Accounting Better for the Federal Budget

Posted: March 4, 2008 Filed under: Columns, Taxes and Budget Leave a comment »Almost nothing better reflects our federal government priorities than the budget. In the to and fro of federal budgeting, we decide how to spend about one-fifth of our entire national income, or, by another calculation, all the federal taxes we collect—and then some! The arcane rules governing how budget numbers are presented, however, totally obscure what’s really happening. Turning out even more lights, every modern president and Congress play an accounting game that makes it seem like they aren’t accountable for how spending changes over time.

The comedian Flip Wilson used to complain, “The devil made me do it.” Our elected officials do him one better almost by saying “The budget made me do it.” Like Flip, however, they have complete charge over their own devil.

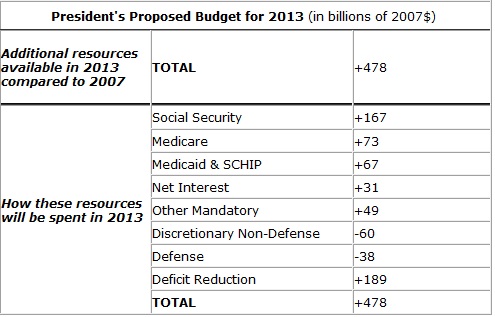

Here is a simple table from President Bush’s 2008 budget documents showing the spending changes he suggests should occur by 2013. I use the word, “suggested,” because these numbers sometimes show little resemblance to proposals.

The message is clear: of the $478 billion extra in real revenues that the president proposed collecting in 2013 over and above revenues in 2007—largely due to economic growth–Social Security would get about 35 percent, Medicare and Medicaid about 29 percent. Defense not only would get no additional spending out of these additional revenues, it would drop dramatically in real terms

Wait, you say, didn’t the headlines proclaim that President Bush proposed big increases for defense and big cuts for Medicare and Medicaid? Well, he did and he didn’t. That’s why the budget in its standard form is so confusing.

What the president did was propose a lot more for defense for one year (2009) and then suggest in his budget accounting that those increases would immediately tail off so he could get his future deficits to look better. All those newly hired troops and defense industry workers presumably would be fired in the next couple of years. As for the costs of the war in Iraq, they are on top of this one-year buildup, but the president shows only one part of one year’s expense in the budget.

On the Medicare and Medicaid front, the President did propose cuts. But those cuts were against a fairly high growth path. Meanwhile, the Social Security budget would keep swelling as baby boomers retired and because new individual accounts for workers would be funded under his proposals.

The confusion surrounding this year’s budget isn’t very different from what we’ve seen many times in the recent decades. The mistake is thinking that merely electing new people will make the problem of misleading budgets go away. No matter who controls the White House or Congress, major fixes in how we budget must be a reform priority.

For starters, the budget needs to be presented in a way that allows Americans to hold the president’s and Congress’ feet to the fire. Our leaders must be held accountable for both for the laws they make and for changes born of their often-calculating inaction. They must accept responsibility for both new enactments and whatever glide path they leave us on for expenditures now outside the annual appropriations process. Today’s scorecard emphasizes the first and hides the second.

A better scorecard would present first all the changes that the president proposes through both direct and passive action. Current spending levels, no matter what the legislative source, would be compared first to past spending levels. We essentially get this type of readout now only for “discretionary” spending—that dwindling share of the pie that isn’t already committed to ongoing programs.

Historically most spending was “discretionary” or up for grabs every year—permanent mandatory or entitlement programs were either small or non-existent. Hence, my proposed reformed scorecard represents nothing more than a return to the basic budget accounting that occurred naturally in the past.

One great advantage to focusing first on the total change in spending levels is that cuts look like cuts and increases like increases. Suppose an education program without automatic growth built in would need to grow by $5 billion just to keep up with inflation, while the president proposes a legislative boost of only $1 billion. Then the budget’s initial scorecard on total proposed change should show a $4 billion cut in real (inflation-adjusted) terms as what he would like to achieve in aggregate. Similarly, if a health program would grow automatically at $70 billion, but $20 billion of that increase is just inflation, and the president proposes a $10 billion legislated cut from the current law growth path, our revised table would show that on net he suggested a $40 billion real expansion.

Other budget accounting is still required. For a variety of legislative purposes, it is necessary to know how much of total change is due to accepting past laws’ built-in growth and how much to new legislation.

My goal is simply to focus first and foremost on those numbers that provide transparency and promote accountability. Current ways of budget reporting do neither. And the resulting confusion hides the real harm caused by a budget that adapts inadequately to our most pressing needs.