Fiscal Policy After ATRA

Posted: February 1, 2013 Filed under: Shorts, Taxes and Budget 5 Comments »The fiscal cliff–averting American Taxpayer Relief Act (ATRA) significantly changed the policy landscape for what looks to be an extended budget debate over the year. For one, most (though not all) policy uncertainty over expiring tax cuts and credits was settled for the foreseeable future. Congress is very unlikely to pick up any new revenue measures this year.

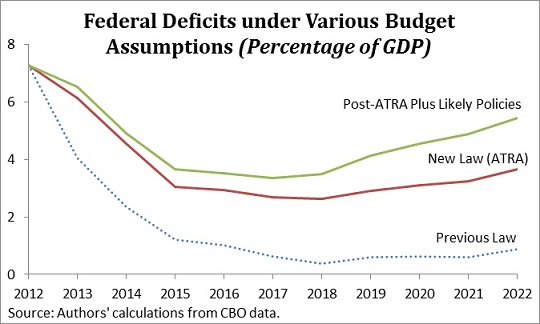

But the bill also highlights how far we are from meaningful deficit reduction. My colleagues and I at the Tax Policy Center have examined what happens to both spending and revenue paths, under the new law and under a scenario that incorporates other likely policies, including the permanent extension of current payment rates to Medicare physicians and a failure to abide by the spending sequester (which, you’ll recall, was a result of the super committee’s failure to reach a budget agreement in late 2011).

We also make an important assumption about the direction of discretionary spending in the long run. Under current law, discretionary spending, on both the defense and domestic sides of the budget, is scheduled to drop to historic lows. Under our “plus likely policies” scenario, we assume that discretionary spending doesn’t fall below its historical lows of 3 percent of GDP for defense and 3.2 percent of GDP for domestic spending. Those lows occurred in 1999 following a period of relative peace, rapid economic expansion, and few of the demographic pressures we now face.

Ben Harris over at TaxVox has more.

What the Public Doesn’t Understand About Social Security and Medicare

Posted: January 30, 2013 Filed under: Aging, Health and Health Policy, Income and Wealth, Shorts, Taxes and Budget 6 Comments »An earlier short highlighted my research with Caleb Quakenbush into how much people pay in Social Security and Medicare taxes over a lifetime, and how much they receive in benefits. For instance, we found that a two-earner couple making an average wage who turned 65 in 2010 would have paid $722,000 in Social Security and Medicare taxes over their lifetimes, but would receive $966,000 in benefits.

These types of numbers often generate outraged debate over how much seniors are “owed” based on what they “paid in” to Social Security and Medicare.

But there is another, more philosophical, issue that these numbers cannot address. Americans do not pay their taxes into a personal account that they can take out, plus interest, when they retire. The money paid into Social Security and Medicare has always been chiefly paid out immediately to older generations. The only exception has been some trust funds which have always been modest in size and are shrinking. Thus, Social Security is effectively a transfer system from young to old, and always has been.

We may feel that because we transferred money to our parents, our kids, in turn, owe us. But we must take into account also how much they can or should afford for this task as opposed to their own current needs for themselves and their children. Think of a one-family society, where three kids support their parents, but then those three kids have no children of their own (or only one or two children). What those three kids gave their parents informs us only slightly on what they can or should get from their own children if there are none or fewer of them. Likewise, when demographics change and there are fewer workers to support an aging population, society has to make adjustments, regardless of what some may otherwise think is “fair” or what they think is their entitlement.

For articles inspired by this research, see a recent PolitiFact.

Our Imperfect Work

Posted: January 22, 2013 Filed under: Columns, Taxes and Budget 13 Comments »“We must act, knowing that our work will be imperfect,” Barack Obama proclaimed in his second inaugural address. Interestingly, the Washington Post blazoned its front page with the first three words without noting the succeeding dependent clause. Yet within this clause, I believe, lies the means by which the president—and Congress—and we—can move past so many of our conflicts and face up to the problems that confront us. The solution lies not in acting, but in recognizing the imperfection of what we do. If our budgets are to be vehicles for change, then we cannot enact so many laws as if the priorities of one time and place must endure forever.

