Why Current Revenue Proposals are Inadequate Compared to the Deficit

Posted: December 5, 2012 Filed under: Shorts, Taxes and Budget 3 Comments »Despite the ideological hype over revenue increases for the upper-income taxpayers and restricting itemized tax deductions, almost all the considered changes will tackle only a portion of the deficit.

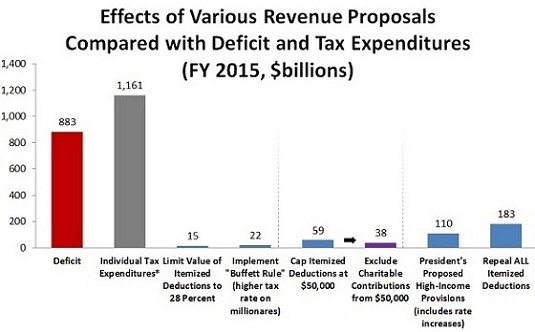

As the graph below indicates, the Congressional Budget Office projects a fiscal year 2015 deficit under current policy of $883 billion, not far from the $1 trillion–plus deficits in the Great Recession and its early aftermath. By comparison, the Tax Policy Center calculates that revenue gained from repealing ALL itemized deductions would be only $183 billion. Smaller limitations on itemized deductions have smaller effects: President Obama’s proposal to limit the value of itemized deductions to 28 percent would raise only $15 billion. Capping itemized deductions at $50,000 would raise $59 billion, or $38 billion if the charitable deduction was excluded.

The value of all individual tax expenditures is $1.161 trillion, even larger than the deficit. But most revenue proposals—particularly those confined to a tiny portion of taxpayers and only a subset of various tax programs—also only chip away at that amount.

Sources: CBO Budget and Economic Outlook, U.S. Treasury Green Book, and Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center.

* Tax expenditures estimate excludes payroll tax effects.

Notes: Baseline is current policy, which assumes extension of 2001 and 2003 tax cuts, except for Individual Income Tax expenditures, which uses Treasury’s baseline.

Several proposals are circulating concerning the Buffett Rule, aimed to insure a 30 percent minimum effective tax on those making $1 million or more a year. The proposal scored by the Tax Policy Center would eliminate the AMT and replace it with a “fair share tax” styled on the Buffett rule. The “fair share” part would raise $22 billion in 2015 (the amount shown in the graph above), but repealing the AMT would lose $54 billion.

Cutting Back on Charitable Incentives: The Case for Automobiles

Posted: November 30, 2012 Filed under: Nonprofits and Philanthropy, Shorts, Taxes and Budget 2 Comments »With Congress and the President seriously considering proposals to reduce various tax subsidies, the charitable deduction has come into play. As opposed to proposals that cut back on giving across the board, it may be worthwhile to consider other alternatives. This short note indicate some evidence on what happened when Congress recently cut back on allowances for donations of automobiles because of perceived abuses.

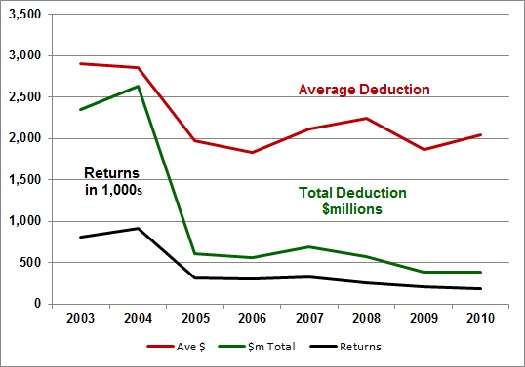

In 2003, a GAO study found suspiciously large unsubstantiated deductions for donations of vehicles to charity. In response to evidence that donors were claiming well in excess of the value of these deductions to charities, Congress in 2004 limited the deduction for vehicles worth over $500 to the charity’s actual selling price of the vehicles. It also required donors to attach a statement of sale indicating that it was “sold in an arm’s length transaction between unrelated parties” or a written statement that the charity would use the donated car in its programs. Higher deduction amounts were still allowed for charities that used the vehicles directly, as opposed to selling them.

The graph below shows that tax deductions claimed for vehicles fell sharply after enactment of this law.

Source: Gerald Auten, Department of Treasury.

For more information on noncash contributions generally, see “Noncash Charitable Contributions: Issues of Enforcement” which includes postings on noncash charitable contributions, an area worth $44 billion to nonprofit organizations in 2010.

