Civil Rights and Economic Mobility

Posted: September 5, 2013 Filed under: Columns, Economic Growth and Productivity, Income and Wealth, Race, Ethnicity, and Gender 1 Comment »The 50th anniversary of “the March on Washington”—so famous and, in many ways, so successful that “the” is sufficient to define it—brought forth a gusto of stories about what had been achieved since then, including some very interesting blog posts by my colleagues. Several turned to data on the distribution of wealth, including some studies in which I participated, noting the lack of gains—especially in the past few decades—in the wealth and income of blacks and Hispanics relative to whites.

Those aggregate, raw figures on wealth and income act as a form of performance test on one aspect of government policy. They state rather emphatically that, whatever its merits, such policy was not sufficient to move the needle on wealth mobility across and among racial and other classes. Some simply draw the conclusion that we must redouble our efforts on programs that they have favored for a long time. Spend more on Medicare or Medicaid or cut tax rates or whatever. But what if that focus is wrong? What if the dominant liberal and conservative agendas over the past 50 years, at least when it came to social policy and taxes, never really had much to with mobility? What if the data compel us to adopt more dynamic, yet realistic, policies that put mobility and opportunity more at the forefront of policy in the 21st century?

Over these past few decades, liberal agendas have focused largely on the positive effects of ensuring that people had adequate income, food, health care, and so on—that is, consumption. Conservative agendas have focused largely on the negative effects of high income tax rates, particularly at the top of the income distribution. Often raising legitimate concerns about poverty or incentives, respectively, in many ways, each side has won its battle. Redistributive and other social welfare policies now dominate the $55,000 in federal, state and local spending, including tax subsidies, now spent on average per household, while tax rates at the top tend to be about half what they were from World War II to the early 1960s.

Relative to 50 years ago, fewer people are without food or food assistance, people can now retire on Social Security for many more years, health care has become far more life-sustaining, more people go to college, and, while economic growth hasn’t been great lately, we’re still about three times richer than we were. So the record isn’t all that bad, despite current travails. But, once again, those successes largely did not carry over to mobility among and across classes.

Here are just a few examples of how policies have given limited attention to mobility:

- Current welfare policy helps feed and house people, but it often discourages work by imposing very high costs on moderate-income households with children, as they can lose hundreds of dollars of benefits for each $1,000 they earn.

- Even while single parenthood remains a major source of poverty for many, that same welfare policy now penalizes—on the order of hundreds of billions of dollars—low-income couples with children who decide to get or remain married.

- Although investing in quality early childhood education appears to have a high payoff, the means testing of Head Start and other programs re-segregates our schools, with poorer kids often clustered together in classrooms separate from middle-class kids.

- Housing rental subsidies help people live in decent housing, but they also discourage home-buying and paying off a mortgage along the way, keeping lower-income families away from that classic and, for large segments of the population, most important mechanism for saving.

- Our retirement policies help most Americans live their later years in some comfort. But by encouraging early retirement, Social Security and other programs lead to an increased wealth gap among the elderly as richer classes retire later—hence, work and save longer—than poorer classes.

- Low tax rates may encourage entrepreneurship, but when they don’t raise enough revenue to pay our bills, they add to interest costs on the debt, gradually eroding support for investments in people, education, and similar efforts.

It’s not that liberals and conservatives advocating these older agendas don’t care about mobility. They’ll tell you that people with more sustenance will be able to work and study harder and entrepreneurs facing lower tax rates will create more jobs. But they try to claim too much for agendas that, though successful on some fronts, did not improve mobility in recent decades. The proof is in the pudding.

Raising these issues threatens those who fear that acknowledging failure on any front merely empowers those who advocate for the opposing agenda. And in today’s chaos that passes for policymaking, that is probably true. I don’t even know in what galaxy to place debates over previously nonpartisan issues like extending the debt ceiling so Congress can pay off its bills.

For me, it isn’t about abandoning the past. It’s simply about moving on.

How Much Should the Young Pay for Yesterday’s Underfunded Pension Plans?

