Thanks, Boston, for Restoring My Faith

Posted: June 1, 2016 Filed under: Columns 2 Comments »Like many others, I have found it difficult to maintain a sense of optimism this campaign season. I’m less anxious about the candidates, whatever their limitations, than about how much we, the public, seem to tolerate—even at times support—campaigns whose modus operandi focuses on attacking others, whether other candidates, parties, or populations other than our own. I always worry when any of us (including myself) seeks an enemy on which to re-anchor a threatened political or religious belief or simply project discontent. At a minimum, this way of tackling our problems retards progress by failing to focus on what we can do together. More dangerously, it portends either disintegration or authoritarianism when it arises in decent times or periods of limited growth, thereby gaining potential to explode in times of true distress. If you want evidence, just look at the retreat from democracy in some developed nations throughout the 20th century or today in Turkey, Hungary, and, potentially, Austria and parts of Western Europe.

A day at the Boston marathon more than took away my gloom. I went there to cheer on my stepdaughter and a friend with whom I have worked at an Alexandria community foundation. It wasn’t just their fortitude and courage, as well as the efforts of thousands of other runners, that inspired me. My faith in humanity was restored by the extraordinary support of the public. There they were by the hundreds of thousands, from one end of the course to the other, cheering on everyone who passed by.

There were no class divisions for whom the bystanders cheered; everyone was a hero for trying. The runners ranged from the world’s best to those who barely had the stamina and body parts to survive—or maybe that’s my own projection of what I would look like out there. When the mobility impaired ran by, the cheers got even louder. No one was a stranger. Each public cheerleader only competed to see who could be loudest and support the most runners. Local bands found a street corner on which to play. Businesses gave out ice cream and other free goodies. Conversations flourished among absolute strangers. One of my companions broke into tears witnessing the community response.

Survivors of the 2013 terrorist attack also ran, making clear that fear—the only thing that can make terrorism succeed—would not deter them. Ken Ballen, the brilliant president of Terror Free Tomorrow, has long stressed that terrorists need a community to thrive or even survive. Such communities can form around, or in response to, blaming or distrusting others; they disconnect from the people and communities around them that don’t share their views. They are the exact opposite of what I observed of Boston that day. Thus, despite the very real pain in Boston, as well as San Bernardino, Fort Hood, Charleston, and other parts of the country attacked by individual terrorists or fanatics, our nation still thrives because of the strength and resilience of our communities.

So thank you, Boston. Your actions do more than inspire me. They drive me to undertake actions that include, unite, and ultimately strengthen the communities in which I work, play, and live. Whatever happens in the remaining campaign season, I can only pray that our leaders, whether newly elected or reelected, will learn from and follow your lead.

What the Success of Trump and Clinton Portends for Future Elections

Posted: May 24, 2016 Filed under: Columns Leave a comment »Despite their divergent policy views, Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump have many similarities that help explain their success in this election season. Pay attention: these lessons will be taken up, for better or worse, by future candidates seeking office in an unreformed system and by those in Congress, the states, or the political parties seeking reform after viewing with disdain the 2016 primary election process. With one exception, I list these common attributes in what I consider their rough order of importance to this and future campaigns: initial fame, use of identity politics through appeal to an excluded group, wealth, Ivy League pedigree, New York connections, presidential campaign experience, a sense of entitlement, and birth year.

- Fame. From the beginning, Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton were the most famous candidates in their respective parties, even before the media facilitated Trump’s further rise by granting him an extraordinary share of the attention. Correspondingly, the weakest candidates also tended to be the least famous. Initial fame has usually been quite important to both parties, though a bit less so on the Democratic side, where the Jimmy Carters and Barack Obamas have been able to build upon their appeals as outsiders. More unusually this time around, it didn’t seem to matter much where the fame came from, thus following the saw of our increasingly media-crazed world that bad publicity is better than none at all.

