Education Presidents And Governors: Ain’t Gonna Happen

Posted: February 20, 2013 Filed under: Children, Columns, Taxes and Budget 24 Comments »In last week’s State of the Union speech, President Obama put great emphasis on expanding early childhood education. He’s not alone in recognizing the vital role of education as the launching pad for 21st century growth. George W. Bush wanted to be known as the “education president,” and so did his father, George H.W. Bush.

Many governors have similar aspirations. Jerry Brown, for instance, has gotten headlines for his efforts to restore the California university system to its former high status. State support for higher education has fallen dramatically there, particularly as a share of the budget and of Californians’ incomes but also in real terms. Brown even supported a tax increase to try to reverse this trend.

While I strongly support these types of effort, right now pro-education governors and the president are fighting a losing battle. Their new initiatives merely slow down their retreat against a health cost juggernaut.

California isn’t much different from many other states. The college bound and their parents witness this declining state support in the form of ever-rising costs and student debt. Less recognized is the fall in academic rankings of the nation’s leading public universities, such as many of the formerly extolled California universities and my own alma mater, the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

State support of education hasn’t just declined at postsecondary schools. In recent years, legislators have assigned K–12 education smaller shares of state budgets as well. During the recession, teachers were laid off and not replaced in many states. Efforts to expand early childhood education have also stalled, although the president’s initiative may give it some temporary momentum.

Federal spending policies only reinforce the longer-term anti-education trend. An annual Urban Institute study on the children’s budget suggests future continual declines in total federal support for education as long as current policies and laws hold up.

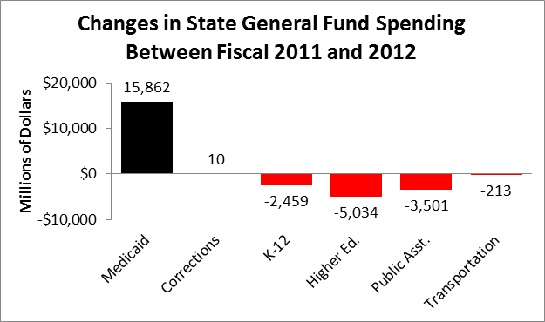

Education spending will continue to decline as long as health costs keep rising rapidly and eating up so much of the additional government revenues that accompany economic growth. The figure below, prepared by National Governors Association (NGA) Executive Director Dan Crippen and presented by his deputy, Barry Anderson, at a recent National Academy of Social Insurance conference, tells much of the state story: health costs essentially squeeze out almost everything else.

Fiscal 2011 data based on enacted budgets; fiscal 2012 data based on governor’s proposed budgets

Source: National Association of State Budget Officers, as presented by Dan Crippen, National Governors Association

These rising health costs don’t just place a squeeze on government budgets; they also are one source of the paltry growth in median household cash income over recent decades.

Within states, health costs show up primarily in the Medicaid budget. As the NGA numbers demonstrate, recent federal health reform did little and is expected to do little to control these state costs, despite large, mainly federally financed subsidies for expanding the number of people eligible for benefits.

With populations aging, state and federal governments now also face demographic pressures to increase their health budgets. Large shares of the Medicaid budget go for long-term and similar support for the elderly and the disabled. This budgetary threat also extends to revenues as larger shares of the population retire, earn less, and pay fewer taxes.

The next time someone tells you that we should wait another ten years to control health costs because we’ll be so much smarter and less partisan then, remind him or her that this procrastinating implicitly advocates further zeroing out state and federal spending on education—and the children’s budget more generally. Presidents and governors will never succeed with their education initiatives until they stop the health cost juggernaut in its tracks.

Desperately Needed: A Strong Treasury Department

Posted: February 13, 2013 Filed under: Columns, Taxes and Budget 2 Comments »Alexander Hamilton, the first Secretary of the Treasury, set the bar very high. The Senate is about to begin debate over President Obama’s nomination of Jack Lew to be Treasury Secretary. Lately, confirmation hearings have often focused on either the personal foibles of candidates or relatively evanescent policy disputes that are soon forgotten. But at a time when fiscal policy is so critical to the nation’s well-being, the Senate should not forget the critical role Treasury has played in forging that agenda.