Posted: August 22, 2013 Filed under: Aging, Columns, Income and Wealth, Taxes and Budget 2 Comments »Recent stories about Chicago’s pension crisis represent only the latest in a long series of announcements about poorly funded state and local pension plans. Detroit’s declaration of bankruptcy shows one possible consequence of such neglect, with many of the city’s retirees fearing drastically reduced pension payments. This isn’t the first time that retirees and workers have found their financial stability threatened, either: many private pension plans have failed in such industries as steel production and airlines.

While there’s often no easy or right answer for who should pay for these uncovered burdens, as a society we’ve pretty much decided that in this arena, as in so many others, the young should get the shaft.

Often poorly funded or badly designed to deal with risk, many pension plans need only some catalytic economic change, whether from greater competition or an economic downturn, to start sinking rapidly. A promise for the future, underfunded from the past, shifts liabilities forward in time, where they get passed around like a hot potato. No one—employer, worker, or taxpayer—wants to get burned with the cost of past mistakes, or even part of it. But the money that should have been set aside has long been spent, so someone at some time must cover the shortfall.

Consider why government or private employers underfund a plan in the first place. In a private plan, underfunding allows higher wages to current workers, bonuses to top managers, and cash withdrawals to partners and dividend recipients. In a public plan, elected officials can give higher current compensation to workers or more services to the population while letting taxpayers off the hook–temporarily, of course.

When people see this inadequately supported edifice begin to crumble, they make a run on the bank. Given the increased threats to future wages, job security, and dividend payments, everyone has an incentive to get what they can while the getting is good. Keep wages up as long as possible, even if that means further weakening pension plans. Increase those bonuses to top managers, who suggest their skills are needed now more than ever to dampen the firm’s or agency’s fall. Lobby Congress and state legislators to allow employers to defer better funding of their pension plans so these other cash outflows can continue. And maintain pension payments for current and near-retirees regardless of the hit on those not yet retired.

Traditional actuarial calculations—the formulas by which actuaries determine whether employers adequately fund their plans—make matters worse. These formulas often allow employers to play Wall Street with their pensions. A firm or government borrows at low interest rates on one side of the ledger, then invests in riskier assets with higher expected returns on the other side. Even dodging the question of when such practices generally make sense, employers often push their actuaries to use outrageous assumptions about rates of return on those risky assets.

For instance, many state and local governments today assume a return of around 8 percent on a mixed portfolio of bonds and stocks in a world where interest-bearing bonds often yield only 3 or 4 percent at best and the earnings-to-price ratio (the effective rate of return earned by corporations relative to the price of their stock) is about 6 percent in real terms. If these employers want to play the markets with their pension plans, then the plans should be overfunded enough to handle the risk. Alternatively, governments and firms should make their projections assuming a less risky but lower rate of return. If the risk-taking strategy works, then future (not current) funding payments can be lowered.

When the firm or government declares bankruptcy, many bondholders, pensioners, and remaining workers deserve sympathy. Certainly the retiree who might have to rely on less than expected, the bondholder who accepted a lower rate of return in exchange for what she thought was a less risky investment, and the taxpayer who often gets caught covering everyone else’s problems. Sometimes these are the same people who benefited from the excessive payments (made possible, first, when inadequate funds were put into the pension plan, and then, during the delay between recognizing the problem and taking some later action such as bankruptcy). But often they are not.

While these claimants may battle each other, they almost always collude against the young. The use of unreasonable actuarial assumptions establishes this pattern by forcing future workers and taxpayers to cover shortfalls. In addition to covering some of those losses, new workers for the state or the firm, if it survives, will be granted far fewer pension or retirement plan benefits than even current workers, not merely those already retired.

Unequal pay for equal work becomes the new standard. Age discrimination against the old is illegal, but not the young. State pension plans now typically provide tiered benefits, with successively lower benefits for newer workers. In fact, states are now starting to provide negative employer benefits to the young by giving them back less in benefits than their contributions plus some modest rate of return.

The same holds in different ways in private industry. We are all familiar with the higher cash and pension benefits being paid to older airline pilots and automobile workers, among others. Almost no one addresses the consequences for wealth-building, including retirement adequacy, for today’s young. That’s tomorrow’s problem.