More than ever before, our recent fights carry with them the implication that victory must be complete and total, setting in stone the institutions that will rule over our successors for decades and centuries to come. “We must act,” each political party seems to say, “as if our work will be perfect, else our opponents may someday slow down or even reverse our course.” Permanent monuments must be made to some liberal or conservative agenda, regardless of whether that monument rests upon unstable ground, employs an architecture glued together from incongruous designs, or fails to leave room for the improvements that only future knowledge may reveal.

Today, if we favor Social Security, it must be maintained permanently in its ancient design. For all generations of ever-expanding life expectancies, we must allow beneficiaries to retire as early as 65, or, when feeling temporarily richer, at 62. We must even accept its 1940s stereotype of the two-parent family, with abandoned mothers required to pay taxes to support spousal benefits for which they are ineligible. Similarly, if we favor less government, we can’t just work toward that goal by reducing spending. No, we have to create permanent tax cuts even if that means running economically disastrous deficits.

If we favor helping the poor, then we can never give up support for benefits like SNAP or food stamps. These programs must be etched in the law as superior to any alternative use of those funds, including ones that might provide better opportunities to people in need. If we subsidize an industry, whether oil or alternative fuel or agriculture or manufacturing, then we must enshrine that subsidy in the tax code.

Now, of course, there’s good reason for using legislation to try to provide some certainty or security. With perfect foreknowledge, we can plan for the future. But what if that future remains uncertain? Planning for it then requires creating a way to respond to its surprises, good and bad.

Unfortunately, we’ve gone long past the point where our federal budget could be flexible. A fiscal democracy index I developed with Tim Roeper shows that the combination of entitlement growth and low revenues means that today most revenues are already committed to permanent spending programs. Almost every congressional decision to adjust national priorities has to be paid for out of a deficit, or by overturning some past “permanent” enactment.

Earlier, before entitlements became so prevalent and dominant, spending was largely discretionary. Congress also felt that we should pay our bills on time, so it didn’t finance tax cuts for today’s generations by passing those liabilities onto future generations. Though many programs survived for decades, most still had to receive new votes of support. Even more important, almost none had any built-in growth. That made it easy to let some ideas languish as others came into prominence, leaving room for new choices or reconsideration over time.

Compromise is much easier when one side or the other isn’t forced into reneging on past promises to the public. It’s easier when it’s possible down the road to proceed on the same course, pursue the same objective via a different course, or decide on both a new objective and course. It’s easier when we’re not asking our opponents to keep funding some permanent monument we want erected to ourselves.

“But we have always understood that when times change, so must we; that fidelity to our founding principles requires new responses to new challenges…We understand that outworn programs are inadequate to the needs of our time…Let us answer the call of history, and carry into an uncertain future that precious light of freedom.” (Barack Obama, January 21, 2013; emphasis mine).

Retired Couples Receiving More Years of Support under Social Security

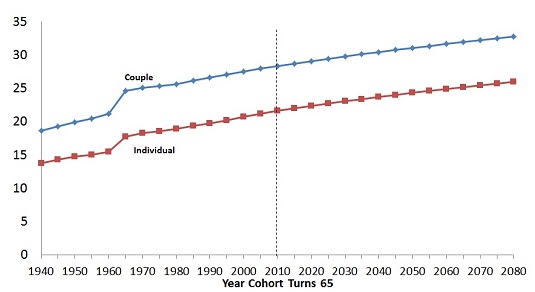

Posted: January 18, 2013 Filed under: Aging, Income and Wealth, Shorts, Taxes and Budget 3 Comments »Increased time spent in retirement is a driving factor behind rising Social Security and Medicare costs. A couple that stopped working at the earliest Social Security retirement age in 1940 would expect to receive 19 years of retirement benefits; a similar couple in 2010 would expect 28 years of benefits. By 2080, couples could be receiving retirement support for 33 years.

This calculation assumes both partners are the same age and will have average life spans. Partners of different ages and those (often higher-income) couples who expect to live longer, such as nonsmokers, receive even more years of support.

As it turns out, these many years in retirement affect more than Social Security balances. Retiring longer also reduces the share of Social Security benefits spent on recipients in their last (e.g., ten) years of life and the income tax revenues to support other government functions.

Expected Years of Retirement Benefits, Earliest Year of Retirement

C. E. Steuerle and S. Rennane, Urban Institute 2010. Calculations based on mortality data from the 2010 OASDI Trustees’ Report.

Assumption: in a couple, at least one partner is still living. ERA was set at 62 for women in 1956 and men in 1961.