- Identity politics and appeal to an excluded group. Clinton and Trump—along with Cruz and Sanders—built their campaigns on a base of vocal supporters who felt underrepresented and denied a fair voice in government: liberal older women, men without college degrees or with declining job prospects, evangelicals, and the young. Yes, each of these groups is diverse, but each provided a surge in voters for the primaries as well as enthusiastic volunteers for the campaign trudge. The same might be said eight years ago about President Obama’s appeal to liberals of all colors who felt that his election would help complete a civil rights revolution. This pattern amends the traditional notion that the excluded group to whom one must appeal is the far left or far right of each party, or as Richard Nixon told Bob Dole, “You have to run as far as you can to the right because that’s where 40 percent of the people who decide the nomination are. And to get elected you have to run as fast as you can back to the middle.” With declining party identity, by the time of the general election the majority of the public now identifies with neither party nor that excluded group successful in the primaries. Themselves now largely excluded unless new coalitions can be formed, they will decide the final election by whom they vote against rather than for.

- Wealth. The Clintons are worth at least $50 million and perhaps more than $100 million. While Trump has been accused of exaggerating his net worth, it is plentiful enough. Or, as he told Good Morning America in 2011: “That’s one of the nice things. I mean, part of the beauty of me is that I’m very rich. So if I need $600 million, I can put $600 million myself. That’s a huge advantage. I must tell you, that’s a huge advantage over the other candidates.”

- Ivy League credentials. Hillary Clinton has degrees from Wellesley (one of the “little Ivys”) and Yale. Trump got his bachelor’s degree from the University of Pennsylvania. Cruz was educated at Princeton and Harvard, and Sanders received his degree from the University of Chicago. This trend isn’t new: Obama graduated from Columbia and Harvard, George W. Bush from Yale and Harvard, Bill Clinton from Oxford and Yale, and George H.W. Bush from Yale. All recent Supreme Court justices are Yale or Harvard Law School graduates. Don’t be fooled by stories about the declining power of old boy and old girl networks, or by tales that a strong education advances worldly fame or success, at least at the top of the pyramid, more than where you go to college, graduate school, or law school.

- New York connections. More money and more connections. Trump, a New York real estate magnate, and Clinton, a senator from New York, have been able to build upon their geographical connections to finance and wealth. All Republican presidents from Hoover onward, apart from war hero Eisenhower, have been from the big, moneyed states of California, New York, or Texas. Add Massachusetts to the list, and both parties have usually had a major candidate, if not actual nominee, from one of those four states for the past 80-some years. (Cruz, of course, is from Texas.) Bigger states also add to fame and electoral votes, not just money and connections.

- Presidential campaign experience. Everyone remembers that Clinton ran before, but you might not remember that Trump floated the idea of running in 1988, 2004, and 2012; in 2000, he won two primaries under Ross Perot’s Reform Party banner. Of course, here we have nothing new. Many presidents—including Kennedy, Johnson, Nixon, and both Bushes—previously ran for president or vice president or knew what to do from participating in their fathers’ efforts.

- A sense of destiny. Both major party candidates feel like they have worked hard and paid their dues, that others are conspiring to deny them something they have earned, and that they personally must acquire power to fight for our rights. Perhaps this is a requirement for anyone running for president.

- Birth year 1946-47. Malcolm Gladwell has commented on the power of small cohorts, ranging from late 19th-century industrial monopolists to leaders of the IT revolution, to dominate many thrusts forward. Consider, then, some birth years: Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, and Donald Trump, 1946; Hillary Clinton, 1947. Maybe this is the JFK factor: the excitement of the Kennedy-Nixon election and the resulting attraction to politics of those in late adolescence in 1960. But whether a random event or not, soon we will likely have 20 to 24 years of the presidency held by people born within either a 2- or 14-month period. Perhaps less repeatable than other attributes noted above. Or is it? Twenty-one senators were born between 1944 and 1950.

Opportunity for All Isn’t Gonna Happen on This Path

Posted: May 17, 2016 Filed under: Columns, Income and Wealth, Taxes and Budget 1 Comment »Over the past 30 or 35 years, income and government spending per household have both about doubled, but working- and middle-class Americans have seen much less improvement in their earnings, wealth, education, and skills than they did in earlier decades. The international economy and the concentration of power within the top 1 percent are major factors, but it’s hard to believe that we can’t do a lot better with the $60,000 in federal and state spending and tax subsidies we spend annually per household, or the $2 million in health, retirement, education, and other direct supports scheduled for each child born today. My recent study finds that the US budget is moving increasingly away from promoting opportunity for all.