How Earnings Affect Benefits for Households with Children: The Extreme Welfare Case

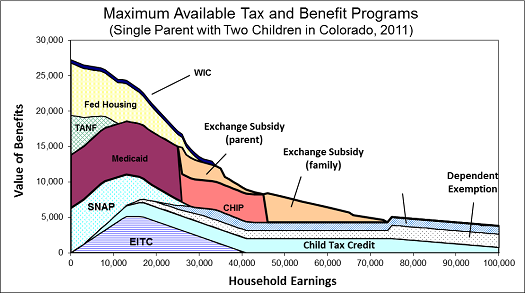

Posted: November 1, 2012 Filed under: Children, Income and Wealth, Shorts, Taxes and Budget 4 Comments »In theory, a household may be eligible for a broad range of government supports. Some are universally available, such as earned income tax credits and SNAP (formerly called food stamps) to a household with children if earnings are low enough. (See a previous short on this subject.) Others are only available to some people. For instance, government establishes waiting lists for programs like rental housing subsidies and limits number of years of participation in the traditional welfare program, now called Temporary Assistance to Needy Families or TANF.

The figure below assumes a single parent with two children is receiving almost all these benefits, an extreme case. It includes the more universally available programs, like SNAP. It also assumes the availability of the new Exchange subsidy provided by health reform. Benefits add up to close to $27,000 when this household fails to work and fall to about $8,000 as earnings increase to $40,000. Note that the graph does not take into account free child care support or income and Social Security taxes. When these are added to other benefit reductions, the household can sometimes even lose net income by earning more.

For further detail see my testimony before the House Subcommittees on Human Resources and Select Revenue Measures on June 27, 2012, “Marginal Tax Rates, Work, and the Nation’s Real Tax System.”

How Earnings Affect Benefits for Households with Children: The More Universal Case

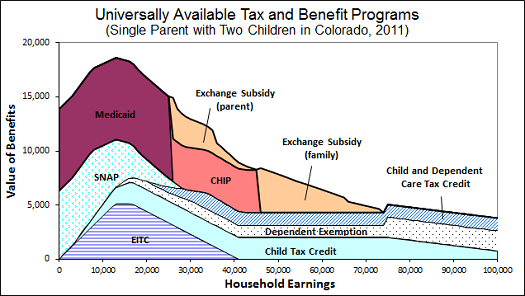

Posted: October 31, 2012 Filed under: Children, Income and Wealth, Shorts, Taxes and Budget 5 Comments »Many government programs automatically grant eligibility to all families with children, depending only on their income. As their incomes increase, however, these families often, but not always, receive fewer benefits. Some restrictions operate on a schedule: earn $1 more, get 30 cents less in benefits. Medicaid provides eligibility up to a given income level, then denies eligibility when one more dollar is earned (though usually with a delay). The dependent exemption only is available to those owing taxes, and only at high income levels is removed by the alternative minimum tax.

How do these programs interact?

The figure below considers a single parent household with children and shows how these various benefits vary as the earnings of the household increase. Because every household with children, including you and me if we are raising children, is eligible for these programs if our income falls in the right ranges, we can be said to belong to this benefit and benefit reduction system. For instance, as income increases from $10,000 to $40,000, our household would lose most earned income tax credits, SNAP (formerly known as food stamps), and much Medicaid, though under health reform other health subsidies would still be available. Note that in addition to these losses of benefits, direct tax rates from income and Social Security taxes would apply, though they are not shown here. For further detail see my testimony before the House Subcommittees on Human Resources and Select Revenue Measures on June 27, 2012, “Marginal Tax Rates, Work, and the Nation’s Real Tax System.” My next short describes the extreme welfare case.

An Extremely Mucked Up Medicare Debate

Posted: October 29, 2012 Filed under: Columns, Health and Health Policy, Taxes and Budget 6 Comments »Or

Democrats and Republicans Favor Medicare Cuts and Then Deny It

Medicare is taking on a primary role in the presidential race. The discussion often turns to whether the program should continue in its current form, with more direct government controls over costs, or shift its emphasis to vouchers or premium support plans. Let’s try to set the record straight.

Lowering Medicare spending growth over the next 10 years from, say, an additional $500 billion to an additional $400 billion means spending $100 billion less on covered services. It doesn’t matter for budget purposes the source of the saving. It is a benefit reduction.

