Getting the Facts Straight on Retirement Age

Posted: March 12, 2013 Filed under: Aging, Columns, Economic Growth and Productivity, Income and Wealth, Race, Ethnicity, and Gender 16 Comments »On the front page of the Washington Post on March 11, 2013, Michael Fletcher connects the different life expectancies of the poor and rich to the debate over whether Social Security should provide more years of retirement support as people live longer. He mistakenly leaves the impression that adjusting the retirement age for increases in life expectancy hurts the poor the most. In fact, such adjustments take more away from the rich. Let me explain how.

Suppose I designed a government redistribution policy that increases lifetime Social Security benefits by $200,000 for every couple with above-average income that lives to age 62. For every couple with below-average income that reaches age 62, my program would increase benefits by $100,000.

Does this sound like a good policy? Well, that’s exactly what Social Security has done by providing all of us with increasing years of retirement support. People retiring today get many, many more years of Social Security benefits than those retiring when the system was first created. And, the primary beneficiaries are the richer, not the poorer, among us. Throwing money off the roofs of tall buildings would be a more progressive policy, since the poor would likely end up with a more equal share.

Why, then, do some Social Security advocates oppose increasing the retirement age? Because the $100,000 in my example could mean proportionately more money for the poor. For instance, it might add one-tenth to their lifetime earnings (of, say, $25,000 a year for 40 years of work, or $1 million over a lifetime), while the $200,000 to rich individuals might add only one-fifteenth to their lifetime earnings. As it turns out, even this assumption isn’t correct, but let’s assume for the moment it is.

Why would we want to redistribute that way? Following that logic, we should have protected the jobs of all the Wall Street bankers after the recent crash because their wages represented a smaller share of their income than the wages of poorer workers providing support services. Or perhaps we should provide $5,000 of food stamps to those making more than $50,000 and $3,000 of food stamps to those making $20,000; after all, the latter would still get proportionately more.

As it turns out, however, more years of retirement benefits don’t benefit the poor proportionately more than the rich. Yes, the poor have lower life expectancies, but other elements of Social Security offset this factor. A greater share of the poor doesn’t make it to age 62, so a smaller share of them benefit from expansions in years of retirement support. More importantly, those who are poorer are more likely to receive disability payments that aren’t affected one way or the other by the retirement age; hence, again, a significantly smaller share of them benefit from more retirement years. Other regressive elements such as spousal and survivor benefits also come into play for reasons I won’t further explain here. Empirically, these various factors add up in such a way that increases in years of benefits help those who are richer and those who are poorer in ways roughly proportionate to their lifetime incomes.

Setting these disputes aside, the higher mortality rate of the poor at each age does raise many legitimate policy issues. Recipients who stopped smoking a couple of decades ago, for instance, have been rewarded with more and more years of retirement benefits. This, along with many other features of Social Security, such as the design of spousal benefits already noted, does mean that the system is a lot less progressive than most believe.

The more fundamental issue, then, is whether we should better protect those with low-to-average wages during their lives. I believe we should but through better-targeted mechanisms, such as minimum benefits, progressive adjustments to the benefit formula, wage supplements to low-wage workers, and other devices that don’t spend most of the program’s funds on ever more years of retirement for those who are richer.

Yet another reason to worry about the retirement age is that the failure to adjust over time—a couple retiring today at 62 can now expect about 27 years of benefits—has meant larger shares of payments go to those closer to middle age, in terms of remaining life expectancy. Almost every year, a smaller share of payments goes to those who are truly old and more likely to need assistance.

In sum, the recent widening gap in life expectancy, likely due to such factors as differential rates of cigarette smoking, deserves serious attention. But let’s not pretend that throwing money off the roof, or providing more years of retirement support to the non-disabled who make it to age 62, addresses the core issue. There are better ways to compensate than converting a system originally designed to protect the old into one offering middle-age retirement to everyone.

State Pension Reform: Is There a Better Way?