At the same time, Hillary Clinton, Donald Trump, and almost everyone running for office ascribe to the notion of America as a land of opportunity while telling supporters they are being denied the opportunities owed them. But it takes more than rhetoric to climb out of our current political pit.

In the study I draw three major conclusions:

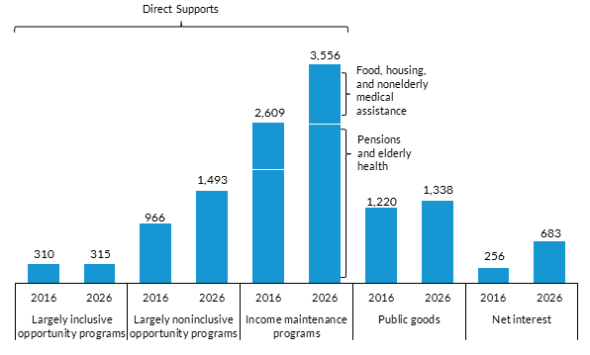

- First, the few programs that attempt to promote opportunity, such as work incentives and education, are scheduled to take a smaller share of available federal government resources. There is one major exception: large tax subsidies for housing and for employee benefits like retirement accounts continue to expand. However, by largely excluding low- to middle-income households, those programs show how today’s programs largely fail to promote opportunity for all. That is, they are not inclusive opportunity programs. Figure 1 summarizes these results.

- Second, if we wish to promote opportunity for all, we must carefully discern the outcomes pursued and judiciously measure how well programs achieve those outcomes. “Opportunity for all,” if left amorphous, lacks any prescriptive power, leads to claims that anything the government does or stops doing can promote opportunity, and, as long as the intended outcomes are unspecified, prevents assessing program performance. I suggest that opportunity for all is not simply an equity objective: it pursues outcomes centered on growth over time in earnings, employment, human and social capital, and wealth while it emphasizes inclusion, especially of low- and middle-income households. And I suggest that we can and should measure most programs by their performance on that opportunity standard, even if the primary standard by which they are judged—such as retirement, food security, or even defense—seems initially removed from that opportunity focus.

- Third, there’s tremendous budgetary potential for promoting opportunity whether the government increases or decreases relative to the economy. Realizing this potential doesn’t require moving backward on other fronts but shifting tracks, as from north to northeast, to also move forward on the opportunity front. The trick is to channel a larger share of the additional revenues provided by economic growth toward an opportunity agenda. Ten years from now annual federal spending and tax subsidies are scheduled to increase some $2 trillion (or roughly $15,000 per household), but essentially none of that growth goes to opportunity-for-all programs. Children receive almost nothing a decade hence, while interest on the debt rises significantly because we are unwilling to collect enough taxes to pay our bills as we go along.

When you look at these numbers, it seems clear that reorienting budget priorities could help provide opportunity in ways likely to promote equality in earnings and wealth. What is also clear, however, is that small ball is not going to get the job done when so much in the budget is moving in the direction of deform, not reform.

Figure 1

Total Outlays and Tax Expenditures for Major Budget Categories under Current Law

Billions of 2016 dollars

Source: Author’s tabulations of Congressional Budget Office data.

Notes: Public goods include such items as defense, infrastructure, and research and development that benefit the population broadly. Direct supports are programs and transfers that directly benefit households and communities, such as health care and education. Within direct supports, income maintenance programs such as Social Security, Medicare, and SNAP (formerly food stamps) protect a certain level of income and consumption, while opportunity programs aim to increase private earnings, wealth, and human capital over time. Largely inclusive opportunity programs benefit low- and middle-income groups, while noninclusive opportunity programs largely exclude them or provide them with fewer supports than upper-income groups.

EITC Expansion Backed By Obama and Ryan Could Penalize Marriage For Many Low-Income Workers

Posted: April 5, 2016 Filed under: Columns, Income and Wealth, Taxes and Budget 3 Comments »President Barack Obama and Speaker Paul Ryan have proposed similar expansions of the earned income tax credit (EITC) for low-income workers without children. Their goal is laudable: to provide some modest additional income support for low-income workers currently excluded from the EITC. But as designed, their proposals would penalize many low-income workers who choose to marry or are married. Taking that step would not only provide a disincentive to marriage, it would be unfair to many married couples and erode support for the credit itself and for wage subsidies more broadly.

