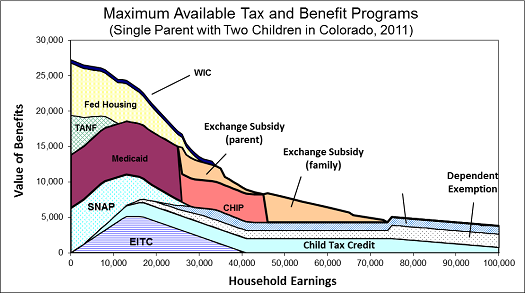

How Earnings Affect Benefits for Households with Children: The Extreme Welfare Case

Posted: November 1, 2012 Filed under: Children, Income and Wealth, Shorts, Taxes and Budget 4 Comments »In theory, a household may be eligible for a broad range of government supports. Some are universally available, such as earned income tax credits and SNAP (formerly called food stamps) to a household with children if earnings are low enough. (See a previous short on this subject.) Others are only available to some people. For instance, government establishes waiting lists for programs like rental housing subsidies and limits number of years of participation in the traditional welfare program, now called Temporary Assistance to Needy Families or TANF.

The figure below assumes a single parent with two children is receiving almost all these benefits, an extreme case. It includes the more universally available programs, like SNAP. It also assumes the availability of the new Exchange subsidy provided by health reform. Benefits add up to close to $27,000 when this household fails to work and fall to about $8,000 as earnings increase to $40,000. Note that the graph does not take into account free child care support or income and Social Security taxes. When these are added to other benefit reductions, the household can sometimes even lose net income by earning more.

For further detail see my testimony before the House Subcommittees on Human Resources and Select Revenue Measures on June 27, 2012, “Marginal Tax Rates, Work, and the Nation’s Real Tax System.”

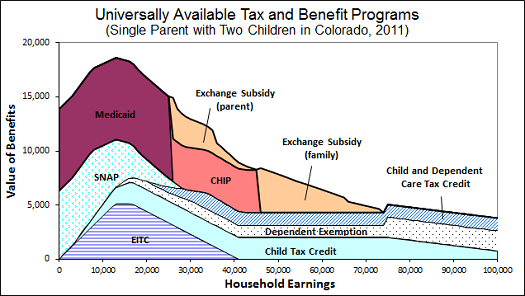

How Earnings Affect Benefits for Households with Children: The More Universal Case

Posted: October 31, 2012 Filed under: Children, Income and Wealth, Shorts, Taxes and Budget 5 Comments »Many government programs automatically grant eligibility to all families with children, depending only on their income. As their incomes increase, however, these families often, but not always, receive fewer benefits. Some restrictions operate on a schedule: earn $1 more, get 30 cents less in benefits. Medicaid provides eligibility up to a given income level, then denies eligibility when one more dollar is earned (though usually with a delay). The dependent exemption only is available to those owing taxes, and only at high income levels is removed by the alternative minimum tax.

How do these programs interact?

The figure below considers a single parent household with children and shows how these various benefits vary as the earnings of the household increase. Because every household with children, including you and me if we are raising children, is eligible for these programs if our income falls in the right ranges, we can be said to belong to this benefit and benefit reduction system. For instance, as income increases from $10,000 to $40,000, our household would lose most earned income tax credits, SNAP (formerly known as food stamps), and much Medicaid, though under health reform other health subsidies would still be available. Note that in addition to these losses of benefits, direct tax rates from income and Social Security taxes would apply, though they are not shown here. For further detail see my testimony before the House Subcommittees on Human Resources and Select Revenue Measures on June 27, 2012, “Marginal Tax Rates, Work, and the Nation’s Real Tax System.” My next short describes the extreme welfare case.