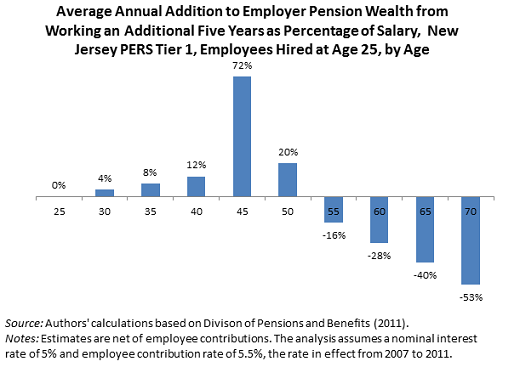

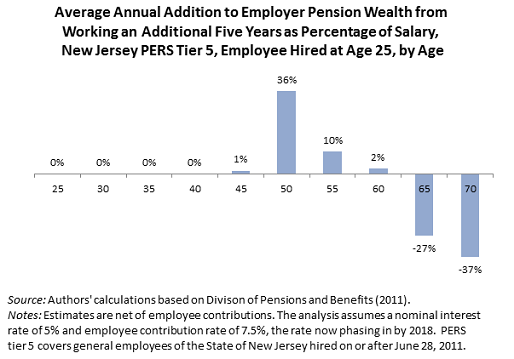

Posted: July 26, 2012 Filed under: Aging, Income and Wealth, Race, Ethnicity, and Gender, Shorts 1 Comment »Are the benefits of state pension plans allocated efficiently and fairly, and do they attract the best workers for the amount of money spent? Consider the graphs below for the state of New Jersey, which are somewhat typical of state pension plans in many other states. They show the annual pension wealth increments provided by the state for working for the state for five additional year for typical tier-1 (pre-reform) and tier 5 (post-reform) employees hired at age 25. Younger workers used to get very little, now they get nothing. Middle age workers get locked into the employment, regardless of how well it fits their skills or the needs of the state at that point. And older workers get very negative benefits, though at later ages than in the pre-reform era. For further details, see a paper (and two briefs) I published with Richard W. Johnson and Caleb Quakenbush, entitled “Are Pension Reforms Helping States Attract and Retain the Best Workers?”

Could the Fight Over Marriage Affect Welfare and Tax Reform?

Posted: June 15, 2012 Filed under: Columns, Income and Wealth, Race, Ethnicity, and Gender, Taxes and Budget 4 Comments »Could the debate over gay marriage force the federal government to correct the crazy ways our broken welfare and tax systems treat the institution? So far, the marriage discussion has focused on the rights of different couples to wed, but the issue stretches way beyond this rather limited focus. The government today spends hundreds of billions of dollars annually both fining and subsidizing marriage. Yet the funds are distributed unevenly and poorly, typically penalizing married couples during their childraising years and rewarding them when the children are grown. They also tend to penalize marriage more for those who are poorer. Those who can gain the most from this system are those who, legality aside, consider a marriage vow optional.

As social pressure for adults to marry has declined, government marriage penalties have risen and reinforced that decline. Though many forces are at play in both developments, these trends have made a huge equity issue loom ever larger. Congress gives primary status in our social welfare and tax systems to those who don’t care for marriage that much one way or the other. They can opt not to marry when there are penalties and opt into the system when there are bonuses. As one result, what used to be called a marriage penalty should now be relabeled the marriage vow penalty. Couples who choose to marry—for love, family, religion—despite the penalties they’ll incur are the ones who lose.

What makes the fight over gay marriage so interesting in this respect is that it is between two groups who hold marriage vows sacred but do not want the other group defining who is qualified to take them. Yet when it comes to the state, and how it bases support on marital and family status, neither group is the most advantaged in the current system; rather it is those who treat the marriage vow as secular or utilitarian, not sacred.

A little explanation. Marriage penalties today largely arise in spending and tax subsidy programs largely as a byproduct of historic efforts to support children. Outside of public education, these supports for children are largely means tested—that is, the benefits are removed as family income increases. And marriage tends to increase that income. (Historically penalties also arose for some joint returns filing income tax returns, although less so than in the past.)

