Savers using only checking and saving accounts, meanwhile, will see little if any growth.

Over short periods, however, stocks have the highest risk of the assets just mentioned, while savings accounts have the least. Over very long periods, the risks reverse. Investing in the stock market is like flipping a coin bent enough that betting on heads on average nets a good return, but there’s a high probability of a loss with a few flips. As the number of flips increase, the odds of having more heads than tails get better and better. John Bogle, founder of Vanguard, said it like this: “The data make clear that, if risk is the chance of failing to earn a real return over the long term, bonds have carried a higher risk than stock.”

It’s possible to buy stock and insure against losses relative to, say, a short-term bond. But the insurance will cost the difference in returns plus additional transactions costs. Thus, attempts to provide low- and moderate-wealth households both higher returns and low risk tend to fail.

Just look at the household assets reported on wealth surveys. Wealthy households hold the vast majority of their wealth in stock and small business assets and real estate either directly or through retirement accounts. They make much of their money not just by saving more initially, but by allowing the saving on higher-return assets to compound. Low-wealth households, meanwhile, own few or no high-return assets, tend to hold more debt relative to their incomes, and often pay higher interest on that debt.

Timing matters, too, especially when it comes to large, infrequent purchases like buying a home. Mortgages became widely available to lower-income households in the early 2000s, when home prices were at a peak, but less available after the Great Recession, when prices were lower and owners were getting capital gains in many regions. As Bob Lerman, Sisi Zhang, and I have pointed out, this created a “buy-high, sell-low” mortgage policy that devastates low-wealth households, including the young.

The policy implications are clear. Simply taxing the rich more or distributing more to low-wealth households will do little to narrow wealth inequality. Transfer programs rarely encourage wealth-holding and may even exacerbate private wealth inequality by imposing asset tests and by favoring renting over homeownership.

None of this means that the rich shouldn’t pay higher taxes or that transfer programs don’t protect vulnerable families or even provide a type of “asset” in the form of income and risk protection. That’s another subject. The subject here is the distribution of private wealth and the power it brings.

Advocates and lawmakers trying to counter wealth inequality, therefore, must find ways to get low-wealth savers into longer-term assets like stock and real estate, mainly through retirement plans and homeownership. Small business ownership also matters. And, subsidies provided by government must encourage long holding periods—that is, saving over time, not short-term deposits. Deposits followed quickly by withdrawals or loans don’t increase saving. Nor do proposals that subsidize borrowing encourage homeownership, since, by encouraging more borrowing, they often reduce net home equity.

Of course, many low-wealth households are not ideal investors in riskier assets. But there are risks and there are risks. Remember that Social Security and Medicare—and, to some extent, traditional pension plans—already require nonelderly adults, whatever their other needs, to “save” some income today to prevent inadequate income in old age.

Successful investment requires forgoing consumption, taking risks, and adopting a long-term view. Those attempting to address wealth inequality must either recognize these fundamental facts—and the related costs involved—or fail in their mission.

Photo by 401(K) 2012 via Flickr Creative Commons.

A Universal Basic Income? Right Debate, Wrong Answer

Posted: June 22, 2016 Filed under: Income and Wealth 1 Comment »Recently, advocates have revived and extended an old idea: that government should give everyone, regardless of their economic circumstances, a universal basic income (UBI). For instance, each single person would get a government cash payment of, say, $12,000, which is just above the official poverty level of $11,700. The benefit would reduce, or perhaps replace, current government tax and benefit programs aimed at low-income households.

The proposal raises some important questions about how government should help people avoid poverty and more generally support almost all of us who get government benefits of one type or another. While some critics wonder whether such an ambitious idea is affordable, I’m more concerned about whether society would be better off if government used the money to create opportunity for those who are struggling financially.

Progressive supporters of UBI see it as a way to eliminate poverty by redistributing more money from the rich. Those on the right say it could replace costly and administratively inefficient welfare-type programs. Adherents include Andy Stern, former head of the Service Employees International Union, and a growing group of Silicon Valley executives, such as Sam Altman, president of Y Combinator, a venture-capital firm which is funding a pilot program to research UBI in Oakland, CA.