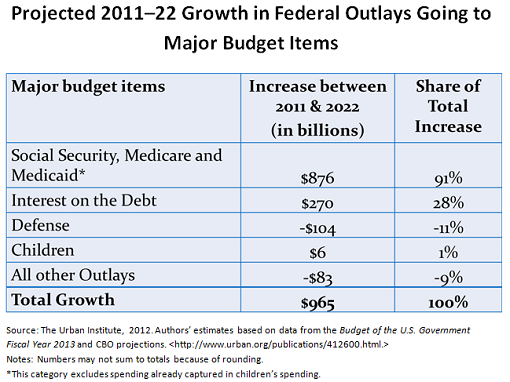

The Budget Crunch for Children—An Update

Posted: July 19, 2012 Filed under: Children, Columns, Taxes and Budget 1 Comment »The Urban Institute recently released Kids’ Share 2012: Report on Federal Expenditures on Children through 2011, by Julia Isaacs, Katherine Toran, Heather Hahn, Karina Fortuny, and myself. It looks comprehensively at trends in federal spending and tax expenditures on children over the past 50 years. This sixth annual report is well worth a look if you are at all interested in how children fare in the federal budget.

In 2011, federal outlays on children fell by $2 billion, dropping from $378 billion in 2010 to $376 billion in 2011. This is the first time spending on children has fallen since the early 1980s.

However, children’s share of the spending has gone up and down over the last fifty years. Federal budget outlays on children as a percent of the domestic budget have declined from 20 percent in 1960 to 15 percent in 2011. Spending on children has not kept pace with growth in government spending over the last fifty years.

In the future, spending on children is expected to further decline, driven by budget pressures, which are strongest on the very types of programs on which kids rely: domestic discretionary programs like education that, unlike entitlements, do not grow automatically but require congressional funding each year. From 2011 to 2022, federal outlays are projected to grow by almost $1 trillion, but children gain almost nothing from this growth. In comparison, the nonchild portions of Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are projected to claim 91 percent of the increase.

As a result, children’s spending is projected to fall sharply as a share of the economy, from 2.5 percent of GDP in 2011 to 1.9 percent in 2022, below pre-recession levels. In 2017, Washington will start spending more on interest payments than on children.

Future decreased investment in children can be compared to increased investment on seniors. Their starting points are also different: in per-person terms in 2008, the federal government spent $3,822 on children and $26,355 on the elderly (in 2011 dollars). Take into account state and local spending, and a child on average still only gets about 45 percent as much as an elderly person.

The decrease in emphasis on children is part of a broader worrying trend that increasingly crimps investment, budgetary flexibility, and choices for the future.

Testimony on Drivers of Intergenerational Mobility and the Tax Code

Posted: July 10, 2012 Filed under: Children, Income and Wealth, Shorts, Taxes and Budget 2 Comments »On July 10, 2012, I testified before the Senate Finance Committee on “Mobility, the Tax System, and Budget for a Declining Nation,” available online here. Below is a shorter summary of my testimony.

Nothing so exemplifies the American Dream more than the possibility for each family to get ahead and, through hard work, advance from generation to generation.

Today mobility across generations is threatened by three aspect of current federal policy:

- a budget for a declining nation that promotes consumption ever more and investment, particularly in the young, ever less;

- relatively high disincentives to work and saving for those who try to move beyond poverty level income; and

- a budget that generally favors mobility for those with higher incomes, while promoting consumption but discouraging mobility for those with lower incomes.

Let me elaborate briefly.

First, in many ways, we have a budget for a declining nation.

Even if we would bring our budget barely to a state of sustainability—a goal we are far from reaching right now—we’re still left with a budget that allocates smaller shares of our tax subsidies and spending to children, and ever-larger shares to consumption rather than investment.

Right now the federal government is on track to spend about $1 trillion more annually in about a decade. Yet federal government programs that might promote mobility, such as education and job subsidies or programs for children, would get nary a dime. Right now, these relative choices are reflected in both Democratic and Republican budgets.

Second, consider that one of the main ways that part of the population rises in status relative to others is by working harder and saving a higher portion of the returns on its wealth. Discouraging such efforts can reduce the extent of intergenerational mobility.

One way to look at the disincentives facing lower-income households is to consider the effective tax rates they face, both from the direct tax system and from phasing out benefits from social welfare programs. After reaching about a poverty level income, these low- to moderate-income households often face marginal tax rates of about 50 or 60 percent or even 80 percent when they earn an additional dollar of income.

