Challenges & Opportunities for Charities after the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act

Posted: May 21, 2018 Filed under: Nonprofits and Philanthropy, Taxes and Budget Comments Off on Challenges & Opportunities for Charities after the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs ActEugene Steuerle, Richard Fisher Chair at the Urban Institute and co-founder of the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center gave this presentation at the ABA Tax Meetings Exempt Organizations Committee luncheon in May 2018. A full transcript is available at taxpolicycenter.org.

“A pessimist sees the difficulty in every opportunity; an optimist sees the opportunity in every difficulty.”

I’d like to refine this idea, probably incorrectly attributed to Winston Churchill, with the wisdom of my teachers, by distinguishing among luck, serendipity, and misfortune. To me, luck—good or bad— results from random factors beyond our control. Serendipity reflects the good things more likely to happen when we put ourselves along a path with a higher-than-average probability of success, while misfortune happens, often unnecessarily, when we bet against a house that has stacked the odds in its favor.

I realize that the lexicographers may not fully agree with my definitions.

Chauncey M. Depew told the story that Noah’s wife one day was caught kissing the cook.

“‘Noah,’ she exclaimed, ‘I’m surprised!’

“‘Madam,’ he replied, ‘you have not studied carefully our glorious language. It is I who am surprised. You are astounded.’”

Are charities on a serendipitous path, where a virtuous cycle of improvement is more likely, or a path with greater odds of a vicious cycle of misfortune? I suggest that the treatment of charities in last year’s tax reform may reflect a path if not misfortunate at least less serendipitous than possible.

In any case, I want to spend most of this talk discussing why the current tax law is unsustainable and sets in motion forces for further reform. I then set out a bold but difficult agenda worth pursuing as we venture down that still-to-be-determined path.

READ MORE AT TAXPOLICYCENTER.ORG

How Both Public Tax Reform and Private Sector Initiatives Can Strengthen Charities

Posted: April 27, 2017 Filed under: Columns, Nonprofits and Philanthropy, Taxes and Budget 2 Comments »This post originally appeared in TaxVox.

In the March and April 2017 print editions of the Chronicle of Philanthropy, I proposed both a public and a private sector initiative for strengthening charities. These included improved tax policies as well as steps charities could take independently of any legislation. These initiatives aim to increase charitable giving of income, wealth, and time.

My organizing principle was simple: First, make tax subsidies more effective and efficient. Second, improve the way charities market themselves. Neither Congress nor the charitable sector has ever approached either task in a comprehensive way. The articles are here and here, with permission of the Chronicle.

Here, briefly, are my suggestions:

What government can do:

- Allow all taxpayers—even current non-itemizers—to claim a deduction for contributions above some minimum amount.

- Extend the deduction to gifts made by April 15 or filing of one’s tax return—similar to the extended contribution date for Individual Retirement Account contributions– rather than December 31 of the previous calendar year.

- Create a better donation-reporting system to IRS to reduce tax non-compliance, with a reward of an extra deduction for those donations; the improved tax compliance should more than pay for the extra reward.

- Make it easier for individuals to make donations from their IRA accounts.

- Reduce and simplify the excise tax on foundations.

- Encourage charitable bequests, especially if the estate tax is cut or repealed.

What charities can do, independently from government:

- Create a national campaign to promote giving, such as:

- Tell simple but powerful human-interest stories extolling generous people.

- Help donors identify worthy programs by promoting access to useful sources of information on each charity.

- Encourage people to give to charity when they settle disputes.

- Help people understand better their potential to give out of wealth, not just income, and to leave lasting legacies:

- Run endowment campaigns.

- Encourage wealth advisers to promote charitable giving.

Today charities feel under siege. They fear they are about to lose direct government support if Congress cuts domestic spending that funds the specific programs they run. And they worry that lawmakers will trim tax benefits for charitable giving by individuals and firms. Their concerns are legitimate but, in truth, over the many decades I have worked with charities on public policy issues, their advocacy has nearly always felt defensive.

Charities can easily become collateral damage from policies that are not aimed directly at them. Congress won’t decide broad issues such as size of government, tax rates, limits on tax incentives, or the share of revenues that should come from income taxes (the only tax where there is a charitable deduction) solely or primarily based on their effect on the charitable sector.