Or is it? Seems like we’ve heard that claim before.

You Can Limit Our Deductibles, but it Won’t Reduce Our Health Care Bills

Posted: August 15, 2013 Filed under: Columns, Health and Health Policy, Taxes and Budget 2 Comments »When the Obama administration recently delayed its mandate on out-of-pocket health costs, experts and politicians started debating whether this delay affects our longer-term ability to implement Obamacare. I don’t think it does, but I also think we’re missing the bigger point. Once again, the United States is facing the total disconnect between our nation’s health care policies (whether Obamacare, Ryancare, or “your favored politician’s name here”-care) and the simple, unavoidable arithmetic of health care costs.

Let’s examine the latest example. Obamacare includes a mandate on insurers that out-of-pocket health care costs cannot exceed $6,350 for an individual or $12,700 for a family, numbers often cited as “catastrophic.” At first glance, these limits may sound high: six or twelve thousand dollars is a sizeable expense. But consider: households spend an average of $23,000 a year on health care. If it is considered catastrophic to ask some households to pay $12,000 in out-of-pocket expenses, then how can—or, more accurately, how do—all households cover costs that average almost twice as much?

A similar mathematical conundrum is playing out in another part of Obamacare. Congress determined that we shouldn’t have to pay more than 9 or 10 percent of our income for a moderately comprehensive health policy in the new health exchanges. But

consider: health costs now average about one-fifth of personal income and one-third

of money income. So how do we cover the difference?

The simple answer is that if we don’t pay in one way, we pay in another. Mandate any new limit on what consumers have to pay directly—on out-of-pocket deductibles, Medicare co-payment rates, drug costs under the Part D legislation pushed by President George W. Bush, or our share of the cost of health insurance in President Obama’s new health care exchanges—and those expenses don’t simply disappear. They just get tacked on somewhere else.

Of course, I’m only talking about averages. So you might object, “Well, at least I’m not the one who pays.” Perhaps true, but not as much as you might think.

Perhaps you are fairly healthy and have lower health needs. Insurance policies, however, shift costs from the unhealthy to the healthy. That’s as it should be, but the cost of insurance adds to any out-of-pocket cost. Moreover, since unhealthy households tend to have lower incomes to start with, and on average probably can’t cover even average costs of $23,000, healthy households probably pay at least that average amount and probably more to cover the income shortfalls from the less healthy. So being healthy doesn’t let us off the hook.

Perhaps you are middle class or even poor. The government’s health policies redistribute costs from those with higher incomes to those with lower incomes, including the retired. We might think that we avoid paying these high health costs by shifting tax burdens to the rich. Unfortunately, government health costs are already so high that the middle class has to share in the burden of paying for them.

More importantly, even if those health costs could be placed entirely on the rich, the rest of us would still pay what are called opportunity costs. When our elected officials require that a tax be spent on health care, they simultaneously decide that it can’t be spent on education or training or highways or other goods and services. The decline in education spending in recent years while health costs continued to rise provides only the latest piece of evidence.

Regardless of cost shifts to the healthy and those with higher incomes, we still pay a lot ourselves, only indirectly. In particular, we pay through lower cash wages when employers purchase health insurance, an important but often ignored aspect of the slow growth in cash compensation for over three decades. We also pay a decent amount through our own taxes, including federal income and Medicare taxes and all those state excise and sales taxes, often on businesses, that get passed onto us in the form of higher prices on what we buy. Finally, we pay a lot by borrowing from China, Japan, oil-exporting countries, and, more recently, the Federal Reserve, and then passing those outstanding balances and interest payments to our children.

And if paying a lot isn’t bad enough, these methods of paying help insure that we don’t always get our money’s worth. There’s fairly clear evidence that for every $100 of costs pushed into indirect and hidden budgets, our costs rise by more than $100 as health care providers find it easier to raise their prices.

So, the next time someone tells you that we can’t afford health costs that are only a fraction of what we actually pay, ask him where he thinks the extra money comes from.