The key question for the Senate: will Treasury continue to play that powerful role under Lew’s stewardship?

While Hamilton could be mercurial and even buffoonish in his monarchial tendencies and late military ambitions, he was extraordinarily visionary in molding institutions and organizations to meet the fiscal needs of the new nation. Whether writing Federalist Papers or engaging in the nation’s first Grand Bargain on the budget—to pay off Revolutionary War debt in exchange for the establishment of the capital in the District of Columbia—his prescient gaze stretched far into the future, finding limitless possibility for this great nation.

Perhaps nowhere is his legacy more embodied than in the Treasury Department that he helped create and nurture to handle the nation’s debt obligations, taxes, and its budget. That legacy has been threatened by a modern department weakened by the usurpation of its functions.

Remember that the president is the only elected official our founders explicitly tasked to represent the nation as a whole. We expect partisanship among members of Congress because they represent different constituencies, though today the influence of special interests transcends congressional boundaries. The Chamber of Commerce, AARP, National Rifle Association, and AFL-CIO each understand the levers of power, even to the point of knowing how to scare an entire legislature to inaction with a few million dollars of campaign contributions or “scare” leaflets to their membership. I’m not saying that these groups don’t have views worthy of consideration, but they do not—I repeat, do not—represent the “general welfare” that our Constitution explicitly mentions in its preamble and its taxing and spending clause.

The executive branch is no longer organized along a few simple lines such as treasury, state, defense (or war), and justice—departments dedicated to what might be considered general welfare functions. The branch is now dominated by departments dedicated to special constituencies or tasks that generate special interest pleading such as agriculture, commerce, labor, housing, health and human services, and education. In turn, the White House is full of individuals whose jobs revolve around placating these constituencies, as well as pollsters and political advisors whose jobs center more on sound bites than sound policy.

Interestingly, one of the earliest fights between our political parties was over whether the federal government should get involved in arenas like agriculture or education. While Hamilton, was on the side of those favoring those efforts, both sides agreed that if such spending took place, it should still favor the general interest and not favor any specific section of the country over another. Today, particular constituencies are the dominant beneficiaries of many of our spending and tax subsidy programs. Does anyone really think that subsidies for sugar growers or early retirees or owners of oil companies and expensive vacation homes serve the general welfare?

When it comes to spending, taxing, and budgeting in the modern era—especially when the government has made too many promises to too many people—the Treasury Department remains the only agency that can restore order by offering broad reform packages centered on the general welfare.

Other arms of government simply lack the tools to deal with today’s unique fiscal challenges. If we set aside those mainly focused on special constituencies or tasks, the options are limited. The White House can and should help the president agree to propose what should be built, but it doesn’t have the personnel to figure out its plumbing and engineering. The only two budget competitors might be the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) and the Office of Management and Budget (OMB). CBO serves the Congress and not the President, and it abstains from proposing policy, partly to protect its now-ascendant role as neutral scorekeeper. Neither CBO nor OMB puts together cross-cutting packages the way that Treasury has done, when allowed. They do provide laundry lists of options, but that tends to foreclose, say, adopting an efficiency improvement in one area and offsetting its potentially regressive effects in another. OMB, in turn, has few economists on staff and has little tradition in issuing reports.

Treasury also sits in the unique position of having to worry about the ways and means of paying for things. It alone must deal with what I call the “take-away” side of the budget ledger. Constantly confronting how to administer taxes or float bonds, it’s in its very blood to balance potential benefits with costs and reduce politicians’ incentive to operate on the “give-away” side of the budget by enacting tax cuts and spending increases for which future generations will have to pay.

One other part to solving our fiscal puzzle involves understanding the role of committees or assemblies of politicians. The role of these groups is to approve, not design, policy, and delegating that latter function to them neglects the role of the executive in both business and government. There was a reason fiscal policy shifted to a strong Treasury and away from the committees operating under the weak Articles of Confederation.

In assuming the executive role of Treasury Secretary, will Jack Lew follow Hamilton’s example by leaving a stronger Treasury as a legacy? Will he help move us down a viable path for getting out of our current fiscal mess? I suggest he is unlikely to succeed at one without accomplishing the other.