The goals of reducing both poverty and inefficiency are worthy. But we want to be sure we don’t discourage work in an economy already facing unprecedentedly low levels of labor force growth. And while combining and simplifying programs makes sense, it can’t be done in one easy step.

Think about how complex low-income support programs have become since Milton Friedman and my mentor Robert Lampman of the University of Wisconsin first proposed in the 1960s a related idea, a negative income tax (NIT). A half-century ago, there was no federal earned income tax credit (EITC), supplemental security income (SSI), child credit, Head Start, special education, or Section 8 low income housing assistance. Congress was just enacting Medicaid, and national health care spending was less than a third of what it is today as a share of the economy. Supporters of UBI are not clear about what they’d do with these programs, or how they’d address pressures such as medical cost growth. Nor do they say how they’d deal with existing tax subsidies, such as the EITC, and the ways people are taxed indirectly as their eligibility for these benefits is phased out. By choosing the acronym NIT, Friedman and Lampman recognized that phasing out benefits as income rises is effectively a tax rate increase.

If they don’t replace current support programs, in whole or in part, supporters of UBI need to figure out how to pay for the new cash benefit. And critics, such as Bob Greenstein and Eduardo Porter, question whether we could afford such a program.

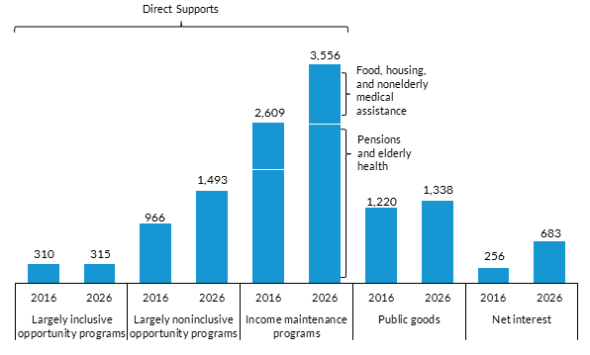

But in the medium term, a UBI could be funded simply by freezing the cost of current benefit programs and shifting scheduled increases to a cash program. Consider: Today, government at all levels provides about $35,000 annually in direct supports, including tax subsidies, per household. But that amount is due to increase by $10,000 to $15,000 by about 2026 and double within a few decades.

I’d prefer to shift larger shares of our direct support budget into promoting opportunity for work and saving, while promoting human and social capital. Such efforts would emphasize long-term earnings growth, wealth accumulation and upward mobility, whereas the UBI, with its focus on current consumption, would likely increase the inequality of market incomes by discouraging work.

Not that UBI supporters are wrong in stressing the inefficiency of existing programs. The type of efficiency they seek could be pursued in part by bundling programs together in a voucher that could be spent, say, on food, housing, or education—a design my Urban Institute colleague Bob Lerman and I called structured choice.

Despite the flaws of UBI, give its supporters some credit. They recognize both that the existing direct support system is quite flawed and we that do not have to be bound forever to a structure cobbled together over past decades in ways inattentive to current and future needs. There are just better reforms available than the UBI.

This post originally appeared on TaxVox.

Opportunity for All Isn’t Gonna Happen on This Path

Posted: May 17, 2016 Filed under: Columns, Income and Wealth, Taxes and Budget 1 Comment »Over the past 30 or 35 years, income and government spending per household have both about doubled, but working- and middle-class Americans have seen much less improvement in their earnings, wealth, education, and skills than they did in earlier decades. The international economy and the concentration of power within the top 1 percent are major factors, but it’s hard to believe that we can’t do a lot better with the $60,000 in federal and state spending and tax subsidies we spend annually per household, or the $2 million in health, retirement, education, and other direct supports scheduled for each child born today. My recent study finds that the US budget is moving increasingly away from promoting opportunity for all.

At the same time, Hillary Clinton, Donald Trump, and almost everyone running for office ascribe to the notion of America as a land of opportunity while telling supporters they are being denied the opportunities owed them. But it takes more than rhetoric to climb out of our current political pit.