What Do Mark Mazur, Lois Lerner, and J. Russell George Have in Common?

Posted: July 15, 2013 Filed under: Columns, Nonprofits and Philanthropy, Taxes and Budget 2 Comments »Until recently, few Americans knew the names of these three Treasury officials, long-time public servants whose talent and many years of hard work elevated them to prestigious government positions. But many now recognize, if not their names, the issues with which they have been intimately associated. Each has moved into the spotlight recently after putting out a statement, report, or blog dealing with a very controversial aspect of tax administration: employer mandates under the new health care reform law, or Obamacare, in the first case; and tax exemption for social welfare organizations with such labels as “tea party” or “progressive” in the last two.

What Mazur, Lerner, and George also hold in common is the forced assumption of greater responsibility than is warranted, as elected officials and their top appointees—those who wrote or failed to fix the laws in the first place—scramble to secure a position of innocence and fault-finding in the blame game known as Washington, DC.

Mazur is the Assistant Secretary of the Treasury who first revealed in a blog posting the delayed implementation of one important feature of Obamacare, the mandate on larger employers to pay a penalty if they don’t offer health insurance to their full-time employees. Lerner is the IRS official, now threatened with criminal charges by politicians, who first noted that some of those under her had inappropriately targeted “tea party” and other groups for extra review when they applied for tax exemption as social welfare organizations. George is the Treasury Inspector General whose report on the IRS targeting of tea party groups is now being lambasted by Democrats for failing to note sufficiently that the IRS was simultaneously scrutinizing other applicants, such as progressives.

Should we focus so much attention on the talents of Mark Mazur in regulating, Lois Lerner in enforcing, or J. Russell George in inspecting? (I may be influenced by that fact that I know two of them, but I can assure you that many others would say that each is well above average in integrity, ability, and devotion to the public.) Or should we instead turn our attention to how the government turns inward when it functions poorly, the system creaks, and officials remain at an impasse to fix things everyone has long known are broken?

Every expert on nonprofit tax law will tell you that providing tax exemption for organizations operated for social welfare purposes (“exclusively” under Code section 501(c)(4), but “primarily” under the IRS’s more lenient regulations) does not mesh easily with organizations set up to engage in significant political activity. Also, delays in getting exemption have been an issue for years for nonprofits in general because of lack of IRS staffing, extensive abuse of the law, and the difficult-to-enforce boundary lines between exempt and nonexempt activities, the latter including political campaigning. And if there were an easy way to figure out which organizations really devote themselves to social welfare, why hasn’t the White House or any member of Congress come up with one? If things go amuck in some IRS Cincinnati office, wasn’t error built into the system a long time ago?

As for the health care reform law’s employer mandates, of course these were going to put extraordinary pressures on employers to hire part-time rather than full-time employees, on payroll and other reporting systems to devise ways to measure hours of work (however inaccurately), and on an understaffed IRS to somehow enforce the law’s requirements. If things go amuck, how much responsibility rests with Treasury and IRS versus a political system that can only vote thumbs up or thumbs down on Obamacare?

Rest assured, when new benefits are bestowed on citizens, messages spew forth from elected officials and their spokespersons in the White House and Congress. “Look what we have done for you,” they pronounce. Can you remember top White House and Treasury officials ever deferring preferentially to Mark Mazur to make one of these more politically appealing types of announcements?

When things unravel a bit, however, roles reverse. Elected officials and their top cadre quickly disassociate themselves from both the creation of the problem and their past failure to address it.

Wouldn’t it be a lot more honest to share responsibility for successes and failures, more helpful to reveal rather than hide the limits on tax administration, and more productive to spend more time on fixing than blaming? As long as every difficult issue threatens to become political high theatre, the Mazurs, Lerners, and Georges of long government service will be asked to play the role of clown or villain for scripts they can, at best, edit but not write.

The Baucus-Hatch “Blank Slate” Approach to Tax Reform Could Be Revolutionary

Posted: July 3, 2013 Filed under: Columns, Taxes and Budget 5 Comments »No one quite knows what exactly Senate Finance Committee Chairman Max Baucus (D-MT) and Ranking Member Orrin Hatch (R-UT) mean when they say they will rely upon a “blank slate” as the starting point for tax reform discussions. But done carefully and with political artistry, taking advantage of their unique power, Baucus and Hatch could revolutionize how members of Congress negotiate the future of taxes.