Who Is Insured or Not Insured by Government?

Posted: February 6, 2013 Filed under: Columns, Health and Health Policy, Taxes and Budget 3 Comments »One of the many dilemmas surrounding federal health care policies is that the government only partially insures most people when it subsidizes health care, but we want to pretend that once “insured” we are all entitled to the maximum health care available. This puts a lot of weight on the definition of “insurance” and creates misunderstandings about what the government does and does not do.

This issue came up in a column by Bruce Bartlett, who notes that Republicans may now oppose an individual mandate, but they do support (directly or indirectly) a mandate on hospitals to provide emergency care. Moreover, while ignoring their effective support of this mandate, and the effective taxes necessary to pay for it, Republicans maintain that the emergency-care mandate means that everyone has some amount of insurance coverage, however partial it may be.

This debate raises the question of what it means to be “insured.” No government plan covers everything. For those soon to have access to the exchange subsidy available through Obamacare, the “silver” and “bronze” plans that could be subsidized still cover only some costs. Medicaid, in turn, generally pays providers less than do other insurance plans; as one result, the more highly paid (and, often, more highly skilled) providers are less available. Similarly, Medicare does not cover all health services, including long-term care, and some doctors now refuse new Medicare patients, though that system’s payment rate is still higher than Medicaid’s.

You may argue that you want equal coverage—if some people get Cadillac coverage, everyone should. However, no elected official from either party seems willing to raise the taxes necessary to pay for such an expensive system. The reason is obvious: such health care would absorb all the revenue currently raised by the federal government and then some, leaving nothing for other government functions.

Even then, some people would step outside the system and buy a Mercedes policy, so inequality in health care would remain. Thus, the notion that everyone gets the same health insurance coverage, even in the most nationalized health system, is pure myth. But if people are not going to receive the Cadillac or Mercedes coverage from government that others obtain privately, how should Congress design policy with those multiple gaps in mind?

I don’t think there is any easy answer, but I do think that researchers and analysts should be more precise when reporting on “insurance” coverage. For example, the Congressional Budget Office produces counts of how many people would be insured under various options, but such estimates by themselves are misleading. Insured and not insured for what? For instance, if everyone received a simple (say, $5,000) voucher, with few restrictions other than that it must cover health care, almost everyone would buy at least a $5,000 insurance policy. On the other hand, if government dictated that the voucher had to be used to buy an expensive plan that many people couldn’t afford, then supplying a voucher would not produce fairly universal (yet partial) coverage.

Alternatively, one can’t assume that a highly regulated system will automatically provide whatever care is specified, since what it pays affects which providers participate in the system. The implicit assumption—and I am not judging it here—may be that many providers are so overpaid that cutbacks would have only limited effect on the care provided or the quality of the doctors and nurses who would accept a lower-paying career.

The ideal but difficult approach for researchers and budget offices, I think, is to note as best as possible what coverage is provided by regulation or subsidization of emergency rooms, Medicaid, Medicare, exchanges—indeed, of each government engagement in the health care economy. Note the expected gaps, whether in preventive care, higher-priced doctors, drugs, or other services. Finally, compare the extent to taxpayers and insured individuals avoid coverage gaps by paying higher taxes or more for their insurance.

In any case, a dichotomous count of who is “insured” or “not insured” is too simplistic. Almost any government health insurance policy is partial in care and cost. If Republicans want to claim that emergency room care is a type of insurance, then they should also acknowledge what is not insured through that mechanism and the implicit taxes on those who end up covering the emergency room cost. If Democrats want to claim that vouchers provide less insurance than a more regulated system, then they, too, should specify just what additional insurance they claim will be covered, at what cost to whom. Both parties should also make coverage comparisons for systems that are equally cost constrained.

Henry Ford, the American Experience, and Why and How the Distribution of Income Affects Growth in the Modern Economy

Posted: January 29, 2013 Filed under: Columns, Economic Growth and Productivity, Income and Wealth 3 Comments »One hundred years ago Henry Ford dropped the price of his Model T to $550. Having adopted new and successful engineering and assembly techniques, the company’s sales expanded exponentially, approximately tripling between 1911 and 1914 alone. Henry Ford bragged that his car would be “so low in price that no man making a good salary will be unable to own one.”

