Big, Small or Working Government

Posted: February 11, 2009 Filed under: Columns, Taxes and Budget Leave a comment »The question we ask today is not whether our government is too big or too small, but whether it works.

—President Barack Obama, Inaugural Address, January 20, 2009

In his inaugural speech, President Obama attempted to move beyond the partisan divide over size of government, claiming that his tenure would be mainly devoted to making government work. Some might view this statement simply as a political appeal to moderates in both parties—echoing President Clinton’s 1996 election year claim that “the era of big government is over.” Others more cynically might view it as a ploy to get around the dilemma that plagues almost every winning candidate when campaign promises for both tax cuts and spending increases face the reality of governing.

I view the statement simply as one driven by arithmetic. Making government “work” has now become the primary task of elected officials and the main way that they find the resources necessary to do new and better things. Failure to recognize this simple arithmetic fact has stagnated government progress for decades.

Over the past 50 years, the federal government’s revenues have averaged 18 ½ percent of our gross domestic product (GDP), and spending has averaged closer to 20 percent. During that time our Presidents and Congresses have seesawed back and forth between enacting tax cuts and tax increases. In the past 20 years, policy debates on taxes, although extremely intense, largely focused on whether the top income tax rate should be around 35 or 40 percent—as if that defined whether government worked. But this debate has become sterile and given far too much priority relative to whether our educational, social welfare, old age, health, and tax systems serve us well. Notably, President Obama’s successful electoral appeal seems to have rested less on his positions in this somewhat old debate and more on his suggestions that in transforming government he would move beyond it.

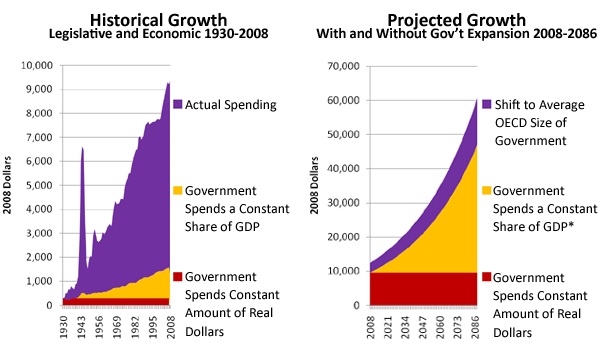

Let’s compare the period since 1930—which entailed large growth in the size of government relative to the size of the economy—with some future date where the U.S. government grows to the higher average level among developed economies, mainly Western Europe, or perhaps shrinks by an equivalent amount. The math is unmistakable: in determining what resources are available to finance needs in the future, government growth relative to the size of the economy will no longer be a dominant factor in sustaining growth in spending. On the other hand, more than ever, most new resources that government will spend will depend upon economic growth, regardless of whether government’s share of the economy grows or declines by a few percent.

Since 1930, the federal government’s spending as a share of the economy increased six-fold—from about 3 ½ percent of GDP to around 20 percent today. It vastly expanded its reach far beyond what it could have done by taking the same share of the pie and then depending upon economic growth alone. Today, however, the debate is not over whether to enact increases in average spending or tax rates by another six-fold (to 120 percent!). Instead, it centers largely on whether we emulate higher Western European levels of spending and taxation, stop somewhere between their levels and our current levels, stay where we are, or drop a few percentage points.

Consider the limits on how far economic growth by itself could have taken government spending in 1930 if government was the same size as it is now. The income of Americans did expand about six-fold after the early 1930s, making possible a six-fold increase in government spending even if the government only absorbed the same share of the total economic pie. But six times a number close to zero is still much closer to zero. Put another way, economic growth builds on a much larger level of government today than in the past.

The figure below compares the growth in spending made possible by economic growth versus government growth, both historically and under a presumed jump by about six percentage points of gross domestic product. The future of making government “work,” the data demonstrates, is today dominated by figuring out how to make best use of the additional revenues that economic growth naturally creates. Indeed, the graph understates the potential effect of economic growth, since bad spending and tax policies can undermine this growth.

President Obama is not the first President of the 21st century, but if he delivers on his promise to focus on making government work, he will be the first to move the center of the debate from stale 20th century fights to core 21st century issues.

Real Per Capita Spending

*Assumes 2% real per capita GDP growth, based on the average historical rate from 1977 to 2007. Note: Current and projected government spending excludes the currently debated stimulus package. Source: Gene Steuerle and Tim Roeper. Authors’ estimates, based on the Budget of the U.S. Government FY 2009 and past years and the U.S. Census.