Both presidential candidates claim to save money on Medicare without cutting benefits. President Obama says his reforms “will save Medicare money by getting rid of wasteful spending…that won’t touch your guaranteed Medicare benefits. Not by a single dime.” Meanwhile, Governor Romney promises that his “premium support” plan will save money while still providing “coverage and service at least as good as what today’s seniors receive.”

But politicians aren’t the only ones dispensing that free-lunch rhetoric. Even highly respected journalists and researchers get pulled into it.

Consider two New York Times stories. After the first presidential debate, Michael Cooper, Jackie Calmes, Annie Lowrey, Robert Pear and John M. Broder said that President Obama “DID NOT CUT BENEFITS by $716 billion over 10 years as part of his 2010 health care law; rather, he reduced Medicare reimbursements to health care providers.” A few days later, David Brooks cited an AMA study of a premium support plan put forward by vice presidential candidate Paul Ryan and Democratic Senator Ron Wyden, saying that “costs might have come down by around 9 percent with NO REDUCTION IN BENEFITS” [cap emphases mine].

Can you see what is going on? Politicians, reporters, and experts all recognize that cost growth must be brought under control. But they also want to suggest that benefits won’t be reduced—if only we go with a particular approach.

It’s one thing to say that we can spend $100 billion less on health care so we can use the money better for education or tax cuts or paying off our debt. But it’s another thing to pretend that we can get $100 billion more in educational benefits or money in our pockets and absolutely the same quality of health care.

We know from personal experience that certain medical procedures, at the end of the day, are worthless or worse. But there’s no budget line called “worthless health care” that our elected officials can bravely vote to reduce.

Instead, we are left with blunt instruments to control costs. A Medicare board may recommend or members of Congress may elect to cut payments to providers, as they have done many times in the past. One can argue such cutting may not produce a great loss in services, depending upon how providers and consumers react. But no loss whatsoever? Come on! Try lowering government payments for anything—rental vouchers, school lunches, highways—and see if the same services are provided.

Similarly, suppose that Congress puts more Medicare recipients into a premium support system, like Medicare Advantage–type plans run by health maintenance and similar organizations. The system then limits the growth rate of payments to those groups. Again, there’s less money to go around.

Both the regulatory and voucher approaches have a precise accounting correspondence. If the government spends $100 billion less, then it purchases $100 billion less in services and makes $100 billion fewer payments to providers.

Back to the presidential and vice presidential debates. Directly trying to control prices for individual services may not have the same effect as trying to control the total amount paid for all services under a premium, and vice versa. But no candidate can deny that he favors benefit cuts relative to today’s unsustainable promises.

To add to the confusion, each side talks as if some idealized system of cost control or premium support exists. Almost inevitably, we will be taking ideas from both approaches. We’ll cut back on high reimbursement rates when we believe the effect on actual services would be moderate and, at the same time, use limited budgets to encourage providers to operate more efficiently. For instance, we might lower the payment rates for many operations faster and simultaneously induce more Medicare recipients to opt into groups like Kaiser-Permanente that make many allocation decisions within a fixed budget.

Ferreting out the truth in this Medicare debate also requires looking beyond health care. Benefit losses in health care must be contrasted with benefit gains elsewhere. Yet even health care will likely be much worse if we continue to borrow hundreds of billions of dollars more from unfriendly nations and let excessive debt inhibit economic growth.

Bottom line: both parties favor cutting Medicare benefits, or, more accurately, slowing down the rate of benefit growth. The issue isn’t whether but how this can best be done.

Charities Making Payments in Lieu of Property Taxes

Posted: October 26, 2012 Filed under: Nonprofits and Philanthropy, Shorts, Taxes and Budget 11 Comments »Urban Institute recently held a conference on “State and Local Budget Pressures: The Charitable Property-Tax Exemption and PILOTs” which explored how increasing fiscal pressure on governments on the state and local level has led governments to re-examine which charities should be exempt from property taxes, and in some cases to ask for Payments in Lieu of Taxes (PILOTs), a voluntary payment of portion of their exempt property taxes from nonprofits.

The first panel “The Current Landscape” looked at costs and benefits of the current exemption; the second “Focus on Eds and Meds” took a closer look at the largest and most controversial beneficiaries of the exemption, nonprofit hospitals and colleges and universities; and the third “Negotiated Payments in Lieu of Taxes as Wave of the Future?” debated the use of Payments in Lieu of Taxes (PILOTs) and discussed how a well-designed PILOT program could be created.

