Measuring the “Charitability” of Hospitals: Putting Meat on the Bones of the Grassley-Hatch Request

Posted: May 25, 2018 Filed under: Uncategorized Comments Off on Measuring the “Charitability” of Hospitals: Putting Meat on the Bones of the Grassley-Hatch RequestOn February 15, 2018, Senators Chuck Grassley (R-Iowa) and Orrin Hatch (R-Utah) requested specific information from the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) on its oversight activities of nonprofit hospitals. Skeptical about whether some or many nonprofit hospitals actually operate as charities, they sought evidence that they provide “community benefits.”

To provide evidence well beyond what the IRS considers, I suggest that they and the hospitals themselves adopt a tool I developed to help assess whether a charity fully utilizes the charitable resources available to it. It turns out that a hospital can qualify for tax exemption and provide community benefits while operating more as a partnership serving its doctors, staff, and managers than as a charity. The main value of this tool, however, is not for a top-down assessment by an understaffed IRS wading through a measurement swamp, but for self-assessment of charitable operations by truly mission-driven hospitals.

This measurement tool is simply a variation on the accountant’s most powerful tools: the income statement and the balance sheet. Using this tool goes beyond the traditional balancing of cash flows in and cash flows out, or of assets with liabilities, to what I call the uses and sources of those “resources” gathered to pursue the charitable activities of the hospital. Of course, it can be used by almost all charities, not just hospitals.

READ MORE AT TAXPOLICYCENTER.ORG

How Recent Tax Reform Sounds a Clarion Call for Real Reform of Homeownership Policy

Posted: May 10, 2018 Filed under: Uncategorized Comments Off on How Recent Tax Reform Sounds a Clarion Call for Real Reform of Homeownership PolicyThis column first appeared on TaxVox.

By roughly doubling the standard deduction and limiting the deduction from federal taxable income of state and local taxes (SALT), the Tax Cut and Jobs Act of 2017 (TCJA) significantly reduced the tax benefits of homeownership, especially for middle-income households. Not only does it cap the deductibility of state and local taxes, including local property taxes, it also substantially reduces the number of taxpayers who will itemize deductions at all, including those who pay mortgage interest.

As a result, it raises important questions about the future viability of tax subsidies that primarily benefit higher-income taxpayers who own expensive, highly-leveraged homes. These changes made homeownership tax subsidies even more upside-down than pre-TCJA tax law and provide a tax incentive to further concentrate the distribution of private wealth.

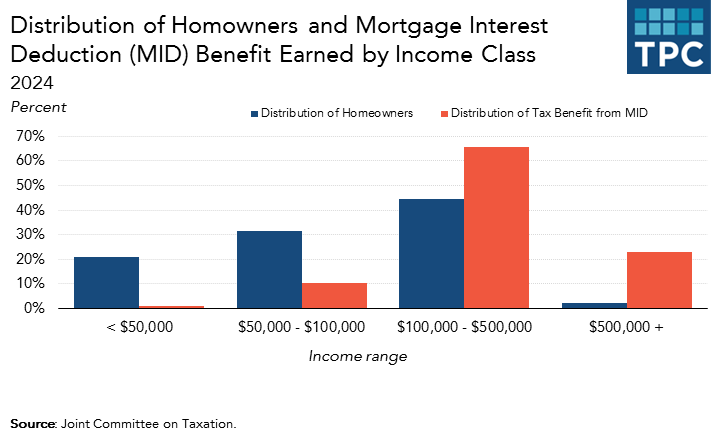

The Congressional Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) recently released projections on the future distribution of some of the tax benefits of homeownership. Out of 77 million projected homeowners in 2024, only about one-fifth will make $50,000 or less. Yet, they’ll comprise about half of all households, homeowners and nonhomeowners alike. These taxpayers with annual incomes under $50,000 will get only about 1 percent (or less than $400 million out of $40 billion) of the overall tax subsidy for home mortgage interest deductions. Meanwhile, households with more than $100,000 of income will garner almost 90 percent of the subsidy.

These estimates for the mortgage interest deductions understate the total value of tax benefits from homeownership. Property tax deductions are also skewed to the rich and the upper-middle class. At the same time, it is more beneficial to build up home equity largely tax-free than to pay income tax on the returns from money kept in a savings account. This additional incentive also benefits the haves more than the have-nots because it is proportional to the amount of equity a homeowner possesses. So those with a large amount of home equity are far better off than new, usually younger, homeowners who rely heavily on borrowing to purchase a home.

