Reforming Social Security Benefits

Posted: May 23, 2013 Filed under: Aging, Columns, Income and Wealth 18 Comments »Excerpt from “Reforming Social Security Benefits,” Testimony Before the House Ways and Means Subcommittee on Social Security.

In this testimony, I would like to focus on the need for Social Security benefit reform regardless of the current imbalances in the system or the taxes raised to support the system.

Why? Despite Social Security’s great success, its growth in lifetime benefits over time has been decreasingly targeted at its major goals. Even while programs for children and working families are being cut, combined lifetime benefits for couples turning 65 rise by an average of about $20,000 every year, so that couples in their mid-40s today are scheduled to get about $1.4 million in lifetime benefits, of which $700,000 is in Social Security.

Social Security has morphed into a middle-age retirement system. Typical couples are receiving close to three decades of benefits. Smaller and smaller shares of Social Security benefits are being devoted to people in their last years of life.

If people were to retire for the same number of years as they did when benefits were first paid in 1940, a person would on average retire at age 76 today rather than 64. Soon close to a third of adults will be on Social Security, retiring on average for a third of their adult lives.

While Social Security did a good job reducing poverty in its early years, it has made only modest progress recently, despite spending hundreds of billions of dollars more. The program discourages work among older Americans at the very time they have become a highly underused source of human capital in the economy.

The failure to provide equal justice permeates the system. It discriminates against single heads of household, spouses with relatively equal earnings, those who bear their children before age 40, long-term workers, and many others. At the same time, private retirement policy leaves most elderly households quite vulnerable.

Unfortunately, the Social Security debate has largely proceeded on the basis of being “for the box” or “against the box.” The contents themselves deserve scrutiny.

How might one break through the stalemate and find areas of mutual agreement? While I applaud the efforts of the Simpson/Bowles Commission and the Bipartisan Policy Commission I believe we can go much further to address the problems I just raised. How? We should start with a basic set of principles and see where they lead us.

Consider. Inevitably balance will be paid for mainly through benefit cuts or tax increases on higher income individuals who have most of the resources. That debate need not derail other needed reforms. I suggest proceeding in the following order:

First, consider reforms aimed at meeting Social Security’s primary purposes:

- providing greater protections for those truly old or with limited resources;

- supporting the work and saving base that undergird the system; and

- providing more equal justice for those suffering needless discrimination in the system, like single heads of household and longer-term workers.

Some of those fixes cost money, and some raise money; we don’t have to address trust fund and distributional consequences in each and every change.

Second, further adjust minimum benefits and the rate schedule and indexing of that schedule over time to achieve final cost and distributional goals. The extent of these adjustments will also depend upon the tax rate and base structure agreed upon.

My testimony provides a fairly detailed way to engage this type of reform process. It largely follows the logic I applied to taxation when serving as the economic coordinator of the Treasury effort that led to the bipartisan-supported Tax Reform Act of 1986, and in my testimony before the Simpson/Bowles Commission.

IRS and the Targeting of the Tea Party and Other Groups

Posted: May 14, 2013 Filed under: Columns, Nonprofits and Philanthropy, Taxes and Budget 1 Comment »To help clarify whether IRS incorrectly, unfairly, or illegally targeted the Tea Party and other conservative groups, here are the answers to a few basic questions.

1. Is it improper for IRS to target specific groups?

Almost every contact the IRS makes with select taxpayers derives from targeting. Because its resources are constrained, the IRS conducts only limited audits, examinations, or requests for information. For instance, if you give more than the average amount to charity, you’re more likely to be audited since there is more money at stake. If you run a small business, you have a greater ability to cheat than someone whose income is reported to IRS on a W-2 form. The only way the IRS can enforce compliance at a reasonable administrative cost is by targeting.

This is especially true for the tax-exempt arena. Because audits yield little or no revenue, the IRS tax-exempt division examines very few organizations. Therefore, the IRS must use some criteria to “target” which tax-exempt organizations to approach.