The graph below, from a presentation by Daphne Kenyon of the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, highlights the increasing prevalence of PILOTs as local governments seek new sources of revenue.

States with Jurisdictions Collecting PILOTs

Daphne Kenyon. 2012. “Payments in Lieu of Taxes: Balancing Municipal and Nonprofit Interests.” Urban Institute conference on “State and Local Budget Pressures: The Charitable Property-Tax Exemption and PILOTs,” on May 21, 2012 at the Urban Institute.

For more details I recommend reading the brief based off the conference, which describes the mechanics of governments asking for voluntary taxes from nonprofits in more detail, and gives an overview of the debate over such payments.

Governing After Over-Promising

Posted: October 18, 2012 Filed under: Aging, Columns, Health and Health Policy, Taxes and Budget 4 Comments »For almost anyone following closely our presidential candidates’ statements, it is absolutely clear that each pledges more than he can deliver. As a result, we must vote for the candidate who can better govern after over-promising.

Consider especially the big three items driving upward the budget deficits: growth in health costs, growth in retirement costs, and the tax cuts that keep passing our bills and related interest costs onto future generations. One simply can’t balance the long-term budget without dealing with these three. Yet both Obama and Romney remain largely silent about what we might have to give up in these arenas for years to come.

Social Security reform? “We can easily tweak the Social Security program while protecting current beneficiaries, ensuring that it’s there for future generations,” President Obama says. “[I am not] proposing any changes for any current retirees or near retirees, either to Social Security or Medicare,” Governor Romney proclaimed at the first presidential debate.

Medicare? The president fights to retain long-run hopes for “well over $1 trillion” in cost savings that he thinks are in Obamacare. But the Congressional Budget Office says that Obamacare raises health costs overall and that any long-run savings are just that, long-run, as well as uncertain. Romney would replace Obamacare and restore additional Medicare-directed spending. CBO numbers say that simply abandoning Obamacare would add to the deficit since the bill also includes tax increases and other measures that more than offset the health cost increases.

As for premium support or vouchers versus traditional Medicare, the candidates do engage in a debate, but generally over changes that would be phased in at some time long distant from when they need to tackle the deficit. Taxes? Romney proclaims that his reform would reduce revenues or at best be revenue neutral: “We are not going to have high-income people pay less of the tax burden than they pay today. […] I do want to bring taxes down for middle-income people.” He would also cut tax rates by 20 percent and “keep revenue up by limiting deductions and exemptions,” or perhaps he would do less, if those limits don’t supply enough revenues. Obama, in turn, holds with his promise from the last campaign for no tax increases for anyone making less than $250,000. Analysis after analysis shows that keeping this promise would entail only modest progress on the deficit.

Discretionary spending? Although not one of the big three drivers of our budgetary problems, both candidates would pare it dramatically as a share of GDP, but their campaigns only emphasize what they would protect. Obama would invest in education, and Romney now likes Pell grants, though he would give Big Bird some liposuction. Romney says he would somehow maintain a higher defense budget than Obama.

These candidates are not the first to try to tell us how much they will do for us or at least how they will absolve us—particularly the woe begotten middle class—from sharing in any future budgetary fix. Their complication, even compared with previous presidential elections, is that their new promises stack onto an extraordinary and unprecedented number of unsustainable promises already put into law. I understand why they are scared to death to tell us what reforms might really be required; we voters often jump on the honest candidate and, hence, bear some responsibility for what we get. But that means that in deciding for whom to vote, we must speculate on just which pledges either candidate would violate.

Should we prefer the candidate more willing to declare “oops” once elected?

Do we vote for the one whose future contradictions we believe will be less likely to affect our favorite interests?

Do we favor the politician more adept at dissimulating his past statements?

Consider many of the recent budget agreements and systemic reforms that required us to give up something. Reagan abandoned his opposition to removing tax breaks both in the budget agreements and the major tax reform legislation he signed. He also reversed his previously successful efforts to provide zero and often negative tax rates on some investments. Clinton abandoned his pledge for a tax cut soon after being elected. George H.W. Bush famously abandoned his “no new taxes” pledge. And while poor H.W.’s dissimulation efforts were unsuccessful, conservative and liberal pundits still place Reagan and Clinton high in their respective pantheons.