There is something of a paradox to the new tax law, however. The increase in the standard deduction, and the caps on deductions for home mortgage interest and state and local tax payments are all steps that make the overall tax system more progressive. And the reduction in tax incentives probably put a small brake on inflation in the value of housing, making it a bit more affordable for both renters and homeowners.

Still, as a matter of homeownership policy, the result is that only a little over one tenth of taxpayers—those who will still itemize after the TCJA—will have the opportunity to benefit from most tax subsidies for homeownership. And that will require advocates for extending ownership incentives to more low- and middle-income groups to make the case not simply for better distributing existing tax subsidies but for maintaining any at all. As the increase in the standard deduction shows, there are a lot of ways of promoting progressivity that do not entail subsidizing homeownership.

The case for homeownership subsidies in the tax code and elsewhere rests mainly on the following two grounds: (1) homeownership is a way of promoting better citizenship and more stable communities; and (2) homeownership helps improve wealth accumulation by nudging many who might not otherwise save to do so by paying off mortgages and making capital improvements on their houses.

The saving argument is one that does apply mainly to low- and moderate income households. Homeownership is the primary source of saving for these households, even more important than private retirement saving. If one cares about the uneven distribution of wealth, and related issues of financing retirement for moderate-income households, then encouraging wealth accumulation through housing may be an appealing strategy.

The bottom line: When it comes to homeownership, the TCJA has left the nation with an upside-down tax incentive that applies to only about one-tenth of all households—nearly all of them with high incomes.

Such a design doesn’t pass the laugh test for political sustainability. The new tax law’s crazy remnant of a homeownership tax subsidy should encourage policymakers to rethink housing policy, including tax benefits and direct spending programs for both renters and owners. Given the structure of the TCJA’s tax subsidies, the bar is relatively low for policymakers to find an improvement.

Donald Lubick: Public Servant

Posted: April 7, 2018 Filed under: Uncategorized Comments Off on Donald Lubick: Public ServantThis column first appeared on TaxVox.

The Tax Policy Center is hosting its third annual Symposium in honor of Donald C. Lubick on Monday, April 9 at the Brookings Insitution. Given the chaos that defines tax policy these days, it seems like a good time to explain why we both honor Don and desperately need more leaders like him.

Don served presidents Kennedy, Johnson, Carter, and Clinton, and served on President-elect Obama’s transition team in 2008. That’s public service over more than four decades. He also worked to improve tax policy from Buffalo, NY to Eastern Europe.

A protégé of the legendary Stanley Surrey, Don is guided by basic principles of tax policy: efficiency, simplicity, and the concept of horizontal equity–idea that that equals should be treated equally under the law.

Even though he started out as a Republican, he also believed in progressivity. Yes, Don was once a Republican. His great friend Stu Eizenstat told me that the Kennedy Administration almost didn’t hire Don. The White House asked Stan Surrey why it should give an important tax policy job to a registered Republican. The answer, of course, was that Don was talented about tax policy and that he would serve Democratic Administrations as well as any other.

The principles that are so important to Don do not always lead to exact conclusions about what policy is best, but they create important boundaries that frame policymaking.

As one of Don’s students at Treasury, I learned that while politics requires compromises, the first draft of policy should hew to those principled boundaries.

Don surely didn’t win every battle. He failed to convince President Carter to veto the 1978 tax cut that included almost no reform. And Stu recounts that the only time Don ever read congressional testimony verbatim was when he was asked to defend some energy tax credits.

When I first worked with Don, Treasury’s Office of Tax Policy played a much larger role formulating policy for both the President and Congress than it does today. Few outside the office can fully know how they benefit from Don’s work building upon the culture, ethic, and practice of that vital office.

Unfortunately, as the legislative branch reasserted control over each stage of tax policy formulation, and the White House asserted ever more control over the Treasury, decisions became more politicized much earlier in the process, losing focus on those policy foundations that are so important to Don. As we saw last year, Congress has yet to figure out how write that all-important first draft in a way that will sustain a principled basis as that tax legislation moves toward enactment.