Thus charities must think longer-term as the nation is struggles to define a modern set of public policies and societal goals relevant to 21st century needs and opportunities. My suggestions are intended to extend well beyond any current political battle, no matter which party controls government at any point. Their goal is to strengthen the charitable sector, by improving both government incentives and the outreach and self-examination by non-profits themselves.

Fighting to maintain the status quo is not a strategic option. Nor should every charity expect to come out unscathed in this rapidly changing environment. But the US is facing important choices as it decides the direction and size of government in the Trump era. That debate ought to include a broad look at charities in this new environment and whether that includes strengthening, though reforming, the role of charities in American life.

Both Clinton and Trump would reduce tax incentives for charitable giving

Posted: November 7, 2016 Filed under: Nonprofits and Philanthropy 8 Comments »By: Joseph Rosenberg, C. Eugene Steuerle, Chenxi Lu, and Philip Stallworth. This post originally appeared on TaxVox.

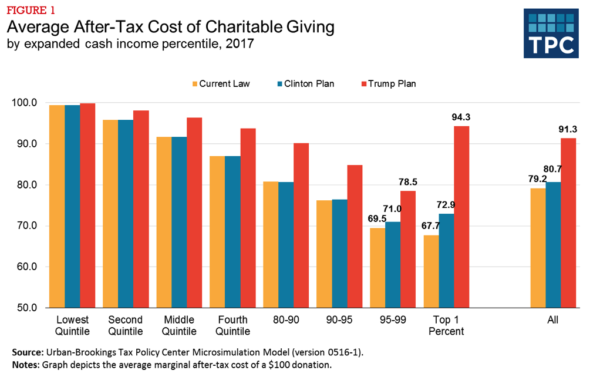

Both Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump have proposed income* tax changes that would result in less charitable giving. While the effects are indirect, the Tax Policy Center estimates that Trump’s plan would reduce individual giving by 4.5 percent to 9 percent, or between $13.5 billion and $26.1 billion in 2017, while Clinton’s plan would reduce giving by between 2 percent and 4 percent, or $6 billion to $11.7 billion.

The actual reduction in charitable gifts would depend mainly upon how responsive givers would be to smaller tax incentives. However, higher-income taxpayers would be affected the most. Lower-income households would not likely reduce giving since most do not itemize deductions today and would not under either the Trump or Clinton plans.

Figure 1 summarizes the increase in the cost (reduction in incentive) of giving under the two plans. The Clinton plan only affects the cost of giving for those in the top 5 percent, while Trump’s plan raises the cost of giving for those at all income levels.

Start with Trump, who would reduce the tax benefits of charitable giving in three ways:

First, by reducing marginal tax rates he’d increase the after-tax cost of charitable giving. If you give away $100, you don’t pay tax on that $100 of income, so the after-tax cost of the donation for someone in today’s 39.6 percent top tax bracket is only about $60—the $100 gift minus $39.60 in tax savings. But by reducing the top rate to 33 percent, Trump would raise the after-tax cost of that $100 gift to $67.

Second, by raising the standard deduction to $15,000 ($30,000 for couples), Trump would sharply reduce the number of taxpayers who itemize. People who stop itemizing can no longer deduct their charitable contributions and thus lose the tax break. In 2017, 27 million of the 45 million who now itemize would opt for the standard deduction, a decline of 60 percent.

Finally, Trump would cap itemized deductions at $100,000 for singles and $200,000 for joint filers. IRS data indicate that in 2014 taxpayers with over $1 million in adjusted gross income (AGI) deducted an average of $165,000 for charitable contributions and another $260,000 for state and local taxes. Since the state and local tax deduction alone would exceed Trump’s proposed cap on itemized deduction, many high-income taxpayers would lose their tax incentive to give to charity.

While all these changes might discourage charitable giving, Trump’s generous tax cuts would also leave taxpayers more money to give to charity. This would particularly be true for very high income households: In 2017, tax cuts for people in the top 1 percent would average more than $200,000.

Clinton’s plan would do little to change the giving incentives of taxpayers for the bottom 95 percent of the income distribution. She’d slightly increase incentives for low- and middle-income taxpayers to give to charity by boosting their after-tax incomes.

In contrast to Trump, Clinton would significantly raise taxes on high-income households. She’d impose a 4 percent surcharge on adjusted gross income (AGI) in excess of $5 million, increase capital gains rates based on holding periods, create a minimum tax of 30 percent of AGI phasing in between $1 and $2 million of incomes, and put a 28 percent limit on the value of tax benefits from deductions other than the charitable deduction. On net these not only decrease after-tax incomes, but also lead some current itemizers to take the standard deduction and thereby lose the charitable deduction. The proposal with the largest effective on giving incentives is the 30 percent minimum tax (i.e., the “Buffett Rule”), which would reduce the incentive for affected taxpayers.

