IRS and the Targeting of the Tea Party and Other Groups

Posted: May 14, 2013 Filed under: Columns, Nonprofits and Philanthropy, Taxes and Budget 1 Comment »To help clarify whether IRS incorrectly, unfairly, or illegally targeted the Tea Party and other conservative groups, here are the answers to a few basic questions.

1. Is it improper for IRS to target specific groups?

Almost every contact the IRS makes with select taxpayers derives from targeting. Because its resources are constrained, the IRS conducts only limited audits, examinations, or requests for information. For instance, if you give more than the average amount to charity, you’re more likely to be audited since there is more money at stake. If you run a small business, you have a greater ability to cheat than someone whose income is reported to IRS on a W-2 form. The only way the IRS can enforce compliance at a reasonable administrative cost is by targeting.

This is especially true for the tax-exempt arena. Because audits yield little or no revenue, the IRS tax-exempt division examines very few organizations. Therefore, the IRS must use some criteria to “target” which tax-exempt organizations to approach.

2. Does the IRS discriminate?

Picking out which organizations or taxpayers to examine meets the definition of statistical discrimination. Firms do this when they consider only college graduates for jobs; political parties do this when they offer selective access to their supporters. Discrimination is wrong when it implies unequal treatment under the law, such as when unequal punishment is meted out for the same crime, or when people of color have less access to the mortgage market.

3. Why then did IRS say it erred in targeting Tea Party and other organizations?

We don’t have all the data yet but organizations with a strong political orientation have a higher probability of pushing the borderline for what the law allows. The groups at the center of this controversy generally applied for exemption under IRS section 501 (c)(4) which requires, among other things, that its primary purpose cannot be election-related and cannot overtly support political candidates.

However, the IRS could have identified election-related activity as a practice worthy of extra attention without specifying “tea party” or similar labels to identify such organizations. Had it done so, it might not be facing a problem now.

IRS apparently initially thought it was just using these labels as a shortcut for such an identification. Had it been engaged early on, the national office might have been quicker to warn against this practice since it would tend to identify more Republican organizations than Democratic groups with similar motives. Who decided what when is still under investigation.

Remember IRS was under pressure to examine those c(4) organizations after applications grew rapidly in the wake of the Supreme Court’s 2010 Citizens United decision. If IRS waits until after an election, it’s generally too late to make any difference.

4. Why did IRS start with the exemption process rather than wait and see how the organizations behaved?

Because IRS audits so few tax-exempt organizations, noncompliance is a major problem. But often noncompliance is inadvertent. Organizations trying to do “good” fail to understand legal technicalities or why IRS should be worried about them at all. If the IRS can get these organizations to comply with the rules from the start, it has a better chance of minimizing future problems.

5. Well, then, why the heck is IRS even in this game in the first place?

A question asked by many. Unlike some other nations with charities’ bureaus or other government regulatory agencies, tax-exempt organizations in the U.S. are monitored mainly by IRS at the national level and the state attorneys general at the state level. The IRS efforts generally derive from the Congressional requirement that charitable dollars (for which there are deductions and exemptions) go mainly for charitable purposes and not others such as electioneering.

6. But c (4) or social welfare organizations don’t benefit from the charitable deduction, so why don’t those with political orientation just operate without tax exemption or c(4) status?

They could, but the tax exemption provides several benefits. The least important may be non-taxation of income from assets since many of these organizations don’t have that much in the way of assets to begin with. However, many contributors interpret (often incorrectly) tax exemption to mean that the organization has satisfied legal hurdles, thus making it easier to raise money. Some c(4) organizations are closely connected to charities or c(3) organizations that can accept charitable contributions, and sometimes there’s a synergy between the two. My colleague Howard Gleckman reminds us that c(4)s quickly became favored over an alternative “527” tax-exempt political designation because the former does not need to reveal its donors. Finally, tax exemption provides an easy way to insure that any temporary build-up of donations in excess of payouts is not interpreted as taxable income to the organization or its contributors.

7. What will be the end result of this flap?

Success at agencies like IRS is often measured by their ability to stay out of the news rather than on how well they do their job. I’m guessing this episode will only will increase the bunker-like incentives within the organization. It would be good if Congress used this as an opportunity to figure out how better to monitor tax-exempt organizations, or whether IRS has the capability under existing laws, but that isn’t likely to happen.