Reflecting on that trend, Don famously quips that each of his tours at Treasury was better than the next. He repeatedly answered the call to public service, at significant financial cost. And while in private practice, he forswore the allure of the giant law firm, choosing instead firms where teamwork was more valued. He leads through vision, creates an esprit de corps among those staff with whom he works, makes debates over tax policy exciting, and easily shares credit.

All of us at TPC are pleased to honor a person of such character, whose legacy will long influence how good tax policy is made and help us recognize when it is not.

Pete Peterson and Our Chaotic National Debates

Posted: April 4, 2018 Filed under: Uncategorized Comments Off on Pete Peterson and Our Chaotic National DebatesThis column originally appeared on TaxVox.

Each person’s death gives us a moment to pause and ask what lessons their lives offer for us. Here is a lesson from the life of Peter G. (Pete) Peterson, who died on March 20, 2018 at the age of 91: We could reduce our current political chaos by shifting more political resources toward efforts to find sensible, consensus solutions to policy challenges.

Pete Peterson played large on the national stage, in business, politics, and policy. In recent years, he focused much of his energy—and his money—on the Peter G. Peterson Foundation.

Pete’s particular concern was government budgets, which is the focus of his foundation. His long-standing push for fiscal prudence has been attacked by some on both left and right, but his concerns rested on two apolitical truths: Debt cannot keep rising faster than income, and the consequences of fiscal policy go beyond budget deficits to affect issues such as how we invest in our children. He sometimes called himself the last of the Rockefeller Republicans, taking on Democrats and Republicans alike.

I worked with Pete as Vice-President of his foundation. The Urban Institute and the Tax Policy Center, where I currently work, receive research grants from his foundation. So, I am not a disinterested party when it comes to either Pete or budget policy. But Pete’s life was an example of how to engage in national debates.

Today, these debates are often dominated by partisanship and what we might call “self-interest” groups. This aspect of politics—and political money– won’t go away, but it’s way out of proportion to how we should be spending our precious resources in engaging policy issues.

Unfortunately, instead of seeking devoting a fair share of resources toward creating a rational common ground, we get sucked into supporting an escalating arms race aimed at opposing those idiots on the other side.

The large national organizations that pursue their own particular agendas–whether the NRA, AARP, Chamber of Commerce, or AFL-CIO–may represent legitimate issues. But by scaring us into believing they are preserving our very lives and liberty, and that we should be offended at any reform that asks us to give up anything, they distort reality, raise more money, and attain even more influence and power.

It is the same with electoral politics. Noncompetitive legislative districts have long elected representatives who serve the median voter in their own party, but not the district as a whole. Interest groups have long figured out how to exploit that system to further divide and conquer.

The media feeds on and amplifies the frenzy. It seeks controversy, which is not the same as seeking truth. Like moths led to a flame, our media has become easily manipulated by those who recognize that controversy creates attention; attention produces fame; and fame enhances power.

So, what does Pete have to do with all of this? None of what I have noted about the use of power is new, but the way to prevent self-interest groups from dividing us for their own objectives is simple: unite. Stop being so outspent by those groups. Instead of lavishing donations on the arms race of such interest groups and the two major political parties, do what Pete did and focus resources on efforts to create that elusive common ground for rationale dialogue.

Pete had nothing against groups with very specific policy agendas. After all, he funded several. But those groups do not focus on convincing policymakers to shift resources from other special interests for their own benefit. Rather, they argue for budget and trade policy that they believe enhance the greater good. You don’t have to agree with Pete’s priorities to recognize that he was not attempting to promote any political party’s agenda, but to support those who could compromise civilly on common objectives. It is a lesson worth remembering.

Charities Have Plenty of Opportunity to Advance Giving Despite Tax Law Losses

Posted: March 1, 2018 Filed under: Uncategorized Comments Off on Charities Have Plenty of Opportunity to Advance Giving Despite Tax Law LossesThis column originally appeared in TaxVox. A longer version of this essay was first published in the Chronicle of Philanthropy.

By substantially cutting the number of taxpayers who will receive a charitable deduction, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) has created an opportunity for charities to help redesign the tax subsidies that are so important to their fundraising. Indeed, they—and Congress—are almost compelled to do so.

