Testimony on Drivers of Intergenerational Mobility and the Tax Code

Posted: July 10, 2012 Filed under: Children, Income and Wealth, Shorts, Taxes and Budget 2 Comments »On July 10, 2012, I testified before the Senate Finance Committee on “Mobility, the Tax System, and Budget for a Declining Nation,” available online here. Below is a shorter summary of my testimony.

Nothing so exemplifies the American Dream more than the possibility for each family to get ahead and, through hard work, advance from generation to generation.

Today mobility across generations is threatened by three aspect of current federal policy:

- a budget for a declining nation that promotes consumption ever more and investment, particularly in the young, ever less;

- relatively high disincentives to work and saving for those who try to move beyond poverty level income; and

- a budget that generally favors mobility for those with higher incomes, while promoting consumption but discouraging mobility for those with lower incomes.

Let me elaborate briefly.

First, in many ways, we have a budget for a declining nation.

Even if we would bring our budget barely to a state of sustainability—a goal we are far from reaching right now—we’re still left with a budget that allocates smaller shares of our tax subsidies and spending to children, and ever-larger shares to consumption rather than investment.

Right now the federal government is on track to spend about $1 trillion more annually in about a decade. Yet federal government programs that might promote mobility, such as education and job subsidies or programs for children, would get nary a dime. Right now, these relative choices are reflected in both Democratic and Republican budgets.

Second, consider that one of the main ways that part of the population rises in status relative to others is by working harder and saving a higher portion of the returns on its wealth. Discouraging such efforts can reduce the extent of intergenerational mobility.

One way to look at the disincentives facing lower-income households is to consider the effective tax rates they face, both from the direct tax system and from phasing out benefits from social welfare programs. After reaching about a poverty level income, these low- to moderate-income households often face marginal tax rates of about 50 or 60 percent or even 80 percent when they earn an additional dollar of income.

Third, in a study I led for the Pew Economic Mobility Project, we concluded that a sizable slice of federal funds—about $746 billion or $7,000 per household in 2006—did go to programs that arguably try to promote mobility. Unfortunately 72 percent of this total comes mainly through programs such as tax subsidies for homeownership and other saving incentives that flow mainly to middle- and higher-income households. Moreover, some of these programs inflate key asset prices such as home prices. That puts these assets further out of reach for poor or lower-middle-income households, or young people who are just starting their careers. Thus, programs not only neglect the less well-off, they undermine their mobility.

Finally, a note about some current opportunities. Outside education and early childhood health, if Congress wishes to promote mobility of lower-income households, as well as protect the past gains of moderate- and middle-income households that are now threatened, almost nothing succeeds more than putting them onto a path of increasing ownership of financial and physical capital that can carry forward from generation to generation.

Two opportunities, largely neglected in today’s policy debates, may be sitting at our feet.

First, rents have now moved above homeownership costs in many parts of the country. Unfortunately, we seem to have adopted a buy high, sell (or don’t buy) low homeownership policy for low- and moderate-income households.

Second, pension reform is a natural accompaniment and add-on to the inevitable Social Security reform that is around the corner.

I hope you will give some consideration to these two opportunities.

In conclusion, the hard future ahead for programs that help children, invest in our future, and promote mobility for low- and moderate-income households does not necessarily reflect the aspirations of our people or of either political party.

Testimony on Marginal Tax Rates and Work Incentives

Posted: July 9, 2012 Filed under: Economic Growth and Productivity, Income and Wealth, Shorts, Taxes and Budget 2 Comments »On June 27, 2012 I testified before the House Subcommittees on Human Resources and Select Revenue Measures on the interaction of various welfare and tax credit programs and work incentives. My full testimony, “Marginal Tax Rates, Work, and the Nation’s Real Tax System” can be found here, and the entire hearing can be watched online here. Below is a shorter summary of my remarks.

The nation’s real tax system includes not just the direct statutory rates explicit in such taxes as the income tax and the Social Security tax, but the implicit taxes that derive from phasing out of various benefits in both expenditure and tax programs. These “expenditure taxes,” as I call them, derive largely from a liberal-conservative compromise that emphasizes means testing as a way of both increasing progressivity and saving on direct taxes needed to support various programs. Although low- and moderate-income households are especially affected, you can’t turn around today without spotting these hidden taxes in Pell grants, the AMT, and in dozens, if not hundreds, of programs.