Extending the Charitable Deduction Deadline to Tax Day

Posted: March 19, 2013 Filed under: Nonprofits and Philanthropy, Shorts, Taxes and Budget 2 Comments »Extending the charitable deduction deadline is a move with precedent: the government has used it to encourage giving following a natural disaster. President Barak Obama signed a provision allowing charitable donations toward the Haiti earthquake made from January 11 to March 1, 2010, to be deducted on 2009 tax returns. President George W. Bush signed a similar law allowing donations for tsunami relief made through January 31, 2005, to be deducted in 2004.

These provisions aim to increase giving at a time when need is critical. In reality, such temporary laws have limited effect because many do not know about these one-off incentives.

Consider instead the marketing possibilities of more permanent incentives to allow charitable deductions made by April 15, aka tax day, to be applied to the previous year’s tax returns.

By making what has frequently been a temporary measure into a permanent law, you eliminate the problem of trying to publicize brief windows of opportunity. Instead, people would come to expect that at filing time they would consider how much they would save by giving to charity.

Evidence suggests that, as in other facets of life, people are prone to making their decisions concerning giving at the last minute. The Online Giving Study finds that 22 percent of online donations are made on the last two days of the December, the last possible moment to claim a tax deduction for that year. Presumably this effect could be magnified if taxpayers were able to add to their charitable giving up until the last two days before they filed their tax returns.

Think of what such tax software companies as TurboTax or H&R Block could do by showing taxpayers directly how donating an extra $100 or $1,000 to any charity would lower their taxable income. The companies could even process the donation immediately through a credit card. If such a measure were enacted, I predict some foundations and charitable-sector collaborative organizations would immediately engage software tax preparation companies, other tax preparers, banks, and online giving organizations to figure out the best way to market this opportunity to the public.

This incentive would be by far among the most effective that Congress has ever provided in almost any arena, including existing charitable incentives. Why? Essentially, the revenue loss to the government is only 30 cents or so (the tax saving) for every additional dollar of charity generated. If people don’t give more, there are no losses, outside some slight timing differences. This is triple or more the estimated effectiveness of charitable giving incentives overall.

Marketing experts immediately grasp windows of opportunity. Back-to-school sales take place in September when families are thinking about school, grocery store advertisements near the weekend when more people do their shopping, Caribbean cruises in the winter when people are cold. The very best time to advertise charitable tax saving is when people file their tax returns.

This change would also add an element of certainty. Not knowing their income and tax rates for the existing year until it is over, people can only guess at the tax effect of any contribution they make to charity. When filing taxes, they can calculate exactly how much tax an additional donation would save.

A permanent law would also encourage all areas of giving instead of only the specific causes picked by Congress. Such targeted opportunities don’t necessarily increase people’s total donations: people are more likely to switch which charity they give to, not give more overall, when Congress highlights a particular charity.

In exploring this option for a number of years, I can find only one significant concern: the increased complication that is always induced by offering people choices (the actual tax-saving calculation, as noted, is actually simpler for many). Would people, for instance, mistakenly report their contributions twice, once for the past year and once for the current year? Would charities have trouble handling an extra checkbox in which taxpayers indicate in what year the contribution was intended?

If one is really interested in making the incentive better, this complication obstacle is easy to overcome. There are options here.

One would be to improve information reporting to IRS on charitable gifts. Only gifts for which charities give formal statements to individuals and the IRS itself could be made eligible. Noncash gifts might be limited in this case to those for which a formal valuation is provided to the taxpayers or, at least initially, excluded altogether. The information reports might only apply to those contributions over $250 for which charities are already required to provide statements to individuals. If charities don’t want to participate, they don’t have to.

Another, lesser bargain would be to experiment first only with online contributions for which software companies could send a report to the individual, charity, and IRS alike (this could include online checks for those banks and other institutions, not just credit card companies, who would be willing to participate). Other compromises along these lines are possible, and some of them on net are likely to improve compliance because of the integrated information system—a win-win strategy.

In separate testimony, I have offered a number of ways that this type of proposal could be incorporated into broader tax and budget reform so charitable giving is increased without any loss in revenues to the government.

With the United States still locked in a recession and the government cutting back its own efforts, what better time is there to encourage greater charitable giving?