2. Does the IRS discriminate?

Picking out which organizations or taxpayers to examine meets the definition of statistical discrimination. Firms do this when they consider only college graduates for jobs; political parties do this when they offer selective access to their supporters. Discrimination is wrong when it implies unequal treatment under the law, such as when unequal punishment is meted out for the same crime, or when people of color have less access to the mortgage market.

3. Why then did IRS say it erred in targeting Tea Party and other organizations?

We don’t have all the data yet but organizations with a strong political orientation have a higher probability of pushing the borderline for what the law allows. The groups at the center of this controversy generally applied for exemption under IRS section 501 (c)(4) which requires, among other things, that its primary purpose cannot be election-related and cannot overtly support political candidates.

However, the IRS could have identified election-related activity as a practice worthy of extra attention without specifying “tea party” or similar labels to identify such organizations. Had it done so, it might not be facing a problem now.

IRS apparently initially thought it was just using these labels as a shortcut for such an identification. Had it been engaged early on, the national office might have been quicker to warn against this practice since it would tend to identify more Republican organizations than Democratic groups with similar motives. Who decided what when is still under investigation.

Remember IRS was under pressure to examine those c(4) organizations after applications grew rapidly in the wake of the Supreme Court’s 2010 Citizens United decision. If IRS waits until after an election, it’s generally too late to make any difference.

4. Why did IRS start with the exemption process rather than wait and see how the organizations behaved?

Because IRS audits so few tax-exempt organizations, noncompliance is a major problem. But often noncompliance is inadvertent. Organizations trying to do “good” fail to understand legal technicalities or why IRS should be worried about them at all. If the IRS can get these organizations to comply with the rules from the start, it has a better chance of minimizing future problems.

5. Well, then, why the heck is IRS even in this game in the first place?

A question asked by many. Unlike some other nations with charities’ bureaus or other government regulatory agencies, tax-exempt organizations in the U.S. are monitored mainly by IRS at the national level and the state attorneys general at the state level. The IRS efforts generally derive from the Congressional requirement that charitable dollars (for which there are deductions and exemptions) go mainly for charitable purposes and not others such as electioneering.

6. But c (4) or social welfare organizations don’t benefit from the charitable deduction, so why don’t those with political orientation just operate without tax exemption or c(4) status?

They could, but the tax exemption provides several benefits. The least important may be non-taxation of income from assets since many of these organizations don’t have that much in the way of assets to begin with. However, many contributors interpret (often incorrectly) tax exemption to mean that the organization has satisfied legal hurdles, thus making it easier to raise money. Some c(4) organizations are closely connected to charities or c(3) organizations that can accept charitable contributions, and sometimes there’s a synergy between the two. My colleague Howard Gleckman reminds us that c(4)s quickly became favored over an alternative “527” tax-exempt political designation because the former does not need to reveal its donors. Finally, tax exemption provides an easy way to insure that any temporary build-up of donations in excess of payouts is not interpreted as taxable income to the organization or its contributors.

7. What will be the end result of this flap?

Success at agencies like IRS is often measured by their ability to stay out of the news rather than on how well they do their job. I’m guessing this episode will only will increase the bunker-like incentives within the organization. It would be good if Congress used this as an opportunity to figure out how better to monitor tax-exempt organizations, or whether IRS has the capability under existing laws, but that isn’t likely to happen.

When Policy Meets Statistics: The Reinhart and Rogoff Study on Excessive Debt

Posted: May 3, 2013 Filed under: Columns, Economic Growth and Productivity, Taxes and Budget 1 Comment »Knowing how many of us economists toil away in obscurity on most research, I’m always intrigued by what catches the press’s and public’s attention. Take, for example, the significant attention paid to a 2010 study by Harvard economists Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff that concluded that countries with debt levels above 90 percent of GDP began showing slower rates of growth. When Thomas Herndon, Michael Ash and Robert Pollin, scholars at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, recently had trouble replicating Reinhart and Rogoff’s results, the debate played out in national news outlet.

