Addressing income inequality first requires knowing what we’re measuring

Posted: February 18, 2015 Filed under: Columns, Economic Growth and Productivity, Income and Wealth, Taxes and Budget 1 Comment »Politicians, researchers, and the media have given a good deal of attention recently to widening income inequality. Yet very few have paid attention to how—and how well—we measure income. Different measures of income show very different results on whether and how much inequality has risen. Without clarity, even honest and non-ideological public and private efforts to address inequality will fall short of their mark—and, in some cases, exacerbate inequality further.

How we typically measure income

Income measures tell different stories about opportunity and can be useful for different purposes. Some studies on income inequality measure income before government transfers and taxes—for instance, studies that compare workers’ earnings over time. Studies of the distribution of wealth or capital income, too, typically exclude any entitlement to government benefits. These “market” measures capture how much individuals have gained or lost in their returns from work and saving.

More comprehensive measures examine income after transfers and taxes. Transfers include Social Security, SNAP (formerly food stamps), cash welfare, and the earned income tax credit. Taxes include income and Social Security taxes. These measures best capture individuals’ net income and what living standards they can maintain, but not their financial independence or how much they are sharing directly in the rewards of the market.

Within both sets of measures (pre-tax, pre-transfer and post-tax, post-transfer), most studies still exclude a great deal. Health care often fails to be counted, even though increases in real health costs and benefits now take up about one-third of all per-capita income growth. Most of these health benefits come from government health plans (like Medicare and Medicaid) or employer-provided health insurance. Households pay directly for only a minor share of health costs, so they often don’t think about improved health care as a source of income growth.

How improving our definition of income—and using alternative measures—sharpens our view of income inequality

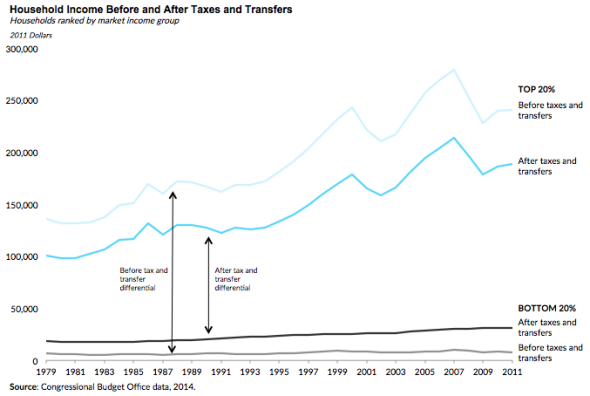

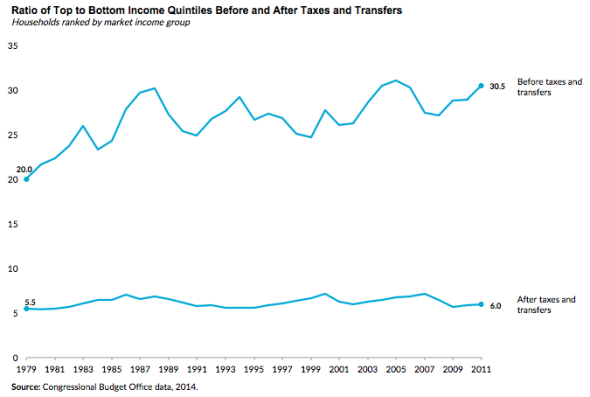

Starting with a more comprehensive measure of income, and then breaking out components, can improve our understanding of income inequality and its sources. As an example, let’s use some recent Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates, which provide perhaps the most comprehensive measure of household market incomes (consisting of labor, business, capital, and retirement income), then add the value of government transfers and subtract the value of federal taxes.

Between 1979 and 2011, the average market incomes—that is, incomes before taxes and transfers—of the richest 20 percent of the population (or the top income quintile) grew from 20 times to 30 times the incomes of the poorest 20 percent (the bottom income quintile).

When examining income after taxes and transfers, however, the relationship between the top and bottom income quintiles is more stable. It starts at a ratio of about 5.5:1 in 1979 and increases very slightly to 6:1 by 2011.