But it’s all in the practice, not the theory. Done right, the strategy could reenergize the tax reform debate. Done wrong, it will be just another dead-end.

The idea of reforming the tax system from a “zero base” or building up from a blank slate is hardly new. And lawmakers always talk about everything being on the table. The challenge is in making it happen.

Baucus and Hatch must accomplish two goals. First, they must shift the burden of proof from those who favor reform to those who would retain the status quo. Second, they must force members to pay for their favored subsidy, denying them the opportunity to pretend it is free.

As a veteran of the Tax Reform Act of 1986, I always emphasize the crucial role of process. Sure, serendipity smiles or frowns unexpectedly on any endeavor, but the ’86 effort took off when Treasury, President Reagan, House Ways & Means Chair Dan Rostenkowski (D-IL), and Finance Committee chair Bob Packwood (R-OR) all put forward proposals that started with specific rate cuts and removal of many tax preferences.

Their plans were all somewhat different, but each changed the burden of proof. Lobbyists won many later battles, but now they were forced to explain why they needed to retain special preferences when others would not be so favored. Moreover, given a fixed revenue target, restored preferences had to be paid for. Lawmakers had to acknowledge that the price of adding back tax preferences was a higher tax rate.

Baucus, ideally with the support of Hatch, can put forward a “chairman’s mark” from which committee members can debate amendments. As both senators have suggested, that mark can be a relatively clean slate. Further, Baucus can require that amendments must not add to the deficit or change his revenue target, effectively requiring members to offer what are called “pay-fors.”

Normally, members debate items one at a time. Each adds a new subsidy without worrying about who pays for it—perhaps those currently too young to vote or the yet-unborn.

In dark times, politicians try to reduce the deficit by figuring out what tax increases or spending cuts will restore order to the budget. But identifying losers is immensely unpopular among voters, and politicians shy away from it. Worse, they blast those from the other party brave enough to provide details.

But if Baucus sets a revenue target at the beginning of this tax reform exercise, the dynamic shifts—from simply identifying winners and losers to explicit trade-offs. Winners and losers march together. With a blank slate or zero base, every restoration of a tax break requires higher rates (even an alternative tax), especially if there are few or no alternative preferences to sacrifice.

This process not only gives new life to a broad rewrite of the tax code but also makes it much easier to reform specific provisions. For instance, tax subsidies for homeownership, charity, and education can be much more effective and provide more bang per buck out of each dollar of federal subsidy. But politicians largely ignore such ideas because they create losers who scream loudly. Thus, the default for elected officials who fear negative advertising and loss of campaign contributions is to do nothing to improve these tax subsidies.

But when the burden of proof changes, a lobbyist can appear to be helping his masters simply by saving a subsidy, even if the net benefit is smaller than in the old law. After all, preserving a preference in some form is success relative to a zero baseline. Of course, as we learned in 1986, this argument grows stronger as the probability of tax reform grows. Can Baucus and Hatch change the burden of proof and force members to pay with higher rates for the subsidies they want to keep? They can certainly lead their committee and Congress in that direction, but only by specifying precisely a chairman’s mark that sets revenue and rates while slashing tax preferences.

If they do, Baucus and Hatch may force fellow senators to acknowledge that every subsidy must be paid for. And that, in turn, will open a window to design alternative tax subsidies that are fairer and more efficient. This sort of process revolution could remake policy in ways that extend well beyond tax reform.

Austerity, Stimulus, and Hidden Agendas

Posted: June 11, 2013 Filed under: Columns, Economic Growth and Productivity, Taxes and Budget 2 Comments »Nothing better exemplifies our gridlock over the future of 21st century government, as well as how to recover from the Great Recession, than the false dichotomy of austerity versus stimulus.