After all, the TCJA’s overhaul of the individual income tax leaves only a little over one-tenth of households — mainly high-income taxpayers — eligible to deduct their charitable gifts in 2018. Because the new law significantly increases the standard deduction (to $12,000 for singles and $24,000 for couples), and trims some key itemized deductions, the vast majority of taxpayers will forego itemizing. As a result, the number of households taking the charitable deduction will fall from 37 million to 16 million.

A charitable deduction available only to the most affluent donors may not be politically sustainable. That said, nonprofits must present Congress not simply with a wish list but with alternatives that can better encourage giving without adding significantly to the rising federal budget deficit and in a way that is easily administrable by the IRS.

Non-profit organizations also must acknowledge public concerns about the way they are managed. Often, they receive only limited support from both Democratic and Republican lawmakers, who sometimes see them as just another special interest group. These same policy makers read widespread stories of abuse, including overvaluation of deductions claimed by taxpayers.

Lawmakers question whether highly-compensated executives at non-profits are as committed to their charity’s mission as its contributors. Indeed, the TCJA also imposed a new excise tax on non-profits that pay their executives $1 million or more and a new tax on investment income earned by private colleges with large financial endowments.

That said, as charities face budget cuts and the people they serve lose services, it seems easier than ever to make the case that government should renew its commitment to a strong and effective charitable sector.

A widely-available tax benefit for charitable donations could be a marvelous way to demonstrate that the US government and the public value those who help others. It could strongly reinforce and champion America’s exceptional tendency to solve problems through charitable efforts. In return for this and other reforms, nonprofits would agree that legislation should be designed around evidence as to what best encourages giving.

Here are three ways Congress could improve tax incentives for charitable giving at little or no additional loss of revenue.

First, extend the charitable deduction to everyone, but only for charitable contributions that are greater than some stated share of income. This could encourage more giving but concentrate the tax subsidy on those gifts above what people would likely give without a deduction. Such a design could not only be more cost-effective but it would limit the gifts that a resource-constrained IRS would have to monitor.

Second, let people deduct right away any gifts they make through April 15 (or before they file their tax returns) rather than keeping the current law’s December 31 deadline. This schedule, like the one the Tax Code applies to contributions to individual retirement accounts, would provide more bang per buck than almost any other charitable incentive I have examined. The House has passed such a bill in the past.

Third, improve the system charities use to report the gifts they receive to donors and to the IRS. Yes, reporting to the IRS what they usually report to individuals would mean a bit more work and expense for non-profits, but this simple step would reduce tax cheating and generate additional revenue that Congress could use to enhance tax incentives for real givers.

Of course, these efforts may go nowhere if attempts are not made to improve the image of the nonprofit world. We need a long-term and broad campaign focused on extolling examples of generosity, with less attention to specific charities or campaigns since people vary widely in the types of efforts they like to support.

The losses to charities in the new tax law are significant — a decline of about 30 percent in the federal tax subsidy for charitable giving. Yet this adversity may create an opportunity to design cost-effective tax subsidies, reduce tax non-compliance, and enhance the reputation of charities. A drive to strengthen the nation’s charitable efforts provides common ground for a nation desperately in need of reforms that unite rather than divide us.

Did the President and Congress “Give” Us a Tax Cut?

Posted: February 6, 2018 Filed under: Uncategorized Comments Off on Did the President and Congress “Give” Us a Tax Cut?This column originally appeared on TaxVox.

Politicians love to claim that they have given us something. “We want to give you, the American people, a giant tax cut for Christmas. And when I say giant, I mean giant.” So proclaimed President Trump, with words echoed by many Congressional leaders.

There were only two problems with the statement. The tax cut wasn’t giant and the President and Congress didn’t give us anything.

Not that Republicans stand alone in their claims of generosity. Democrats claimed they gave millions of Americans health insurance when they passed the 2010 Affordable Care Act.

But while Congress and the President credit themselves for giving us something, they really are transferring public resources to some of us from others. In aggregate and over time, we must pay for anything they claim to give.

I find it easiest to divide the two sides of the balance sheet required for new legislation into giveaways and takeaways. Giveaways generally come in the form of tax cuts and spending increases, takeaways in the form of spending cuts and tax increases. Just as sources of funds must equal uses of funds for the budget as a whole, so also for new legislation must the sum of new giveaways be balanced by new takeaways.