We find somewhat similar trends when comparing the fourth quintile with the second quintile. After taxes and transfers, income ratios don’t change much over this period, though the market-based measures of income show increased inequality. Of course, the very top 1 percent still has gained significantly; in 2011 it had nearly 33 times the income of the bottom 20 percent, compared with about 19 times in 1979.

What’s still missing

Even the CBO measures, however, are far from comprehensive. They exclude many benefits that are harder to measure or distribute, such as the returns from homeownership and the value of public goods like highways, parks, and fire protection. As Steve Rose points out, even more elusive are the broadly shared gains in living standards brought by improved technology and new inventions.

Why getting it right matters

Though defining income may seem like merely a technical exercise, it has huge consequences. Inequality has always been a political football: all sides tend to quote statistics that support their policy stances while ignoring the statistics refuting them. Yet if we want good policy, we’ve got to be open to how well any particular policy might improve income equality by one measure or make it worse by another, often at the same time. This is not a new story: bad or misleading information almost inevitably leads to bad policy.

This column first appeared on MetroTrends.

America’s Can-Do New Year’s Resolution

Posted: January 6, 2015 Filed under: Columns, Economic Growth and Productivity, Income and Wealth Leave a comment »How about a national new year’s resolution for 2015? Here’s my suggestion: let’s resolve to restore our can-do spirit, sense of destiny, and vision of frontiers as challenges rather than barriers. Let’s remember that fear and pessimism multiply the negative impact of bad events, whereas optimism reinforces positive outcomes. Think of Louis Howe, who added “the only thing we have to fear is fear itself” to Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s first inaugural address, or Henry David Thoreau, who wrote that “nothing is so much to be feared as fear.”

Now, seven years after the start of the Great Recession, it’s a good time to reflect on just how lucky we are as a nation and on the vast ocean of possibilities that lie before us. If we don’t see those possibilities, we’ve simply turned our back to them—and forgotten how America became America in the first place. In Dead Men Ruling, I attack viciously both the notion that we live in a time of austerity and the politics that sells pessimism as a way of clutching onto our piece of the national pie.

No one knows the future, of course. But the evidence points strongly toward the potential of a people whose can-do spirit helped it establish the first and now longest-lasting modern democracy, conquer frontiers of land and space alike, enhance freedom at home and abroad, and lead in the industrial, technological, and information revolutions.

Though income tracks only some of our general gains in well-being, we’re hardly poor. Our GDP per household is about $145,000, and real income per person is more than 75 percent higher than when Ronald Reagan was first elected president. We are richer than before the Great Recession. And, even projections of slower growth imply that average household income will rise by around $24,000 within roughly a decade.

We have available goods and services of which kings and queens of old could not have dreamt: not just the very visible gains in ways of communicating and entertaining ourselves, but fresh fruit and vegetables year round, life expectancies and health care far beyond those of our parents and grandparents, and continually improving automobiles, shelter, clothing, travel options, plumbing, and building architecture. And much more to come.

Of course, it’s part of our human condition to focus on the next problems, the ones we haven’t solved. Such striving provides the very basis for continued growth. Your hard labors, your dedication and sacrifices, and your everyday efforts to care for older and younger living generations may not make news. But they do make the world go around.

Our mistake comes from paying attention to those in politics, the media, or our own community who turn our mutual problems into excuses for personal attacks or a sense of helplessness rather than calls for further joint and individual efforts. We know the temptations: for the media, if it bleeds, it leads; for the politician, if it smells, it sells; for the business, if it deceives, it succeeds. But there’s no reason that either they or we need fall prey to such tricks.

If some current debates aren’t as enlightened as they might be, we can still sense progress from where they might have been a generation ago. We don’t debate whether cops should discriminate against different groups—an issue my brother-in-law confronted while working for the FBI in Little Rock, Arkansas in 1957—but instead how to pay proper respect to each person, civilian and cop alike. We don’t debate whether people should have enough food to eat but whether graduate students should collect food stamps. We don’t debate whether to help the disabled but how to extend efforts toward the mentally ill, the autistic, and those who are too old to be treated in school settings. We don’t debate whether to protect the old but whether our old age programs emphasize too much middle-age retirement rather than the needs of the old. When we engage these debates, whether on the same or different sides, most of us concentrate on how to do better, how much government efforts help or hinder progress, and how to shift our resources toward more effective or productive efforts.