On the American Experience (January 29, 2013) PBS covers the biography of Henry Ford. That story has application to our own time in explaining how the distribution of income affects economic growth.

Ever since the Industrial Revolution, economies of scale—mass production with lower cost for the last items produced than for the first—have been the primary engine of income growth for nations and workers. Ford’s talent at mass production not only made him extraordinarily rich, it helped increase the effective incomes of workers throughout the country since their earnings could go farther. While massive rewards did accrue to entrepreneurs, inventors, and those gaining temporary monopolies, the rising tide lifted all boats; it even leveled out the gains as the forces of competition limited how much leading capitalists could garner for their efforts of yesteryear.

Henry Ford’s fight with unions to the side, he did recognize from the start that workers needed to earn enough to buy his products. I’m not suggesting that the cart of workers’ incomes leads the horse of profits, but rather that they move forward together. Ford at least knew that he and some of the other rich people he tended to detest could use only so many cars themselves; if the everyday citizen couldn’t buy them, he could never get rich.

So how did we move toward a society where today profits seem to be rising but workers’ incomes remain stagnant? The main answer, I believe, is that while economies of scale have expanded extraordinarily since Ford’s day, the necessary purchasers of the new products lie within a global economy. The growth of U.S. workers’ incomes is less necessary for the producers of new goods and services to become wealthy.

Consider how many modern-day Henry Fords produce goods and services with limited physical content: pharmaceutical drugs, electronic software, technology, movies, and other forms of entertainment and information. These “industries” provide much of the growth of the modern U.S. economy.

Many products within these growth industries can be produced at almost no cost for the next or marginal purchaser. How much does it cost Hollywood producers to let one more person watch a movie? For the drug manufacturers to produce one more pill? For Microsoft or Apple to make software available to one more person? Almost nothing in many cases, other than marketing. As economies of scale expanded as we moved through the 20th to the 21st century, so, too, have the possibilities for growth when more people have enough money to buy these new products. If the costs of a pill or movie can be shared among 10 million people, rather than 1 million, then the world economy can expand quickly when 9 million more people can afford to buy the product.

These economies extend beyond production to transportation, storage, and similar costs. It doesn’t cost much to “transport” a movie to Monaco, a pill to Paris, or software to Sofia.

Modern capitalists seek their buyers within a world population of 7 billion, not a U.S. population of 300 million. When creating products with extraordinary economies of scale that are easily transportable, at low weight or even with the click of a mouse button, the new American entrepreneur still wants purchasers whose incomes rise enough to buy these new goods and services. It’s just less necessary that those purchasers reside in the United States.

Does this mean that income becomes increasingly unequal? It depends partly upon whom you count and what type of measure you use. Almost no one could have guessed even a few decades ago the rise of hundreds of millions of middle-class people in China and India. At the same time, it’s also possible that incomes will rise initially for U.S. and Indian entrepreneurs and for workers in Bangalore, but not for large portions of the population in either the United States or India.

I am not arguing that all the consequences of this world order are sanguine. But only by defining its characteristics can we identify our opportunities.

First, consider how substantial economies of scale make higher growth rates possible when incomes rise across the board. Productivity just doesn’t rise as quickly when we build and subsidize McMansions for the few rather than employ workers to provide goods and services with greater economies of scale for the many.

Similar calculations can affect welfare policy. It may not cost us very much directly to give lower-income people the ability to buy goods and services with large economies of scale. For instance, if we give a household $1,000 that it uses to buy a television subscription that at the margin costs a cable company only an additional $100 to provide, then the net cost to the non-welfare part of society may also be only $100 despite the transfer of $1,000. At the same time, if the $1,000 subsidy at a $100 marginal cost of production results in plus $900 to a monopoly cable company and minus $1,000 to the taxpayer, then both the welfare recipient and the taxpayer may have reduced incentive to work. Private income (before welfare) also becomes more unequal.

Or consider antitrust policy. Tying it to its 19th century moorings may be inadequate for a 21st century economy. International competition may lessen any concern over having only four major American automobile manufacturers, but what about the concentration of accounting practices among the Big Four? Did the breakup of Arthur Andersen for its accounting indiscretions promote or reduce competition?