Of course, some of the takeaways can be deferred through borrowing. Politicians never count those costs when announcing the amount they claim to have given us.

In a 1976 column in the journal National Observer, entitled, “Taxes and the Two Santa Claus Theory,” conservative columnist and editor Jude Wanniski argued that Republicans needed be the party of tax cuts the way he asserted that Democrats played Santa Claus when they increased spending for social programs or passed redistributionist tax legislation.

At that time, Republicans had long been a minority party, particularly in the House of Representatives. Wanniski argued that they would never gain power as long as they simply opposed Santa-like spending increases or promoted raising taxes to pay for them.

In some ways, he got what he wanted. In the first years of the Republican presidencies of Ronald Reagan, George W. Bush, and Donald Trump, Congress passed tax cuts.

Trump’s description of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) as a Christmas gift lends full credence to the belief that political parties try to retain power by acting as Santa. What Wanniski hadn’t fully anticipated was how far we have gone toward having two Santas acting at the same time, with scheduled spending increases being matched by new tax cuts that make the whole federal fiscal system increasingly unsustainable.

I’m not arguing the relative merits of tax cuts versus new spending. Government can—and should—shift resources in ways it believes will provide a future return to society. But that is different from saying that the money is free, like a gift from Santa.

For instance, Republicans believe shifting resources to business in the form of tax cuts in the TCJA will generate an economic return just as families believe they would generate a return by shifting money to pay for their children’s education. But neither Congress nor families can claim that the transaction is free, just because the money came from additional borrowing on our public or family credit card.

While both government and personal debt tempt us to live for today, only with government debt can Santa leave an IOU for Americans not yet identified and in some cases not yet born. The two competing Santas explain better than anything why borrowing in the U.S. has increased extraordinarily in recent decades, continually rising to new all-time highs outside of a World War II peak that was scheduled to decline quickly once war spending ended.

While analysts at the Tax Policy Center and Joint Committee on Taxation can distribute specified changes in the law—for instance, who benefits from higher child tax credits—they can’t identify the future losers. Thus, the distributional tables, just like claims that our elected officials have given us something, are often incomplete and in some ways misleading. While these analysts can and do at times examine implications such as how tax cuts or spending increases might eventually be financed, those analyses get much less press attention than the explicit listing of today’s known “winners” and “losers.”

The damage to good budget policy is obvious. It will always have trouble getting traction as long as we fail to recognize that we, not the President or Congress, are the ones who pay for what they claim to give away.

The TCJA Will Create More Complexity for Taxpayers Than It Claims

Posted: January 8, 2018 Filed under: Uncategorized 1 Comment »This column originally appeared on TaxVox.

Among the most complex provisions of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) is its special tax deduction for income earned by pass-through businesses. In an attempt to prevent the new tax break from turning into an unmitigated revenue loss for the Treasury, Congress created a set of complicated “guardrails” to limit its use. Almost all tax experts agree that many businesses will need to consult tax lawyers and accountants for years to come to minimize taxes and insure compliance with the new law. Perhaps millions will change their form of ownership. Some taxpayers will also find it desirable to create multiple layers of corporations, partnerships, and other pass-through businesses, with varying degrees of ownership, to minimize their tax burden.

Yet, the official “complexity analysis” that accompanies the just-passed TCJA falls far short of telling the real story of how challenging this provision will be for many business owners.

In 1998, Congress enacted the IRS Restructuring and Reform Act that, in part, required the staff of the Joint Committee on Taxation, in consultation with the Internal Revenue Service and the Treasury Department, to provide a tax complexity analysis “for all legislation reported by the Senate Committee on Finance, the House Committee on Ways and Means, or any committee of conference.” The analysis is supposed to specify any added costs or additional recordkeeping for individuals and small businesses, as well as any need for regulatory guidance.

As required, JCT did produce such an analysis just before the House passed the TCJA and again just before Congress adopted a final bill. But because Congress produced the TCJA in less than two months, it appears that JCT, IRS, and Treasury were overwhelmed with other work and simply did not complete a proper complexity analysis. The pass-through provisions are the most striking example of this shortcoming.