Video on the Ways and Means Committee’s Hearing on Tax Reform and Charities

Posted: February 15, 2013 Filed under: Nonprofits and Philanthropy, Shorts, Taxes and Budget Leave a comment »See a 2-part video of testimony and discussions before the Ways and Means Committee on “Tax Reform and Charities.” To get a sense of Ways and Means members’ views on the related policy issues, the first panel, with the following presentations, in order: myself; Kevin Murphy, Chair, Board of Directors of the Council on Foundations; David Wills, President of the National Christian Foundation; Brian Gallagher, President & CEO of United Way Worldwide; Roger Colinvaux, Professor of Catholic University DC Law School and adviser for the Tax Policy and Charities project at the Urban Institute; Eugene Tempel, Dean of the Indiana University School of Philanthropy; Jan Masaoka, CEO of California Association of Nonprofits. Copies of all testimonies can be found online.

See also our Tax Policy and Charities website for many related studies and data.

The first video begins after about 33 minutes of set up and administrative matters:

In addition, the Urban Institute will be hosting a conference on “The Charitable Deduction: A View from the Other Side of the Cliff” on Thursday, February 28, 2013. Registration is now open.

Tax Reform and Charitable Contributions

Posted: February 14, 2013 Filed under: Nonprofits and Philanthropy, Shorts, Taxes and Budget 1 Comment »The debate over the charitable deduction mistakenly pits those who acknowledge that the government needs to get its budget in order against those who recognize the extraordinary value of the charitable sector. The tax subsidy for charitable contributions should be treated like any other government program, examined regularly, and reformed to make it more effective. In fact, the charitable deduction can be designed to strengthen the charitable sector and increase charitable giving while costing the government the same or even less than it does now.

What’s the trick? Take the revenues spent with little or no effect on charitable giving, and reallocate some or all of them toward measures that would more effectively encourage giving.

For example, to increase giving Congress can do any or all of the following:

- allow deductions to be given until April 15 or the filing of a tax return;

- adopt the same deduction for non-itemizers and itemizers alike;

- consider proposals to ease limits on charitable contributions, such as allowing contributions to be made from individual retirement accounts (IRAs) and allowing lottery winnings to be given to charity without tax penalties;

- raise and simplify the various limits on charitable contributions that can be made as a percentage of income;

- reduce and dramatically simplify the excise tax on foundations; and

- change the foundation payout rule so it does not encourage pro-cyclical giving.

Congress can more than pay for these changes with little or no reduction in revenue if it would:

- place a floor under charitable contributions so only amounts above the floor are deductible (economists generally believe that some base amount of contributions would be given regardless of any incentive, thus floors have less effect on giving);

- provide an improved reporting system to taxpayers for charitable contributions;

- limit deductibility for in-kind gifts where compliance is a problem or the net amount to the charity is so low that the revenue cost to government is greater than the value of the gift made; and

- to help the public monitor the charitable sector, require electronic filing by most or all charities.

Budget and tax reform are now unavoidably intertwined. When it comes to the tax law concerning charitable contributions, we can do a lot to make our subsidy system more effective from both a fiscal and a charitable sector standpoint.

For more details, see my congressional testimony for today’s hearing on “Tax Reform and Charitable Contributions” before the Committee on Ways and Means.

High-Income Charitable Giving and Higher Education

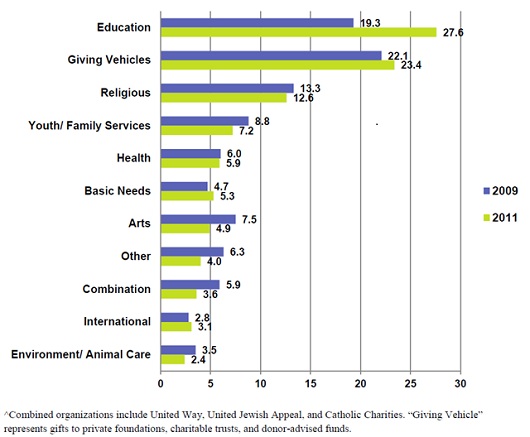

Posted: January 17, 2013 Filed under: Nonprofits and Philanthropy, Shorts 2 Comments »If reforms to the charitable deduction decrease giving among high-income donors, certain types of charities will be affected more than others. As the graph below from a 2012 Bank of America Study indicates, high-income donors give mostly to education, followed by organizations such as trusts and foundations that primarily support other nonprofits (referred to as giving vehicles). Thus, changes to tax law affecting only high-income taxpayers would disproportionately affect donations to educational institutions. However, the relationship isn’t as linear as this figure suggests. Take international organizations, for instance. They receive fewer donations from high-income givers than health organizations, but they rely on those donations more; many health organizations, such as hospitals, receive substantial amounts in fees for service. International organizations also may be among the primary recipients of grants from giving vehicles.