For more on this topic, see Correcting Labor Supply Projections for Older Workers Could Help Social Security and Economic Reform.

The Decline of Fiscal Democracy in America: A New Video Series by Eugene Steuerle

Posted: January 7, 2013 Filed under: Columns, Taxes and Budget 3 Comments »On January 3, 2013, the 113th session of the U.S. Congress opened with a fiscal cliff averted, but a country still stuck in a less-recognized fiscal bind.

In the first video of a three-part series, I explore one of the major reasons recent Congresses have been so dysfunctional: all, or almost all, the revenue to be collected by the Treasury Department was spent before lawmakers walked in the door.

I further discuss how spending and tax subsidy programs on autopilot, along with a tax system inadequate to pay our bills and rife with gaping holes, handicap lawmakers’ and the public’s ability to set new goals for solving today’s and tomorrow’s problems.

The Case for Optimism in the New Year: Still Standing on the Shoulders of our Forebears

Posted: January 3, 2013 Filed under: Columns, Economic Growth and Productivity, Taxes and Budget 2 Comments »With all the silliness going on in Washington these days, and with recovery from recession slow here and halting in many other developed nations, we could easily adopt a pessimistic attitude that obscures the prospects lying right at our feet. At the beginning of a new year, I think we instead need to pause and reflect on our graces and blessings, even as we confront the obstacles we have placed in the way of realizing our potential.

First, let’s not translate politicians’ largely self-imposed requirement to make some tough economic choices into the false premise that we lack resources to do anything new, much less better. Are we poor? Hardly. We’re richer than almost any country anywhere and anytime. If we’re growing more slowly than we expect, that only means we’re getting richer more moderately. With average gross domestic product per household now exceeding $125,000, we can easily get misled by focusing on gloomy statistics that exclude or don’t count for improvements.

Here are some among the many pieces of evidence that we often ignore: the ever-better health care that we receive annually through almost any insurance plan, whether employer- or government-provided; the steady increase in life expectancy; and the improvement in the quality of our computers, telecommunications, automobiles, and other durable goods.

Is the public sector in decline? Well, it might be dysfunctional, and it might not be growing as fast as it did in recent decades, but consider: federal and state government spending, including tax subsidies, exceeds $50,000 per household. That amount is greater than the average real income of households from all sources, public and private, in the early 1960s. Transfer programs are more than 50 percent larger than when Ronald Reagan became president. Look closely at every proposed budget, Democratic or Republican, and you will see that they project incomes will increase by about 30 percent—or $5 trillion in today’s dollars—in about a decade. Meanwhile, government spending and revenues will grow by a similar share, perhaps a bit less under one political party than the other. (I hesitate to say that it will grow more slowly under Republicans, since history often belies that conventional wisdom.)

Compare what is required to get the budget in order with what economic growth normally makes possible. Want to reduce budget deficits by, say, 5 percentage points of GDP or about $1 trillion annually in another decade? That’s just a fraction of the rise in incomes that we expect and hope to achieve, yet it’s far more than either political party has come close to suggesting, and probably more than necessary. To top it off, deficit reduction does not mean reduced wealth any more than paying off a credit card does. It merely means that we accept paying more of our bills now rather than passing the liabilities onto our children.

Why the optimism surrounding economic growth? We stand on the shoulders of those who have gone before us. They passed onto us all their knowledge and left us with a country rich in citizens and communities, institutions and inventions, rights and resources. We have a long-established history of entrepreneurial ingenuity; a flexible labor force; the world’s most thriving set of charities, associations, and universities; and, for all our petty bickering, a people united by belief in our republic, and not, as in so many countries, divided by clan or tribe or religion. Even our barriers of race and gender have been falling away, much to the benefit of everyone, not just those who suffer from discrimination.

Not that countries can’t go into decline. Argentina early in the 20th century, Bosnia more recently, and Yemen today provide warnings. The overpromised political systems of Japan, Western Europe, and the United States provide new threats, as does population and labor force decline in some countries. The young are falling behind previous generations in their accumulation of wealth, many people of color have stopped catching up as they did in the past, and our educational systems are showing few gains. Too unequal a distribution of income and wealth also threatens growth for both social and economic reasons (on which I will elaborate little here other than to note how much modern growth everywhere has been correlated with a thriving middle class).