Overall both candidates would reduce the tax incentives for giving to charity, probably not what either really intended.

*This analysis only includes changes in the federal income tax. Both Clinton and Trump have also proposed significant changes to the estate tax that would impact incentives to donate to charity and leave charitable bequests. Clinton’s proposal to lower the estate tax threshold and increase estate tax rates would increase giving incentives, while Trump’s proposal to eliminate the estate tax would reduce them.

The Zuckerberg Charitable Pledge and Giving from One’s Wealth

Posted: January 11, 2016 Filed under: Columns, Nonprofits and Philanthropy, Taxes and Budget 2 Comments »Mark Zuckerberg and his wife, Priscilla Chan, recently pledged to donate 99 percent of their Facebook shares to charitable purposes over their lifetimes. They are doing it through the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, which uses a limited liability corporate structure.

Why not give to an IRS-approved charity, or a foundation created by Zuckerberg and Chan, instead? Two reasons leap to my mind, both shaped by nonprofit law. The first, which I fail to see in most commentary to date, is that generous lifetime giving by the wealthy can’t get much of a charitable deduction no matter how structured. Second, the Zuckerberg-Chan pledge falls into a class of efforts sometimes labeled “fourth sector” initiatives, which give much greater flexibility for how the money is used, including combining charitable and business purposes and lobbying for a favored cause—essentially what private individuals can but pure charities cannot do.

Economic Income, Realized Income, and the Charitable Deduction

In studies examining the behavior of those with significant wealth, other researchers and I show how little income they tend to realize, often 3 percent or less of the value of that wealth. That doesn’t mean the investors have earned such low rates of return. In fact, many like Mark Zuckerberg became millionaires or billionaires because they got very high returns. Most of their money, however, tends to be in stock or a closely-held business and, especially for those with only a few million dollars in total wealth, residences and vacation homes. As long as the wealthy don’t sell those assets, they won’t “realize” for tax or other accounting purposes the true economic returns or gains they achieve. And those gains can be substantially more than 3 percent: from 1926 to 2014, including during the Great Depression and Great Recession, stocks produced an average annual return of about 10 percent before inflation.

Related research examining the charitable activities of such wealthy individuals shows that most delay a huge portion of their giving until death. That is, they give from the wealth of their estates, not the income of their lifetimes. Why? Because tax law provides very little incentive to give huge donations to charity during a lifetime. Let’s suppose that Mark Zuckerberg and Priscilla Chan normally realize as income 2 percent of their estimated $45 billion wealth, or $900 million, this year. The charitable deduction is limited to 50 percent of yearly income, which in Zuckerberg and Chan’s case is $450 million; it’s only 30 percent ($270 million) if they want to give to foundation. Thus, if Zuckerberg and Chan give away more than 1 percent of their wealth each year, they run out of allowable charitable deductions. If in an average year they earn 10 percent on their wealth and give away only 1 percent, they are still accumulating much faster than they are giving it away, unless they consume billions annually.

Running out of charitable deductions doesn’t mean that the wealthy gain nothing from giving away money directly to charities earlier in life. Once assets are transferred to a charity, the donors don’t have to pay taxes on the income earned from those assets. But donors such as Zuckerberg and Chan would achieve only modest tax savings from early gifts to charity as long as their taxable income from the alternative remains a small percentage of their wealth. What also might be in play here, and I don’t fully know, is that the charitable side of the Chan Zuckerberg initiative will yield enough losses, transfers, and sales to needy individuals at below-market cost to offset any taxable income otherwise earned on the business side, so it can effectively avoid income tax just as well as an outright charity.

For Benefit Corporations and the Fourth Sector

So limits on the advantages of a charitable deduction provide a significant impetus for wealthy individuals to pledge money for charitable purposes without necessarily giving it to a charity. Donors may also think the flexibility they gain is substantial relative to any potentially modest tax costs. Giving to charity later is always an option, thus avoiding estate tax; meanwhile, other options haven’t been foreclosed.