Take a low-income mother who makes about $10,000 a year. If she simply marries or remains married to a moderate-income worker who makes about $25,000, their family income goes up and she can lose earned income credits, supplemental nutrition assistance (formerly called food stamps), Medicaid, and, under recent health reform, subsidies to buy health insurance. By not marrying, the couple’s combined income often can be $5,000 or $10,000 higher.

Many of those benefit programs are available to everyone raising children, including you and me, in months or years when our incomes fall low enough. If households further qualify for welfare or housing or other assistance that is not so universally available and sometimes requires coming off a waiting list, the penalties are even higher.

In some low-income communities, marriage is now the exception rather than the rule. In effect, not taking the marriage vow is the primary “tax shelter” available for low- and moderate-income individuals, and aggregate incomes in those communities would fall substantially should they start to marry in greater proportions. At the same time, a very large percentage of our children are now raised by one parent. Isabel Sawhill, a Senior Fellow at the Brookings Institution recently reminded us of the negative societal consequences of this trend.

On the flip side of the social welfare ledger, Social Security provides very large subsidies for spouses. Unlike private pensions, spousal and survivor benefits are paid for by all workers, including those who are ineligible because they were married for less than 10 years. And workers get these benefits for their spouses independently of raising children or paying a dime more than other workers. As a result, many workers, especially low-income women raising children, pay more taxes and raise more children than many Social Security spouses and survivors who do neither but still get higher benefits. Think of this marriage bonus as a penalty for singles, including abandoned parents.

In effect, the single parent gets penalized for marrying when raising children, then for not marrying when close to retirement.

The income tax rate schedules, in turn, now mainly provide marriage bonuses for middle, upper-middle, and some richer families, especially where one partner receives a disproportionate share of the earnings. When these tax and subsidy systems are considered together for the working population, penalties are more likely to apply to poorer households and bonuses to richer households.

These structures, unfairly and inefficiently designed in the first place, have become increasingly outdated relative to the conditions and needs of the modern society. Yet year after year, both political parties have indiscriminately created and added to these various marriage penalties and subsidies. Because so much money is at stake, they have been afraid so far to engage in any fundamental reform.

As wedding vows become more of an optional item for those who do not believe in the institution of marriage, one wonders how long this increasingly inequitable structure can stand.

How Social Security Can Costlessly Offset Declines in Private Pension Protection

Posted: June 30, 2010 Filed under: Columns, Economic Growth and Productivity, Income and Wealth, Race, Ethnicity, and Gender Leave a comment »Here’s a well-kept secret: the Social Security Administration today offers one of the best investment options anywhere. This great deal allows individuals to add to the Social Security annuities that they already qualify for at age 62. Since the classic pension plans that used to provide workers with private annuity payments until death are fast disappearing, this option gets more valuable by the day.

This add-on, like the basic Social Security annuity, is as insured as an investment can get, doesn’t fluctuate with the stock market or economic downturns, and rises in value along with inflation. The rate of return is decent too.

So where’s the rub? This option is buried in Social Security’s overlapping and confusing provisions. That’s why so few people who could really use this extra protection end up understanding, much less buying, it.

My suggested reform: daylight this hidden concoction of provisions and convert it into an open, understandable, and far more flexible option. Doing so would favor saving and reward work while better preparing elderly people for their very high likelihood of living to age 80 and beyond. And it needn’t cost anything.

How? As part of a broader Social Security reform of the retirement age. Instead of confusing notions of early retirement at 62 and normal retirement at 66, surrounded by formal “earnings tests” and “delayed retirement credits,” adopt a simpler annuity option. (Stay tuned for some definitions of terms, but keep in mind that the very fact that most people misunderstand how all these provisions interact proves the need for reform.)

Under my plan, the Social Security Administration would simply tell people their benefit at a specific retirement age (either an earliest age or a “normal” age). Then it would show a simple set of penalties or bonuses for withdrawing money or depositing it with Social Security. It could fit on a postcard.