Distribution of High Net Worth Giving: More to Education

Source: 2012 Bank of America Study of High Net Worth Philanthropy.

Note: High net worth includes households with incomes greater than $200,000 and/or net worth more than $1,000,000 excluding the monetary value of their home.

For more interesting data, visit the Tax Policy and Charities project.

Ten Questions on Cutting Back Itemized Deductions

Posted: December 11, 2012 Filed under: Columns, Nonprofits and Philanthropy, Taxes and Budget 1 Comment »- Why are itemized deductions getting so much more attention in budget negotiations than other tax breaks?

- Itemized deductions show up on tax returns, so they are among the most visible of all tax subsidies or adjustments. Other tax breaks tend to be harder for politicians and the public to understand.

- Why do most proposals to limit itemized deductions focus on higher-income taxpayers?

- Politicians run from telling the middle class that they get most government benefits, pay most government taxes, and eventually will have to get less and pay more to help get our budget under control. Meanwhile, Democrats want to increase taxes on higher-income taxpayers, but Republicans don’t want to increase tax rates. Itemized deductions for higher-income taxpayers are among the few options that fit amidst these limitations.

- How much of the revenue lost from all tax expenditures or subsidies comes from the itemized deductions being discussed?

- By one estimate, individual tax expenditures will cost the government about $1.2 trillion a year in 2015. If other policies aren’t changed, itemized deductions will cost about $180 billion by then, or about 15 percent of the total. Itemized deductions taken by those making more than $200,000 as individuals or $250,000 for couples (the president’s proposed level for starting to deny deductions) make up about 8 percent of total individual tax expenditures, or about $100 billion. See this graph on the revenue gained from various tax proposals and how this compares to the deficit.

- How many taxpayers would be affected by these limits, and how much revenue would be raised?

- Many proposals to cut back on itemized deductions affect only about 2 or 3 percent of taxpayers and would raise $15–$60 billion in 2015, compared with a deficit of close to $900 billion under current policies. A tougher cap would raise more revenue but affect more taxpayers. Obviously, a lot depends upon the actual legislation.

- Are limits on other tax expenditures being discussed?

- Yes. Some proposals would increase the tax on dividends and capital gains back to its level before the Bush-era tax cuts. Some would cap the exclusion allowed to employees buying health insurance from their employers. The president has proposed a number of other, generally smaller cutbacks, including removing tax breaks for employee contributions to 401(k) and similar retirement plans. Most of these have gotten less attention.

- What’s the appeal of across-the-board limits on itemized deductions?

- Politicians think various constituencies will less strongly oppose across-the-board limits that don’t single out any particular provision. To some supporters, these limits appear to attack interest groups even-handedly.

- But do they attack various interests even-handedly?

- No. Across-the-board limits would hit charitable deductions the hardest since people can quickly offset the tax increase by giving less to charity. State and local tax deductions, on the other hand, are less discretionary. Also, higher-income taxpayers give a large portion of all charitable contributions, so that sector is hit worse than, say, housing, where mortgage interest deductions are more concentrated in a middle class usually unaffected by the proposal.

- Do different caps affect behavior differently?

- Yes. An overall limit of $50,000 on itemized deductions effectively gives a 0 percent subsidy for, say, an extra dollar of home mortgage interest above that limit. Other proposals simply limit the subsidy to 25 cents or 28 cents but generally place no extra bounds (beyond current law) on how many dollars can be deducted.

- What are the drawbacks of overall deduction caps?

- Some deductions, just like government programs, are more justifiable than others. For instance, society may want to encourage charitable giving but not want to encourage debt to buy bigger homes or second homes. Almost all tax experts—left, right, and independent—feel that the best way to reform government programs, whether hidden in the tax code or not, is to tackle each one on its own merits.

- How does tackling a particular incentive on its own merits work?