Among the additional options at play is combining nonprofit and business activity. Among the many efforts of this type that get complicated in a pure charity setting are raising private equity; sharing real estate investment returns with low-income residents; running a business centered around training its workers and building up their equity rather than making profits for investors; investing in new drug research and pledging that the public, not investors, will garner any potential monopoly returns from some successful patent; or investing in green energy by granting some risk protection to private capital partners; and garnering research and development tax credits.

Some states have tried to create special rules applicable to certain “for-benefit corporations” that allow shareholders and charities to share returns. But, for the most part, the walls surrounding charitable money can’t be torn down. Federal and state tax and other nonprofit laws protect money that now essentially belongs to the public (with the charity as fiduciary), not to the donors.

If donors aren’t worried about getting a charitable deduction up front anyway, as is likely the case for Zuckerberg and Chan, the easiest route is to create a potentially profit-making limited-liability business. Meanwhile, donors can engage in all sorts of ventures without having their lawyers shouting “Stop” to each new creative idea because it might violate some charitable law. At the same time, Zuckerberg and Chan need a new entity since they can’t pursue their charitable pursuits directly through Facebook without soon running into problems meeting that corporation’s obligations to other shareholders.

If Zuckerberg and Chan decide that they want to lobby government, they also can avoid any limitation imposed on foundations or other charities.

These types of private initiatives, sometimes labeled as a Fourth Sector, push society in new, exciting, and yet-to-be-determined directions. As I’ve discovered when I raise money for charity, people will often consider giving away much more when asked to think about giving out of their wealth, not just their realized income. Fundraisers, take note: I don’t think we’ve even begun to tap this way of encouraging giving. Also, people often see new possibilities for enhancing charitable purposes when not confining themselves within the walls surrounding a typical charity, with entrepreneurs and venture capitalists often especially excited by the new adventure. Zuckerberg and Chan are merely two of the richer faces giving new attention to these broader movements.

An April 15 Deadline for Charitable Giving Would Be a Boon to Nonprofits

Posted: December 16, 2014 Filed under: Columns, Nonprofits and Philanthropy, Taxes and Budget Leave a comment »Many years ago, I began to suggest that taxpayers should have the opportunity to give to charity all the way until April 15 and then take a deduction against their previous year’s taxable income.

Now the idea is getting attention from lawmakers—but it needs the support of charities to make possible the increase in charitable giving it would foster.

In previous years, Congress approved a post-December adjustment to stimulate certain kinds of behavior: Taxpayers who add to individual retirement accounts have been offered a similar option since the mid-1970s, and Congress has occasionally extended the charitable-giving deadline to April 15 for disaster relief, as in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina.

A great deal of evidence suggests that simply changing the charitable-deduction deadline could increase giving significantly.

Nonprofits like the Jewish Federations of North America support the option, but some other charities have expressed concern about whether it would harm end-of-year appeals.

I would suggest that these charities avoid thinking of charitable giving as a fixed amount—what I call the “clump of charity” thesis.

All the research, plus some real-life fundraising experience, suggests that the April 15 option would lead to an overall increase in the sums Americans give annually.

Just for a minute, however, let’s suppose that the clump-of-charity thesis is right and that the amount of charitable giving nationwide is the same every year. If that’s the case, then it’s unwise to add this new wrinkle to the tax system. But consider the corollaries: If giving is immune to incentives or circumstances, then both the charitable deduction and fundraising more broadly are superfluous, if not wasteful.

I doubt that most fundraisers believe the clump-of-charity thesis, so the real question is whether an April option would increase giving. Here are six pieces of evidence suggesting it would be a wise policy:

Taxpayers tend to underestimate the incentive to give. Several scholarly papers, including by researchers associated with the Federal Reserve Board and the National Bureau of Economic Research, have examined how well taxpayers understand and respond to tax provisions.

It turns out that many taxpayers, particularly middle-class ones, possess only a limited idea of their marginal tax rate—that is, the rate of subsidy they would get for additional charitable gifts if they itemized. They tend to equate the marginal rate with the average rate of tax they pay on all income, not recognizing that tax law looks differently at the first dollar and the average dollar earned than at the last one.

For example, a taxpayer who earns $50,000 might owe $5,000, or 10 percent of income on average. So she might imagine at year’s end, without formally doing her taxes, that donating $100 more before April 15 would save her that average percentage, or just $10 in taxes. But if she prepared her taxes under an April 15 option, she would get a formal notice from her tax software or tax preparer telling her such a gift would save her $25 and cost just $75 out of pocket.