Although not essential, I would sweeten the deal for people who not only delay benefits but also work longer and pay extra taxes. With this additional option, the penalties would be higher and the bonuses greater for workers than nonworkers. For instance, the employee portion of Social Security tax could be credited as buying a higher annuity. These extra bonuses could be financed by making the up-front benefit available at the earliest retirement age a bit lower for higher-income beneficiaries who stop working as soon as possible. This combined strategy backloads benefits more to later years when people are older and frailer, and it encourages work—an approach I have advocated, as does Jed Graham in his recent book, A Well-Tailored Safety Net.

The simple, easily understood bonuses would basically be annuities with higher payouts than standard Social Security benefits. They could be purchased whether a worker quit work or not. As people can today, many would purchase these fortified annuities by forgoing all their Social Security checks for a while. But, unlike today, they could also specify how much of their Social Security check they would forgo or send a separate check to Social Security.

How would the poor fare under this new approach? To protect them, let’s increase minimum benefits under Social Security so most lower-income households end up with higher lifetime Social Security benefits—regardless of what other reforms may be undertaken. Say, for example, we accept the additional option of lowering the up-front benefit for those who totally stop work as soon as possible in their 60s by 10 percent but bump up a minimum benefit to $900. Then someone who used to get more than $1,000 could get less in those early years but has a great option for beefing up the annuity in later years. Someone formerly getting $1,000 or less would not lose out at all, even in early years of retirement.

Helpful employers (or 401(k) account managers, financial planners, or banks) could help workers take advantage of this great annuity option. As one example, they could easily map out a range of schedules for drawing down private assets or taking partial Social Security checks for a couple of years in exchange for better old-age protection—higher annual, inflation-adjusted payments—in later years.

Setting up a similar payout trade off today is sometimes possible if you’re not easily discouraged, but you wouldn’t get much credit for additional taxes. In fact, you can even send back Social Security money received in the past to boost future benefits. (Who knew?)

Too bad most people believe that if they hit age 62 in 2010, the “earnings test” they face is a “tax” up to the age 66 that reduces benefits by 50 cents for every extra dollar they earn between $14,160 and $37,680. But that’s what they think, and they calculate this “tax,” add it to their other tax burdens, and quickly decide that they’re better off retiring. Yet, that’s not really right. In truth, if they forgo some benefits now, they have just bought an additional annuity, and their future annual Social Security benefits go up permanently by roughly $67 for every $1,000 in Social Security benefits they temporarily forgo for one year.

Today, those age 66 to 70 have different options than when they were younger than 66. This only adds to the confusion. They no longer must purchase the annuity (face the earnings test) if they work, but they are free to take a delayed retirement credit—this time, $80 in every future year of retirement for each $1,000 of Social Security benefit forgone for one year . But they often don’t realize that they don’t need to start benefits at retirement. By living off other assets awhile, even a month or more, they can convert some of their riskier assets into a higher Social Security annuity asset.

Just to further complicate things, Social Security administrators often tell people to “get your money while the getting is good” when, in fact, it’s risky to draw down benefits too soon when one member of a typical couple is likely to live for 25 or 30 years after age 62.

The type of reform I’m proposing could never be timelier. Had more older individuals taken advantage of this simplified option before the stock market crashed, they’d be a lot more secure today. Similarly, folks retiring today with many of their assets tied up in either risky or very low return investments could sleep better if they take this option.

Why wait? Let’s redesign and simplify the Social Security super-structure surrounding retirement ages, related earnings tests, and delayed retirement credits. Let’s help more retirees build up additional annuity protection in old age, make more transparent the advantages of delaying benefits, reward better those who work longer and pay more taxes, and create simpler and more flexible options for depositing different sums of money to purchase larger annuities in Social Security.