The president is the only elected official who represents all the American people. The office demands a higher order of integrity and just plain arithmetic discipline than does the role of candidate. In the end, therefore, we probably pick whomever we think better recognizes that the switch from candidate to president is more of a leap than a transition.

The 1 Percent (Political) Solution

Posted: September 13, 2012 Filed under: Columns, Income and Wealth, Taxes and Budget 3 Comments »Political campaigns, particularly modern ones, tend to revolve around promises. That’s as true of Republicans offering tax cuts as Democrats promising to maintain or increase spending programs. When you see candidates from both parties visiting regions hit by hurricanes or drought, you can be sure they are trying to indicate how much they care for those affected. When politicians do venture onto the other side of the balance sheet — how they will pay for all past and current promises — they move much more gingerly.

A candidate for office effectively divides the population into the “deserving,” who should get more benefits or tax cuts (or at least should not pay more taxes or lose benefits), and the “undeserving,” who are not carrying their own weight. But he or she doesn’t want to put very many people in the latter category, since their votes likely will be lost.

That’s where the 1 percent solution comes in.

For Democrats, the 1 percent is the wealthy. President Obama stakes a lot of his campaign on going after those with incomes over $250,000. Many Congressional Democrats often won’t go that far; they confine their attacks and suggested tax increases to those making over $1 million.

For Governor Romney, the latest 1 percent is welfare recipients. Because the Obama administration recently granted waivers from work requirements to some states, more adults can now get benefits without even trying to work, the Romney campaign claims.

OK, “1 percent” is approximate. For you fact checkers, Tax Policy Center calculations indicate that the number of households facing tax increases under the president’s $250,000 threshold (slightly less for single people) is less than 1½ percent of tax units, and the number making more than $1 million (there’s really no specific tax plan to estimate against) is probably only about ⅓ of 1 percent.

Meanwhile, adult recipients of Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, the program most identified with welfare, make up less than 1 percent of all adults in the country; household recipients make up slightly over 1½ percent of all households, though only a fraction of those at best would be affected by any state waivers.

The point here is that depending upon how you count, each party is still trying to pander to between 98½ and 99⅔ percent of us, leaving most of us out of the cost side of the equation. Unfortunately for the country, the nation’s fiscal challenges confront us all!

Perhaps some of us count ourselves as moderates because we would be so bold as to tackle our budget situation by going after both the rich and the welfare recipients. We might find sympathy with the Occupy Wall Street and Tea Party crowds at the same time.

There’s one tiny complication. Almost everyone receives significant benefits from government, and most pay significant taxes relative to their income, although how they do so (income, social insurance, state, local, fees) varies by the individual. At the end of the day, the middle 98 or 99 percent gets most government benefits and pays most government taxes.

So when the federal government collects only 60 cents for every dollar it spends, it is relatively easy for almost everyone to agree that that situation is both economically untenable and arithmetically unsustainable. It is much harder for us to admit that the problem cannot be solved by targeting the 1 percent on either end of the income scale and that we, too, have to chip in.

During a campaign, I don’t want or expect politicians to identify whose taxes would be increased or benefits cut. Such actions would be political suicide and unrealistic, to say the least. Broad-based reform requires more thoughtful analysis than is possible in an electoral process dominated by sound bites and tweets.

Campaigns and politicians, however, should at least identify the types of structures they would construct. God forbid that their media consultants tell them how to specify, piecemeal, the plumbing, engineering and architecture of governance involved. I simply want those running for office to admit that government taxes and spending programs fundamentally have to be restructured in ways that are likely to ask something from all of us, not just 1 or 2 percent.

Like many voters, I’m also tired of being pandered to. I know that political advisers and media consultants like to tell the candidates that they must make their supporters feel superior to the “undeserving” who cause all our problems. Maybe such advice is savvy when it comes to obtaining power or winning each party’s nomination. Given how sticky the polls have remained for both candidates in this race, however, I rather doubt its effectiveness in a general election.

And to what ultimate purpose? Elected officials find it hard to govern these days because, in fact, they have just been elected by treating most of us voters as if we are both selfish and stupid.

More and more Americans have tired of that message. We desperately seek and need leaders who will provide a road map for a mutual journey forward, one that makes progress because we, not just 1 percent of others, share in the load.

This column was originally published by the GailFosler Group LLC and is reposted with permission.