The austerity thesis, reduced to its simplest form, suggests that government has been living beyond its means for some time, only exacerbated by the actions that accompanied the recent economic downturn. Sequesters, tax increases, and spending cuts become the order of the day.

The stimulus hypothesis, reduced also to simplest form, suggests that more government spending and lower taxes puts money in people’s pockets and helps cure a country’s economic doldrums. Once the economy is doing better, government spending will naturally fall and taxes rise.

The debate then plays out largely over deficits: do you want larger or smaller ones?

But reduced to this form, the debate is a fallacy, for several reasons.

First, one must define larger or smaller relative to something. Last year’s spending or taxes or deficits? What’s scheduled automatically in the law? The public debate often glosses over these issues. Which is more expansionary when keeping taxes at the same level: an economy whose growth in spending is cut from 6 to 4 percent or one whose growth is increased from 1 to 3 percent?

Second, a country’s ability to run deficits depends on its level of debt. A recent debate over whether at some point higher debt starts to slow economic growth doesn’t change the fact that lenders want to be repaid. People won’t loan to Greece now, but they still find the U.S. Treasury securities a safe haven for their money.

Third, and by far the most important, what timeframe is involved? Is the Congressional Budget Office pro-austerity or pro-stimulus when it concludes that sequestration hurts the economy in the short run, but is better in the long run than doing nothing about deficits? No one on either side suggests that debt can grow forever faster than the economy. Everyone implicitly or explicitly believes that to accommodate recessions when debt grows faster there are times when debt must grow slower.

So where’s the rub? Here you must understand the emotional systems, usually veiled, that lie behind those on both sides trying to force the problem to an either/or solution.

Start with hardline austerity advocates. Many of them don’t just want smaller deficits. They want smaller government—or, at the very least, they want to prevent the government from taking ever larger shares of the economy, even given changing demographics. Essentially, austerity advocates don’t trust their pro-stimulus adversaries, some of whom can almost always find an economy going into a recession, in a recession, coming out of a recession, or attaining a lower-than-average growth rate and, therefore, needing some form of stimulus. Austerity advocates have learned from long experience that once government spending is increased, it’s hard to reduce. So they feel they have to get what deficit reduction they can now that the public’s attention to recent large debt accumulations is creating pressure to act.

Now for many the hardline stimulus advocates, their support for additional temporary government intervention cannot be entirely disentangled from their sympathy for a larger future government. Else why not agree to cut back now on the scheduled acceleration of entitlement programs, particularly fast-growing health and retirement programs? That would bring the long-run budget, at least as currently scheduled, back toward balance. It would simultaneously please many of their austerity opponents and allow for more current stimulus.

The hidden agendas are complicated further by inconsistencies on both sides. Many hardline austerity advocates, at least in the United States, don’t want cuts to apply to defense spending. For their part, many hardline stimulus advocates would be glad to pare growth in tax subsidies.

Regardless, the dichotomy falls apart once one realizes that a solution can involve a slowdown in scheduled growth rates in spending and a higher rate of growth of taxes, accompanied by less short-run deficit reduction and an abandonment of poorly targeted mechanisms such as sequesters.

Consider the buildup of debt during World War II, the last time we saw U.S. levels above where they are today. Debt-to-GDP fell fairly rapidly after the war all the way until the mid-1970s. While the growing economy certainly helped, tax rates that were raised substantially during the war were largely maintained afterward, and spending had essentially no built-in growth (actually huge declines when the troops came home). Just the opposite holds now even with recovery: there are limited tax increases to pay for past accumulations of debt or wartime spending, and spending is scheduled to grow long-term, even after temporary recession-led spending and defense spending on Afghanistan declines.

Both sides—pro-austerity and pro-stimulus—want desperately to control an unknown future, either by not paying our current bills with adequate taxes or by maintaining built-in growth rates in various programs, mainly in health and retirement. The false dichotomy between austerity versus stimulus has fallen by the wayside, and what we see through the veil are two sides in mutual embrace trying to control our future, whatever the cost to the present.