Yes, all these problems threaten us at a time when our political institutions appear to have languished and gone into decline. Yet, even that problem, I believe, reflects a search for a fundamental government transformation that has occurred only a few times in our vibrant, yet still young and ever-challenging, democratic experiment.

At the beginning of another year, therefore, let’s resolve to recognize within our challenges the extraordinary opportunities we, too, possess for bequeathing a better world to our children.

Why Do We Keep Jumping Over the Fiscal Cliff with Bungee Cords?

Posted: December 21, 2012 Filed under: Columns, Taxes and Budget 4 Comments »Updated January 11, 2013

As I and many others predicted, we didn’t plunge down the fiscal cliff at the end of 2012. But we’ll be back at the edge again soon, for refusing to borrow the money required to pay bills Congress has already rung up, or for threatening some extraordinarily badly designed sequestration or across-the-board cut in discretionary spending. And while I didn’t think last month that politicians would let tax rates skyrocket at the beginning of 2013, and I don’t think now that they will refuse to pay foreign lenders, Social Security recipients, or doctors, I don’t like jumping over cliffs with bungee cords attached. It’s a notoriously bad use of time and energy. Plus, I don’t trust the bungee cords.

Either way, people keep asking, why can’t these guys and gals just get together and compromise?

The main answer, I believe, goes beyond silly pledges not to raise taxes or touch anyone’s Social Security benefits. It’s the failure of both political parties to come clean on either the math or its implications, and the accompanying failure to reframe the public debate after our contentious last election.

Consider the plethora of misleading political rhetoric that both parties use in playing the blame game and asserting how they are trying to protect the middle class from bearing any burden for anything, any time, and anywhere. Almost every statement by President Obama or Speaker Boehner emphasizes how much he wants to protect 98 or 99 or 99.5 percent of us from having to pay more in taxes. That a middle-class family might have to pay a couple of thousand dollars more (the Tax Policy Center estimate of the tax increase for the median-income family if we had gone over the cliff at the end of 2012) is put forward as horrendous and unfair to those who “play by the rules.”

Wait a second! We are running deficits of about $9,000 per household a year right now. Those bills don’t disappear simply because we refuse to pay even $2,000 of them currently. We merely shove those costs to the future, mainly onto the young, some of whom are too young to vote. Convincing people that they can’t possibly afford to get by with $2,000 less when they’re running up credit card bills of $9,000 a year is simply dishonest. If we aim to borrow $2,000 less from foreigners by 2015 or 2016, for instance, it may mean that by then we also must consume $2,000 less relative to what we produce as a society, even if we “play by the rules.”

Let me be clear. Most economic analysis says that a country can’t dampen consumption too quickly without threatening economic growth. Still, the basic bind that both parties placed on themselves comes from promising so much to the middle class in terms of both high benefits and low taxes. The public fight over the fiscal cliff centered mainly on taxing the rich. But spending, mainly in unsustainable growth in health and retirement programs, remains the dominant long-term issue. Confining tax increases to a very small share of the population doesn’t exempt the middle class from dealing with those issues; to the contrary, it only increases the burden they must bear in spending cuts in lieu of the tax increases they avoided.

Neither party, however, can easily go to the middle class and say, “Look at how I protected you from paying more taxes so you can now get fewer benefits.” Each side criticizes the other for not offering much on reform of large health and retirement programs, but they know the consequences for leading. If the Republican Party presents its proposal first, it knows that Democrats will immediately claim that Republicans favor cuts in, say, Medicare over yet-further tax increases on the wealthy. If the Democratic Party presents any adjustments to eligibility or benefit levels, it risks losing a large share of its constituency and abandoning the one issue on which it has won elections for so many years. It’s not that the Democrats won’t compromise, they just want to be able to blame Republicans for whatever happens to the middle class. Similarly, it’s not that Republicans don’t want entitlement reform, they just don’t want to bear the brunt of the criticism by themselves.

To make matters even more complicated, almost all the bargaining centers only on ameliorating, not resolving, our long-term problem. This means the fight will continue for years, so each party wants to position itself for the next and then the next round of debates.

The broader issue needs to be reframed, somewhat like Erskine Bowles and Alan Simpson did, with a fuller, shared-party explanation to the public that we’re all in this together. It was too late for that at the end of 2012, and will be too late again the next time we focus our attention primarily on avoiding some precipice. But without that broader type of effort, this fight is not going away for a very long time.