- Consider the itemized deduction for charitable contributions. Instead of discouraging giving that might be quite desirable societally, policymakers could focus on lowering deductions for items with low compliance rates. For example, the deductions that people claim for donating used clothes seem significantly larger than the value the charities derive from such donations. Congress could also restrict subsidies for the first dollars of giving, such as the first 1 or 2 percent of income—amounts taxpayers would likely give in absence of any incentive. The incentive would then remain for the more discretionary giving above that floor. Finally, some of the revenue gained could then be spent where giving would be more responsive to the incentive. For instance, Congress could allow taxpayers to take deductions for contributions made up until they file their tax returns, or it could provide a deduction above a floor to those who currently don’t itemize.

In effect, Congress could strengthen its fiscal posture and the charitable sector at the same time. The same argument could be made for allocating homeownership subsidies better. In sum, blanket rules are arbitrary when applied to programs of different effectiveness and merit.

Cutting Back on Charitable Incentives: The Case for Automobiles

Posted: November 30, 2012 Filed under: Nonprofits and Philanthropy, Shorts, Taxes and Budget 2 Comments »With Congress and the President seriously considering proposals to reduce various tax subsidies, the charitable deduction has come into play. As opposed to proposals that cut back on giving across the board, it may be worthwhile to consider other alternatives. This short note indicate some evidence on what happened when Congress recently cut back on allowances for donations of automobiles because of perceived abuses.

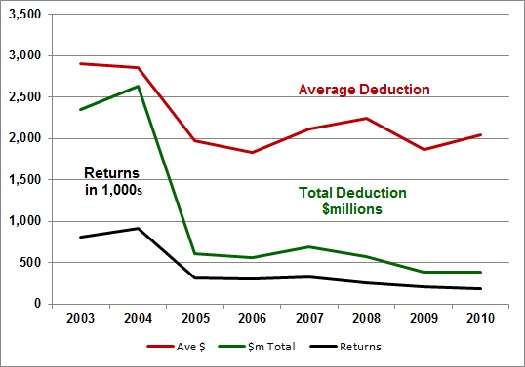

In 2003, a GAO study found suspiciously large unsubstantiated deductions for donations of vehicles to charity. In response to evidence that donors were claiming well in excess of the value of these deductions to charities, Congress in 2004 limited the deduction for vehicles worth over $500 to the charity’s actual selling price of the vehicles. It also required donors to attach a statement of sale indicating that it was “sold in an arm’s length transaction between unrelated parties” or a written statement that the charity would use the donated car in its programs. Higher deduction amounts were still allowed for charities that used the vehicles directly, as opposed to selling them.

The graph below shows that tax deductions claimed for vehicles fell sharply after enactment of this law.

Source: Gerald Auten, Department of Treasury.

For more information on noncash contributions generally, see “Noncash Charitable Contributions: Issues of Enforcement” which includes postings on noncash charitable contributions, an area worth $44 billion to nonprofit organizations in 2010.

Charities Making Payments in Lieu of Property Taxes

Posted: October 26, 2012 Filed under: Nonprofits and Philanthropy, Shorts, Taxes and Budget 11 Comments »Urban Institute recently held a conference on “State and Local Budget Pressures: The Charitable Property-Tax Exemption and PILOTs” which explored how increasing fiscal pressure on governments on the state and local level has led governments to re-examine which charities should be exempt from property taxes, and in some cases to ask for Payments in Lieu of Taxes (PILOTs), a voluntary payment of portion of their exempt property taxes from nonprofits.

The first panel “The Current Landscape” looked at costs and benefits of the current exemption; the second “Focus on Eds and Meds” took a closer look at the largest and most controversial beneficiaries of the exemption, nonprofit hospitals and colleges and universities; and the third “Negotiated Payments in Lieu of Taxes as Wave of the Future?” debated the use of Payments in Lieu of Taxes (PILOTs) and discussed how a well-designed PILOT program could be created.

The graph below, from a presentation by Daphne Kenyon of the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, highlights the increasing prevalence of PILOTs as local governments seek new sources of revenue.

States with Jurisdictions Collecting PILOTs

Daphne Kenyon. 2012. “Payments in Lieu of Taxes: Balancing Municipal and Nonprofit Interests.” Urban Institute conference on “State and Local Budget Pressures: The Charitable Property-Tax Exemption and PILOTs,” on May 21, 2012 at the Urban Institute.

For more details I recommend reading the brief based off the conference, which describes the mechanics of governments asking for voluntary taxes from nonprofits in more detail, and gives an overview of the debate over such payments.