In the study I draw three major conclusions:

- First, the few programs that attempt to promote opportunity, such as work incentives and education, are scheduled to take a smaller share of available federal government resources. There is one major exception: large tax subsidies for housing and for employee benefits like retirement accounts continue to expand. However, by largely excluding low- to middle-income households, those programs show how today’s programs largely fail to promote opportunity for all. That is, they are not inclusive opportunity programs. Figure 1 summarizes these results.

- Second, if we wish to promote opportunity for all, we must carefully discern the outcomes pursued and judiciously measure how well programs achieve those outcomes. “Opportunity for all,” if left amorphous, lacks any prescriptive power, leads to claims that anything the government does or stops doing can promote opportunity, and, as long as the intended outcomes are unspecified, prevents assessing program performance. I suggest that opportunity for all is not simply an equity objective: it pursues outcomes centered on growth over time in earnings, employment, human and social capital, and wealth while it emphasizes inclusion, especially of low- and middle-income households. And I suggest that we can and should measure most programs by their performance on that opportunity standard, even if the primary standard by which they are judged—such as retirement, food security, or even defense—seems initially removed from that opportunity focus.

- Third, there’s tremendous budgetary potential for promoting opportunity whether the government increases or decreases relative to the economy. Realizing this potential doesn’t require moving backward on other fronts but shifting tracks, as from north to northeast, to also move forward on the opportunity front. The trick is to channel a larger share of the additional revenues provided by economic growth toward an opportunity agenda. Ten years from now annual federal spending and tax subsidies are scheduled to increase some $2 trillion (or roughly $15,000 per household), but essentially none of that growth goes to opportunity-for-all programs. Children receive almost nothing a decade hence, while interest on the debt rises significantly because we are unwilling to collect enough taxes to pay our bills as we go along.

When you look at these numbers, it seems clear that reorienting budget priorities could help provide opportunity in ways likely to promote equality in earnings and wealth. What is also clear, however, is that small ball is not going to get the job done when so much in the budget is moving in the direction of deform, not reform.

Figure 1

Total Outlays and Tax Expenditures for Major Budget Categories under Current Law

Billions of 2016 dollars

Source: Author’s tabulations of Congressional Budget Office data.

Notes: Public goods include such items as defense, infrastructure, and research and development that benefit the population broadly. Direct supports are programs and transfers that directly benefit households and communities, such as health care and education. Within direct supports, income maintenance programs such as Social Security, Medicare, and SNAP (formerly food stamps) protect a certain level of income and consumption, while opportunity programs aim to increase private earnings, wealth, and human capital over time. Largely inclusive opportunity programs benefit low- and middle-income groups, while noninclusive opportunity programs largely exclude them or provide them with fewer supports than upper-income groups.

EITC Expansion Backed By Obama and Ryan Could Penalize Marriage For Many Low-Income Workers

Posted: April 5, 2016 Filed under: Columns, Income and Wealth, Taxes and Budget 3 Comments »President Barack Obama and Speaker Paul Ryan have proposed similar expansions of the earned income tax credit (EITC) for low-income workers without children. Their goal is laudable: to provide some modest additional income support for low-income workers currently excluded from the EITC. But as designed, their proposals would penalize many low-income workers who choose to marry or are married. Taking that step would not only provide a disincentive to marriage, it would be unfair to many married couples and erode support for the credit itself and for wage subsidies more broadly.

Fortunately, they can fix this flawed design by splitting credits for low-wage workers and benefits for children. Before I explain how, here is a bit of background.

The EITC, enacted first in 1975 under President Gerald Ford, has been expanded under every succeeding president and has broad bipartisan support. As cash welfare programs like Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) and its replacement, Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF), have shrunk as a share of both the economy and the budget, the EITC has become a bedrock of the nation’s social welfare structure and the largest government cash support for those neither retired nor disabled.