How Middle-Age Retirement Adds to Recession Woes

Posted: June 2, 2010 Filed under: Aging, Columns, Race, Ethnicity, and Gender Leave a comment »As the nation struggles to deal with both an unsustainable budget and an economy in need of growth, one really bad idea needs to be nipped in the bud. Expressed in various forms, the idea is that baby boomers’ retirement isn’t really a problem until the economy fully revives, that people in late middle age should quit to make room for younger workers, and that the multi-decade failure to adjust retirement ages for longer lives is a can we can keep kicking down the road. Let’s face it: our retirement system for middle-agers is hurting us financially right now.

Bad economics, this idea in its various guises also invites a less-than-full economic recovery. The Great Recession is starting to spark notions heard in the Great Depression, when older workers were also encouraged to retire. It didn’t do any good: employment rates stayed low for over a decade. It was a bad idea then, and it’s a bad idea now.

The economy-wide perspective differs from the firm-level perspective: when people work more, they generate income and spend that income on goods or services—increasing not just the supply of workers, but also the demand for other jobs. Yes, a worker who hangs onto a $50,000 job might prevent someone else from taking that exact job. But that worker then spends (or invests) $50,000 on goods and services that others must produce in other jobs.

Let’s put it another way. Suppose a firm in Detroit fires a younger worker, who makes unemployment claims, and an older worker, who decides to retire earlier than planned but still doesn’t get counted in the ranks of the unemployed. Is Detroit any better off because the older worker lost his job, even though, unlike the younger worker, he didn’t add to unemployment statistics? Of course not. They both add to Detroit’s recession woes. And they both add to the “nonemployment” rolls.

How much of an issue is the retirement of older workers? In the short run, it’s less important than job losses due to the collapse of the financial and housing markets. Longer run, however, it may be far more serious. If people simply retire at the same ages over the next 20 years as they do today, then the employment drop is equivalent to an increase in the unemployment rate of close to one-third of 1 percent every year. Two decades or so from now, the increase in nonemployment would have about the same effect as a 7 percentage point increase in the unemployment rate. And this increase would be permanent, not just a temporary, recession-led blip.

We don’t really have to wait 20 years for the bad economic news to register either. Contrast how we got out of other recessions in earlier decades. Government deficit-led demand alone didn’t do the trick. Counting both those employed and those looking for work, we also had a labor force increase of 29 percent in the 1970s, 18 percent in the 1980s, and 13 percent in the 1990s. This last decade is more of a mixed bag, mainly because of the recession, and for each of the two decades from 2010 to 2030, the Census is expecting increases of only about 7 percent. Even that projection assumes some increase in the proportion of older age groups that work. Despite many past recessions with large annual increases in unemployment, by the way, 2009 was the first year in almost six decades with negative labor force growth.

Additional labor force participants didn’t just increase the supply of workers; even when they started out with meager jobs, they boosted production and income and the demand for goods and services that helped pull the nation out of past recessions. With lower labor force growth today, there’s less of the extra demand that a large net increase in the workforce stokes.

Well, you might say, government can come to the rescue by making up for lost wages. To some extent, that’s true. But government help doesn’t stop unemployment or nonemployment from rising and taking a toll on the economy as a whole, even if that help lessens the decline in demand. In any case, nobody who does arithmetic pretends that government can run large enough deficits to continually make up for everyone’s lost income. Moreover, we’ve hit the point where efforts at deficit reduction are going to be decreasing—certainly not increasing—government demand.

How about the effect of the international economy? Doesn’t any multiplier or snowball effect—from one nonemployed person leading to another—weaken when demand can come from abroad, not just from home? True again. But, by the same token, any multiplier effect from government-created demand also shrinks. That said, the developed world shares both a slowdown in labor force growth and a recessionary slowdown in demand. In both cases, a mutual response is better than an individualized one.

My basic point is simple: when it comes to looking at recessions and the potential for renewed growth, look at the nonemployment rate, not just the unemployment rate. The first wave of baby boomers hit 62—the youngest you can get Social Security benefits—in 2008, and that downtick in labor force and employment came just as the recession began to hit. Boomer retirement may add only moderately to the nonemployment rate in any one recession year, but, unless moderated, its negative force will build steadily year after year for decades.