Fortunately, they can fix this flawed design by splitting credits for low-wage workers and benefits for children. Before I explain how, here is a bit of background.

The EITC, enacted first in 1975 under President Gerald Ford, has been expanded under every succeeding president and has broad bipartisan support. As cash welfare programs like Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) and its replacement, Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF), have shrunk as a share of both the economy and the budget, the EITC has become a bedrock of the nation’s social welfare structure and the largest government cash support for those neither retired nor disabled.

About 97 percent of EITC benefits, however, go to households with children, particularly single parent families. The very small sliver going to single individuals through the so-called “childless worker” credit is limited by a maximum of less than $600 and is completely phased out at less than $15,000 of income, or less than what would be earned at a full-time minimum wage job. By contrast, the EITC can provide close to $6,300 in 2016 for a single parent with three children and is available to families with up to $48,000 of income ($53,000 in the case of married couples).

Obama and Ryan would double the childless worker credit and increase the income levels at which it phases out. A similar though higher level of credit was provided by the Paycheck Plus Project in New York City, which offers some individuals up to $2,000 and even allows a modest credit for those making up to $30,000.

There’s a glitch in these proposals, however, and it’s a big one. For instance, one report suggests that Paycheck Plus provides “more generous support to all low-income workers.” But in reality it doesn’t. Many low-wage workers who marry into families not only lose their own childless worker credit, but also reduce the normal credit available to their partner with children.

Here’s one example of how they lose out. A childless male making $11,000 qualifies for a credit of $1,011 under the Obama-Ryan model in 2016. If he marries a spouse with two children making about $20,000 and getting a credit of $5,172, they would get only one credit of $4,018, a loss of $2,165 from the combined credits of $6,273 they had before marriage.

As a result, the credit Obama and Ryan both support would penalize many married couples, while encouraging low-income couples to delay marriage and household formation. Because these penalties would be quite transparent to millions of married couples filing their tax returns, they would likely erode support for the EITC in general.

There is an ongoing debate about how much a marriage penalty actually affects decisions to wed, but there is little doubt that avoiding marriage is THE tax shelter for low- and moderate-income individuals.

The problem can be fixed by separating credits for low-wage work and benefits for children. My Tax Policy Center colleague Elaine Maag and I have proposed this separation as a way to expand work supports for both groups largely left out now: the childless worker and low-wage workers who marry. As for the single head of household, her current credit would be replaced by two credits: one for households with children and an additional low wage worker credit based solely on earnings regardless of children. They’d phase in and out at roughly the same income levels and add up to roughly what she received under the old EITC.

Meanwhile, both the single person without children and the low-wage worker who marries into a family could get the new low-wage worker credit whether or not the family has children. Married couples with two low-wage workers would usually be better off, as now the addition of a worker to the household usually typically adds to rather than subtracts from total household credits received. Though we phase out the low-wage worker credit for those married to high wage workers, these are families for whom any EITC marriage penalty would be a smaller share of total income and who, at their income levels, largely benefit from marriage bonuses from other parts of the income tax rate structure.

The structure of any EITC is hard to summarize in a short column. The main takeaway is that the President and the Speaker could fix their proposals to do what they say they want—cover those low-wage workers now largely left out. And they could do it without penalizing those who vow commitment to their partners and their children.

This post originally appeared on TaxVox and UrbanWire.

What is Our Part in Making the Country Great Again?

Posted: January 19, 2016 Filed under: Columns, Taxes and Budget Leave a comment »Presidential campaign slogans often appeal to progress. Donald Trump’s has attempted to trademark “Make America Great Again,” claiming authorship of the same theme Ronald Reagan used in 1980. Barack Obama got great mileage in 2008 around his “Yes, We Can” theme. Compare on an optimism scale Franklin Roosevelt’s “Happy Days Are Here Again” with Herbert Hoover’s “We Are Turning the Corner,” and you can see one more reason Hoover lost that 1932 election.