Unfortunately, this discussion quickly devolved from substance to politics to arguments ad hominem. Without getting into the extent to which I or others can validate Reinhart and Rogoff’s (R&R’s) original findings, I offer six cautions for anyone witnessing this or a similar statistical debate with significant policy implications: (1) statistics should never be interpreted as showing more than simple but potentially useful correlations; (2) healthy skepticism is required for all social science research, which seldom gets replicated for validity; (3) all empirical economic work is based on history that will not repeat in the exact same form; (4) research can certainly contradict conventional wisdom but not reason; (5) arguments ad hominem, particularly by those with their own agendas, are unhelpful; and (6) be careful with labels and straw men.

- Correlation versus causation. It’s long been stressed that statistical tests never prove causation, not simply because they can’t but because researchers make many choices and assumptions, often of statistical convenience. This doesn’t mean statistics are useless. Just accept that any result merely shows that A and B seem to occur together even after trying to account for other influences under a huge range of never-fully-tested assumptions.

- Skepticism. A growing body of “research on research” shows that few social science experiments, and even many medical studies, are replicated. Also, positive results get published; negative results usually do not. R&R’s study was replicated mainly because it got an unusual amount of attention.

- History. The past never repeats itself exactly—or, as Heraclitus warns, “You could not step twice into the same river.” That historical interpretations are contained and sometimes couched in data analyses doesn’t mitigate this well-known caution.

- Reason versus conventional wisdom. The R&R debate mainly revolves around two reasonable notions. One is the simple arithmetic conclusion that debt can’t rise forever relative to national income, along with the related economic conclusion that higher levels of debt can and have been shown in many places to have consequences for investment, interest rates, ability to borrow, and how government revenues are spent. The other is that institutions, times, places, and circumstances matter greatly, and they affect how one should interpret past data, such as those presented by both R&R and their critics.

- Ad hominem arguments. R&R published some of their work with the Peterson Institute for International Economics, so some of those who attacked R&R may have considered the authors guilty by association because of Peter George Peterson’s concern about deficits and his contributions to that Institute. Peterson’s own “guilt” on budget issues seems to be that he became rich on Wall Street, although he favors higher taxes on what he calls “fat cats” like himself. Still, while many of those who engage in these attacks themselves fail to represent their own or their institution’s sources of funding, let’s be honest. Much social science research is funded in ways that doesn’t necessarily bias how the research is done, but rather what is researched in the first place. So, unless one fully engages and thoroughly analyzes every study, even the careful academic reader must often try to determine trustworthiness in other ways, such as whether the researchers report results only consistent with some special interest or political party.

- Labels and “straw men.” While we all use labels and straw men at times to set up the stories we tell, they at best simplify greatly. In this case, R&R are identified as advocates of “austerity” and their opponents as “Keynesians” advocating stimulus, both of which are nothing more than labels. Most budget analysts I know worry about deficits but vary widely in whether they would engage in more short-term stimulus or in how strongly they believe that a path toward long-term balance even requires austerity. For instance, is reducing some rate of growth of spending, no matter what its level, austerity? Is the Congressional Budget Office an advocate of austerity or Keynesian when it asserts that sequestration hurts the economy in the short run, but has long-run benefits relative to doing nothing about deficits?

The bottom line: use extreme caution no matter which economist you read or believe.

Full disclosure: I have spent most of my career at the Urban Institute or the Treasury Department, brief periods each at the Brookings Institution, American Enterprise Institute, and the Peter G. Peterson Foundation (which differs from the Peterson Institute for International Economics). I also serve or have served on many advisory groups and boards for such organizations as the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget and the Comptroller General of the United States. As a consequence, je m’accuse of being among the many economists limited more than I would like by what research is supported by those institutions or their funders.

On Dementia, Cost-of-Living Adjustments, and the Right Way to Reform Programs for the Elderly

Posted: April 16, 2013 Filed under: Aging, Columns, Economic Growth and Productivity, Health and Health Policy, Income and Wealth, Taxes and Budget 4 Comments »While the increase in dementia among the elderly and the president’s proposal to change the index used to provide cost-of-living adjustments (or COLAs) to Social Security recipients have both received prominent headlines recently, the discussions have largely been independent of one another. Yet any principled attempt to reform our elderly programs, including Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid long-term care, should consider them together.