About 97 percent of EITC benefits, however, go to households with children, particularly single parent families. The very small sliver going to single individuals through the so-called “childless worker” credit is limited by a maximum of less than $600 and is completely phased out at less than $15,000 of income, or less than what would be earned at a full-time minimum wage job. By contrast, the EITC can provide close to $6,300 in 2016 for a single parent with three children and is available to families with up to $48,000 of income ($53,000 in the case of married couples).

Obama and Ryan would double the childless worker credit and increase the income levels at which it phases out. A similar though higher level of credit was provided by the Paycheck Plus Project in New York City, which offers some individuals up to $2,000 and even allows a modest credit for those making up to $30,000.

There’s a glitch in these proposals, however, and it’s a big one. For instance, one report suggests that Paycheck Plus provides “more generous support to all low-income workers.” But in reality it doesn’t. Many low-wage workers who marry into families not only lose their own childless worker credit, but also reduce the normal credit available to their partner with children.

Here’s one example of how they lose out. A childless male making $11,000 qualifies for a credit of $1,011 under the Obama-Ryan model in 2016. If he marries a spouse with two children making about $20,000 and getting a credit of $5,172, they would get only one credit of $4,018, a loss of $2,165 from the combined credits of $6,273 they had before marriage.

As a result, the credit Obama and Ryan both support would penalize many married couples, while encouraging low-income couples to delay marriage and household formation. Because these penalties would be quite transparent to millions of married couples filing their tax returns, they would likely erode support for the EITC in general.

There is an ongoing debate about how much a marriage penalty actually affects decisions to wed, but there is little doubt that avoiding marriage is THE tax shelter for low- and moderate-income individuals.

The problem can be fixed by separating credits for low-wage work and benefits for children. My Tax Policy Center colleague Elaine Maag and I have proposed this separation as a way to expand work supports for both groups largely left out now: the childless worker and low-wage workers who marry. As for the single head of household, her current credit would be replaced by two credits: one for households with children and an additional low wage worker credit based solely on earnings regardless of children. They’d phase in and out at roughly the same income levels and add up to roughly what she received under the old EITC.

Meanwhile, both the single person without children and the low-wage worker who marries into a family could get the new low-wage worker credit whether or not the family has children. Married couples with two low-wage workers would usually be better off, as now the addition of a worker to the household usually typically adds to rather than subtracts from total household credits received. Though we phase out the low-wage worker credit for those married to high wage workers, these are families for whom any EITC marriage penalty would be a smaller share of total income and who, at their income levels, largely benefit from marriage bonuses from other parts of the income tax rate structure.

The structure of any EITC is hard to summarize in a short column. The main takeaway is that the President and the Speaker could fix their proposals to do what they say they want—cover those low-wage workers now largely left out. And they could do it without penalizing those who vow commitment to their partners and their children.

This post originally appeared on TaxVox and UrbanWire.

Recent Social Security reform doesn’t fix unfair spousal benefits

Posted: November 5, 2015 Filed under: Aging, Columns, Income and Wealth 1 Comment »The budget compromise forged by Congress and the Obama administration at the end of last month makes two fundamental changes in Social Security. First, it denies a worker the opportunity to take a spousal benefit and simultaneously delay his or her own worker benefit. Second, it stops the “file and suspend” technique, where a worker files for retirement benefits then suspends them in order to generate a spousal benefit.

Unfortunately, neither of these changes gets to the root issue: that spousal and survivor benefits are unfair, although the reform redefines who wins and who loses. Social Security spousal and survivor benefits are so peculiarly designed that they would be judged illegal and discriminatory if private pension or retirement plans tried to implement them. They violate the simple notion of equal justice under the law. And as far as the benefits are meant to adequately support spouses and dependents in retirement, they are badly and regressively targeted.

As designed, spousal and survivor benefits are “free” add-ons: a worker pays no additional taxes for them. Imagine you and I earn the same salary and have the same life expectancy, but I have a non-working spouse and you are unmarried. We pay the same Social Security taxes, but while I am alive and retired, my family’s annual benefits will be 50 percent higher than yours because of my non-working spouse’s benefits. If I die first, she’ll get years of my full worker benefit as survivor benefits.