What about our current multi-tiered pricing of drugs, higher at home and lower abroad? Without any compensating mechanism, does this increase net output from the United States but at an unfair cost to U.S. consumers?

To answer all these questions, we need to concentrate correctly on causes, not inveigh interminably on impressions. One conclusion from Henry Ford’s day still stands out in my mind: promoting greater growth means both a favorable climate for entrepreneurship and a sharing of its rewards broadly with workers.

Our Imperfect Work

Posted: January 22, 2013 Filed under: Columns, Taxes and Budget 13 Comments »“We must act, knowing that our work will be imperfect,” Barack Obama proclaimed in his second inaugural address. Interestingly, the Washington Post blazoned its front page with the first three words without noting the succeeding dependent clause. Yet within this clause, I believe, lies the means by which the president—and Congress—and we—can move past so many of our conflicts and face up to the problems that confront us. The solution lies not in acting, but in recognizing the imperfection of what we do. If our budgets are to be vehicles for change, then we cannot enact so many laws as if the priorities of one time and place must endure forever.

More than ever before, our recent fights carry with them the implication that victory must be complete and total, setting in stone the institutions that will rule over our successors for decades and centuries to come. “We must act,” each political party seems to say, “as if our work will be perfect, else our opponents may someday slow down or even reverse our course.” Permanent monuments must be made to some liberal or conservative agenda, regardless of whether that monument rests upon unstable ground, employs an architecture glued together from incongruous designs, or fails to leave room for the improvements that only future knowledge may reveal.

Today, if we favor Social Security, it must be maintained permanently in its ancient design. For all generations of ever-expanding life expectancies, we must allow beneficiaries to retire as early as 65, or, when feeling temporarily richer, at 62. We must even accept its 1940s stereotype of the two-parent family, with abandoned mothers required to pay taxes to support spousal benefits for which they are ineligible. Similarly, if we favor less government, we can’t just work toward that goal by reducing spending. No, we have to create permanent tax cuts even if that means running economically disastrous deficits.

If we favor helping the poor, then we can never give up support for benefits like SNAP or food stamps. These programs must be etched in the law as superior to any alternative use of those funds, including ones that might provide better opportunities to people in need. If we subsidize an industry, whether oil or alternative fuel or agriculture or manufacturing, then we must enshrine that subsidy in the tax code.

Now, of course, there’s good reason for using legislation to try to provide some certainty or security. With perfect foreknowledge, we can plan for the future. But what if that future remains uncertain? Planning for it then requires creating a way to respond to its surprises, good and bad.

Unfortunately, we’ve gone long past the point where our federal budget could be flexible. A fiscal democracy index I developed with Tim Roeper shows that the combination of entitlement growth and low revenues means that today most revenues are already committed to permanent spending programs. Almost every congressional decision to adjust national priorities has to be paid for out of a deficit, or by overturning some past “permanent” enactment.

Earlier, before entitlements became so prevalent and dominant, spending was largely discretionary. Congress also felt that we should pay our bills on time, so it didn’t finance tax cuts for today’s generations by passing those liabilities onto future generations. Though many programs survived for decades, most still had to receive new votes of support. Even more important, almost none had any built-in growth. That made it easy to let some ideas languish as others came into prominence, leaving room for new choices or reconsideration over time.

Compromise is much easier when one side or the other isn’t forced into reneging on past promises to the public. It’s easier when it’s possible down the road to proceed on the same course, pursue the same objective via a different course, or decide on both a new objective and course. It’s easier when we’re not asking our opponents to keep funding some permanent monument we want erected to ourselves.

“But we have always understood that when times change, so must we; that fidelity to our founding principles requires new responses to new challenges…We understand that outworn programs are inadequate to the needs of our time…Let us answer the call of history, and carry into an uncertain future that precious light of freedom.” (Barack Obama, January 21, 2013; emphasis mine).

The Decline of Fiscal Democracy in America: A New Video Series by Eugene Steuerle

Posted: January 7, 2013 Filed under: Columns, Taxes and Budget 3 Comments »On January 3, 2013, the 113th session of the U.S. Congress opened with a fiscal cliff averted, but a country still stuck in a less-recognized fiscal bind.