A well-designed reform of elderly programs could and should accommodate some of the cost problems associated with dementia by back-loading a larger share of benefits in Social Security to older ages when these and other needs of old age increase. COLA adjustments, whatever their other merits, front-load the system by cutting back on benefits for the oldest the most and those in late middle age or their 60s hardly at all. That the president and Congress have limited ability to engage in these types of discussions and tackle multiple goals at the same time is yet one more example of how our political processes increasingly block us from fixing what ails us.

In a well-cited RAND study, Michael Hurd and his coauthors estimate that dementia-related care purchased in the marketplace will cost somewhere close to $0.25 trillion in 2040 (in 2010 dollars). That sounds like and is a lot of money, but Social Security and Medicare are expected to rise to cost over $3.5 trillion in that same year. Although I am greatly simplifying by ignoring such factors as how much of the $0.25 trillion would be covered by individuals and not the government or the effect of entitlement reform on costs, the raw comparison speaks for itself.

Simply put, some of the private and public budget problems associated with dementia, Alzheimer’s, and other growing problems for the older among the elderly could be addressed by providing higher cash benefits in older ages. Whatever the aggregate size of Social Security in general, one could pay for this reform by cutting back on benefits in younger ages of Social Security “old age insurance” receipt. This would not solve all the associated problems of dementia, but it would be a simple, effective, easy-to-administer step in the right direction. And, by concentrating benefits more in older ages, it would encourage working longer at a time when employment rates for the population as a whole are scheduled to decline.

But this is not the discussion we’re having. Instead, the president and many budget reformers put forward a proposal to adapt what many believe is a better measure of cost-of-living or price changes and apply it to almost all government programs, including Social Security. As a technical matter, a COLA adjustment doesn’t affect the growth in initial Social Security benefits for those who retire, only the inflation adjustment they get after they retire. At that point, they get a small annual cut—e.g. 3/10 of 1% the first year, 6/10 of 1% the second year, and so forth—that compounds every year in retirement, so that by the time beneficiaries are in their late 80s or 90s, some 25 or 30 years of lower COLAs add up to a cut in benefits of as much as 10 percent.

Social Security has never adjusted upward the earliest retirement age for increases in life expectancy. Instead, it reduced the earliest age from 65 to 62 in 1959 and 1962. As a consequence, the share of benefits going to those with 15 or more remaining years of expected receipt has risen dramatically over time, and the share to those with, say, less than 10 years of remaining life expectancy has declined. The COLA proposal, even with some very old age adjustments suggested by the president, would add to this long-term trend of making the program ever less available in relative terms for those in truly old age.

This is not to say that the COLA proposal should not be adopted. Who can oppose trying to measure something better? But attempts to fix systems like Social Security and other elderly programs one parameter or adjustment at a time cannot easily meet multiple worthwhile objectives. Similarly, efforts to back-load the system to meet the needs of true old age, as suggested here, should be coordinated with further adjustments—say, in minimum benefits—to avoid discriminating against those with shorter life expectancies.

With or without a better COLA, therefore, reform of Social Security and other elderly programs requires a more comprehensive approach if we are to meet the needs of old age as they evolve over time. Shouldn’t dementia be a higher priority than early retirement? If we’re going to spend $3 trillion or more annually on Social Security and Medicare by 2040, do we really think that the allocation of those funds be determined by formulas set in years like 1935 or 1965 or 1977, when much of the current system was cobbled together?

On Popes and Presidents, Curiae and Cabinets

Posted: March 26, 2013 Filed under: Columns 1 Comment »Our proclivities toward worshipping our leaders might not be genetic, but they can certainly be traced through the ages. We like our kings…for a while. We believe that if we could concentrate power in the hands of someone who understands us, the world, and maybe even the heavens above, someone who can crush the opposing tribe or -ism or evil, someone who can make things “right,” then we, too, will be all right.