Today, spousal and survivor benefits are often worth hundreds of thousands of dollars for the non-working spouse. If both spouses work, on the other hand, the add-on is reduced by any benefit the second worker earns in his or her own right.

An historical artifact, spousal and survivor benefits were based on the notion that the stereotypical woman staying home and taking care of children needed additional support. That stereotype was never very accurate. And today a much larger share of the population, including those with children, is single or divorced. Plus, many people have been married more than once, and most married couples have two earners who pay Social Security taxes.

Where does the money for spousal and survivor benefits come from? In the private sector, a worker pays for survivor or spousal benefits by taking an actuarially fair reduction in his or her own benefit. In the Social Security system, single individuals and married couples with roughly equal earnings pay the most:

- Single people and individuals who have not been married for 10 years to any one person pay for spousal and survivor benefits, but don’t get them. This group includes many single heads of households raising children.

- Couples with roughly equal earnings usually gain little or nothing from spousal and survivor benefits. Their worker benefit is higher than any spousal benefit, and their survivor benefit is roughly the same as their worker benefit.

The vast majority of couples with unequal earnings fall between the big winners and big losers.

Such a system causes innumerable inequities:

- A poor or middle-income single head of household raising children will pay tens of thousands of dollars more in taxes and often receive tens of thousands of dollars fewer in benefits than a high-income spouse who doesn’t work, doesn’t pay taxes and doesn’t raise children.

- A one-worker couple earning $80,000 annually gets tens of thousands of dollars more in expected benefits than a two-worker couple with each spouse earning $40,000, even though the two-worker couple pays the same amount of taxes and typically has higher work expenses.

- A person divorcing after nine years and 11 months of marriage gets no spousal or survivor benefits, while one divorcing at 10 years and one month gets the same full benefit as one divorcing after 40 years.

- In many European countries that created benefit systems around the same stereotypical stay-at-home woman, the spousal benefits are more equal among classes. In the United States, spouses who marry the richest workers get the most.

- One worker can generate multiple spousal and survivor benefits through several marriages, yet not pay a dime extra.

- Because of the lack of fair actuarial adjustment by age, a man with a much younger wife will receive much higher family benefits than one with a wife roughly the same age as him.

When Social Security reform eliminated the earnings test in 2000 and provided a delayed retirement credit after the normal retirement age, some couples figured out ways to get some extra spousal benefits (and sometimes child benefits) for a few years. After the normal retirement age (today, age 66), they weren’t “deemed” to apply for worker and spousal benefits at the same time, allowing them to build up retirement credits even while receiving spousal benefits. Other couples, through “file and suspend,” got spousal benefits for a few years while neither spouse received worker benefits.

These games were played by a select few, although the numbers were increasing. Social Security personnel almost never alerted people to these opportunities and often led them to make disadvantageous choices. Over the years, I’ve met many highly educated people who are totally surprised by this structure. Larry Kotlikoff, in particular, has formally provided advice through multiple venues.

So is tightening the screws on one leak among many fair? It penalizes both those who already have unfairly high benefits and those who get less than a fair share. It reduces the reward for game playing, but like all transitions, it penalizes those who laid out retirement plans based on this game being available. It cuts back only modestly and haphazardly on the long-term deficit. As for the single parents raising children — perhaps the most sympathetic group in this whole affair — they got no free spousal and survivor benefits before, and they get none after.

The right way to reform this part of Social Security would be to first design spousal and survivor benefits in an actuarially fair way. Then, we need better target any additional redistributions on those with lower incomes or higher needs in retirement, through minimum benefits and other adjustments that would apply to all workers, whether single or married, not just to spouses and survivors.

As long as we keep reforming Social Security ad hoc, we can expect these benefit inequities to continue. I fear that the much larger reform required to restore some long-term sustainability to the system will simply consolidate a bunch of ad hoc reforms and maintain these inequities for generations.

This column originally appeared on PBS Newshour’s Making Sen$e.