In the first video of a three-part series, I explore one of the major reasons recent Congresses have been so dysfunctional: all, or almost all, the revenue to be collected by the Treasury Department was spent before lawmakers walked in the door.

I further discuss how spending and tax subsidy programs on autopilot, along with a tax system inadequate to pay our bills and rife with gaping holes, handicap lawmakers’ and the public’s ability to set new goals for solving today’s and tomorrow’s problems.

The Case for Optimism in the New Year: Still Standing on the Shoulders of our Forebears

Posted: January 3, 2013 Filed under: Columns, Economic Growth and Productivity, Taxes and Budget 2 Comments »With all the silliness going on in Washington these days, and with recovery from recession slow here and halting in many other developed nations, we could easily adopt a pessimistic attitude that obscures the prospects lying right at our feet. At the beginning of a new year, I think we instead need to pause and reflect on our graces and blessings, even as we confront the obstacles we have placed in the way of realizing our potential.

First, let’s not translate politicians’ largely self-imposed requirement to make some tough economic choices into the false premise that we lack resources to do anything new, much less better. Are we poor? Hardly. We’re richer than almost any country anywhere and anytime. If we’re growing more slowly than we expect, that only means we’re getting richer more moderately. With average gross domestic product per household now exceeding $125,000, we can easily get misled by focusing on gloomy statistics that exclude or don’t count for improvements.

Here are some among the many pieces of evidence that we often ignore: the ever-better health care that we receive annually through almost any insurance plan, whether employer- or government-provided; the steady increase in life expectancy; and the improvement in the quality of our computers, telecommunications, automobiles, and other durable goods.

Is the public sector in decline? Well, it might be dysfunctional, and it might not be growing as fast as it did in recent decades, but consider: federal and state government spending, including tax subsidies, exceeds $50,000 per household. That amount is greater than the average real income of households from all sources, public and private, in the early 1960s. Transfer programs are more than 50 percent larger than when Ronald Reagan became president. Look closely at every proposed budget, Democratic or Republican, and you will see that they project incomes will increase by about 30 percent—or $5 trillion in today’s dollars—in about a decade. Meanwhile, government spending and revenues will grow by a similar share, perhaps a bit less under one political party than the other. (I hesitate to say that it will grow more slowly under Republicans, since history often belies that conventional wisdom.)

Compare what is required to get the budget in order with what economic growth normally makes possible. Want to reduce budget deficits by, say, 5 percentage points of GDP or about $1 trillion annually in another decade? That’s just a fraction of the rise in incomes that we expect and hope to achieve, yet it’s far more than either political party has come close to suggesting, and probably more than necessary. To top it off, deficit reduction does not mean reduced wealth any more than paying off a credit card does. It merely means that we accept paying more of our bills now rather than passing the liabilities onto our children.

Why the optimism surrounding economic growth? We stand on the shoulders of those who have gone before us. They passed onto us all their knowledge and left us with a country rich in citizens and communities, institutions and inventions, rights and resources. We have a long-established history of entrepreneurial ingenuity; a flexible labor force; the world’s most thriving set of charities, associations, and universities; and, for all our petty bickering, a people united by belief in our republic, and not, as in so many countries, divided by clan or tribe or religion. Even our barriers of race and gender have been falling away, much to the benefit of everyone, not just those who suffer from discrimination.

Not that countries can’t go into decline. Argentina early in the 20th century, Bosnia more recently, and Yemen today provide warnings. The overpromised political systems of Japan, Western Europe, and the United States provide new threats, as does population and labor force decline in some countries. The young are falling behind previous generations in their accumulation of wealth, many people of color have stopped catching up as they did in the past, and our educational systems are showing few gains. Too unequal a distribution of income and wealth also threatens growth for both social and economic reasons (on which I will elaborate little here other than to note how much modern growth everywhere has been correlated with a thriving middle class).

Yes, all these problems threaten us at a time when our political institutions appear to have languished and gone into decline. Yet, even that problem, I believe, reflects a search for a fundamental government transformation that has occurred only a few times in our vibrant, yet still young and ever-challenging, democratic experiment.