In the end, the case for progress rests not on some wild-eyed dream but on the simple notion that we stand on the backs of those who went before us. Available knowledge expands. It doesn’t recede—even if at times we let our minds recede through laziness, prejudice, and fear of the new, or we reinforce political institutions that protect their power or status by blocking advancement.

That’s where we Americans are especially lucky. The can-do spirit, the entrepreneurial urge, and the freedom to try new things have been among the greatest strengths of our people, who continually find new paths forward and ever-broader vistas.

So my optimism is easy to explain: I trust in you. Happy New Year.

Economic Competition and the NCAA Basketball Tournaments

Posted: April 7, 2014 Filed under: Columns, Economic Growth and Productivity 5 Comments »I love the NCAA tourneys. I grew up in Louisville at a time when basketball was synonymous with Kentucky, Ohio, and Indiana. I give the NCAA and the networks credit for building up the excitement, tension, and attention in this national event. This year, my interest was especially piqued because five family alma maters (including mine) made it to the Sweet Sixteen of the men’s tourney: Dayton, Wisconsin, Louisville, Kentucky, and Virginia.

My undergraduate school, Dayton, was among the elite in college basketball in the 1950s—and, to some extent, the 1960s. Dayton fell in status over time because, at least relative to some other schools, it started stressing academics more and athletics less. These experiences color the lessons on economic competition, both positive and negative, that I draw from the tournaments each year.

When competition flourishes, it’s hard to establish a monopoly.

Okay, Harvard did make it to the men’s tourney this year, but credentials don’t go very far when your accomplishments determine whether you get ahead. This stands in contrast to the politics of academia. High school seniors focus intensely on college admissions because they correctly sense that future success depends not simply on what they learn than but where they can make connections to get onto a faster career track. If you’re an economist, for instance, your odds of a top job in either a Democratic or Republican administration multiply one-thousand-fold if you have a Harvard connection at some point in your education as opposed to, say, a University of Connecticut one. It’s tough finding a job teaching history almost anywhere if your PhD is not from a ranked university, no matter the brilliance of your work. The NCAA appeals to the common person, I think, because we identify with any field where anyone with enough talent and effort can succeed.

Create a level playing field (court), and you’d be amazed at the amount of upward mobility.

Many of my fellow social scientists despair of the lack of upward mobility in American society, with young black men especially singled out as left behind. Yet notice their success in basketball, where there’s pretty much a level playing field from the time of birth. If you can run circles around me on the court, I can’t rise above you by turning to Daddy’s friends or the connections available only in higher-income communities. (Then again, maybe I can succeed in athletics by convincing the Olympic Committee to adopt some new sport played by an elite few. How many kids in inner-city Detroit have access to $100,000 bobsleds or a “playground” for luges?)

Money still matters—a lot.

As the tourney goes on and my position in the office bracket pool falls lower, I start turning to my cynical side and some negative lessons. Though there’s close to true competition among athletes, schools still compete on more than talent. Large state schools have done quite well in recent decades with the move toward big-money sports and huge TV rewards, perhaps even more so in football than basketball because of the expense involved. Multimillion-dollar coaching salaries, extraordinary facilities, the latest in physical therapy, and multiple support staff to develop statistics or simply run around as lackeys—you name it, each of these can add to the probability of success. Given this world, I shouldn’t admit that I’m still thankful to former Wisconsin chancellor Donna Shalala for bringing big-time sports success back to Wisconsin; it’s not surprising that Miami hired her away after her stint in the Clinton administration.

Those who take maximum advantage of the letter of the law often do well.

Consider the new Kentucky style of “one and done”: recruiting players who never intend to study or complete more than a year of school once they become eligible for the NBA draft. It works. It’s easy to cast Kentucky coaches in the same light as those traders on Wall Street who gain by faster computerized trading or better access to soon-to-be public information. Or multinationals that shift their profits with the flip of a switch to some low-tax country. It may all be legal (or almost legal), but dodges like these don’t generate growth in a capitalist economy or additional value for watching sporting events. In many ways, the relative advantage for these winners comes mainly from avoiding having to compete under the same rules as everyone else.

The working stiff still gets shafted.