Third, in a study I led for the Pew Economic Mobility Project, we concluded that a sizable slice of federal funds—about $746 billion or $7,000 per household in 2006—did go to programs that arguably try to promote mobility. Unfortunately 72 percent of this total comes mainly through programs such as tax subsidies for homeownership and other saving incentives that flow mainly to middle- and higher-income households. Moreover, some of these programs inflate key asset prices such as home prices. That puts these assets further out of reach for poor or lower-middle-income households, or young people who are just starting their careers. Thus, programs not only neglect the less well-off, they undermine their mobility.

Finally, a note about some current opportunities. Outside education and early childhood health, if Congress wishes to promote mobility of lower-income households, as well as protect the past gains of moderate- and middle-income households that are now threatened, almost nothing succeeds more than putting them onto a path of increasing ownership of financial and physical capital that can carry forward from generation to generation.

Two opportunities, largely neglected in today’s policy debates, may be sitting at our feet.

First, rents have now moved above homeownership costs in many parts of the country. Unfortunately, we seem to have adopted a buy high, sell (or don’t buy) low homeownership policy for low- and moderate-income households.

Second, pension reform is a natural accompaniment and add-on to the inevitable Social Security reform that is around the corner.

I hope you will give some consideration to these two opportunities.

In conclusion, the hard future ahead for programs that help children, invest in our future, and promote mobility for low- and moderate-income households does not necessarily reflect the aspirations of our people or of either political party.

“Investment” and Obama’s First Budget

Posted: January 6, 2009 Filed under: Children, Columns, Economic Growth and Productivity, Income and Wealth, Taxes and Budget Leave a comment »President-elect Obama’s chief in-house economic advisor Larry Summers suggests in a recent Washington Post piece that the new Administration will put a lot of effort into addressing long-term growth challenges, not just short-term policies that generate consumer spending. How? Through “investments.” To make sure we get the point, Summers uses that word or some variation 12 times.

But the first Obama budget will not be oriented toward investment. Just as with recent administrations, the words will stress “investment” but the numbers will emphasize “consumption”—not only in the short-term but, more dangerously, in the long-term. In fairness, this is the budget the new administration inherits. They gain control of the wheel of a battleship sailing full-steam ahead toward the icebergs. But by using terms like “down payment” to describe new proposals, Summers hints that no major course correction will be sought.

Consider first the short-term. If, by the time the recession is over, the government takes on net additional liabilities of, say, $2 trillion and invests even as much as one-fourth of that amount, then its net investment is minus $1.5 trillion. And that assumes that the investments really are investments. Believe me, politicians will now be calling every item they favor, even the subsidized importation of tsetse flies, an “investment.”

I’m not suggesting that a faster economic recovery, if achieved, could not bring enormous benefits, eventually including higher private investment and higher government revenues. But regardless of Summers’ pitch for investment, the means toward that end still rests primarily on financing additional consumption through higher debt.

So the real issue is the long term. If we consume more temporarily as a means of recovering our economic health while moving toward a path of long-term investment, it’s one thing. If we’re planning on only increasing our consumption even further down the road, it’s another.

Recently, I led a study sponsored by the Partnership for America’s Economic Success that comprehensively examined total investment policies by the federal government (see http://www.urban.org/UploadedPDF/411539_investing_in_children.pdf). While we paid special attention to investments in children because of their extraordinary long-term importance and potential high rates of return, we nonetheless reviewed all types of investment. Because researchers disagree on exactly how to measure investment, especially if counting some forms of social spending, we also used a variety of measures.

No matter how we parsed the numbers, the message was clear: relative to GDP or domestic spending, total federal investment and investment in children fell over the past few decades. More importantly, overall government investment, and especially investment in children, is declining in relative and sometimes absolute importance.

The cause of the problem: these potential investments are being squeezed out mainly by faster, automatically growing programs that tend to favor consumption. For instance, while growth in the economy would provide some additional $650 billion in additional domestic spending annually by 2017, the amount going toward education and research would be about zero under current law. Alternatively, the share going toward kids’ education and research and work supports for families with children and social supports for children would be only about $26 billion, and that number is weakly positive only because of bad news: constantly growing health costs.

Unlike the one-time costs of dealing with a recession, such large numbers would repeat over and over again at ever higher levels each succeeding year. For almost all purposes, including investment, how we spend hundreds of billions and eventually trillions of dollars of additional revenues year after year swamps in importance how well we allocate stimulus spending meant to be temporary.