I wonder how much this type of thinking sets up our popes and our presidents—our kings of today—for failure. It’s not simply that they are human and fallible, and, therefore, must disappoint our regal expectations. It’s that as chief administrators of vast bureaucracies, they fear delegating to others who, in failing, might threaten the trappings of the office. Popes and presidents must deceive us, and themselves, that they understand what’s necessary to run this bureaucracy, when in reality they comprehend a tiny fraction. So these leaders consolidate power in a few hands who manage their leaders’ aura.

It’s a losing game. In the end, our popes and presidents can only be strengthened in performing their duties once they understand how centralizing power in their curiae and White Houses weakens them.

Consider the similar paths of the Vatican and the White House over different timespans. As the world became far more complicated, and the talents and education of people more widespread and diffuse, these organs have increasingly centralized power into fewer, not more, decisionmakers. Within the Vatican, bishops, along with the people who in early church history used to help select them, must obey curial powerbrokers. Within the White House, Cabinet secretaries, sometimes unrecognized by their own president, must check their every action with White House political advisors and pundits.

If you’re a bishop today, among your chief tasks is to hide your sins and those of the priests you have ordained. The Vatican, which has never liked hearing bad news, has reinforced this tendency with the belief that ordination up the clerical hierarchy changes a person’s very nature; each higher level intercedes with God in ways not possible to those lower down the ontological chain. With that mindset, the public might be scandalized to discover that a cleric is so human that, like the rest of us, there’s nothing he does that someone else couldn’t do better.

We note with horror the depth and breadth of the child abuse cover-up, yet rest assured this is but one of the crimes and scandals that this church among others has concealed. I know personally a case where a priest with mental problems was stealing from his own parish. Marked bills were placed in the collection basket, but when the bishop was presented with this incontrovertible proof, he responded that the parish priest held all power and should be obeyed. Apparently, that priest had been sent from parish to parish each time his problems became more visible. Now, multiply that type of anecdote by the thousands.

If you’re the head of the IRS or the Social Security Administration, the White House judges your success mainly by the bad publicity you avoid, not by the number of taxpayers or beneficiaries you serve well. Heaven forbid that you confess you’re unable to administer policies so they could be reformed. Of course, presidential appointees will always avoid publicly criticizing policies their president is promoting; for better or worse, bureaucracies can’t tolerate inconsistent messaging. Today, however, those limits extend much further. Now the government enforces silence on publishing studies that reveal limitations on policies the White House simply doesn’t care about or want to tackle. Why stir up political opposition?

As the king’s protectors expand and centralize their power, they further weaken the organs of the institutions they supposedly support. White House officials brag that they, not the Treasury officials with more expertise, write tax policy. Vatican officials try to silence philosophers and theologians at Catholic institutions who for some reason believe that knowledge expands and evolves when the Vatican prefers to cast it as written on tablets only to be repeated.

There is a moral here. As education and knowledge are dispersed in advanced societies, so also must decision making. More mistakes will be made, it’s true, when more decisions are made by more people, but institutions will advance more. Both credit and blame will be more dispersed, reducing our dependence upon and criticism of a pope or president, whose human, not divine, task becomes redefined to guide a bureaucracy that helps multiply the best of what we, not he, has to offer.

Lost Generations? Wealth Building Among the Young

Posted: March 15, 2013 Filed under: Children, Columns, Economic Growth and Productivity, Income and Wealth, Race, Ethnicity, and Gender 19 Comments »The young have been faring poorly in the job market for some time now, a condition only exacerbated by the Great Recession. Now comes disturbing news that they are also falling behind in their share of society’s wealth and their rate of wealth accumulation.

Signe Mary McKernan, Caroline Ratcliffe, Sisi Zhang, and I recently examined how different age groups have shared in the rising net wealth of the U.S. economy. Despite the recent recession, our economy in 2010 was about twice as rich both in terms of average incomes and net worth as it was 27 years earlier in 1983. But not everyone shared equally in that growth.