Ten Questions on Cutting Back Itemized Deductions

Posted: December 11, 2012 Filed under: Columns, Nonprofits and Philanthropy, Taxes and Budget 1 Comment »- Why are itemized deductions getting so much more attention in budget negotiations than other tax breaks?

- Itemized deductions show up on tax returns, so they are among the most visible of all tax subsidies or adjustments. Other tax breaks tend to be harder for politicians and the public to understand.

- Why do most proposals to limit itemized deductions focus on higher-income taxpayers?

- Politicians run from telling the middle class that they get most government benefits, pay most government taxes, and eventually will have to get less and pay more to help get our budget under control. Meanwhile, Democrats want to increase taxes on higher-income taxpayers, but Republicans don’t want to increase tax rates. Itemized deductions for higher-income taxpayers are among the few options that fit amidst these limitations.

- How much of the revenue lost from all tax expenditures or subsidies comes from the itemized deductions being discussed?

- By one estimate, individual tax expenditures will cost the government about $1.2 trillion a year in 2015. If other policies aren’t changed, itemized deductions will cost about $180 billion by then, or about 15 percent of the total. Itemized deductions taken by those making more than $200,000 as individuals or $250,000 for couples (the president’s proposed level for starting to deny deductions) make up about 8 percent of total individual tax expenditures, or about $100 billion. See this graph on the revenue gained from various tax proposals and how this compares to the deficit.

- How many taxpayers would be affected by these limits, and how much revenue would be raised?

- Many proposals to cut back on itemized deductions affect only about 2 or 3 percent of taxpayers and would raise $15–$60 billion in 2015, compared with a deficit of close to $900 billion under current policies. A tougher cap would raise more revenue but affect more taxpayers. Obviously, a lot depends upon the actual legislation.

- Are limits on other tax expenditures being discussed?

- Yes. Some proposals would increase the tax on dividends and capital gains back to its level before the Bush-era tax cuts. Some would cap the exclusion allowed to employees buying health insurance from their employers. The president has proposed a number of other, generally smaller cutbacks, including removing tax breaks for employee contributions to 401(k) and similar retirement plans. Most of these have gotten less attention.

- What’s the appeal of across-the-board limits on itemized deductions?

- Politicians think various constituencies will less strongly oppose across-the-board limits that don’t single out any particular provision. To some supporters, these limits appear to attack interest groups even-handedly.

- But do they attack various interests even-handedly?

- No. Across-the-board limits would hit charitable deductions the hardest since people can quickly offset the tax increase by giving less to charity. State and local tax deductions, on the other hand, are less discretionary. Also, higher-income taxpayers give a large portion of all charitable contributions, so that sector is hit worse than, say, housing, where mortgage interest deductions are more concentrated in a middle class usually unaffected by the proposal.

- Do different caps affect behavior differently?

- Yes. An overall limit of $50,000 on itemized deductions effectively gives a 0 percent subsidy for, say, an extra dollar of home mortgage interest above that limit. Other proposals simply limit the subsidy to 25 cents or 28 cents but generally place no extra bounds (beyond current law) on how many dollars can be deducted.

- What are the drawbacks of overall deduction caps?

- Some deductions, just like government programs, are more justifiable than others. For instance, society may want to encourage charitable giving but not want to encourage debt to buy bigger homes or second homes. Almost all tax experts—left, right, and independent—feel that the best way to reform government programs, whether hidden in the tax code or not, is to tackle each one on its own merits.

- How does tackling a particular incentive on its own merits work?

- Consider the itemized deduction for charitable contributions. Instead of discouraging giving that might be quite desirable societally, policymakers could focus on lowering deductions for items with low compliance rates. For example, the deductions that people claim for donating used clothes seem significantly larger than the value the charities derive from such donations. Congress could also restrict subsidies for the first dollars of giving, such as the first 1 or 2 percent of income—amounts taxpayers would likely give in absence of any incentive. The incentive would then remain for the more discretionary giving above that floor. Finally, some of the revenue gained could then be spent where giving would be more responsive to the incentive. For instance, Congress could allow taxpayers to take deductions for contributions made up until they file their tax returns, or it could provide a deduction above a floor to those who currently don’t itemize.

In effect, Congress could strengthen its fiscal posture and the charitable sector at the same time. The same argument could be made for allocating homeownership subsidies better. In sum, blanket rules are arbitrary when applied to programs of different effectiveness and merit.