At the beginning of another year, therefore, let’s resolve to recognize within our challenges the extraordinary opportunities we, too, possess for bequeathing a better world to our children.

Why Do We Keep Jumping Over the Fiscal Cliff with Bungee Cords?

Posted: December 21, 2012 Filed under: Columns, Taxes and Budget 4 Comments »Updated January 11, 2013

As I and many others predicted, we didn’t plunge down the fiscal cliff at the end of 2012. But we’ll be back at the edge again soon, for refusing to borrow the money required to pay bills Congress has already rung up, or for threatening some extraordinarily badly designed sequestration or across-the-board cut in discretionary spending. And while I didn’t think last month that politicians would let tax rates skyrocket at the beginning of 2013, and I don’t think now that they will refuse to pay foreign lenders, Social Security recipients, or doctors, I don’t like jumping over cliffs with bungee cords attached. It’s a notoriously bad use of time and energy. Plus, I don’t trust the bungee cords.

Either way, people keep asking, why can’t these guys and gals just get together and compromise?

The main answer, I believe, goes beyond silly pledges not to raise taxes or touch anyone’s Social Security benefits. It’s the failure of both political parties to come clean on either the math or its implications, and the accompanying failure to reframe the public debate after our contentious last election.

Consider the plethora of misleading political rhetoric that both parties use in playing the blame game and asserting how they are trying to protect the middle class from bearing any burden for anything, any time, and anywhere. Almost every statement by President Obama or Speaker Boehner emphasizes how much he wants to protect 98 or 99 or 99.5 percent of us from having to pay more in taxes. That a middle-class family might have to pay a couple of thousand dollars more (the Tax Policy Center estimate of the tax increase for the median-income family if we had gone over the cliff at the end of 2012) is put forward as horrendous and unfair to those who “play by the rules.”

Wait a second! We are running deficits of about $9,000 per household a year right now. Those bills don’t disappear simply because we refuse to pay even $2,000 of them currently. We merely shove those costs to the future, mainly onto the young, some of whom are too young to vote. Convincing people that they can’t possibly afford to get by with $2,000 less when they’re running up credit card bills of $9,000 a year is simply dishonest. If we aim to borrow $2,000 less from foreigners by 2015 or 2016, for instance, it may mean that by then we also must consume $2,000 less relative to what we produce as a society, even if we “play by the rules.”

Let me be clear. Most economic analysis says that a country can’t dampen consumption too quickly without threatening economic growth. Still, the basic bind that both parties placed on themselves comes from promising so much to the middle class in terms of both high benefits and low taxes. The public fight over the fiscal cliff centered mainly on taxing the rich. But spending, mainly in unsustainable growth in health and retirement programs, remains the dominant long-term issue. Confining tax increases to a very small share of the population doesn’t exempt the middle class from dealing with those issues; to the contrary, it only increases the burden they must bear in spending cuts in lieu of the tax increases they avoided.

Neither party, however, can easily go to the middle class and say, “Look at how I protected you from paying more taxes so you can now get fewer benefits.” Each side criticizes the other for not offering much on reform of large health and retirement programs, but they know the consequences for leading. If the Republican Party presents its proposal first, it knows that Democrats will immediately claim that Republicans favor cuts in, say, Medicare over yet-further tax increases on the wealthy. If the Democratic Party presents any adjustments to eligibility or benefit levels, it risks losing a large share of its constituency and abandoning the one issue on which it has won elections for so many years. It’s not that the Democrats won’t compromise, they just want to be able to blame Republicans for whatever happens to the middle class. Similarly, it’s not that Republicans don’t want entitlement reform, they just don’t want to bear the brunt of the criticism by themselves.

To make matters even more complicated, almost all the bargaining centers only on ameliorating, not resolving, our long-term problem. This means the fight will continue for years, so each party wants to position itself for the next and then the next round of debates.

The broader issue needs to be reframed, somewhat like Erskine Bowles and Alan Simpson did, with a fuller, shared-party explanation to the public that we’re all in this together. It was too late for that at the end of 2012, and will be too late again the next time we focus our attention primarily on avoiding some precipice. But without that broader type of effort, this fight is not going away for a very long time.