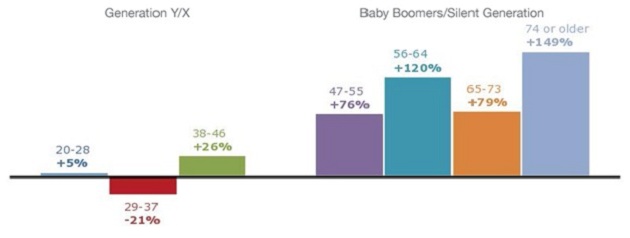

Younger generations have been particularly left behind. Roughly speaking, those under age 46 today, generally the Gen X and Gen Y cohorts, hadn’t accumulated any more wealth by the time they reached their 30s and 40s than their parents did over a quarter-century ago. By way of contrast, baby boomers and other older generations, or those over age 46, shared in the rising economy—they approximately doubled their net worth.

Older Generations Accumulate, Younger Generations Stagnate

Change in Average Net Worth by Age Group, 1983–2010

Source: Authors’ tabulations of the 1983, 1989, 1992, 1995, 1998, 2001, 2004, 2007, and 2010 Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF).

Notes: All dollar values are presented in 2010 dollars and data are weighted using SCF weights. The comparison is between people of the same age in 1983 and 2010.

Households usually add to their saving as they age, while income and wealth rise over time with economic growth. If these two patterns apply consistently and proportionately, then one might expect to see, say, a parent generation accumulate $100,000 by the time its members were in their 30s and $300,000 in their 60s, whereas their children might accumulate $200,000 by their 30s and $600,000 by their 60s.

This normal pattern no longer holds for the younger among us. However, this reversal didn’t just start with the Great Recession; it seems to have begun even before the turn of the century. The young increasingly have been left behind.

Potential causes are many. The Great Recession hit housing hard, but it particularly affected the young, who were more likely to have the largest balances on their loans and the least equity relative to their home values. If a house value fell 20 percent, a younger owner with 20 percent equity would lose 100 percent in housing net worth, whereas an older owner with the mortgage paid off would witness a drop of only 20 percent.

As for the stock market, it has provided very low returns over recent years, but those who hung on through the Great Recession had most of their net worth restored to pre-recession values. Bondholders usually came out ahead by the time the recession ended as interest rates fell and underlying bonds often increased in value. Also making out well were those with annuities from defined benefit pension plans and Social Security, whose values increase when interest rates fall (though the data noted above exclude those gains in asset values). Older generations hold a much higher percentage of their portfolios in assets that have recovered or appreciated since the Great Recession.

As I mentioned earlier, however, the tendency for lesser wealth accumulation among the younger generations has been occurring for some time, so the special hit they took in the Great Recession leaves out much of the story. Here we must search for other answers to the question of why the young have been falling behind. Likely candidates for their relatively worse status, many of which are correlated, include

- a lower rate of employment when in the workforce;

- delayed entry into the workforce and into periods of accumulating saving;

reduced relative pay, partly due to their first-time-ever lack of any higher educational achievement relative to past generations; - their delayed family formation, usually a harbinger and motivator of thrift and homebuilding;

- lower relative minimum wages; and

- higher shares of compensation taken out to pay for Social Security and health care, with less left over to save.

When it comes to conventional wisdom and media attention to distributional issues, there’s a tendency simply to attribute any particular disparity, such as the young falling behind in wealth holdings, to the growth in wealth inequality in society. But the two need not be correlated. Disparities can grow within both younger and older generations, without the young necessarily falling behind as a group.

Whatever the causes, we should also remember that public policy now places increased burdens on the young, whether in ever-higher interest payments on federal debts they will be left or the political exemption of older generations from paying for their underfunded retirement and health benefits. At the same time, state and local governments have given education lower priority in their budgets; pension plans for government workers now grant reduced and sometimes zero net benefits to new, younger hires; and homeownership subsidies post-recession increasingly favor the haves over the more risky have-nots.

Maybe, more than just maybe, it’s time to think about investing in the young.