Encouraging work in late middle age alone won’t end the recession or clean up our fiscal mess. And many of those facing nonemployment, whether older or younger, have little control over the situation. But when our elected officials delay action—for instance, continuing to encourage retirement in late middle age and failing to start dismantling barriers to work at older ages—they hurt the economy recovery now, not just economic growth over the long term.

On the positive side, my reading of the data tells me that there’s a large undercurrent of demand for older workers, who have now become our largest store of underused human capital and potential. But activating that potential partly requires lowering the barriers and dams in the way. If I’m right, older workers can significantly boost economic output, increase government revenues, and add to their own incomes. Along the way, they can help us recover from recession—if we let them.

Now To Really Tackle Discrimination

Posted: July 10, 2007 Filed under: Columns, Crime and Justice, Race, Ethnicity, and Gender Leave a comment »Louisville, Kentucky, is a nice town. I’m biased—I grew up there. It’s not South, North, East, or West in make-up, but a bit of all four. It is home to horse racing and bourbon, but also to the world’s largest producer of Braille books and the Louisville Slugger baseball bat.

Louisville is back in the news these days because its plan for integrating schools, like Seattle’s, was overturned recently by the Supreme Court. However divided is opinion over this decision, it should force us to look more deeply into what a well-integrated society means and requires. Public debate should range far beyond the use of race as a factor in determining which kids can go to which schools. Besides school systems, we should be challenging institutions ranging from universities to charity and corporate boards to governments on ways to diversify that go well beyond simple ratios of blacks to whites or females to males.

Return to Louisville. In 2000, it achieved what many major cities around the nation must envy. It integrated into a single jurisdiction the former city of Louisville, with its one-third black population, with the surrounding Jefferson County, which has a much larger concentration of whites. That’s right. They merged, and the suburbs basically agreed to work with the inner city on issues ranging from school integration to money per pupil to access to government support services. Now this may only be one step, but it could matter more to minorities in Louisville than whatever change in its schooling formula the recent Supreme Court decision might trigger.

Schools can be integrated in many ways besides racially. In Alexandria, Virginia, for instance, the high school integration problem was solved simply by merging all the high schools into one. A 2000 movie named “Remember the Titans” chronicled that event (at least as well as Hollywood could do it; Alexandria, next to the nation’s capital, was described as a small southern town where football was a way of life).

Many school systems can also use basic statistics better to ensure the well-being of all students. The new court decision doesn’t prevent school districts from tying admission or access to alternative schooling to family need or income or homeownership or housing value—replacing racial integration with class integration, but almost certainly promoting racial equality in the process. Even more to the point, districts should be measuring the improvement of every student in every environment, constantly re-jiggering requirements, school structures, quality of teachers, number of teachers’ aides, early childhood education, and whatever is under their control to serve all our children.

We’ll never integrate society solely by pressuring primary and secondary schools. That’s why major universities that claim to have integrated are now coming under greater scrutiny. Harvard or Yale might have little problem taking in the children of doctors and generals and lawyers who also happen to be minorities, but, even with all their intellectual firepower, most elite schools provide little data on their record in serving those from poorer or disadvantaged households. Some recent studies, for instance, point to the low percentage of students at these schools who were admitted with income-related Pell grants.

If we really want an integrated society, we should re-engage the working world, not just schools, to meet that challenge. Consider boards of directors. My colleague, Francie Ostrower, recently chronicled the low participation of minorities on charity boards—even some of those serving minorities. As for corporate boards, the glass ceiling is well noted, but even when it is cracked, boards often tap the same minority person or woman over and over again rather than reach out to more people from largely excluded classes.

Closer to home, residential segregation lives on, thanks to various ordinances, such as minimum size housing or lots. Some rules prevent two families from moving to a single house in a neighborhood where schools are better—even when their combined families might have fewer total members than a single family in a similar home. How about zoning that encourages McMansions to be built in high—land value areas to the exclusion of high-density developments that the middle class could afford?