Despite several mentions of the long term and a few mentions of children, Summers did not really intend for his Washington Post piece to set out the long-term policies of the Obama administration. He was more narrowly addressing an ongoing debate, primarily among Democrats, about how to spend new stimulus money made available today. Should we aim only to get money out to people as quickly as possible to stimulate their demand and consumption? Or should we determine that if we are going to spend so much money, we ought to get something back for it in the form of “investment.” That Summers published the piece tells us that his side won the internal debate within the Obama camp.

The issue for many of us is not just about whether we do a little maintenance on the side while we fix the battleship’s leaking hull. The ship is still heading in the wrong direction—not without potential consequences for both the hull and the battleship as a whole.

An Issue of Democracy

Posted: June 23, 2008 Filed under: Children, Columns, Income and Wealth, Taxes and Budget Leave a comment »I know. It’s campaign time. Time for our politicians to promise us more and more. Of course, it is always someone else who will pick up the tab. Senator Russell Long’s famous quip still holds: “Don’t tax you. Don’t tax me. Tax the man behind the tree.”

Today “the man” is increasingly the young, who are not only asked to pay more for others and get less for themselves, but who are increasingly being denied their fundamental democratic rights to share equally in deciding just what type of government we should have.

In normal times, additional promises at election time would be okay, even proper. Many of our government institutions—including the tax structure and health subsidies—do need fixing, and the country should have an open debate about how. But these aren’t normal times.

The mantra of both Republicans and Democrats today is that no politician can win office by being totally honest about the balance sheet—those spending cuts and tax increases required to pay not just for their new spending increases and tax cut proposals, but all those promises arising from past legislation.

Oh, the Democrats tell us they will tax the rich a bit more, and the Republicans tell us they will eliminate waste. But, in truth, the middle class is so large that it mainly pays for whatever promises do materialize.

The threat is not simply to the economy. Today, our fundamental democratic institutions are threatened in a very new way. While it has become increasingly difficult to deny the vote de jure on the basis of property, gender, or race, our laws now discriminate de facto against the young.

At its core, democracy is about equal rights to vote—and have your representatives vote—on the nation’s current priorities. But many recent laws attempt to deny us—and, even more so, our children—the opportunity to determine those priorities.

The reason is simple, but its effects are profound. Never before in U.S. history have so many promises been made to so many people for so many years into the future. Every additional promise, no matter what its merit, only attempts to tie that fiscal straightjacket tighter around future voters.

If our tax laws merely stay the same from 2006 to 2010, for instance, government revenues would rise by several hundred billion dollars. But guess what? Most of those revenue increases are already committed, mainly to the growing costs of our current health and retirement programs.

It gets worse. In a little more than a decade, we’ll likely have around $1 trillion more in annual revenues, yet under current law almost all of that growth will have been pre-allocated without so much as a nod from the existing or future Congresses.

Until those issues are dealt with up front, new promises by our presidential candidates are largely puffs in the wind.

Do you believe we should spend more on health care for the nonelderly? Sorry, nothing left for that. Help the elderly poor or those in their last years of life? Sorry, we’ve already promised an increasing share of revenues to younger and healthier seniors. How about tax cuts to restrain government growth? Sorry, tax revenues won’t even cover the promises already on record. Spend a little to fix our educational system? Give me a break. The share of spending on children is already scheduled to decline to help pay for an even larger share for groups already getting the lion’s share of government spending.

To be clear, the issue here is not whether political promises are for things silly or sane. U.S. history is replete with gut-wrenching and nation-changing debates on how government should wield its tax and spending powers. Those who defended Henry Clay’s “American System” believed in expanding public works into ever-more territories. Those opposing Clay considered this form of spending corrupt and objected to the tariffs used to finance them.

Jumping forward about a century, most of Franklin Roosevelt’s Depression-era spending priorities aimed to help Americans get jobs and to help support the unemployed. Families who weathered that longest of downturns have been forever grateful as a result. Many family histories, including mine, include stories of relatives who got public service jobs that tided them over.

Economists see it differently, crediting better monetary and fiscal policy, largely following the war effort, for ending the Depression.