Getting the Facts Straight on Retirement Age

Posted: March 12, 2013 Filed under: Aging, Columns, Economic Growth and Productivity, Income and Wealth, Race, Ethnicity, and Gender 16 Comments »On the front page of the Washington Post on March 11, 2013, Michael Fletcher connects the different life expectancies of the poor and rich to the debate over whether Social Security should provide more years of retirement support as people live longer. He mistakenly leaves the impression that adjusting the retirement age for increases in life expectancy hurts the poor the most. In fact, such adjustments take more away from the rich. Let me explain how.

Suppose I designed a government redistribution policy that increases lifetime Social Security benefits by $200,000 for every couple with above-average income that lives to age 62. For every couple with below-average income that reaches age 62, my program would increase benefits by $100,000.

Does this sound like a good policy? Well, that’s exactly what Social Security has done by providing all of us with increasing years of retirement support. People retiring today get many, many more years of Social Security benefits than those retiring when the system was first created. And, the primary beneficiaries are the richer, not the poorer, among us. Throwing money off the roofs of tall buildings would be a more progressive policy, since the poor would likely end up with a more equal share.

Why, then, do some Social Security advocates oppose increasing the retirement age? Because the $100,000 in my example could mean proportionately more money for the poor. For instance, it might add one-tenth to their lifetime earnings (of, say, $25,000 a year for 40 years of work, or $1 million over a lifetime), while the $200,000 to rich individuals might add only one-fifteenth to their lifetime earnings. As it turns out, even this assumption isn’t correct, but let’s assume for the moment it is.

Why would we want to redistribute that way? Following that logic, we should have protected the jobs of all the Wall Street bankers after the recent crash because their wages represented a smaller share of their income than the wages of poorer workers providing support services. Or perhaps we should provide $5,000 of food stamps to those making more than $50,000 and $3,000 of food stamps to those making $20,000; after all, the latter would still get proportionately more.

As it turns out, however, more years of retirement benefits don’t benefit the poor proportionately more than the rich. Yes, the poor have lower life expectancies, but other elements of Social Security offset this factor. A greater share of the poor doesn’t make it to age 62, so a smaller share of them benefit from expansions in years of retirement support. More importantly, those who are poorer are more likely to receive disability payments that aren’t affected one way or the other by the retirement age; hence, again, a significantly smaller share of them benefit from more retirement years. Other regressive elements such as spousal and survivor benefits also come into play for reasons I won’t further explain here. Empirically, these various factors add up in such a way that increases in years of benefits help those who are richer and those who are poorer in ways roughly proportionate to their lifetime incomes.

Setting these disputes aside, the higher mortality rate of the poor at each age does raise many legitimate policy issues. Recipients who stopped smoking a couple of decades ago, for instance, have been rewarded with more and more years of retirement benefits. This, along with many other features of Social Security, such as the design of spousal benefits already noted, does mean that the system is a lot less progressive than most believe.

The more fundamental issue, then, is whether we should better protect those with low-to-average wages during their lives. I believe we should but through better-targeted mechanisms, such as minimum benefits, progressive adjustments to the benefit formula, wage supplements to low-wage workers, and other devices that don’t spend most of the program’s funds on ever more years of retirement for those who are richer.

Yet another reason to worry about the retirement age is that the failure to adjust over time—a couple retiring today at 62 can now expect about 27 years of benefits—has meant larger shares of payments go to those closer to middle age, in terms of remaining life expectancy. Almost every year, a smaller share of payments goes to those who are truly old and more likely to need assistance.

In sum, the recent widening gap in life expectancy, likely due to such factors as differential rates of cigarette smoking, deserves serious attention. But let’s not pretend that throwing money off the roof, or providing more years of retirement support to the non-disabled who make it to age 62, addresses the core issue. There are better ways to compensate than converting a system originally designed to protect the old into one offering middle-age retirement to everyone.

Creative Ways Around a Blunt Sequester

Posted: February 27, 2013 Filed under: Columns, Income and Wealth, Taxes and Budget 5 Comments »I would like to offer two simple plans, one for Republicans and one for Democrats, to avoid a blunt, across-the-board sequester with no realistic assessment of priorities. Each plan gives both parties something they want without abandoning their core principles. Each also strengthens the party making the proposal by putting the other one on the spot if it fails to move toward a moderate compromise.