Though I believe we should be optimistic about our future, these slogans, along with presidential campaigns more generally, pretend to offer one easy solution to thousands of very complicated problems. At their most basic, the slogans and campaign promises appeal to the notion that if we elect the right president, then progress, greatness and happiness will follow right behind. And, if our candidate is elected, we can feel really good about our achievement: we’ve won the Super Bowl of politics.

By simply choosing between candidate A and B, suddenly we can solve not just how to administer thousands of programs that together spend close to $4 trillion a year, but how to improve economic growth; address social ills; stop international terrorism; deal with worldwide economic, social, and military forces that lead to mass migration—or at least stop them from spilling over our borders; pay people to retire for one-third of their adult lives; make sure that households don’t have to pay more than $5,000 for the $24,000 worth of health care they now receive on average; keep taxes low and debt sustainable; and, of course, regulate the environment, occupational safety, and the financial industry, among others.

But where do we fit in? Do we solve the country’s problems by increasing our benefits from some government programs? By lowering our taxes? That’s what the campaigns tell us. We’re going to get more from or pay less to government AND make the world a better place along the way. Gosh, we’re good.

Identify, if you will, one candidate for president or Congress who doesn’t tell at least 90 percent of us that we are about to get something more from government if we elect her or him. Oh, a few might get less—you know, those lazy people on welfare or those rich tax avoiders who aren’t going to vote the same way as us anyway. Their losses will finance our gains, and $100 billion of higher taxes or lower benefits for a few will somehow cover $1 trillion worth of lower taxes (or higher benefits) for us.

The one-vote-solves-all mantra adds to our sense of dependence and incapacity to make the world better. What does it matter if we work harder or tutor or in other ways provide services and goods that others need? Why should we spend less on alcohol or fancy cars and donate the proceeds to some worthy cause when our contribution is just a drop into the bucket? Why should we fight terrorism by donating to the education of women in poorer countries when we can always send out more troops or bring them home, or raise others’ taxes or lower ours so the economy grows? Why should we gather in our community to address the social ills that threaten a significant portion of its children?

Why can’t others see the solution? We vote the right way, but they don’t; that’s why our problems aren’t solved. Sometimes we win, but then our successful candidate turns coat and fails to solve old problems while allowing new ones to arise. Or our favored son or daughter really tries when elected, but those others deny our democratically achieved victory from attaining its complete fulfillment.

It’s them again; it’s always them.

There is an alternative view. I firmly believe that what we are and what we achieve as a people derives from the sum total of what all of us do. Government can often help us combine our efforts, and, yes, government can block progress as well. Either way, it’s a damn poor excuse for our own failure to act well when we can and our tendency to blame others to excuse our own inaction.

So, yes, let’s engage fully in the elections. Let’s also be optimistic about the future when we live in a nation never so rich throughout all of history, and stand on the shoulders of those who went before us, who added to our store of knowledge, and sacrificed to make our own world a better place. At the end of the day, let’s also admit that progress derives from everyone’s efforts and reject wholeheartedly the dependency that derives from the notion that our role in advancing society comes mainly from flipping a toggle switch.

The Zuckerberg Charitable Pledge and Giving from One’s Wealth

Posted: January 11, 2016 Filed under: Columns, Nonprofits and Philanthropy, Taxes and Budget 2 Comments »Mark Zuckerberg and his wife, Priscilla Chan, recently pledged to donate 99 percent of their Facebook shares to charitable purposes over their lifetimes. They are doing it through the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, which uses a limited liability corporate structure.

Why not give to an IRS-approved charity, or a foundation created by Zuckerberg and Chan, instead? Two reasons leap to my mind, both shaped by nonprofit law. The first, which I fail to see in most commentary to date, is that generous lifetime giving by the wealthy can’t get much of a charitable deduction no matter how structured. Second, the Zuckerberg-Chan pledge falls into a class of efforts sometimes labeled “fourth sector” initiatives, which give much greater flexibility for how the money is used, including combining charitable and business purposes and lobbying for a favored cause—essentially what private individuals can but pure charities cannot do.