Everyone knows that there’s big money to be made in major college sports. One way to get rich is to leverage the work of others, then claim a large share of the total rewards from the enterprise for yourself. Perhaps the few college basketball players who make it to the NBA might claim that their college training was a good investment. For many other big-time college sports athletes, the reward can be a 50+ hour workweek at almost no pay and a loss of other educational opportunities (see Joe Nocera’s take on unionization of players as employees).

Suppose society is willing to pay $1 billion to be entertained by the NCAA tournament. The players can’t get paid, though they might get some very nice meals or plush accommodations, so much of the $1 billion is up for grabs by coaches, athletic department personnel, and others—some of whom walk away with huge rewards at their athletes’ expense. The NBA also gets a free training ground and media promotion of its future players.

To be fair, the school receives some of the profits, and it divides the funds among money-losing athletics or (god forbid) academics. Still, the working stiff doesn’t have much say in the matter one way or the other.

My new book, Dead Men Ruling, is now available to order.

Nelson Mandela and the Formation of a Nation

Posted: December 9, 2013 Filed under: Economic Growth and Productivity, Shorts 3 Comments »A few years ago I visited a history museum in an Eastern European nation that had recently abandoned communism. It was quite depressing. In one room I could read about oppression under ancient royalty, in the next oppression under Hitler, in the next oppression under communism. I became acutely aware of how lucky I was to live in a nation with a positive history and legend about its founding and development, and the related ability to triumph over evils, internal and external, ranging from slavery to fascism.

A person like Nelson Mandela takes his country onto a higher plane. He serves as a beacon and inspiration for new generations. When the South African government falters, as it will over time, Mandela’s legend will continually call the people back to a time when hope for progress drove the nation.

Any country’s story of itself evolves from the actions of its heroes and the mythology (in the most positive sense of that word) that surrounds them. In the United States, our teachers and textbooks teach our schoolchildren to try to emulate our Washingtons, Jeffersons, Lincolns, Roosevelts, and Kings. With their leadership, we—and our nation—seemed to move to a higher and better plane. We don’t have to count on our Millard Fillmores to inspire us, even if plenty of them still seem to be around.

I worry greatly about those countries without heroes to inspire their citizens. People in Russia or Egypt may come to tolerate a Putin or a Mubarak-like successor because many of them haven’t known anything better. Despite the formidable talent of the Chinese people, they still look back to a Mao rather than a Gandhi for thinking about what their nation can become—giving India, in my view, an extraordinary leg up for development in this still-young century. In a country with true national heroes, the citizens come to see themselves as part of an evolving and perfecting culture. Failures aren’t tolerated as the way of the world but seen and actively opposed as obstacles to progress.

In this way, Nelson Mandela lives on—and will do so for centuries to come.

Civil Rights and Economic Mobility

Posted: September 5, 2013 Filed under: Columns, Economic Growth and Productivity, Income and Wealth, Race, Ethnicity, and Gender 1 Comment »The 50th anniversary of “the March on Washington”—so famous and, in many ways, so successful that “the” is sufficient to define it—brought forth a gusto of stories about what had been achieved since then, including some very interesting blog posts by my colleagues. Several turned to data on the distribution of wealth, including some studies in which I participated, noting the lack of gains—especially in the past few decades—in the wealth and income of blacks and Hispanics relative to whites.

Those aggregate, raw figures on wealth and income act as a form of performance test on one aspect of government policy. They state rather emphatically that, whatever its merits, such policy was not sufficient to move the needle on wealth mobility across and among racial and other classes. Some simply draw the conclusion that we must redouble our efforts on programs that they have favored for a long time. Spend more on Medicare or Medicaid or cut tax rates or whatever. But what if that focus is wrong? What if the dominant liberal and conservative agendas over the past 50 years, at least when it came to social policy and taxes, never really had much to with mobility? What if the data compel us to adopt more dynamic, yet realistic, policies that put mobility and opportunity more at the forefront of policy in the 21st century?

Over these past few decades, liberal agendas have focused largely on the positive effects of ensuring that people had adequate income, food, health care, and so on—that is, consumption. Conservative agendas have focused largely on the negative effects of high income tax rates, particularly at the top of the income distribution. Often raising legitimate concerns about poverty or incentives, respectively, in many ways, each side has won its battle. Redistributive and other social welfare policies now dominate the $55,000 in federal, state and local spending, including tax subsidies, now spent on average per household, while tax rates at the top tend to be about half what they were from World War II to the early 1960s.