At the Urban Institute we have done quite a bit of work on calculating these rates. One case study we examined was a single parent with two children in Colorado in 2011, to find the maximum benefits for which such a person may be eligible and how they phase out as income increases. (Our net income change calculator (NICC) is now available on the WEB site and can demonstrate tax rates for families in a variety of circumstances in every state.) Rates are low or negative up to about $10,000 to $15,000 of income. Thereafter, they rise quickly. We also looked at the effective tax rate for a household whose income rises from $10,000 to $40,000, and found that income and payroll taxes take away about 30 percent of earnings. The phase out of universally available benefits such as EITC and SNAP or food stamps raises the rate to about 55 percent, and the household getting maximum subsidies, such as welfare and housing, sees a rate of about 82 percent. What used to be called a poverty trap has now moved out to what Linda Giannarelli and I have labeled the “twice poverty trap.” That is, the high rates especially hit households that earn more than poverty level incomes.

Many studies have attempted to show that the effect of these rates on work, and the results are mixed. Work subsidies such as the EITC generally encourage labor force participation but may tend to discourage work at higher income levels, particularly for second jobs in a family or moving to full time work. Design matters greatly. For instance, Medicaid will discourage work among the disabled more than a subsidy system such as the exchange subsidy adopted in health reform; on the other hand, health reform will probably encourage more people to retire early. For the same amount of cost, a program that requires work will indeed lead to more work than one that does not. EITC and welfare reform have done better on the work front than did AFDC.

Other consequences must be examined. Means testing and joint filing have resulted in hundreds of billions of dollars of marriage penalties for low and middle income households. Not marrying is the tax shelter for the poor. Many programs do help those with special needs, although they vary widely in their efficiency and effectiveness. There is some evidence that well-developed programs can improve behaviors such as school attendance and maternal health. At the same time, long-run consequences are often hard to estimate.

Just as a classic liberal-conservative compromise got us to this situation, so might it require a liberal-conservative consensus get us out of it. Among the many approaches to reform are (a) seeking broad-based social welfare reform rather than adopting programs one-by-one with multiple phase-outs, (b) starting to emphasize opportunity and education over adequacy and consumption; (c) putting tax rates directly in the tax code to replace implicit tax rates, (d) making work an even stronger requirement for receipt of various benefits, (e) adopting a maximum marginal tax rate for programs combined, and (f) letting child benefits go with the child and wage subsidies go with low-income workers rather than combining the two.

Declines in Wealth and Declines in Income

Posted: June 26, 2012 Filed under: Economic Growth and Productivity, Income and Wealth, Shorts 1 Comment »The press recently had a field day reporting the decline in wealth from 2007 to 2010, as measured by a recently released Survey of Consumer Finances. Be careful interpreting those results. A decline in the valuation of wealth does not necessarily mean any decline in collective well-being or consumption in a society.

Think of a decline in the price of gold. Society doesn’t necessarily consume any less of anything, and the loss for the gold seller is a gain for the gold buyer. More relevant to the current crisis, take the value of a house. It doesn’t produce any fewer services just because it sells for less. And the buyer gains what the seller loses. A retiree’s hope for selling and then spending down those assets in retirement may be reduced, but his children’s earnings go a lot further if they decide to buy a house.

There are, of course, real and agonizing losses from a recession. They largely come from the decline in output of society and of the corresponding income of its citizens. There are too many unemployed and underemployed resources, both people and capital. When a decline in society’s aggregate wealth reflects a reduction in the collective value of all the future things it can produce or buy—for instance, because factories produce less—then there are total net losses that are never recovered. Even here, however, one must distinguish between when the decline in wealth valuation occurs and when the losses to society really take place. Greece’s economy, for example, was long on a downhill curve, which the markets finally realized. In fact, if the reform effort succeeds, Greek citizens may end up with a more, not less, wealthy economy than they had when stocks and bonds started tumbling downward.

Are French and Greek Election Results That Surprising?