Economic Income, Realized Income, and the Charitable Deduction

In studies examining the behavior of those with significant wealth, other researchers and I show how little income they tend to realize, often 3 percent or less of the value of that wealth. That doesn’t mean the investors have earned such low rates of return. In fact, many like Mark Zuckerberg became millionaires or billionaires because they got very high returns. Most of their money, however, tends to be in stock or a closely-held business and, especially for those with only a few million dollars in total wealth, residences and vacation homes. As long as the wealthy don’t sell those assets, they won’t “realize” for tax or other accounting purposes the true economic returns or gains they achieve. And those gains can be substantially more than 3 percent: from 1926 to 2014, including during the Great Depression and Great Recession, stocks produced an average annual return of about 10 percent before inflation.

Related research examining the charitable activities of such wealthy individuals shows that most delay a huge portion of their giving until death. That is, they give from the wealth of their estates, not the income of their lifetimes. Why? Because tax law provides very little incentive to give huge donations to charity during a lifetime. Let’s suppose that Mark Zuckerberg and Priscilla Chan normally realize as income 2 percent of their estimated $45 billion wealth, or $900 million, this year. The charitable deduction is limited to 50 percent of yearly income, which in Zuckerberg and Chan’s case is $450 million; it’s only 30 percent ($270 million) if they want to give to foundation. Thus, if Zuckerberg and Chan give away more than 1 percent of their wealth each year, they run out of allowable charitable deductions. If in an average year they earn 10 percent on their wealth and give away only 1 percent, they are still accumulating much faster than they are giving it away, unless they consume billions annually.

Running out of charitable deductions doesn’t mean that the wealthy gain nothing from giving away money directly to charities earlier in life. Once assets are transferred to a charity, the donors don’t have to pay taxes on the income earned from those assets. But donors such as Zuckerberg and Chan would achieve only modest tax savings from early gifts to charity as long as their taxable income from the alternative remains a small percentage of their wealth. What also might be in play here, and I don’t fully know, is that the charitable side of the Chan Zuckerberg initiative will yield enough losses, transfers, and sales to needy individuals at below-market cost to offset any taxable income otherwise earned on the business side, so it can effectively avoid income tax just as well as an outright charity.

For Benefit Corporations and the Fourth Sector

So limits on the advantages of a charitable deduction provide a significant impetus for wealthy individuals to pledge money for charitable purposes without necessarily giving it to a charity. Donors may also think the flexibility they gain is substantial relative to any potentially modest tax costs. Giving to charity later is always an option, thus avoiding estate tax; meanwhile, other options haven’t been foreclosed.

Among the additional options at play is combining nonprofit and business activity. Among the many efforts of this type that get complicated in a pure charity setting are raising private equity; sharing real estate investment returns with low-income residents; running a business centered around training its workers and building up their equity rather than making profits for investors; investing in new drug research and pledging that the public, not investors, will garner any potential monopoly returns from some successful patent; or investing in green energy by granting some risk protection to private capital partners; and garnering research and development tax credits.

Some states have tried to create special rules applicable to certain “for-benefit corporations” that allow shareholders and charities to share returns. But, for the most part, the walls surrounding charitable money can’t be torn down. Federal and state tax and other nonprofit laws protect money that now essentially belongs to the public (with the charity as fiduciary), not to the donors.

If donors aren’t worried about getting a charitable deduction up front anyway, as is likely the case for Zuckerberg and Chan, the easiest route is to create a potentially profit-making limited-liability business. Meanwhile, donors can engage in all sorts of ventures without having their lawyers shouting “Stop” to each new creative idea because it might violate some charitable law. At the same time, Zuckerberg and Chan need a new entity since they can’t pursue their charitable pursuits directly through Facebook without soon running into problems meeting that corporation’s obligations to other shareholders.

If Zuckerberg and Chan decide that they want to lobby government, they also can avoid any limitation imposed on foundations or other charities.

These types of private initiatives, sometimes labeled as a Fourth Sector, push society in new, exciting, and yet-to-be-determined directions. As I’ve discovered when I raise money for charity, people will often consider giving away much more when asked to think about giving out of their wealth, not just their realized income. Fundraisers, take note: I don’t think we’ve even begun to tap this way of encouraging giving. Also, people often see new possibilities for enhancing charitable purposes when not confining themselves within the walls surrounding a typical charity, with entrepreneurs and venture capitalists often especially excited by the new adventure. Zuckerberg and Chan are merely two of the richer faces giving new attention to these broader movements.