Relative to 50 years ago, fewer people are without food or food assistance, people can now retire on Social Security for many more years, health care has become far more life-sustaining, more people go to college, and, while economic growth hasn’t been great lately, we’re still about three times richer than we were. So the record isn’t all that bad, despite current travails. But, once again, those successes largely did not carry over to mobility among and across classes.

Here are just a few examples of how policies have given limited attention to mobility:

- Current welfare policy helps feed and house people, but it often discourages work by imposing very high costs on moderate-income households with children, as they can lose hundreds of dollars of benefits for each $1,000 they earn.

- Even while single parenthood remains a major source of poverty for many, that same welfare policy now penalizes—on the order of hundreds of billions of dollars—low-income couples with children who decide to get or remain married.

- Although investing in quality early childhood education appears to have a high payoff, the means testing of Head Start and other programs re-segregates our schools, with poorer kids often clustered together in classrooms separate from middle-class kids.

- Housing rental subsidies help people live in decent housing, but they also discourage home-buying and paying off a mortgage along the way, keeping lower-income families away from that classic and, for large segments of the population, most important mechanism for saving.

- Our retirement policies help most Americans live their later years in some comfort. But by encouraging early retirement, Social Security and other programs lead to an increased wealth gap among the elderly as richer classes retire later—hence, work and save longer—than poorer classes.

- Low tax rates may encourage entrepreneurship, but when they don’t raise enough revenue to pay our bills, they add to interest costs on the debt, gradually eroding support for investments in people, education, and similar efforts.

It’s not that liberals and conservatives advocating these older agendas don’t care about mobility. They’ll tell you that people with more sustenance will be able to work and study harder and entrepreneurs facing lower tax rates will create more jobs. But they try to claim too much for agendas that, though successful on some fronts, did not improve mobility in recent decades. The proof is in the pudding.

Raising these issues threatens those who fear that acknowledging failure on any front merely empowers those who advocate for the opposing agenda. And in today’s chaos that passes for policymaking, that is probably true. I don’t even know in what galaxy to place debates over previously nonpartisan issues like extending the debt ceiling so Congress can pay off its bills.

For me, it isn’t about abandoning the past. It’s simply about moving on.

Can Foundation Giving Relate Better to Society’s Needs Over Time?

Posted: June 18, 2013 Filed under: Economic Growth and Productivity, Income and Wealth, Nonprofits and Philanthropy, Shorts, Taxes and Budget 1 Comment »Charitable organizations form a vital part of America’s safety net. Ideally, foundations would be able to make greater payouts in hard economic times when needs are greatest. Unfortunately, the design of today’s excise tax on foundations undermines and in fact discourages such efficiency.

Under current law, private foundations are required to pay an excise tax on their net investment income. The tax rate is 2 percent, but it can be reduced to 1 percent if the foundation satisfies a minimum distribution requirement. The dual-rate structure and distribution requirements obviously introduce complexity. The stated purpose of the tax in legislative history—to finance IRS activities in monitoring the charitable sector—has never been fulfilled.

In the recent recession, the impact of the excise tax was especially pernicious, as it penalized those that maintained their level of grantmaking.

How? As Martin Sullivan and I first described in 1995, the excise tax penalizes spikes in giving; under the current formula, a temporarily higher payout results in a higher excise tax when payouts fall back to previous levels. A foundation that reduced its grantmaking during the last recession would not be subject to an increased excise tax because the amount the foundation paid out would be measured as a share of current net worth.

One proposal would replace the excise tax with a single-rate tax yielding the same amount of revenue. While a flat-rate tax would remove the disincentive to raise grantmaking in bad times, it still raises taxes for some foundations and not others.

A related law applying to foundations is the required payout rate, now set at 5 percentage points. Many experts have debated how high that rate should be. The current rate is believed to approximate the long-term real rate of return on a foundation’s balanced portfolio of assets. However, if foundations follow a strict rule of paying out the minimum 5 percent every year, they, too, will be operating procyclically, paying out more in good times when stock markets are high and less in bad times.