Posted: May 9, 2012 Filed under: Economic Growth and Productivity, Shorts Leave a comment »I’m fascinated by articles finding any mystery in the recent French and Greek elections. Do the results prove or disprove the sagacity of recent austerity drives in European budgets? Do they presage the resurgence of socialist initiatives in France? Do they sound the death knell for established political parties in Greece?

Hardly. The French and Greek governments were only the latest two of perhaps a dozen to fall in the past few years. Some count Barack Obama’s election as president of the United States in 2008 and the Republican Party’s recapture of the House of Representatives a mere two years later as similar political upheavals.

Throughout the developed world we are seeing the electorate respond to two powerful forces. The first: the Great Recession and its aftermath. In the wake of this severe economic downturn, no political party is safe, and public opinion bounces from left to right to everywhere in between. Voters are mainly rejecting whoever is in power, with the source of popular frustration switching from the recession to the lack of a better recovery.

The second, less obvious force: a new fiscal era whose details have yet to be resolved. Since World War II, politicians have been able to operate mostly on the give-away side of the budget, with legislation dominated by tax cuts and spending increases. Now these generous governments have shot their wads, giving away not just current resources but any that ever will be available—and then some. That’s tough. Politicians usually do not run on what they are going to ask for from us, as opposed to what they are going to give us. And we voters punish politicians when they try to either pay for all those past give-aways or pare them back.

These problems are not the left-right issues of the 20th century. Political parties themselves must redefine themselves for this new era, and, since they haven’t figured that out, their internal upheavals match their external ones in dealing with the voter.

Expect the political turmoil to continue.

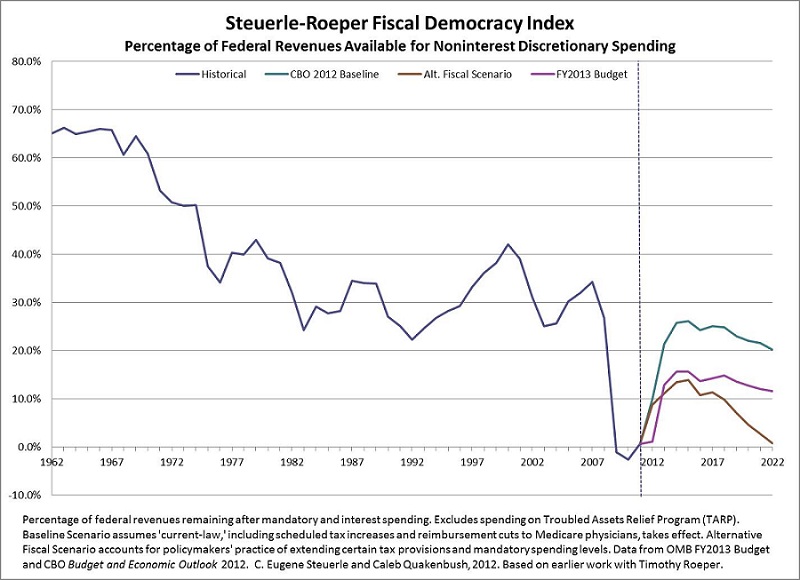

Fiscal Democracy Index: An Update

Posted: May 4, 2012 Filed under: Shorts, Taxes and Budget 6 Comments »This chart provides an update on percent of federal revenue available for discretionary spending over time.

Eugene Steuerle and his colleague, Tim Roeper, have developed a “fiscal democracy index” to document the fall in the fiscal freedom of our policymakers in recent years and into the future. To calculate the index, Steuerle and Roeper measured the extent to which past and future projected revenues are already claimed by the permanent programs already in place (including interest payments on the debt). The fiscal democracy index is neutral politically, favoring neither a liberal or conservative agenda, in the sense that it falls with both rising commitments from the past and reduced revenues. It fell into negative territory for the first time in history in 2009 – meaning that revenues were already falling short of the built-in spending of permanent programs – and it will return to negative territory soon if Congress does not change current entitlement and tax policies. Even reducing annual non-entitlement spending to zero – thus, ending education, transportation, housing, defense, and most other general government programs – will do little to alter the downward path of the index other than reduce some interest costs temporarily. That means that future generations will have no additional revenues to finance their own new priorities, and they will actually have to raise new revenues or cut other spending just to finance the expected growth in existing programs.

Fiscal democracy will be a central concept of Gene’s forthcoming book with Larry Haas.