My Christmas Wish List: I Want to Be a Drug Company

Posted: December 3, 2015 Filed under: Columns, Health and Health Policy, Taxes and Budget 3 Comments »When I was a kid, I asked Santa to bring me a bike or a baseball glove. As an adult, I mainly wished for good health and good cheer for myself and my loved ones. This year, I have a particular request that I hope the man in the red suit can grant: I want to be a drug company.

I want the government to give me a monopoly over what I produce. I want to be able to set almost any price for my products.

I want the government to pay for whatever tens of millions of government-subsidized customers buy from me. I also want the government to pay those who sell my product or spend their time advising and prescribing my product for others.

I want to be paid for years and decades for producing the same thing to meet some chronic need, even if it would be better to produce things that heal or cure. I want to be paid for things that sometimes turn out to be worthless, and to avoid the possibility of my customers haggling over prices or suing me because they don’t pay for those things directly.

I want Congress to give me the power to appropriate money to myself and give up some of the power reserved in the Constitution for itself.

But I’m not done.

I want the government to let me avoid paying tax on the income I earn from the money it pays me. I want to be able to live in the United States and claim citizenship for tax purposes abroad in some low–tax rate country. I want to defer taxes on my income, then have the government forgive that tax debt. And I want congressional representatives who for years—even decades—have been more interested in fighting among themselves than in doing anything about this type of arrangement.

Why not? A recent news flurry surrounds Pfizer’s announcement that it will now become a foreign company so it can avoid US corporate tax and grab money set aside abroad for US tax liabilities. But that’s only the tail on a long list of favors granted it and other drug companies.

I write a lot. Imagine if I put my work under copyright, then lobbied to have a law passed that creates millions of subsidized customers who can have my work for free because I’m billing the government. Of course, I should be allowed to set almost any price for what the government pays on behalf of those customers. And the government could promise to book and magazine sellers that their profits would rise automatically with sales of my writings. Meanwhile, I’ve been around long enough that I’ve got a good share of my income deferred from tax until I draw down my 401(k) accounts, so I should be allowed to rent a shack somewhere abroad, claim a foreign residence, and avoid ever paying tax on that income, even while I live in the States.

Now, don’t blame me if I respond naturally to all those incentives. Or lobby Congress to maintain them. And don’t blame me if I end up producing things less worthwhile than what I could produce. Hey, it’s a free country.

How about you? Maybe together we can invent a company for workers and could be granted power to charge anything we want for providing that work to a large set of government-subsidized customers. We shouldn’t have to pay tax, given all we are doing for the economy. We could get some deep-thinking consulting firms to prove that this would probably solve any future unemployment problem.

What do you say, Santa? For goodness sake, you know I’ve been good, and I’m not pouting. With this wish, I’m just asking for what your competitor, Congress, gave the drug company next door.

Recent Social Security reform doesn’t fix unfair spousal benefits

Posted: November 5, 2015 Filed under: Aging, Columns, Income and Wealth 1 Comment »The budget compromise forged by Congress and the Obama administration at the end of last month makes two fundamental changes in Social Security. First, it denies a worker the opportunity to take a spousal benefit and simultaneously delay his or her own worker benefit. Second, it stops the “file and suspend” technique, where a worker files for retirement benefits then suspends them in order to generate a spousal benefit.

Unfortunately, neither of these changes gets to the root issue: that spousal and survivor benefits are unfair, although the reform redefines who wins and who loses. Social Security spousal and survivor benefits are so peculiarly designed that they would be judged illegal and discriminatory if private pension or retirement plans tried to implement them. They violate the simple notion of equal justice under the law. And as far as the benefits are meant to adequately support spouses and dependents in retirement, they are badly and regressively targeted.