Growth in Income and Health Care Costs

Posted: June 4, 2013 Filed under: Columns, Economic Growth and Productivity, Health and Health Policy, Income and Wealth, Race, Ethnicity, and Gender 4 Comments »Worried about the stagnation of income among middle-income households? Or about the growth in health care costs? The two are not unrelated. In fact, middle-income families have witnessed far more growth than the change in their cash incomes suggest if we count the better health insurance most receive from employers or government. But is that all good news? Should ever-increasing shares of the income that Americans receive from government in retirement and other transfer payments go directly to hospitals and doctors as opposed to other needs of beneficiaries? Should workers receive ever-smaller shares of compensation in the form of cash?

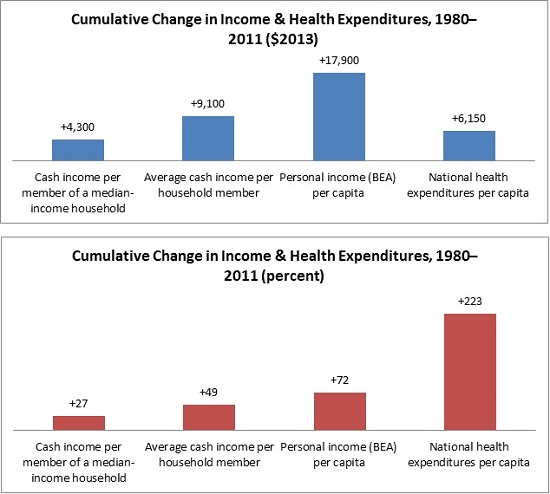

The stagnation of cash incomes in the middle of the income distribution now goes back over three decades. Consider the period from 1980 to 2011. Cash income per member of a median income household, which includes items like wages and interest and cash payments from government like Social Security, only grew by about $4,300 or 27 percent over that period, when adjusted for inflation. From 2000 to 2010, it was even negative. Yet according to data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis, per capita personal income—our most comprehensive measure of individual income—grew 72 percent from 1980 to 2011.

How do we reconcile these statistics? By disentangling the many pieces that go into each measure.

Growing income inequality certainly plays a big part in this story: much of the growth in either cash or total personal income was garnered by those with very high incomes. So the growth in average income, no matter how measured, is substantially higher than the growth for a typical or median person who shared much less than proportionately in those gains. But personal income also includes many items that simply don’t show up in the cash income measures. Among them is the provision of noncash government benefits, such as various forms of food assistance.

Health care plays no small role. In fact, real national health care expenditures per person grew by 223 percent or $6,150 from 1980 to 2011, much more than the growth in median cash income. If we assume that the median-income household member got about the average amount of health care and insurance, then we can see how little their increased cash income tells them or us about their higher standard of living.

Getting a bit more technical, there’s a danger of over-counting and under-counting health care costs here. Some of the median or typical person’s additional cash income went to extra health care expenses, so the additional amount he/she had left for all other purposes was even less than $4,300. However, individuals pay only a small share of their health care expenses; the vast majority is covered by government, employer, or other third-party payments. So, roughly speaking, typical or median individuals still got well more than half of their income growth in the form of health benefits.

The implications stretch well beyond middle-class stagnation. Employers face rising pressures to drop insurance so they can provide higher cash wages. For instance, providing a decent health insurance package to a family can be equivalent roughly to a doubling of employer costs for a worker paid minimum wage. The government, in turn, faces a different squeeze: as it allocates ever-larger shares of its social welfare budget for health care, it grants smaller shares to education, wage subsidies, child tax credits, and most other efforts. Additionally, the more expensive the health care the government provides to those who don’t work, the greater the incentives for them to retire earlier or remain unemployed.

In the end, the health care juggernaut leaves us with good news (that our incomes indeed are growing moderately faster than most headlines would have us believe) as well as bad news (that health care remains unmerciful in what it increasingly takes out of our budget).