Still, in most of the 200-plus years since the American republic was founded, most spending and tax debates were over projects of the day. They weren’t about controlling what government priorities would be in 50 years. Whether worthwhile or horrible, precedent-setting or routine, new laws and programs weren’t designed to predetermine government’s direction for decades to come.

Given the fix we’re in now, the debate over taxing and spending will not and should not end. The crux of the debates from here on out must be distinguishing between laws written for today and mandates for tomorrow. Saddling distant tomorrows with growing commitments forecloses other potential uses of the revenues that come with a growing economy. It takes democracy out of the hands of citizens, especially the young, who can be counted on to rebel—as some already are—against paying for priorities they didn’t help pick.

Crumbs for Children?

Posted: April 4, 2007 Filed under: Children, Columns, Taxes and Budget Leave a comment »Kids are a priority in almost every family’s budget. From the moment we hold our newborns in our arms, feeding, clothing, housing and educating them trumps everything else. But in the federal budget, the reverse is true: only a modest fraction of federal spending is aimed at kids. And that fraction is scheduled to decline because neither political party is willing to fix what it knows is plaguing our spending and tax systems.

With my Urban Institute colleagues, I’ve been tracking federal spending and investment in children for two projects-First Focus and Partnership for America’s Economic Success. We’ve looked at budget trends and patterns since 1960 and, based on current law, projected them forward to 2017.

The bottom line is that kids have never batted first in the budget. In 1960, when defense still took about one-half of the budget pie, the kids’ share of the remaining domestic budget was at best about 20 percent. Between 1960 and 2006, the domestic budget pie grew significantly, largely because of economic growth and the decline in the share garnered by defense, but children got only about 15 percent of the additional filling. Now, we’ve put into law so many other growing commitments that the kids’ share of the additional filling is projected to shrink to less than 6 percent by 2017.

In dollar terms, children’s programs under laws now on the books would gain only $36 billion in a little more than a decade, even while other domestic programs would expand by $609 billion. Adopt the programs put forward by our Republican President or advocated by many Democrats in Congress, and the figures change only slightly. Exclude their share of the growth in Medicaid costs, and kids get just about nothing.

Even though their position is eroding, children are the apples of some programs’ eyes. More than 100 federal spending programs aim to improve the lives of children through cash assistance, health care, food and nutritional aid, housing, education, and training. At one time, the average-income working families with children paid almost no income or Social Security tax. Those days are gone, though recently some new credits (like the child credit) have helped put such families on more solid financial ground.

Let’s see what’s driving the projections. Economic growth is likely to deliver roughly 35 percent more revenues by 2017 than it does today. Most of this will finance additional domestic spending even if some goes to chip away deficits and even if we’re still spending the same share of the budget on defense and foreign policy. Retirement and health will get much bigger shares of the budget pie, and, as their shares grow, arithmetic tells us that others must decline. Children’s programs are among those hardest hit-getting smaller percentage shares and often even less filling than they have had in the past. The one exception to this tale of contraction is not necessarily good news. The children’s health budget, although only a sliver of the total health budget, will grow under current law as long as overall health costs keep rising. Rising costs, however, induce more families to stop purchasing insurance, so the net gains for children are limited.

Kids also bear the brunt of another ominous budget trend: larger shares of federal money going to consumption and smaller shares to investment, including investment in children. So far, none of the growing field of Republican and Democratic presidential hopefuls is kindling much hope for a change in priorities. Not one has said much about curbing growth in the ravenous retirement and health programs, even though more investment-oriented programs are starving as a result. There are murmurs about allowing some tax increases, but mainly to stem deficit growth. These clearly would not do more than temporarily reverse the decline, much less nourish and prepare the next generation.

Our skewed priorities defy reason as well as fairness. As the kids’ share of the budget shrinks and we invest in them proportionately less, how can we expect them later to earn the money to pay the taxes to cover our ballooning pile of retirement and health benefits? Think about it: we’ve put into the law that they owe us ever more and we owe them ever less.

It’s time now to focus on what we can do for kids. Investment—particularly in children—needs to become the budget priority. But kids will take a back seat until we’re honest enough to admit that the priority now is to spend more and more on ourselves, while leaving the costs to them. Don’t they deserve better?