As designed, spousal and survivor benefits are “free” add-ons: a worker pays no additional taxes for them. Imagine you and I earn the same salary and have the same life expectancy, but I have a non-working spouse and you are unmarried. We pay the same Social Security taxes, but while I am alive and retired, my family’s annual benefits will be 50 percent higher than yours because of my non-working spouse’s benefits. If I die first, she’ll get years of my full worker benefit as survivor benefits.

Today, spousal and survivor benefits are often worth hundreds of thousands of dollars for the non-working spouse. If both spouses work, on the other hand, the add-on is reduced by any benefit the second worker earns in his or her own right.

An historical artifact, spousal and survivor benefits were based on the notion that the stereotypical woman staying home and taking care of children needed additional support. That stereotype was never very accurate. And today a much larger share of the population, including those with children, is single or divorced. Plus, many people have been married more than once, and most married couples have two earners who pay Social Security taxes.

Where does the money for spousal and survivor benefits come from? In the private sector, a worker pays for survivor or spousal benefits by taking an actuarially fair reduction in his or her own benefit. In the Social Security system, single individuals and married couples with roughly equal earnings pay the most:

- Single people and individuals who have not been married for 10 years to any one person pay for spousal and survivor benefits, but don’t get them. This group includes many single heads of households raising children.

- Couples with roughly equal earnings usually gain little or nothing from spousal and survivor benefits. Their worker benefit is higher than any spousal benefit, and their survivor benefit is roughly the same as their worker benefit.

The vast majority of couples with unequal earnings fall between the big winners and big losers.

Such a system causes innumerable inequities:

- A poor or middle-income single head of household raising children will pay tens of thousands of dollars more in taxes and often receive tens of thousands of dollars fewer in benefits than a high-income spouse who doesn’t work, doesn’t pay taxes and doesn’t raise children.

- A one-worker couple earning $80,000 annually gets tens of thousands of dollars more in expected benefits than a two-worker couple with each spouse earning $40,000, even though the two-worker couple pays the same amount of taxes and typically has higher work expenses.

- A person divorcing after nine years and 11 months of marriage gets no spousal or survivor benefits, while one divorcing at 10 years and one month gets the same full benefit as one divorcing after 40 years.

- In many European countries that created benefit systems around the same stereotypical stay-at-home woman, the spousal benefits are more equal among classes. In the United States, spouses who marry the richest workers get the most.

- One worker can generate multiple spousal and survivor benefits through several marriages, yet not pay a dime extra.

- Because of the lack of fair actuarial adjustment by age, a man with a much younger wife will receive much higher family benefits than one with a wife roughly the same age as him.

When Social Security reform eliminated the earnings test in 2000 and provided a delayed retirement credit after the normal retirement age, some couples figured out ways to get some extra spousal benefits (and sometimes child benefits) for a few years. After the normal retirement age (today, age 66), they weren’t “deemed” to apply for worker and spousal benefits at the same time, allowing them to build up retirement credits even while receiving spousal benefits. Other couples, through “file and suspend,” got spousal benefits for a few years while neither spouse received worker benefits.

These games were played by a select few, although the numbers were increasing. Social Security personnel almost never alerted people to these opportunities and often led them to make disadvantageous choices. Over the years, I’ve met many highly educated people who are totally surprised by this structure. Larry Kotlikoff, in particular, has formally provided advice through multiple venues.

So is tightening the screws on one leak among many fair? It penalizes both those who already have unfairly high benefits and those who get less than a fair share. It reduces the reward for game playing, but like all transitions, it penalizes those who laid out retirement plans based on this game being available. It cuts back only modestly and haphazardly on the long-term deficit. As for the single parents raising children — perhaps the most sympathetic group in this whole affair — they got no free spousal and survivor benefits before, and they get none after.

The right way to reform this part of Social Security would be to first design spousal and survivor benefits in an actuarially fair way. Then, we need better target any additional redistributions on those with lower incomes or higher needs in retirement, through minimum benefits and other adjustments that would apply to all workers, whether single or married, not just to spouses and survivors.

As long as we keep reforming Social Security ad hoc, we can expect these benefit inequities to continue. I fear that the much larger reform required to restore some long-term sustainability to the system will simply consolidate a bunch of ad hoc reforms and maintain these inequities for generations.

This column originally appeared on PBS Newshour’s Making Sen$e.