If people saw this information laid out clearly with a first draft of their tax return, they would quickly grasp the real benefits of an increase in giving.

Few people know their tax and income circumstances until they get that information in January and beyond. Many Americans reconcile their books when preparing their tax returns. At this time, they see whether they’ve met goals and what options they’ve passed up but should have considered. That’s why the April 15 proposal should appeal to organizations that are working to attract gifts of all sizes, not just those that get more modest contributions from the broad middle class.

Advertising works best when it is closely timed to the activity you want to promote. Marketers understand this: That is why grocery stores send flyers out near weekend shopping time, not months in advance.

There is absolutely no time like tax time, not even the end of the year, when people are so tuned into taxation after toting up their annual income and charitable gifts. What better time to promote an opportunity to them?

Charities would get tons of free marketing from influential players. Hundreds of thousands of tax preparers and tax-software designers would promote the idea of charitable giving to their clients. Tax software already walks people through ways to reduce their taxes, and my discussions with people who deal with the interaction between technology and fundraising indicate that people preparing their tax returns could easily be encouraged to make a gift with just a few clicks of a mouse while filling out their returns.

Many trained tax preparers, in turn, would give special attention to the April 15 option for reducing taxes. They want to make clients happy, and they, too, want to improve their communities and the nation.

The April 15 option would be an even better deal for the federal treasury than the basic charitable deduction.

While the charitable deduction on average increases giving by 50 cents to $1 or a bit more for every dollar of revenue lost to the government, the April 15 option would provide $3 to $5 on average to charity for every dollar of revenue loss.

Why? Much of the existing deduction subsidizes giving that would occur anyway, but the additional cost with the April 15 idea applies only to added giving. For a taxpayer in a 25-percent marginal tax bracket, for instance, each additional $100 of giving costs the Treasury just $25.

People don’t like paying taxes. Alex Rees-Jones, an assistant professor at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School, has found that taxpayers seek to minimize the amount they owe when they file.

The April 15 option would allow them to pay less to Uncle Sam when they haven’t withheld enough money over the year, and it would be a good way to use some of their refund when they have. They could also avoid penalties at times by simply giving more to charity.

To be sure, people who worry about the April 15 idea do have a legitimate concern: While giving over all would almost assuredly go up, some people would simply change when they give.

Still, while some people might delay one year’s end-of-year giving until the first months of the following year, others might accelerate each year’s end-of-year giving to the beginning of the same year.

This adjustment, I believe, is a small price to pay for the gain to charities over all. And charities can maximize the benefits by promoting giving both at the emotional time when people are thinking about helping others during the holidays and then again at tax time when people are focusing on taxes and how tax incentives help them stretch their own finances to aid those in need.

The debate over the April 15 option reminds me of when I served as a cofounder of a community foundation in Alexandria, Va. Initially, a few charities expressed anxiety about competition, but once they saw how the foundation’s activities raised money for them and helped expand their management capacity, any fear turned to broad-based support.

The April 15 option deserves the full advocacy of all nonprofits. It would be among the most cost-efficient ways possible to increase giving.

At a time when we depend so heavily on nonprofits, that’s exactly what we need.

This post originally appeared in The Chronicle of Philanthropy.

Dave Camp’s Tax Reform Could Kill Community Foundations

Posted: April 24, 2014 Filed under: Columns, Nonprofits and Philanthropy, Taxes and Budget Leave a comment »House Ways and Means Committee Chair Dave Camp deserves credit for proposing a tax reform that takes on many special interests, something too few other elected officials are willing to do. But one provision mistakenly threatens the survival of most community foundations without improving the tax system or strengthening the charitable community.

The proposal would effectively eliminate most donor advised funds (DAFs), the major source of revenues to community foundations, so they could no longer provide long-term support for local and regional charitable activities. Instead, those funds would need to pay out all their assets over a period of five years.

DAFs support community foundations in two ways. First, donors pay about one percent of asset value to the foundation for sponsoring the fund. Second, community foundations distribute donor gifts to many local charities. By simplifying giving and reducing costs, they make it possible for people who are not wealthy to endow charitable activities.

Requiring a community foundation to pay out all its assets over five years is equivalent to telling the Ford Foundation that it, too, must pay out all of its endowment over a short period of time. But the draft bill only targets those with limited funds, while it leaves the really big guys like Ford alone.