Homeownership as a Means of Reducing Wealth Disparities

Posted: May 30, 2013 Filed under: Columns, Economic Growth and Productivity, Income and Wealth, Race, Ethnicity, and Gender 2 Comments »COAUTHORED WITH DOUG WISSOKER

A recent paper by Bayer, Ferreira, and Ross on mortgage delinquencies and foreclosures finds that people of color had greater problems once Recession hit than did many others in roughly equal circumstances, such as income and location, but with different racial backgrounds. We believe this is a useful, though not surprising, finding in ongoing studies of the impact of the Recession on different types of households. Yet we worry about how its results get extrapolated into policy recommendations.

The paper concludes that their research “raises concerns about homeownership as a vehicle for reducing racial wealth disparities”. We believe that one needs to be very careful in extrapolating lessons from the market of the mid-2000s to any market and to policies that would apply over time. Paying off mortgages is the primary means by which the majority of households, particularly low and moderate-income households, save over time. Discouraging such saving could easily add to already unequal distribution of wealth in society.

First, a quick summary of the findings. Combining several sources of data to look at racial differences in delinquent payments and foreclosures for mortgages for purchases and refinances originated between 2004 and 2008, the authors find that black and Hispanic borrowers had substantially higher delinquency and foreclosure rates than whites and Asians, even controlling for differences in circumstances such as the borrower’s credit score, the size of the interest rate spread of the loan, and the identity of the lender. In addition, the authors conclude that the racial gap in delinquent payments and foreclosures peaked for loans originating in 2006. From this, they conclude that people of color entering the market at the peak of the housing boom were particularly vulnerable to adverse economic conditions.

The authors attribute the racial difference found for blacks and Hispanics, even after trying to control for income or other differences, to items they couldn’t measure, including lower wealth and an accompanying lack of a financial cushion. This seems crucial to us and is also consistent with studies that income an incomplete predictor of upward or downward mobility. Work from the Urban Institute (here) shows that wealth differentials by race are much greater than income differentials. These differentials can play out in multiple ways across generations. For instance, wealthier families provide more inheritances and intergenerational transfers that support homebuying and downpayment levels that reduce foreclosure risk.

However, the authors’ concern about homeownership as a vehicle for reducing racial wealth disparities does not follow logically. Evidence here is at best circumstantial. Among other sources of disparate outcomes, consumer groups would point out that these types of findings more than anything highlight the disparate impact of abusive lending at the height of the housing boom.

Portfolio theory requires looking across different types of assets and debts, along with their associated expected returns and risks. Homeownership has risks, but so does renting. In fact, rental rates at times rise faster than the costs of homeownership, and in many parts of the country it has become cheaper to own than rent for those likely to be in a home long enough that transactions costs do not eat away at the ownership returns. Similarly, a household often must choose among debt instruments. Mortgages tend to have lower interest charges than most other forms of debt.

Most vehicles for getting a decent return on investment involve some risk. Saving accounts now paying negative, after-inflation, returns only prove the point in spades. If saving were proportionate to income, for instance, but lower-income individuals invest only in low or negative return assets, then wealth inequality necessarily would grow to be much greater than implied by levels of saving, potentially compounding adverse outcomes over time. Conversely, without discounting lessons from the Great Recession, low-cost, well-structured mortgages continue to be supported by the government (whether through FHA or the GSEs) partly for the very purpose of diversifying risk and effectively spreading wealth ownership.

This study is based on patterns of delinquency and foreclosure rates observed during a limited time period with unusually high foreclosure rates. But, wealth accumulation occurs over a very long time. Thus, even on this paper’s own terms, it’s not clear that reduced rates of homeownership would make low-income households or people of color better off over extended periods. We have found that most homeowners buying a decade or so before the Great Recession came through the longer period in good shape. Our own work also tends to show that black homeownership rates, even after controlling for income, are disproportionately low in both good and bad markets, raising serious questions about whether they are missing out on opportunities available to others.

Regardless of the effect on the difference in wealth disparity by race, homeownership is an effective way for many, though certainly not all, low- and moderate-income households to save. Equity in a home is the primary asset owned by low- and middle-income households, including blacks and Hispanics, by the time of retirement. Paying off a mortgage is the primary mechanism by which these households save, with all the virtues of a more automatic and regular saving vehicle. Reductions in the already low homeownership of people of color would almost certainly exacerbate over time the unequal distribution of wealth.