If we wish foundations to operate more countercyclically—to pay out more when needs are greater—we need to address both the excise tax and the natural tendency, reinforced by a minimum payout requirement, to make grants and payouts as a fixed percentage of each year’s net worth.

Austerity, Stimulus, and Hidden Agendas

Posted: June 11, 2013 Filed under: Columns, Economic Growth and Productivity, Taxes and Budget 2 Comments »Nothing better exemplifies our gridlock over the future of 21st century government, as well as how to recover from the Great Recession, than the false dichotomy of austerity versus stimulus.

The austerity thesis, reduced to its simplest form, suggests that government has been living beyond its means for some time, only exacerbated by the actions that accompanied the recent economic downturn. Sequesters, tax increases, and spending cuts become the order of the day.

The stimulus hypothesis, reduced also to simplest form, suggests that more government spending and lower taxes puts money in people’s pockets and helps cure a country’s economic doldrums. Once the economy is doing better, government spending will naturally fall and taxes rise.

The debate then plays out largely over deficits: do you want larger or smaller ones?

But reduced to this form, the debate is a fallacy, for several reasons.

First, one must define larger or smaller relative to something. Last year’s spending or taxes or deficits? What’s scheduled automatically in the law? The public debate often glosses over these issues. Which is more expansionary when keeping taxes at the same level: an economy whose growth in spending is cut from 6 to 4 percent or one whose growth is increased from 1 to 3 percent?

Second, a country’s ability to run deficits depends on its level of debt. A recent debate over whether at some point higher debt starts to slow economic growth doesn’t change the fact that lenders want to be repaid. People won’t loan to Greece now, but they still find the U.S. Treasury securities a safe haven for their money.

Third, and by far the most important, what timeframe is involved? Is the Congressional Budget Office pro-austerity or pro-stimulus when it concludes that sequestration hurts the economy in the short run, but is better in the long run than doing nothing about deficits? No one on either side suggests that debt can grow forever faster than the economy. Everyone implicitly or explicitly believes that to accommodate recessions when debt grows faster there are times when debt must grow slower.

So where’s the rub? Here you must understand the emotional systems, usually veiled, that lie behind those on both sides trying to force the problem to an either/or solution.

Start with hardline austerity advocates. Many of them don’t just want smaller deficits. They want smaller government—or, at the very least, they want to prevent the government from taking ever larger shares of the economy, even given changing demographics. Essentially, austerity advocates don’t trust their pro-stimulus adversaries, some of whom can almost always find an economy going into a recession, in a recession, coming out of a recession, or attaining a lower-than-average growth rate and, therefore, needing some form of stimulus. Austerity advocates have learned from long experience that once government spending is increased, it’s hard to reduce. So they feel they have to get what deficit reduction they can now that the public’s attention to recent large debt accumulations is creating pressure to act.

Now for many the hardline stimulus advocates, their support for additional temporary government intervention cannot be entirely disentangled from their sympathy for a larger future government. Else why not agree to cut back now on the scheduled acceleration of entitlement programs, particularly fast-growing health and retirement programs? That would bring the long-run budget, at least as currently scheduled, back toward balance. It would simultaneously please many of their austerity opponents and allow for more current stimulus.

The hidden agendas are complicated further by inconsistencies on both sides. Many hardline austerity advocates, at least in the United States, don’t want cuts to apply to defense spending. For their part, many hardline stimulus advocates would be glad to pare growth in tax subsidies.

Regardless, the dichotomy falls apart once one realizes that a solution can involve a slowdown in scheduled growth rates in spending and a higher rate of growth of taxes, accompanied by less short-run deficit reduction and an abandonment of poorly targeted mechanisms such as sequesters.

Consider the buildup of debt during World War II, the last time we saw U.S. levels above where they are today. Debt-to-GDP fell fairly rapidly after the war all the way until the mid-1970s. While the growing economy certainly helped, tax rates that were raised substantially during the war were largely maintained afterward, and spending had essentially no built-in growth (actually huge declines when the troops came home). Just the opposite holds now even with recovery: there are limited tax increases to pay for past accumulations of debt or wartime spending, and spending is scheduled to grow long-term, even after temporary recession-led spending and defense spending on Afghanistan declines.