Usually, I analyze tax policy as a disinterested observer. But as chair of a community foundation called ACT for Alexandria, I have a personal interest in this issue.

So let me tell you how this proposal would lead to the demise of many of our activities and, likely, the community foundation itself.

Each year we engage in a one-day fundraising effort for the charities of Alexandria, VA, a city of about 145,000 across the Potomac River from Washington, DC. This year we raised over $1 million for 121 local charities, and many contributions to support the effort itself, not just the charitable contributions themselves, came from our donor advised funds.

The fees we earned from the funds supported our program to train local charities on how to better use social media and do online fundraising. No one else in the community does this coordination and training.

In addition, several of our donors create DAFs, often small, to engage their families in philanthropic efforts. By doing so, they encourage a new generation to make charitable giving part of their lifestyles.

DAFs give donors flexibility to vary their gifts as circumstances change. For instance, one of our funds provides long-term support for schools in Afghanistan through U.S.-based charities, but there is no guarantee that any particular Afghanistan project would be strong enough to merit a direct permanent endowment. Other funds support a long-term examination of early childhood education opportunities in Alexandria, a project likely to change as needs change. DAFs or equivalent funds also allow “giving circles” that combine small gifts to assist an activity without having to create a new charity every time.

Without these funds, we likely would be unable to support a grant program for capacity building and training of local nonprofit leaders.

I doubt seriously that Chairman Camp’s staff saw fully how they would wipe out most community foundations and confine endowment giving only to the rich. By making it more complicated and expensive to engage in such activity, they would move almost all endowment decision-making to elite, often established institutions where the average citizen has little or no voice and where the operational expenses are greater.

Why are critics of DAFs so worried about someone having a say over an annual grant of $5,000 out of an endowment but not when the President of Harvard decides over time how to spend billions of dollars out of the income from an endowment?

There are legitimate concerns over how such donor advised funds should be regulated. It may even be possible to design a proposal for a minimum annual payout, though, if badly designed, such a limitation could curb the ability of some people to build up assets to make a major gift to try to achieve some large charitable purpose.

The very small literature I have seen arguing for this type of proposal entangles DAFs and community foundations with separable issues. For instance, one can argue about the extent to which givers to charity should be allowed special capital gains treatment. But those discussions go well beyond DAFs, and removing DAFs as a source of more endowed funds hardly targets the perceived problem.

Still, I also understand why tax staff and policymakers sometimes see charities as just another special interest. The charitable sector needs to go beyond its “we’re all good, leave us alone” mantra, and address real problems as they arise.

There are ways for Congress to reform the tax laws that would raise revenues and strengthen the charitable sector. But this DAF proposal would wipe out most community foundations, increase administrative costs, and raise nothing or almost nothing for Treasury.

This post originally appeared on TaxVox. An earlier version of this column stated that a fund-raising effort by ACT for Alexandria supported over 200 charities; the corrected number is 121 charities

What Do Mark Mazur, Lois Lerner, and J. Russell George Have in Common?

Posted: July 15, 2013 Filed under: Columns, Nonprofits and Philanthropy, Taxes and Budget 2 Comments »Until recently, few Americans knew the names of these three Treasury officials, long-time public servants whose talent and many years of hard work elevated them to prestigious government positions. But many now recognize, if not their names, the issues with which they have been intimately associated. Each has moved into the spotlight recently after putting out a statement, report, or blog dealing with a very controversial aspect of tax administration: employer mandates under the new health care reform law, or Obamacare, in the first case; and tax exemption for social welfare organizations with such labels as “tea party” or “progressive” in the last two.

What Mazur, Lerner, and George also hold in common is the forced assumption of greater responsibility than is warranted, as elected officials and their top appointees—those who wrote or failed to fix the laws in the first place—scramble to secure a position of innocence and fault-finding in the blame game known as Washington, DC.

Mazur is the Assistant Secretary of the Treasury who first revealed in a blog posting the delayed implementation of one important feature of Obamacare, the mandate on larger employers to pay a penalty if they don’t offer health insurance to their full-time employees. Lerner is the IRS official, now threatened with criminal charges by politicians, who first noted that some of those under her had inappropriately targeted “tea party” and other groups for extra review when they applied for tax exemption as social welfare organizations. George is the Treasury Inspector General whose report on the IRS targeting of tea party groups is now being lambasted by Democrats for failing to note sufficiently that the IRS was simultaneously scrutinizing other applicants, such as progressives.