First, Republicans. They should offer to empower the president, within fairly broad limits, to reallocate the direct spending cuts required by sequester and include entitlements in the offer. Yes, they would cede some power over a relatively moderate share of total spending, but they would retain their primary goal: forcing Democrats to tackle the spending side of the budget.

Next, Democrats. They should replace their demand that the sequester include tax increases with a simpler demand that the rich pay a fair share of any burden. Yes, they would give up their requirement of balancing tax increases with spending cuts, but they would retain their more basic goal: maintaining or enhancing progressivity.

To understand why these strategies would work, we have to go back to the root causes of the impasse. Both parties are fiercely fighting to compel the other one to ask the middle class for the inevitable—to give up something, at least long term, to restore reasonable balance to the budget. Each party considers it political suicide to take the lead itself. Just think back to the presidential campaign, when each candidate indicated support for Medicare cuts, only to be viciously attacked by the other.

At the same time, both parties feel trapped and confused by years of mutual dissembling about subsidies that are put into the tax code.

Given that the American Tax Relief Act increased tax rates just last month, neither party is suggesting higher taxes. The debate now is over the tax base. Republican, Democratic, and independent economists all agree that subsidies in the tax code can be made to look just like direct spending. Therefore, any reasonable debate should be over whether all subsidies and spending programs work well and are worth every dime they cost, or whether they should be reformed—not on which side of the ledger they sit.

For Republicans, the subtext is that direct spending also needs to be tackled, and much of that direct spending lies in so-called mandatory or entitlement spending, which occurs automatically with no new vote required by Congress. The push to enact yet more “tax increases,” just after tax rate were raised, they consider unfair and imbalanced.

For Democrats, the subtext is that the rich have made out quite well in recent decades, so they should bear a significant portion of any deficit reduction. Excluding tax subsidies, which tend to be a bit more top-heavy and favor taxpayers with above-average incomes, they consider unfair and imbalanced.

As I noted, to an economist of any stripe, deciding which programs to fix according to the label we place on them—direct spending or tax subsidy—is silly. But this logic belies a long history where both Democrats and Republicans were quite happy increasing tax subsidies since they could then claim smaller government (through lower taxes) when they were actually increasing the scope of government activity (through more interference, along with deficits or higher tax rates to support the subsidies). Now that we have to cut back on automatic growth in direct spending, or tax subsidies, or (most likely) both, it’s harder to change the terms of the debate.

In truth, Republicans should be just as happy cutting back on tax subsidies as on direct spending, as both mean less government interference in the economy. By the same token, Democrats should be just as happy with direct spending cuts as with cuts in tax subsidies. Since Democrats, too, end up with smaller government either way, they should focus on progressivity, not the more semantic debate over cuts in tax subsidies versus direct subsidies.

That’s where my compromise proposals come in. If Republicans would simply empower the president to reallocate the spending cuts, then the bluntness of the sequester would be eliminated. Yes, they would be giving up some power, but come on, they control only one house of Congress. Look how they came out of the last debate, with only tax rate increases and a bloody nose to boot. Forcing the president to choose also enables Republicans to run later on how they would have chosen better. And if the president really cares about progressivity, he should want to extend those cuts to entitlements, many of which also provide more benefits to the rich than the poor.

As for Democrats, why not aim their sights at their real target: progressivity? If the Republicans would allocate spending cuts as progressively as the Democrats could ever expect tax base increases to come out, then they, too, will have achieved their principal objective. Moreover, if Republicans couldn’t balance the burden of deficit reduction with spending cuts alone, they would be forced to admit that they have to go to the tax code to search for additional options, including tax subsidies.

A similar type of compromise might also be used to change the timing of the sequester, an issue beyond the scope of this brief column.

Simply put, to move beyond budgetary impasses, each party must figure out what it can give up to get what it really wants, while putting the other party on the spot for not responding to a reasonable offer of compromise. Neither of my suggestions is perfect, by any means, but I think either one or both could remove the bluntness of the sequestration.