Some provisions of the new law attempt to deter employees from converting themselves into a business or independent contractor to benefit from this tax break. Others attempt to separate “owners” from “employees” even when both make the same amount of money from the same partnership. Limits are placed on the deduction for income from “personal service” companies. Other limits are based on taxable income or wages paid. Meanwhile, because Congress established a corporate income tax rate that is significantly lower than the individual income tax rate, businesses must decide whether to organize specific business activities as pass-through entities or as a taxable corporation.

Here is JCT’s full analysis:

It is estimated that the provision will affect over ten percent of small business tax returns.

It is not anticipated that individuals will need to keep additional records due to the provision. It should not result in an increase in disputes with the IRS, nor will regulatory guidance be necessary to implement this provision. It may, however, increase the number of questions that taxpayers ask the IRS, such as how to calculate qualified business income and how to apply the phaseins of the W–2 wage (or W–2 wage and capital) limit and of the exclusion of service business income in the case of taxpayers with taxable income exceeding the threshold amount of $157,500 (twice that amount or $315,000 in the case of a joint return), indexed. This increased volume of questions could have an adverse impact on other elements of IRS’s operation, such as the levels of taxpayer service. The provision should not increase the tax preparation costs for most individuals. The IRS will need to add to the individual income tax forms package a new worksheet so that taxpayers can calculate their qualified business income, as well as the phaseins. This worksheet will require a series of calculations.

The analysis says the provision will affect “over ten percent of small business tax returns.” But a number between 10 percent and 100 percent is not very informative, and in any event, there are millions of small businesses.

The analysis asserts that “[i]t is not anticipated that individuals will need to keep additional records” and “[i]t should not result in an increase in disputes with the IRS nor will regulatory guidance be necessary.” This seems implausible at best given the obvious potential for gaming this provision.

The analysis’s claim that “[t]he provision should not increase the tax preparation costs for most individuals” is downright misleading. Since most individuals are not business owners, it is self-evident that their costs won’t increase due to this provision. But the real question, which the analysis does not answer, is what about those individuals who are business owners—or employees who can convert to being business owners as independent contractors? Almost surely, the increased record-keeping alone should increase costs.

Perhaps most importantly, the analysis is silent on the required planning “costs to taxpayers” that nearly always exceed those associated with filing tax returns.

As a former Treasury official, I greatly respect those nonpartisan offices that serve the public so well, such as the JCT and the Treasury’s Office of Tax Policy. I once dedicated a book to IRS personnel, who do the thankless task of reducing the share of the taxes borne by honest taxpayers. So, I do not make this criticism of their work product lightly.

In the case of the complexity analysis of the TCJA, these agencies have more work to do to fulfill the spirit of the law, not just its letter. More important, Congress needs to legislate in a way that allows staff to fulfill the 1998 statutory mandate.

Thanks to Robert Pear of The New York Times, who first asked me about the House bill’s complexity analysis.

Ten Wishes for the New Year

Posted: January 4, 2018 Filed under: Uncategorized 1 Comment »I wish…

- that presidents, Cabinet members, legislators, and other elected officials would be held to the same ethical standards and penalties for wrong-doing as entry-level civil servants;

- that Congress would attack sycophancy directly by slashing the number of political appointees and the larger number of would-be appointees who view it as the route to power;

- that the media would examine how its pursuit of stories with sensationalism and conflict has been exploited by terrorists and unethical politicians alike to garner attention and power;

- that news shows would recognize that interviewing paired Democrat and Republican spokespeople leaves out the plurality of people whose expertise, not political leanings, drives what they say;

- that more voters would stop equating so much of their personal identity with some political party banner so they would find it easier to object strongly to the wrongful actions of those for whom they voted;

- that laws would be written to penalize more the individuals who are ultimately responsible for corporate misbehavior and less the consumers and workers who often bear the costs;

- that churches claiming to prioritize the poor would come to recognize the symbolism of keeping the poor box at the back of the church and passing a collection plate for the poor only after passing one for themselves;

- that athletes signing lucrative contracts would start negotiating over money for community and public purposes rather than just themselves;

- that charities would unify around promoting the good and addressing the bad in their midst; and

- that everyone of goodwill would take heart by recognizing how important you are for bringing order out of disorder, peace amid conflict, and, for me, a continuing sense of thankfulness and hope.