Should we focus so much attention on the talents of Mark Mazur in regulating, Lois Lerner in enforcing, or J. Russell George in inspecting? (I may be influenced by that fact that I know two of them, but I can assure you that many others would say that each is well above average in integrity, ability, and devotion to the public.) Or should we instead turn our attention to how the government turns inward when it functions poorly, the system creaks, and officials remain at an impasse to fix things everyone has long known are broken?

Every expert on nonprofit tax law will tell you that providing tax exemption for organizations operated for social welfare purposes (“exclusively” under Code section 501(c)(4), but “primarily” under the IRS’s more lenient regulations) does not mesh easily with organizations set up to engage in significant political activity. Also, delays in getting exemption have been an issue for years for nonprofits in general because of lack of IRS staffing, extensive abuse of the law, and the difficult-to-enforce boundary lines between exempt and nonexempt activities, the latter including political campaigning. And if there were an easy way to figure out which organizations really devote themselves to social welfare, why hasn’t the White House or any member of Congress come up with one? If things go amuck in some IRS Cincinnati office, wasn’t error built into the system a long time ago?

As for the health care reform law’s employer mandates, of course these were going to put extraordinary pressures on employers to hire part-time rather than full-time employees, on payroll and other reporting systems to devise ways to measure hours of work (however inaccurately), and on an understaffed IRS to somehow enforce the law’s requirements. If things go amuck, how much responsibility rests with Treasury and IRS versus a political system that can only vote thumbs up or thumbs down on Obamacare?

Rest assured, when new benefits are bestowed on citizens, messages spew forth from elected officials and their spokespersons in the White House and Congress. “Look what we have done for you,” they pronounce. Can you remember top White House and Treasury officials ever deferring preferentially to Mark Mazur to make one of these more politically appealing types of announcements?

When things unravel a bit, however, roles reverse. Elected officials and their top cadre quickly disassociate themselves from both the creation of the problem and their past failure to address it.

Wouldn’t it be a lot more honest to share responsibility for successes and failures, more helpful to reveal rather than hide the limits on tax administration, and more productive to spend more time on fixing than blaming? As long as every difficult issue threatens to become political high theatre, the Mazurs, Lerners, and Georges of long government service will be asked to play the role of clown or villain for scripts they can, at best, edit but not write.

Can Foundation Giving Relate Better to Society’s Needs Over Time?

Posted: June 18, 2013 Filed under: Economic Growth and Productivity, Income and Wealth, Nonprofits and Philanthropy, Shorts, Taxes and Budget 1 Comment »Charitable organizations form a vital part of America’s safety net. Ideally, foundations would be able to make greater payouts in hard economic times when needs are greatest. Unfortunately, the design of today’s excise tax on foundations undermines and in fact discourages such efficiency.

Under current law, private foundations are required to pay an excise tax on their net investment income. The tax rate is 2 percent, but it can be reduced to 1 percent if the foundation satisfies a minimum distribution requirement. The dual-rate structure and distribution requirements obviously introduce complexity. The stated purpose of the tax in legislative history—to finance IRS activities in monitoring the charitable sector—has never been fulfilled.

In the recent recession, the impact of the excise tax was especially pernicious, as it penalized those that maintained their level of grantmaking.

How? As Martin Sullivan and I first described in 1995, the excise tax penalizes spikes in giving; under the current formula, a temporarily higher payout results in a higher excise tax when payouts fall back to previous levels. A foundation that reduced its grantmaking during the last recession would not be subject to an increased excise tax because the amount the foundation paid out would be measured as a share of current net worth.

One proposal would replace the excise tax with a single-rate tax yielding the same amount of revenue. While a flat-rate tax would remove the disincentive to raise grantmaking in bad times, it still raises taxes for some foundations and not others.

A related law applying to foundations is the required payout rate, now set at 5 percentage points. Many experts have debated how high that rate should be. The current rate is believed to approximate the long-term real rate of return on a foundation’s balanced portfolio of assets. However, if foundations follow a strict rule of paying out the minimum 5 percent every year, they, too, will be operating procyclically, paying out more in good times when stock markets are high and less in bad times.

If we wish foundations to operate more countercyclically—to pay out more when needs are greater—we need to address both the excise tax and the natural tendency, reinforced by a minimum payout requirement, to make grants and payouts as a fixed percentage of each year’s net worth.