Moving toward a truly integrated society—like combining Louisville and Jefferson County into a single jurisdiction—requires hard work, creativity, and a reshuffling resources as opportunities arise. A single statistics or ratios can’t be the measure of success. Whatever else the recent Supreme Court sets in motion, let’s hope it catalyzes a real public discussion of the many dimensions of an integrated society and how to promote opportunity for all.

Pension Plan Discrimination Against the Short-Lived

Posted: May 2, 2007 Filed under: Aging, Columns, Race, Ethnicity, and Gender Leave a comment »Many pension plans pay out benefits over a worker’s remaining life. Perhaps inadvertently, they then discriminate against groups with shorter life expectancies. Losers include those with poorer health, less education, and more physically demanding jobs. Racial groups with higher mortality rates, like blacks, also lose. This discrimination, however, can largely be overcome with compensating mechanisms.

Retirement plans are of two types. One type revolves around deposits to such accounts as 401(k) plans and individual retirement accounts (IRAs). Typically, when employers pay compensation to this type of retirement plan, the benefits are proportional to cash wages and of equal benefit to all workers at the same wage level. The more classic pension plan, on the other hand, has a formula for “replacing” wages over a worker’s remaining life. For instance, a firm might pay workers with 30 years of service an annual benefit equal to 20 percent of pay earned during their highest earning years.

At first the classic pension plan might appear to treat equally those workers with the same jobs, wages, and time with the firm. But it does not. Why the discrimination? Converting benefits to annuities gives those with shorter lives fewer benefits than those with longer lives.

Generally speaking, we want to encourage annuities. They do a lot of good things. As death is a random event, most pensioners are happy to get the extra protection in case they live long lives. Annuities help prevent our living standards from falling as we age. Social Security, for these reasons, pays out benefits as an annuity to meet its social policy objective of “insuring” for those with long lives.

Still, consider the extreme case of George, who is in poor health throughout his life, works for a firm for 30 years, gets no survivor benefits, and dies at eligibility age. The firm would pay George zero pension benefits. Meanwhile, Paul, who is in very good health and can expect to live a long life, receives substantial pension benefits. The discrimination isn’t just among individuals, like George and Paul, but also among groups. Blue-collar workers might do worse than white-collar workers and blacks worse than whites.

Social Security shows us that it is possible to deal with this type of discrimination through offsetting mechanisms. For instance, Social Security has a progressive benefit formula that provides higher benefits relative to past lifetime earnings (higher “replacement wages”) to those with lower-than-average lifetime earnings. Because lower earnings are correlated with lower life expectancy, people from educational, racial, and other groups with lower life expectancy are more likely to get equal returns on their Social Security contributions or taxes

Unlike Social Security, classic pension plans don’t have access to lifetime earnings records, so they can’t use the same offsetting formula. To provide equal pension pay for equal work, other offsetting mechanisms must be tapped. A simple example is life insurance, which tends to favor those with lower life expectancies. An adequate amount of life insurance provided in addition to the classic pension plan could compensate some of those who lose out because of the annuity feature of the plan. However, such life insurance would need to carry forward beyond employment years since people with shorter life expectancies often do make it to retirement age.

Another simple compensating device would be to require that annuities contain a certain minimum number of years of payments to heirs if the worker dies. Such “life certain” policies can insure, for instance, that even if a worker dies at retirement age, at least 15 years of payments would be made. These rules could also be used to insure more equal treatment of those with lower-than-average life expectancies who convert their 401(k) and similar balances into annuities. Firms sometimes increase the probability that benefits will be paid for at least some years by providing survivor benefits, but those benefits often don’t help single workers.

While classic pension plans have been on the wane in the private sector, millions of government workers participate in such plans. Federal, state, and local governments could examine and amend these pension plans to reduce discrimination among their own workers. Similarly, protections should be put in place for those purchasing annuities with their 401(k) and similar accounts. Future retirement and pension plan reform must start to address this discrimination. Short lived shouldn’t mean short changed.