Both sides—pro-austerity and pro-stimulus—want desperately to control an unknown future, either by not paying our current bills with adequate taxes or by maintaining built-in growth rates in various programs, mainly in health and retirement. The false dichotomy between austerity versus stimulus has fallen by the wayside, and what we see through the veil are two sides in mutual embrace trying to control our future, whatever the cost to the present.

Growth in Income and Health Care Costs

Posted: June 4, 2013 Filed under: Columns, Economic Growth and Productivity, Health and Health Policy, Income and Wealth, Race, Ethnicity, and Gender 4 Comments »Worried about the stagnation of income among middle-income households? Or about the growth in health care costs? The two are not unrelated. In fact, middle-income families have witnessed far more growth than the change in their cash incomes suggest if we count the better health insurance most receive from employers or government. But is that all good news? Should ever-increasing shares of the income that Americans receive from government in retirement and other transfer payments go directly to hospitals and doctors as opposed to other needs of beneficiaries? Should workers receive ever-smaller shares of compensation in the form of cash?

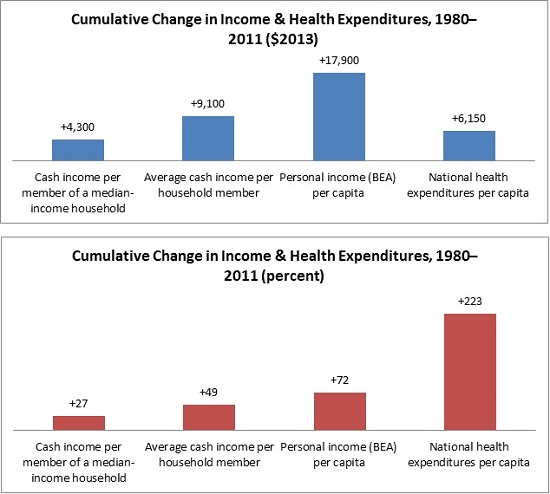

The stagnation of cash incomes in the middle of the income distribution now goes back over three decades. Consider the period from 1980 to 2011. Cash income per member of a median income household, which includes items like wages and interest and cash payments from government like Social Security, only grew by about $4,300 or 27 percent over that period, when adjusted for inflation. From 2000 to 2010, it was even negative. Yet according to data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis, per capita personal income—our most comprehensive measure of individual income—grew 72 percent from 1980 to 2011.

How do we reconcile these statistics? By disentangling the many pieces that go into each measure.

Growing income inequality certainly plays a big part in this story: much of the growth in either cash or total personal income was garnered by those with very high incomes. So the growth in average income, no matter how measured, is substantially higher than the growth for a typical or median person who shared much less than proportionately in those gains. But personal income also includes many items that simply don’t show up in the cash income measures. Among them is the provision of noncash government benefits, such as various forms of food assistance.

Health care plays no small role. In fact, real national health care expenditures per person grew by 223 percent or $6,150 from 1980 to 2011, much more than the growth in median cash income. If we assume that the median-income household member got about the average amount of health care and insurance, then we can see how little their increased cash income tells them or us about their higher standard of living.

Getting a bit more technical, there’s a danger of over-counting and under-counting health care costs here. Some of the median or typical person’s additional cash income went to extra health care expenses, so the additional amount he/she had left for all other purposes was even less than $4,300. However, individuals pay only a small share of their health care expenses; the vast majority is covered by government, employer, or other third-party payments. So, roughly speaking, typical or median individuals still got well more than half of their income growth in the form of health benefits.

The implications stretch well beyond middle-class stagnation. Employers face rising pressures to drop insurance so they can provide higher cash wages. For instance, providing a decent health insurance package to a family can be equivalent roughly to a doubling of employer costs for a worker paid minimum wage. The government, in turn, faces a different squeeze: as it allocates ever-larger shares of its social welfare budget for health care, it grants smaller shares to education, wage subsidies, child tax credits, and most other efforts. Additionally, the more expensive the health care the government provides to those who don’t work, the greater the incentives for them to retire earlier or remain unemployed.

In the end, the health care juggernaut leaves us with good news (that our incomes indeed are growing moderately faster than most headlines would have us believe) as well as bad news (that health care remains unmerciful in what it increasingly takes out of our budget).